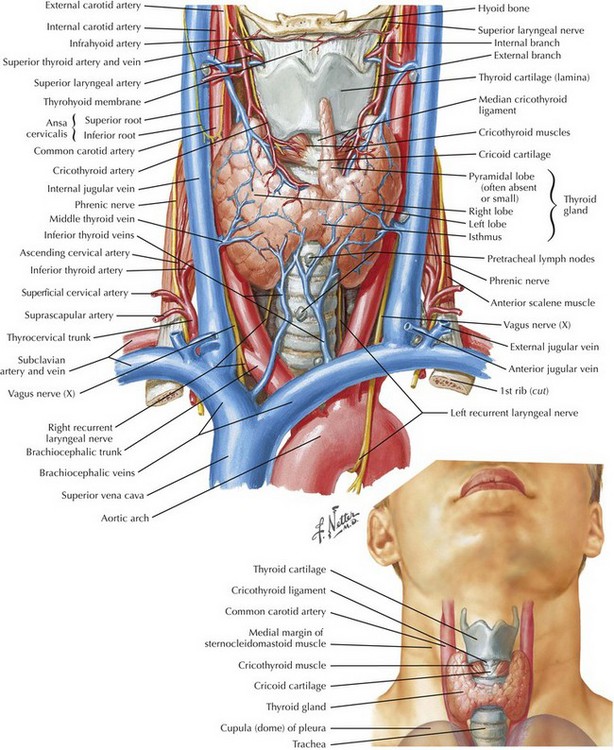

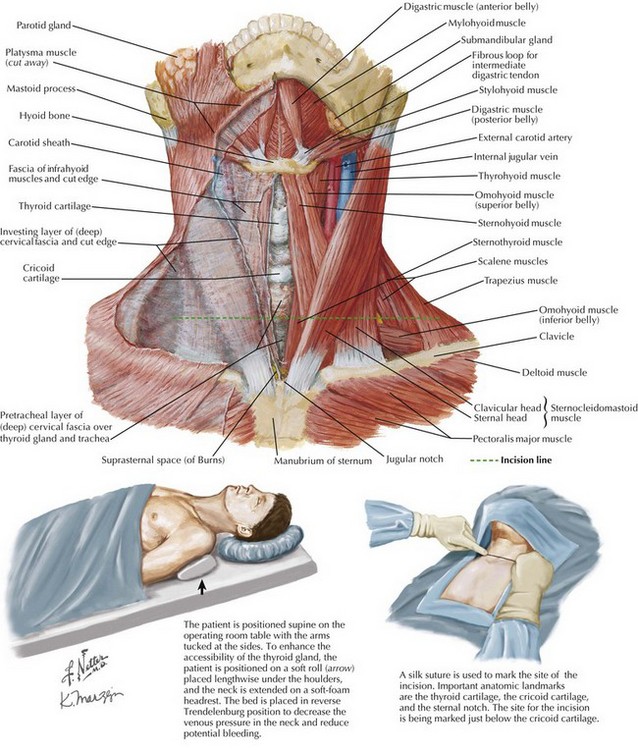

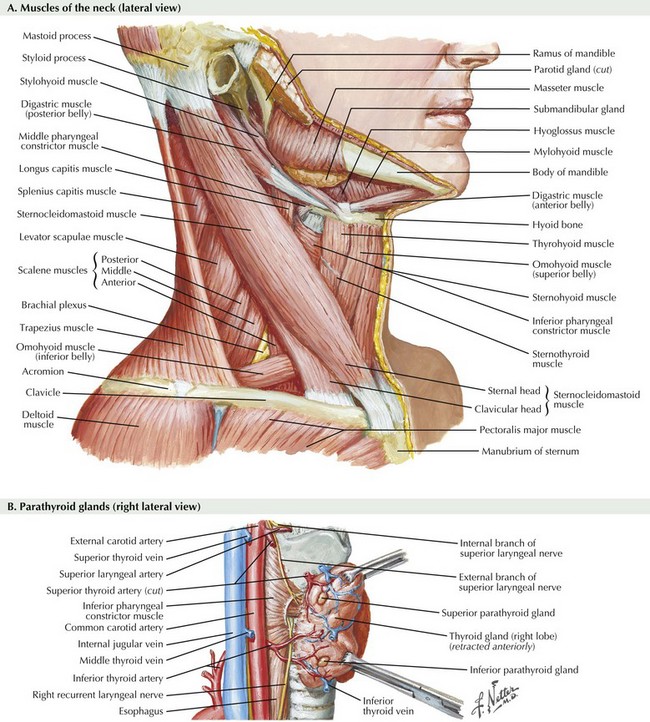

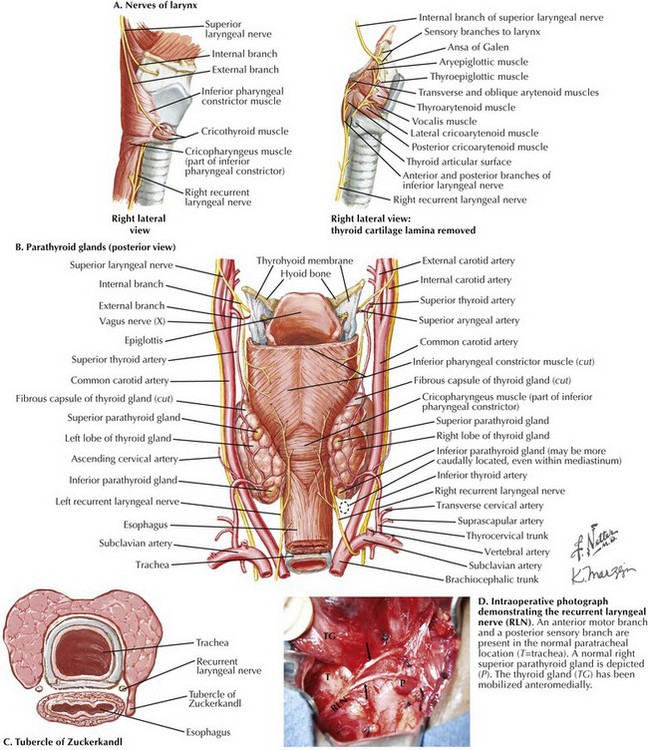

Chapter 3 The thyroid gland consists of two lobes and an isthmus (Fig. 3-1). Between 30% and 60% of patients also have a pyramidal lobe that forms as a result of the persistence of the embryologic thyroglossal duct. The principal blood supply to the thyroid gland comes from the inferior thyroid artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk and the superior thyroid artery, which is the first branch of the external carotid artery. The venous drainage of the thyroid gland is from the superior and middle thyroid veins, which empty into the internal jugular vein, and the inferior thyroid veins, which empty into the brachiocephalic veins. Determining the surface anatomy of the neck is necessary for proper placement of the skin incision (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2). The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table with the arms tucked at the side, a soft roll placed lengthwise beneath the shoulders, and the head in a soft-foam headrest with the neck extended (Fig. 3-2). Important landmarks that should be palpated include the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, the cricoid cartilage, and the sternal notch. The isthmus of the thyroid gland lies immediately below the cricoid cartilage. A transverse skin incision is made in a normal skin crease below the cricoid cartilage for an optimal cosmetic result. It is necessary to create a working space to remove the thyroid gland. This is accomplished first by dividing the subcutaneous tissue and platysma muscle to expose the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscles laterally and the sternothyroid muscles in the midline of the incision (Figs. 3-2 and 3-3, A). Superior and inferior skin flaps are raised in the subplatysmal plane, anterior to the anterior jugular veins. The skin flaps are raised superior to the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, inferior to the sternal notch, and lateral to the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Anteromedial traction is applied to the lobe of the thyroid gland, and the middle thyroid vein is divided (Fig. 3-3, B). The areolar tissue between the thyroid gland and the common carotid artery is separated using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, allowing for further anteromedial mobilization of the thyroid gland. The superior thyroid artery and the superior thyroid veins are exposed by applying caudal and lateral traction to the thyroid parenchyma at the superior pole. This helps expose the cricothyroid space and facilitates the individual ligation of the superior-pole vessels close to the thyroid gland, staying lateral to the muscles of the pharynx and the larynx to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (EBSLN). The superior laryngeal nerve is a branch of the vagus nerve from high in the neck (Fig. 3-4, A and B). At 2 to 3 cm above the superior-pole vessels, the superior laryngeal nerve divides into an internal branch that provides sensory innervations to the supraglottic area of the larynx and the base of the tongue and an external branch that provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle.

Thyroidectomy and Parathyroidectomy

Thyroidectomy

Surgical Anatomy for Thyroidectomy

Anatomy for Exposing the Thyroid Gland

Anatomy for Mobilization of the Thyroid Lobe

Anatomy of the Superior Laryngeal Nerve

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thyroidectomy and Parathyroidectomy