CHAPTER

61

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The modern addiction therapeutic community (TC) is a powerful therapeutic tool that, over the past several decades, has helped hundreds of thousands of addicts and alcoholics achieve abstinence-based recovery (1). Abstinence rates of more than 90% for many years after treatment are documented in well-established TCs.

Historically, the TC has been used to treat a variety of problems in living, but the modern addiction TC or “concept TC” is a hybrid of self-help and public support geared toward the treatment of addictive and co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

The philosophic foundation of the modern TC is personal responsibility for one’s behavior and the belief that change is fully possible if the individual exerts the personal effort to follow the teachings of the program.

Evolving out of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in the 1960s, the modern addiction TC still retains many of the underpinnings of the 12-step approach to treatment. At the same time, treatment approaches are not one-size-fits-all, and ongoing discussions around recovery models include well-documented criticisms of aa. Drug addiction is viewed as a “whole person” disorder and, therefore, is treated with a holistic approach. Emotions and feelings are considered important and can be explored in depth, but change is based on action. That action is the responsibility of the individual. As in the 12-step recovery, the individual is not expected to walk this road alone. The community is available to help the addict at every step of the way.

In the TC philosophy, drug or alcohol use is considered a symptom of a complex disorder involving the whole person. Self-destructive and defeating patterns of behavior and thought processes are thought to disrupt both the individual’s lifestyle and society’s functioning. Though genetic, environmental, and pharmacologic contributions to addiction are recognized, the individual is held fully responsible for his or her own disorder, behavior, and recovery. Addiction is regarded as the symptom, rather than the disorder. The problem is the behavior of the person, not the drug.

HISTORY AND EVOLUTION

The modern TC is a new application of an ancient concept. The Dead Sea Scrolls found at Qumron document the first TC. The communal practices of an ascetic religious sect, perhaps the Essenes, include the “Rules of Community.” The Essene code denounces “the ways of the spirit of falsehood” and speaks of the problems of greed, lying, cruelty, brazen insolence, lust, and “walking the ways of darkness and guile.” Righteous and healthy living required strict adherence to the rules and teachings of the community.

Violation of the Rules of Community incurred sanctions resembling, though much harsher than, the sanctions used in the modern addiction TC. For violations, such as lying, bearing a grudge, foolish speech or laughter, sleeping during a community meeting, or leaving a community meeting, sanctions could include periods of banishment from the community or limited rations or privileges.

At about the time Jesus walked the earth, a group of healers (therapeutrides) of the “incurable” diseases of the soul lived in Alexandria, Egypt. Philo Judaeus (25 BC to 45 AD) described the group as professing “an art of medicine for [excessive] pleasures and appetites … the immeasurable multitude of passions and vices” (2). As in the modern TC philosophy, diseases of the soul were seen as manifesting themselves through the whole person. Healing was regarded as occurring through some form of community involvement.

The Washingtonians (founded by a group of drinkers) later appeared in the United States as a 19th century precursor to AA. Though the Washingtonians did not survive as a group, several of their methods are still apparent in the modern addiction TC. These include the commitment to abstinence, proselytizing its message to others, and the practice of self-appraisal during group meetings.

The conceptual and organizational lineage of the modern addiction TC began about 1921 with the Oxford Group—also known as The Buchmanites, the First Century Christians Fellowship, and Moral Rearmament (3). A branch of the Oxford Group in Akron, OH, evolved into AA in 1935 under the guidance of Bill Wilson and Doctor Bob Smith. A Santa Monica, CA, AA group evolved into Synanon in 1958 under the guidance of AA members. From Synanon sprang Daytop Village in New York City, under the guidance of Monsignor William O’Brien. From Daytop, more than 100 other therapeutic communities have developed around the world.

The Oxford Group (or Oxford Movement) began in the second decade of the 20th century as the First Century Christian Fellowship. Founded by the Lutheran evangelist minister Frank Buchman, the early Oxford Group preached a return to the purity and innocence of the early church. This spiritual rebirth was to be applied to all forms of human suffering. Though alcoholism and mental illness were not the primary focus of the Oxford Group, they were certainly seen as signs of spiritual deficit and thus were encompassed by the Oxford Group’s principles.

The Reverend Buchman headquartered the Oxford Movement in New York City, where Dr. Samuel Shoemaker, a pastor of Calvary Episcopal Church, became involved as well. During this period, the philosophies of the Quakers and Anabaptists (precursors to the Mennonites and Amish) began to influence the movement. These early influences carry through to the foundation of the modern addiction TC. Concepts and practices such as the work ethic, mutual concern, and sharing guidance are basic to the TC philosophy. Evangelical values such as honesty, purity, unselfishness, love, making amends for harm done, and working well with others all can be traced to this era (4,5).

The thread continues even today. Though not directly related to the Oxford Group, “Oxford House” is the name of a self-run, self-supported sober-living housing initiative that was begun in Silver Spring, MD, in 1975 and now includes more than 450 sober-living houses situated throughout the United States.

The 12 steps of AA evolved directly from the 6 steps of the Oxford Group. Together with the Twelve Traditions and the Twelve Concepts, the 12 steps embody the principles that guide the individual in recovery. The concepts of confessing to others and making amends and the belief that the individual change requires conversion to belief in the group are principles derived directly from the Oxford Group. Other AA principles include admitting one’s loss of control over alcohol and surrendering to one’s “Higher Power,” performing self-examination, seeking help from one’s Higher Power in changing one’s self, making amends to others, praying in the personal struggle, and helping others to engage in a similar process. Some striking differences are found, however. AA deviated from the Oxford requirement of a religious God by allowing each AA member to develop his or her own concept of a Higher Power. Though AA does not require a Christian god, its principles do stress that one’s power to change is derived from a power greater than one’s self. Nonsectarian AA, in fact, allows the Higher Power to be the AA group. This concept of the group as Higher Power is further developed in Synanon and later TCs, as it evolved into reliance on self and group process as the medium of individual behavioral change.

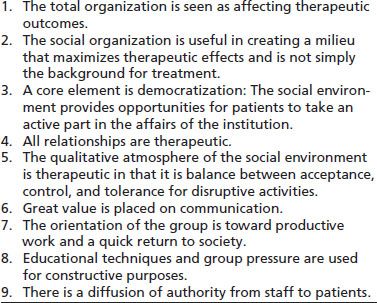

Fifteen years before Synanon appeared on the scene in the United States, however, psychiatric hospital TCs began to develop in Great Britain. Pioneered by Maxwell Jones, the first of these appeared as a social rehabilitation unit at Belmont Hospital in England in the mid-1940s. The Jones TC embraced the therapeutic nature of the total environment as a treatment tool (Table 61-1). Though the Jones TC is used today as a viable treatment method in Great Britain, its application to the treatment of addictive disorders occurred only in the context of dual-diagnosis patients. Some addictive disorder treatment adaptation of the Jones TC model has occurred in the United States in the Veterans Administration hospitals. There are little data about the efficacy of treatment in this application.

TABLE 61-1 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PSYCHIATRIC (JONES) TC

Adapted from DeLeon G. The therapeutic community: theory, model, and method. New York, NY: Springer Publishing, 2000.

The evolution of Synanon from an AA group resulted in the concepts, program model, and basic practices that have become the essential elements of all modern addiction TCs. Synanon’s charismatic founder, Chuck Dederich, integrated his AA experiences with other philosophic, pragmatic, and psychological influences to create the Synanon program. The unique encounter group process (“the game”) evolved from weekly AA meetings. Distinct psychological changes were evident as a result of this process. The participants recognized this change as a new form of therapy and, within a year, the weekly meetings expanded into a residential community. In August 1959, the organization was officially founded to treat any addict, regardless of the chemical of choice. The name Synanon apparently was coined during the confused mumbling of a heroin addict who was having trouble pronouncing the word “seminar,” fusing it with the word “symposium.” Despite its role in the evolution of the modern TC, Synanon never considered itself a TC but rather an alternative community for teaching and living.

Synanon evolved from AA, and, as a result, the precepts of AA are fundamental to Synanon and to all modern addiction TCs. Still, the evolution did occur, and the differences are what created the TC as a distinct approach. Self-help recovery, a belief that the ability to change and heal lies within the individual and a belief that healing occurs as a result of a therapeutic relationship with others who have a similar affliction, all are philosophies common to both programs. The AA traditions and program activities led directly to the TC’s individual self-reliance, organizational self-reliance, and its schedule of regular groups and meetings.

The numbering system of AA’s 12 steps did not carry through to Synanon, but the same stages of recovery are very much a part of the Synanon program and the other modern addiction TCs as well. Steps 1 to 3 are embodied in the TC’s early-phase recovery, which emphasizes breaking through denial and engaging in the change process. Steps 4 to 9 are seen in the mid-phase recovery period of intense self-examination and socialization. This period involves taking a personal inventory, sharing confession with another person, and making amends. Steps 10 to 12 are reflected in the maturational process and increased autonomy that develop in the reentry phase of the TC. This phase requires continued personal honesty, humbly asking for help to sustain recovery, and actively helping others.

Critical differences, however, define the addiction TC as a new treatment modality. These include the residential setting, organizational structure, and profile of participants, goals, philosophy, and ideologic orientation.

Initially, residents could graduate from Synanon. Soon, however, Synanon (like AA) abandoned the concepts of graduation or completion of the program. In AA, when participants are fully integrated in society, they continue to participate in the program of recovery and continue to attend group meetings. This participation is analogous, perhaps, to continuing to attend church. In the case of 24-hour-a-day residential Synanon, completion of the program signified quite a different situation. All activities of a person’s life were to occur within the highly structured hierarchical organization, with no sort of reentry or reintegration back into society as a whole. Synanon embraced AA’s Seventh Tradition of fiscal independence with entrepreneurial spirit, developing profit-making businesses as well as pursuing both public and private funding. Though any member could rise within the hierarchy, the management was never democratic but rather oligarchic.

THE DAYTOP MODEL

Monsignor William O’Brien, a young priest, and Dr. Daniel Casriel, a Manhattan psychiatrist, first attempted to apply the concept of a TC specifically to the treatment of drug addiction. With the help of Joseph Shelly, chief probation officer of Brooklyn, NY, and Alexander Basson, a doctoral student who wrote the first grant, funds were obtained from the National Institute on Mental Health to develop an addiction TC.

The new program needed a director, and none of the initial applicants had been willing to take the job. So, Basson called the New York office of AA. A gentleman with no experience in treating drug addiction named Dean Colcord was sent to apply and was hired as the first director of Daytop Lodge (later to become Daytop Village).

Daytop Lodge opened with 25 beds on September 1, 1963, in Staten Island, NY. Dean Colcord had spent 3 weeks visiting the Westport Synanon to learn how it operated. Daytop applied the Synanon program with a strong dose of AA to the public sector treatment of addiction.

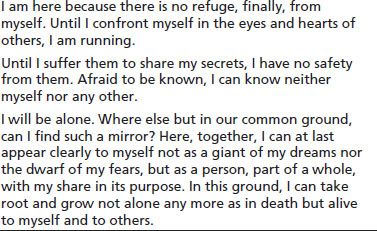

The founding of Daytop marked a milestone in the development of the modern TC (Table 61-2).

TABLE 61-2 THE DAYTOP PHILOSOPHY

Author: Richard Beauvais.

Adapted from DeLeon G. The therapeutic community: theory, model, and method. New York, NY: Springer Publishing, 2000.

The modern TC rests on a foundation of secular ideology with certain existential assumptions, including the following:

■ Self-determination: A core value is self-determination. Each individual is seen as the captain of his or her own ship and the one who determines the path of his or her life.

■ Individual responsibility: The TC philosophy holds each individual fully responsible for his or her own behavior. No matter the genetic predisposition or environmental or family influences, each person is seen as fully and completely responsible for his or her own behavior.

■ Self-change: The concept of self-change is regarded as possible through personal commitment and adherence to recovery teachings.

FEATURES OF THE MODERN THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

The addiction TC is a powerful tool for changing behavior, and its efficacy is well documented in the literature. It is less clear how and why this therapeutic modality is so effective in changing difficult behaviors for which so many other methods are not successful.

Components of a Therapeutic Community Program

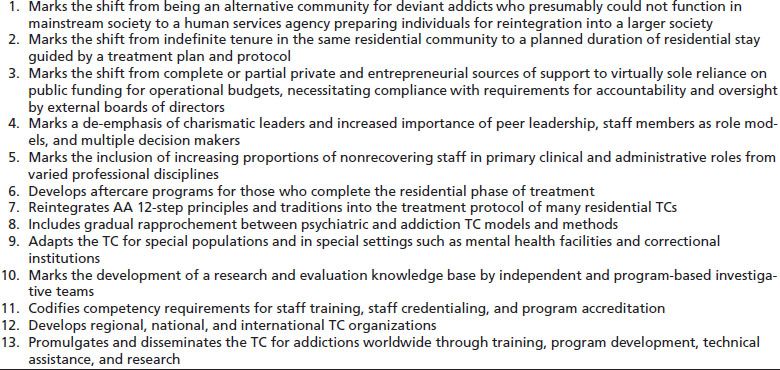

George DeLeon, PhD has written the seminal text on the TC, The Therapeutic Community: Theory, Model and Method (2000). Much of the following material has been adapted from the writings of George DeLeon and from the author’s own experience. Several features characterize TC programs that follow the Daytop Village model and other first-generation TCs (6) (Table 61-3). Although the components of the modern therapeutic community are described separately for educational purposes, it is important to emphasize that the therapeutic community is more than the sum of its component parts. While individual parts can be identified, in the spirit of community, those parts lend each other a synergy. It is their union and that synergy that creates community and gives the therapeutic community its powerful healing potential.

TABLE 61-3 FUNDAMENTAL CHANGES IN TCs AFTER THE FOUNDING OF DAYTOP VILLAGE

Adapted from DeLeon G. The therapeutic community: theory, model, and method . New York, NY: Springer Publishing, 2000.

Community Separateness

TC-oriented programs have their own identities and are housed in a space or locale that is separated from other agency or institutional programs or units or generally from the drug-related environment. In residential settings, clients remain away from outside influences 24 hours a day for several months before earning the privilege of a brief visit to the outside community. In nonresidential “day treatment” settings, the individual spends 4 to 8 hours a day in the TC environment and is monitored by peers and family while outside the TC. Even in the least restrictive outpatient settings, TC-oriented programs and components are in place. This is designed to help members gradually detach from old networks and relate to the drug-free peers in the program.

A Community Environment

The TC environment prominently features communal spaces and collective activities. Walls carry signs declaring the philosophy of the program, the messages of right living, and recovery. Cork boards and blackboards are used to identify all participants by name, seniority level, and job function in the program. Daily schedules are posted as well. These visuals display an organizational picture of the program that the individual can relate to and comprehend, thus promoting program affiliation.

Community Activities

The TC philosophy holds that, to be effective, treatment and educational services must be provided within a context of the peer community. Thus, with the exception of individual counseling, all activities are programmed in collective formats. These activities include at least one daily meal prepared, served, and shared by all members; a daily schedule of groups, meetings, and seminars; jobs performed in teams; organized recreational/leisure time; and ceremonies and rituals (to mark birthdays, phase/progress graduations, and the like).

Staff Rules and Functions

Staff members are a mix of self-help professionals who are themselves in recovery and other helping professionals (medical, legal, mental health, and educational), who are integrated through cross-training grounded in the TC perspective and community approach. Professional skills define the function of staff members (e.g., nurse, physician, lawyer, teacher, administrator, case worker, clinical counselor). Regardless of professional discipline or function, however, the generic role of all staff members is that of community members who, rather than providers and treaters, are viewed as rational authorities, facilitators, and guides in the self-help community method.

Peers as Role Models

Members who demonstrate the expected behaviors and reflect the values and teachings of the community are viewed as role models. Indeed, the strength of the community as a context for social learning relates to the number and quality of its role models. All members of the community are expected to be role models: roommates; older and younger residents; and junior, senior, and directorial staff. TCs require these multiple role models to maintain the integrity of the community and to ensure the spread of social learning effects.

A Structured Day

The structure of the program relates to the TC perspective, particularly the view of the client and recovery. Ordered activities conducted in a regular routine counter the characteristically disordered lives in which clients have lived and distract from negative thinking and boredom—factors that are thought to predispose individuals to drug use. Structured activities also are regarded as facilitating the acquisition of self-structure on the part of the individual, as expressed in time management; planning, setting, and meeting goals; and general accountability. Thus, regardless of its length, the day has a formal schedule of therapeutic and educational activities with prescribed formats, fixed times, and routine procedures.

Work as Therapy and Education

Consistent with the TC’s self-help approach, all clients are responsible for the daily management of the facility (e.g., cleaning, meal preparation and service, maintenance, purchasing, security, scheduling, preparation for group meetings, seminars, activities). In the TC, the various work roles mediate essential educational and therapeutic effects. Job functions strengthen affiliation with the program through participation, provide opportunities for skill development, and foster self-examination and personal growth through performance challenge and program responsibility. The scope and depth of clients’ work depends on the program (e.g., institutional vs. free-standing facility) and client resources (levels of psychological function, social and life skills).

Phase Format

The treatment protocol, or plan of therapeutic and educational activities, is organized into phases that reflect a developmental view of the change process. Emphasis is placed on incremental learning at each phase, so as to move the individual to the next stage of recovery.

Therapeutic Community Concepts

Formal and informal curricula are focused on teaching the TC perspective, particularly its self-help recovery concepts and view of right living. The concepts, messages, and lessons are repeated in the various groups, meetings, seminars, and peer conversations, as well as in readings, signs, and personal writings.

Peer Encounter Groups

The principal community or therapeutic group is the encounter, though other forms of therapeutic, educational, and support groups are employed as needed. The minimal objective of the peer encounter is similar to TC-oriented programs—to heighten the individual’s awareness of specific attitudes or behavior patterns that need to be modified. However, the encounter process can differ in degree of staff direction and intensity, depending on the client subgroups (e.g., adolescents, prison inmates, and the dually diagnosed).

Awareness Training

All therapeutic and educational interventions involve raising the individual’s awareness of the effects of his or her conduct and attitudes on himself or herself and the social environment and, conversely, the effect of the behaviors and attitudes of others on the individual and his or her environment.

Emotional Growth Training

Achieving the goals of personal growth and socialization involves teaching individuals how to identify feelings, express them appropriately, and manage them constructively through the interpersonal and social demands of communal life.

Planned Duration of Treatment

The optimal length of a full program involvement must be consistent with the TC goals of recovery and its developmental view of the change process. How long the individual must be involved in the program depends on his or her phase of recovery, though a minimum period of intensive involvement is required to assure internalization of the TC teachings. The duration of treatment of the traditional therapeutic community generally is 12 to 18 months. Despite the established therapeutic success and cost-effectiveness of TCs at these durations of treatment, financial and bureaucratic pressures have forced TCs to attempt to progressively shorten their treatment stays. Initially, this appeared to be successful. But as treatment stays became shorter and shorter, it became more and more difficult to maintain the earlier rates of treatment success. While every treatment modality must be cost-effective in this day and age, there appears to be no doubt that when shortened beyond a certain point, the therapeutic benefit of the TC drops off dramatically (35).

Recent Emphasis of Building Early Retention

To some extent, the traditional TC model relies on the individual to come with some level of inherent motivation. Outside factors such as family pressure, probation, parole, and financial factors may contribute to this motivation. Absent these sorts of factors, however, the TC must help the individual to develop the motivation to change if treatment is to be successful. Increasingly, the process of engagement has become a key component of treatment.

Continuity of Care

Completion of primary treatment is a stage in the recovery process. It is followed by aftercare services, which are an essential component of the TC model. Whether implemented within the main program or separately (as in residential or nonresidential halfway houses or ambulatory settings), the perspective and approach guiding aftercare programming must be continuous with that primary treatment in the TC. Thus, the views of right living and self-help recovery and the use of a peer network are essential to enhance the appropriate use of vocational, educational, mental health, social, and other typical aftercare or reentry services.

Increasingly, facilitating involvement in 12-step programs has become popular, as well as long-term monitoring and support for former clients who have fully reentered the community. Some TCs offer varying levels of case management to help former clients in negotiating with community agencies and organizations.

Using the Community as the Therapeutic Method

At first blush, the therapeutic community appears to have much in common with other forms of residential treatment. Unique to the TC, however, is the fact that the community itself is the method by which the entire individual is treated.

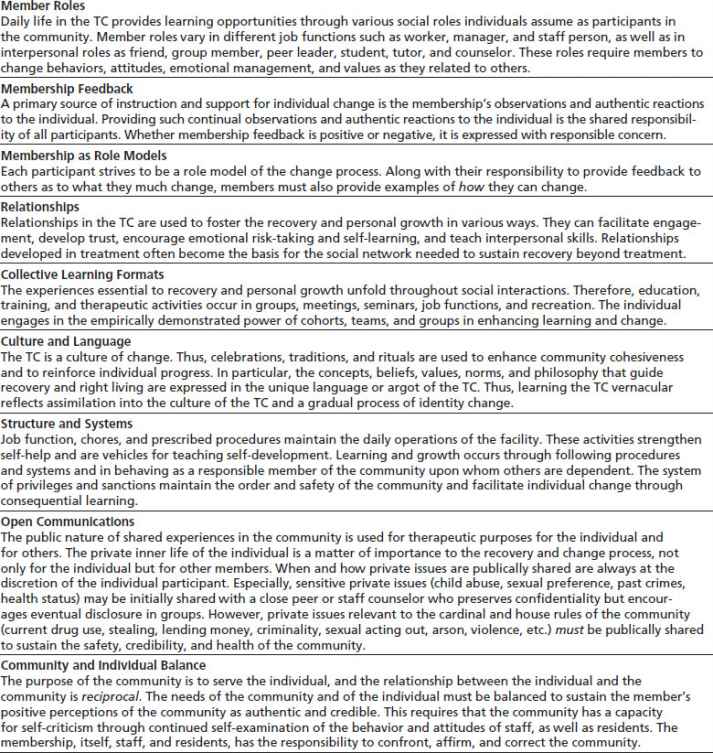

DeLeon (4) describes method as all of the “activities, strategies, materials, procedures, and techniques” that are called into play to create the desired change in the individual in treatment. As the individual participates in the TC, the elements or basic components (Table 61-4) of the method become incorporated into the individual as the tools of therapeutic change. These basic components include member roles, membership feedback, membership as role models, relationships, collective learning formats, culture and language, structure and systems, open communications, and community and individual balance.

TABLE 61-4 COMMUNITY AS CONTEXT: BASIC ELEMENTS

Data from Barr H. Outcome of drug abuse treatment on two modalities. In: DeLeon G, Ziegenfuss JI, eds. Therapeutic communities for addictions. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1986:97–108.

The European Experience: Expecting More Than the TC Can Give?

The success and therapeutic power of the TC model have not been lost on the international community. Literally hundreds of culturally appropriate TCs are scattered across the globe. The European experience, however, is worth examining.

As the success of the TC in Europe became recognized, governments began to place broader demands upon the TC model. Required staffing evolved from relatively inexpensive TC trained former addicts to much more expensive licensed counseling professionals and medical personnel the costs began to skyrocket. Over time, more challenging clientele with more serious mental, psychological, and medical problems were expected to be successfully treated in TCs that were even more restricted in their duration of treatment. Government requirements began to supersede the administrative and therapeutic decisions of the knowledgeable TC professionals, and treatment costs soon became unsustainable, finally resulting in the abandonment of the TC model in several European countries in favor of weaker but cheaper treatment alternatives (17). Unfortunately, trends in the United States appear to be following a similar pattern.

REFERRAL CRITERIA

For the physician in office-based practice, either as an addiction medicine specialist or simply as a perceptive, caring physician willing to address patients’ addictive disorders, a question often arises as to which type of treatment is most appropriate for a particular patient. This question may not be easy to answer but may well be the critical step that makes the difference between life and death for that particular human being.

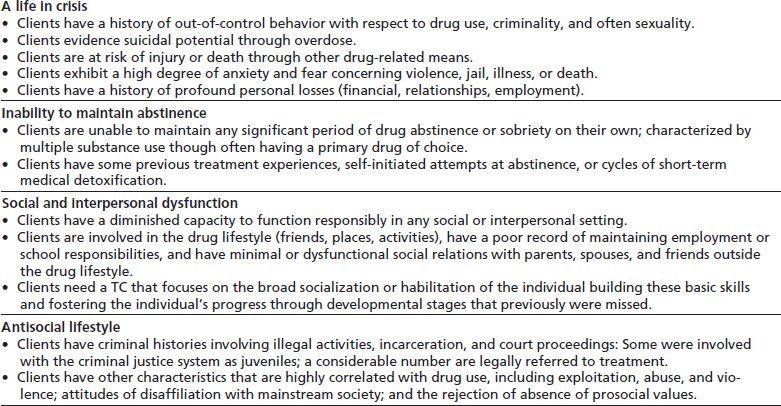

Any one of four specific characteristics would qualify an addict and/or alcoholic for treatment in a TC (Table 61-5). But just what does such a person look like? Though a complete answer to this question could fill a volume or more, a few examples may serve to illustrate the broad outlines of the characteristics that might define a patient as a good candidate for treatment in a therapeutic community.

TABLE 61-5 INDICATORS OF THE PRESENTING DISORDER AMONG TYPICAL TC CLIENTS

Adapted from Barr H. Outcome of drug abuse treatment on two modalities. In: DeLeon G, Ziegenfuss JI, eds. Therapeutic communities for addictions. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1986:97–108.

Case 1

The first example involves a patient who is abusing drugs or alcohol and who has begun to experience negative consequences of those behaviors but still is able to stop such use when the negative consequences are pointed out. For example, a young woman drinks only two or three times a year but has three wine coolers at the office Christmas party and perhaps even a joint offered by a coworker. If stopped for driving under the influence, such an individual may seek help for the problem, either on her own initiative or through a referral from the courts. Such an individual may not in fact be addicted to alcohol or drugs and probably can stop drinking and using on her own if she understands that negative consequences are directly and causally related to her substance use. She certainly does not need to participate in a long-term residential treatment program such as a TC.

Case 2

Another case involves a 44-year-old engineer who began drinking in college and has continued to drink heavily throughout his adult life. His family life may be stressed, but he still is married. His children are adolescents and not home very much. He may have had a DUI arrest 10 years earlier and, as a result, attended AA meetings briefly. But he found that he could not tolerate all the talk about God and Higher Power, so he drifted away from the meetings and continued to drink.

He was regarded as someone with high potential at the time he finished engineering school 20 years earlier, but he has not lived up to those expectations. He is resentful of his employer for not promoting him as he feels he deserves. His employer, on the other hand, is on the verge of firing him because he seems to have trouble making it to work on Mondays, especially after long weekends. He drinks six to eight vodka martinis every day when he gets home from work. However, he generally does not drink in the morning, except on the weekend. He does not consider himself an alcoholic.

Outpatient treatment probably will not be effective for this patient. He already has been to AA and found that it did not apply to his situation. If he is even slightly ready to change, he probably can do very well in hospital-based detoxification followed by inpatient rehabilitation for 30 days or so. This detoxification should be followed by outpatient treatment in either a partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient treatment program, with perhaps the additional support of a sober-living home. Finally, gradual transition back to his own home and work responsibilities over several weeks would give this fellow a good chance to build a strong foundation for a program of recovery that can well last him for the rest of his life.

Again, though his life is beginning to fall apart at the seams, this individual still has a lot going for him. He has a house, family, job, finances, and probably some social life left intact. The rest can be repaired or resurrected simply by adding some consistent sobriety to the equation.

Case 3

A third example is a 27-year-old Puerto Rican male from Spanish Harlem in New York City who began using intravenous heroin at age 14. He was raised by his mother who is also a heroin addict. He has never met his father. He began using drugs at 9 when he began to associate with the local street gang and quickly advanced to snorting and later injecting heroin. He has been incarcerated multiple times and has been infected with hepatitis B and C. He is not HIV positive at this time. When he is not in jail, he currently lives with his common law wife and three children but does not work and provides little support for the family. He spends most of his time hustling for money on the street, and his lifestyle is heavily involved with illegal and sometimes violent activity.

This client would be a great candidate for TC treatment. Treatment mandated by the criminal justice system through probation or parole would be ideal to help provide the motivation necessary to help him achieve sobriety. In addition, he needs a chance to get away from the toxic environment in which he is enmeshed and an opportunity to regain some level of physically healthy living. While the socioeconomic cards may be stacked against him, he still has a reasonable chance at achieving long-term recovery and rebuilding his life. Those around him may benefit from his recovery as well. The potential societal and family benefits of his successful recovery cannot be overemphasized.

Case 4

A fourth patient is a 34-year-old dentist who began drinking in high school and smoked a little marijuana as well. He did well in college without working very hard but found that it was easier to study if he used cocaine occasionally for those all-nighters at final exam time. After finishing dental school, he took over his father’s dental practice and did well for a few years. After a skiing injury to his back, he began taking prescription Vicodin and later OxyContin for the pain. He has had three surgeries on his back but still has pain.

The state physician diversion program interceded after he was investigated for writing excessive prescriptions for narcotics in the name of his office manager, and he currently is in the state’s physician diversion program. He has completed three inpatient treatment programs. The first program was a 1-week detoxification program with outpatient follow-up. That program proved to be barely a bump in the road of the progression of his disease. The second program consisted of inpatient detoxification followed by 4 weeks of inpatient rehabilitation in the standard 12-step format. Finally, after urinalysis showed continued opioid use, his license was suspended, and he was referred to a 90-day modified TC (MTC) program that specializes in treating professionals.

He completed the program and did well for 6 months after treatment. Then, he began to use heroin intravenously, and again was found out through random urine testing. At this point, his wife and children have left him, and he is in the throes of a divorce. He no longer has health insurance, and his car has been repossessed. He is living in an apartment that his father has been paying for from his retirement income. The diversion program is about to revoke his license and discharge him from the program for failure to derive benefit from treatment. This person is an excellent candidate for a residential modern addiction TC. He is at high risk of death. He probably has hepatitis B and C and can contract acquired immunodeficiency syndrome if he continues in his current lifestyle. There is little or nothing left in his life to repair or resurrect. He is in need of a new lifestyle and renovation of his behavior patterns, which is exactly what a TC has to offer. He may be reaching a state of desperation necessary for him to make the commitment needed to succeed in the TC environment.

These examples illustrate the fact that treatment in a TC is not appropriate for every person with a drug or alcohol problem. The commitment of time, money, and surrender to the program is significant. What makes the dentist in Case 4 a good candidate for a TC is clear from that illustration. His life is in crisis, he is unable to maintain abstinence, his social and interpersonal dysfunction has permeated every aspect of his life, and he has begun to display the antisocial lifestyle typical of end-stage addicts.

If such a patient has the good fortune to cross paths with a physician who is perceptive and knowledgeable enough to refer him to an appropriate addiction TC, he may have a chance to survive. In fact, in some ways, he actually may have a better chance than someone such as the engineer in Case 2.

Many patients seem to do better with a little external motivation. In the case of the dentist, the state diversion program may impose some requirements that will help him to remain focused on his recovery while going through the tough times of personal redevelopment in the TC process.

Requirements imposed through probation or parole orders can be helpful as well. Such requirements may sound harsh but are appropriate when balanced with the fact that the patients have a fatal illness and have failed at every other form of therapy. Admission to a TC may be the only defense between the addict and death in the street.

Outcome Studies

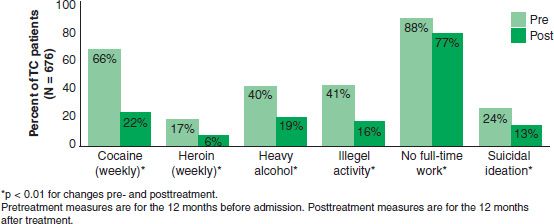

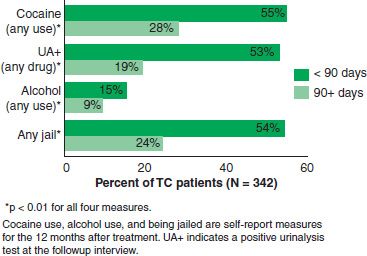

George DeLeon’s (4) pioneering efforts brought credibility and fundability to the TC model (see Appendix). Hubbard et al. (7) (Fig. 61-1) found that even those who did not achieve complete abstinence showed significant improvement in term of frequency of drug use, illegal activity, full-time work, and psychiatric factors. The work of Simpson et al. (8) (Fig. 61-2) showed that longer lengths of stay in residential treatment resulted in dramatically better outcomes over a variety of parameters.

FIGURE 61-1 Pre-and posttreatment self-reported changes among those in long-term residential TCs. (Reprinted from Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, et al. Overview of one-year follow-up outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav 1997;11:261–278, with permission.)

FIGURE 61-2 One-year outcomes for shorter and longer stays in TC treatment. (Reprinted from Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav 1997;11:294–307, with permission.)

Application to Specific Population Groups

Those dealing with specific subpopulations have not overlooked the powerful rate of successful outcome of the therapeutic community. In particular, prison, adolescent, and dually diagnosed persons all have good recovery rates in TC programs. Broader applications are now being evaluated.

CRITICISMS OF THE THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY MODEL

Critics of TCs generally fall into one of two groups: those who believe that TCs cost too much and those who believe that the treatment is too harsh.

Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings are available free of charge to participants. Of course, feeding, housing, and treating residents in a 12- to 18-month residential TC program will cost more than free self-help meetings. That is why this modality is reserved for those who have failed at lesser forms of treatment, usually on more than one occasion. However, TC treatment costs just a fraction of incarceration—usually about one-third the price per resident per year. Even that cost is easily recouped by the lower rates of relapse or recidivism in TC programs. Additional potential savings are found in increased employment, responsibility for self and family, and reduced cost to health care system through avoidance of addiction-related diseases.

The “rough edges” of TC life have been smoothed over the years in response to public opinion and payer oversight. Still, treatment in the modern addiction TC is the most difficult thing most residents will ever do. Generally, TC treatment is reserved for those who have had multiple treatment failures and who are at high risk of dying of the disease. The goal of the modern addiction TC is to rebuild human lives from the ground up. Some struggle and effort are required to achieve that change.

CONCLUSIONS

The modern addiction TC is a powerful therapeutic tool with broad application to changing human behavior. With roots in ancient times, the TC evolved out of AA into a highly structured, often publicly funded, highly successful therapeutic modality. The Daytop model has developed into a traditional TC agency and has been the progenitor of TC programs around the world. Despite its shortcomings, the TC has returned hundreds of thousands of “hopeless” addicts and alcoholics to useful, productive lives (9–40).

|

Overview of Therapeutic Community Outcome Research Stanley Sacks, PhD |

The effectiveness of community-based TCs in achieving positive outcomes for drug use, criminality, and employment has been documented in a number of single-site (1–7) and multi-site studies employing pre- and postde-signs (8–10). Studies of TC programs have also clarified the contribution of retention to the ultimate effectiveness of TC treatment, finding lower rates of drug use and criminal behavior, and higher rates of employment for clients who stayed in programs for longer periods of time (4,11,12).

Three national, multisite, longitudinal evaluations have made particular contributions to an understanding of the effectiveness of community-based TCs, the Drug Abuse Reporting Program (DARP), the Treatment Outcome Prospective Study (TOPS), and the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Two of these, DARP and TOPS, documented large decreases in opiate use and criminal involvement following treatment (10,12–16). Findings from DATOS, the most recent and comprehensive of these evaluations, showed major reductions in all types of drug use for TCs and other residential programs, independent of length of exposure to treatment; specifically, reductions of 66% in cocaine and heroin use, of 50% in weekly or more frequent alcohol or marijuana use, of 60% in predatory illegal behavior, and of 50% in suicidal thoughts and/ or attempts were documented at 1-year posttreatment (9). Even larger reductions were evident for those who stayed in treatment 3 months or longer, and those who successfully completed treatment in a TC had significantly lower levels of cocaine, heroin, and alcohol use; criminal behavior, unemployment; and indicators of depression relative to their functioning prior to entering treatment, improvements that were maintained 5 years later (17–19). A recent National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) publication in the Research Report Series reviewed three decades of research into TC treatment, including baseline data from over 65,000 individuals, and found that participation in a TC was associated with several positive outcomes (20).

Recently, De Leon (21) conducted a comprehensive review of research on TCs in North America. The review included (a) field effectiveness studies that consisted of large-scale multi-modality surveys as well as uncontrolled “case studies”; (b) controlled comparison studies of TCs and TCs modified for special populations (e.g., criminal justice, mentally ill); (c) published statistical meta-analytic studies that involved TCs; (d) evidence from econometric studies; and (e) additional evidence from social- psychological research apart from TCs. De Leon concluded that “the present survey of outcome research from multiple sources categorically answers yes to question posed at the outset. Namely, the TC is an evidence-based treatment approach.

The evidence consistently confirms the hypothesis that the TC is an effective and cost-effective treatment for certain subgroups of substance abusers” (21) (p. 125).

The effectiveness of TCs, especially in obtaining reductions in criminality, provided the empirical basis for extending TC models to correctional settings. Randomized studies have shown that therapeutic community services adapted to correctional settings have achieved significantly greater reductions in recidivism to drugs and to crime (22). The most significant reductions (i.e., of greater magnitude and sustained for longer periods of time) in recidivism have been obtained when institutional care was integrated with aftercare, exemplified by TC work release (23–25) and the postprison TC (26–29). Recent studies have shown that treatment effects producing lower rates of return to custody may persist for up to 5 years (30). A meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of correction-based treatment for drug abuse examined intervention programs reported from 1968 to 1996 and concluded that TC programs are effective in reducing recidivism (31,32).

A recent summary of the literature on substance use treatment in criminal justice reported that positive results were found at multiple time points (12, 24, 36, and 60 months posttreatment), although the treatment and comparison groups normally converge at 36 months, with the exception of those groups that received aftercare (postrelease) treatment. These findings have been interpreted to support the effectiveness of prison treatment for substance use, particularly in combination with continued care in the community postrelease (33).

The demonstrated improvement in psychological well-being during (34–37) and after (38) standard TC treatment provided the rationale for modifying the TC to respond to the concerns of individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders (39). A study of a long-term (1-year) MTC found significantly more positive outcomes for MTC clients on measures of drug use and employment than were obtained for their counterparts receiving the standard care typically provided to homeless clients (40). In a randomized study, conducted in a drug treatment setting, clients showing evidence of co-occurring disorders who received MTC programming achieved more positive mental health outcomes during treatment (significantly greater reductions in symptoms of depression) than those who received standard TC services (41), pointing both to the adaptability of the TC to the needs of particular clients and the importance of making these types of adjustments to programming. An analysis of economic benefits associated with MTC treatment reported $5 of benefit for every dollar spent on MTC treatment (42). Subsequently, the MTC was introduced in prisons to address the complex needs of offenders with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (43), where significant reductions in reincarceration rates (44), and in substance use (45) were observed for those randomly assigned to the MTC compared to those receiving standard mental health treatment services.

Sacks et al. (46) summarized a series of four studies of MTC programs (homeless, prison, outpatient, and HIV/ AIDS aftercare) undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of the approach for clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders compared to alternative treatments. Key features of the MTC were retained in all four studies, but each study tailored its MTC program to suit the needs of the specific population and to fit the requirements of the particular treatment setting. Significantly, better outcomes were observed for the MTC group across four E versus C comparisons on primary outcome measures of substance use, mental health, crime, HIV risk, employment, and housing.

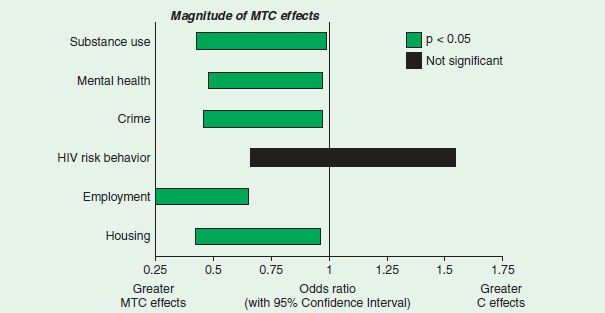

A meta-analysis of studies conducted by a single investigator reported that the MTC produced significantly greater improvements in five domains: substance use (odds ratio = 0.65), mental health (odds ratio = 0.68), crime (odds ratio = 0.66), employment (odds ratio = 0.40), and housing (odds ratio = 0.63)—only HIV-risk behavior failed to show significant treatment effects (i.e., odds ratio = 1.01) (47). The MTC is listed on the National Registry of Effective Programs and Practices (48). A recent review concluded that the “MTC approach has, to date, accumulated sufficient support to encourage policy and program planners to consider its application for persons with co-occurring disorders in a variety of settings” (49) (p. 202).

In summary, a significant body of research, conducted over more than three decades, has demonstrated the effectiveness of community-based TCs and, more recently, of TCs in correctional settings and of MTCs for people with co-occurring disorders. The model is most strongly indicated for very difficult-to-treat individuals who require long-term residential care.

REFERENCES

1.Aron WS, Daily DW. Graduates and splittees from therapeutic community drug treatment programs: a comparison. Int J Addict 1976;11(5):1–18.

2.Barr H, Antes D. Factors related to recovery and relapse in follow-up. Final Report of Project Activities, Grant. No. 1-H81-DA-01864. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1981.

3.Brooke RC, Whitehead IC. Drug free therapeutic community. New York, NY: Human Science Press, 1980.

4.De Leon G. The therapeutic community: Study of effectiveness. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Research Monograph, DHHS Pub. No. ADM 84–1286. Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402, 1984.

5.De Leon G. Alcohol use among drug abusers: treatment outcomes in a therapeutic community. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1987;11(5):430–436.

6.De Leon G. Psychopathology and substance abuse: what we are learning from research in therapeutic communities. J Psychoactive Drugs 1989;21(2):177–187.

7.De Leon G, Rosenthal MS. Treatment in residential communities. In: Karasu TB, ed. Treatment of psychiatric disorders, Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1989:1379–1396.

8.Hubbard RL, Rachal JV, Craddock SG, et al. Treatment outcome prospective study (TOPS): client characteristics and behaviors before, during and after treatment. In Tims FM, Ludford JP, eds. Drug abuse treatment evaluation: strategies, progress and prospects. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Research Monograph 51, DHHS Pub. No. ADM 84–1329. Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402, 1984.

9.Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, et al. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav 1997;11(4): 261–278.

10.Simpson DD, Sells SB. Effectiveness of treatment of drug abuse: an overview of the DARP research program. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse 1982;2(1):7–29.

11.Bale RN, Van Stone WW, Kuldau JM, et al. Therapeutic communities vs methadone maintenance. A prospective controlled study of narcotic addiction treatment: design and one-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37(2):179–193.

12.Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, et al. Drug abuse treatment: a natural study of effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

13.Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Cavanaugh E, et al. Role of drug abuse treatment in limiting the spread of AIDS. Rev Infect Dis 1988;10:377–384.

14.Sells SB, Simpson DD. The case for drug abuse treatment effectiveness, based on the DARP research program. Br J Addict 1980;75:117–131.

15.Simpson DD. Treatment for drug abuse: follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38: 875–880.

16.Simpson DD, Sells SB, eds. Opioid addiction and treatment: a 12-year follow-up. Malabar, FL: Krieger, 1990.

17.Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Follow-up of cocaine-dependent men and women with antisocial personality disorder in DATOS. J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;25(3):155–164.

18.Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Anderson J. Overview of 5-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Studies (DATOS). J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;25(3):125–134.

19.Simpson DD. Introduction to 5-year follow-up treatment outcome studies [Editorial]. J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;25(3):123–124.

20.National Institute on Drug Abuse (2002). Therapeutic Community. NIDA Research Report Series, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved online July 18, 2008 from http://www.nida.nih.gov/PDF/RRTherapeutic.pdf

21.De Leon G. Is the therapeutic community an evidence-based treatment? What the evidence says. Ther Commun 2010;31(2):104–128. Retrieved May 5, 2012 from http://www.drugslibrary.stir.ac.uk/documents/31(2).pdf#page=14

22.Wexler HK, Falkin GP, Lipton DS. Outcome evaluation of a prison therapeutic community for substance abuse treatment. Crim Justice Behav 1990;17(1):71–92.

23.Butzin CA, Martin SS, Inciardi JA. Evaluating components effects of a prison-based treatment continuum. J Subst Abuse Treat 2002;22(2):63–69.

24.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Martin SS, et al. The importance of aftercare in a corrections-based treatment continuum. In: Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, Farabee D, eds. Treatment of drug offenders: policies and issue. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, 2002:204–216.

25.Martin SS, Butzin CA, Saum CA, et al. Three-year outcomes of TC treatment for drug-involved offenders in Delaware: from prison to work release to aftercare. Prison J 1999;79(3):294–320.

26.Griffith JD, Hiller ML, Knight K, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of in-prison TC treatment and risk classification. Prison J 1999;79(3):352–368.

27.Hiller ML, Knight K, Simpson DD. Prison-based substance abuse treatment, residential aftercare and recidivism. Addiction 1999;94(6):833–842.

28.Knight K, Simpson DD, Chatham LR, et al. An assessment of prison-based drug treatment: Texas’ in-prison TC program. J Offender Rehabil 1997;24(3/4):75–100.

29.Wexler HK, Lowe L, Melnick G, et al. Three-year reincarceration outcomes for Amity in-prison and aftercare therapeutic community and aftercare in California. Prison J 1999;79(3):321–336.

30.Prendergast ML, Hall EA, Wexler HK, et al. Amity prison-based therapeutic community: five-year outcomes. Prison J 2004;84(1):36–60.

31.Lipton DS, Pearson FS, Cleland CM, et al. The effects of therapeutic communities and milieu therapy on recidivism. In: McGuire J, ed. Offender rehabilitation and treatment. Chichester, UK: Wiley, 2002.

32.Pearson FS, Lipton DS. A meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of corrections-based treatments for drug abuse. Prison J 1999;79(4):384–410.

33.Wexler HK, Prendergast ML. Therapeutic communities in United States’ prisons: effectiveness and challenges. Ther Commun 2010;31(2):157–175.

34.De Leon G, Jainchill N. Male and female drug abusers: social and psychological status 2 years after treatment in a therapeutic community. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1981;8(4):465–496.

35.De Leon G, Wexler H, Jainchill N. The therapeutic community: success and improvement rates five years after treatment. Int J Addict 1982;17(4):703–747.

36.Jainchill N, De Leon G. Therapeutic community research: recent studies of psychopathology and retention. In: Buhringer G, Platt JJ, eds. Drug addiction treatment research: German and American perspectives, Melbourne, FL: Krieger Publications, 1992:367–388.

37.Sacks S, De Leon G. Modified therapeutic communities for dual disorders: evaluation overview. Proceedings of Therapeutic Communities of America 1992 Planning Conference, Paradigms: Past, Present and Future, December 6–9, 1992, Chantilly, VA.

38.Biase DV, Sullivan AP, Wheeler B. Daytopminiversity— phase 2—college training in a therapeutic community: development of self-concept among drug free addict/ abusers. In: De Leon G, Ziegenfuss JT, eds. Therapeutic community for addictions: readings in theory, research, and practice, Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1986: 121–130.

39.Sacks S, Sacks JY, De Leon G. Treatment for MICAs: Design and implementation of the modified TC. J Psychoactive Drugs (special edition) 1999;31(1):19–30.

40.De Leon G, Sacks S, Staines GL, et al. Modified therapeutic community for homeless MICAs: treatment outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2000;26(3):461–480.

41.Rahav M, Rivera JJ, Nuttbrock L, et al. Characteristics and treatment of homeless, mentally ill chemical-abusing men. J Psychoactive Drugs 1995;21(1):93–103.

42.French MT, McCollister KE, Sacks S, et al. Benefit-cost analysis of a modified TC for mentally ill chemical abusers. Eval Program Plann 2002;25(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/ S0149-7189(02)00006-X

43.Sacks S, Sacks JY, Stommel J. Modified TC for MICA inmates in correctional settings: a program description. Corrections Today 2003:90–99.

44.Sacks S, Sacks J, McKendrick K, et al. Modified TC for MICA offenders: crime outcomes. Behav Sci Law 2004;22: 477–501.

45.Sullivan CJ, McKendrick K, Sacks S, et al. Modified therapeutic community treatment for offenders with MICA disorders: substance use outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2007;33(6):823–832. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653800.

46.Sacks S, Banks S, McKendrick K, et al. Modified therapeutic community for co-occurring disorders: a summary of four studies. In: Sacks S, Chandler R, Gonzales J, eds. J Subst Abuse Treat, Special Issue: Recent advances in research on the treatment of co-occurring disorders. 2008;34(1):112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.008.

47.Sacks S, McKendrick K, Sacks JY, et al. Modified therapeutic community for co-occurring disorders: single investigator meta-analysis. Subst Abuse 2010;31(3):146–161. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.495662.

48.National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP). (2009; updated 2010). Intervention summary: modified therapeutic community for persons with co-occurring disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Rockville, MD. Retrieved April 24, 2012, from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=144

49.Sacks S, Sacks JY. Research on the effectiveness of the modified therapeutic community for persons with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders. Ther Commun 2010;31(2):176–212 (Summer 2010). Modified Therapeutic Community for Persons with Co-Occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders

|

Modified Therapeutic Community for Persons with Co- Occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders Stanley Sacks, PhD |

BACKGROUND

Jones (1) and others in the United Kingdom pioneered TCs in psychiatric hospitals a decade before drug-free residential programs for substance abuse appeared. Although these two models arose independently, both adopted the therapeutic community name to describe the program. In the treatment of psychiatric patients, Jones postulated the importance of open communication, democratic decision making, a flattened staff hierarchy, therapeutic input from both staff and clients, and large group meetings held daily to address the issues of the moment. To examine life in a TC, an American social anthropologist, Robert Rappaport, adopted the role of participant–observer and entered the Belmont TC. He extracted four themes: permissiveness, communalism, democracy, and reality confrontation that became the main principles of this model. This form of TC continued to develop in England and other parts of Europe, becoming known as the “Democratic TC,” (1) while TCs for substance abusers were called “Concept TCs.” A special issue of the Psychiatric Quarterly (2) reviewed the history, functioning, adaptations, and research associated with the Democratic TC (3–6).

Recovering alcoholics and drug addicts were the developers and first participants of the TC for substance abuse as it emerged as a self-help alternative to conventional treatments in the United States during the 1960s. Although the modern antecedents of the TC can be traced to Alcoholics Anonymous, Synanon, and Daytop Village, the TC prototype is ancient, manifest in all forms of communal healing and support. In a review of the literature, Lees et al. (4) attributed the evaluation research of De Leon (examples of which are cited below) with being central to this TC movement: “The positive results demonstrated through these evaluation studies have played a large part in developing the therapeutic community into a major global player in the drug treatment field” (4) (p. 280).

The demonstrated improvement in psychological well-being (7–10) and self-concept (11) following traditional TC treatment provided the rationale for modifying the TC to respond to the multiple needs of individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders. As TCs began adapting to clients with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders (then known as “dual disorders,” among other terms; today, commonly called “co-occurring disorders”), three models emerged: an “inclusive” model, in which community-based TCs admitted a small number of clients with co-occurring disorders, often developing a specialized track within the program for such clients; an “ancillary service” model, in which clients with co-occurring disorders functioned within the traditional TC and received enriched mental health services concomitant to their TC programming; and an “exclusive” or “stand-alone” model designed specifically for co-occurring disorders. This latter model, wherein the treatment environment and most of its accompanying interventions are modified to incorporate features that address both substance abuse and psychiatric symptoms, treats both disorders as equally important (12).

Over time, TCs adapted to changing needs and populations, to different settings, and to advances in research and practice. In the early and mid-1990s, the modified TC (typically abbreviated as “MTC”), described here, was developed from the theoretical framework of the traditional TC model, as detailed in the definitive text, The Therapeutic Community: Theory, Model and Method (13), adapted to treat individuals with co-occurring disorders (12,14–17). The use of “modified TC” or “MTC,” in this report is intended to capture those adaptations of the TC model designed to serve substance-abusing individuals with co-occurring mental disorders, most of which were serious (i.e., schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, and major depression) mental disorders (16).

DESCRIPTION OF THE MODIFIED TC PROGRAM

TC Principles and Methods

The TC principles and methods of particular relevance to co-occurring disorders include the following:

• A highly structured daily regimen

• Coping with life’s challenges with personal responsibility and self-help; using the peer community as the healing agent within a strategy of “community-as-method” (the community provides both the context for and mechanism of change)

• Assigning role models and guides from within the peer group

• Viewing change as a gradual, developmental process, wherein clients advance through stages of treatment; emphasizing work and self-reliance through the development of vocational and independent living skills

• Adopting prosocial values within healthy social networks to sustain recovery

Modifications

The MTC model* retains, but reshapes, most of the central elements, structure, and processes of the traditional TC, so as to accommodate the many needs that accompany co-occurring disorders, particularly, psychiatric symptoms, cognitive deficits, and reduced level of functioning. A key alteration is the change from the encounter group to the conflict resolution group. As compared to a standard encounter group, the conflict resolution group has shorter duration, reduced intensity of interaction, more emphasis on instruction, and increased modeling by staff and more experienced clients. The conflict resolution group focuses on personal conflicts, conflicts between people, and conflicts in relation to an individual’s performance of program tasks and activities. The goals of this group are the same as those of a standard encounter group; specifically, to identify and modify self-defeating patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving and to facilitate self-discovery through personal disclosure and direct interpersonal interaction.

Other alterations in the MTC for co-occurring disorders include

• More flexibility in program activities

• Shorter duration of various activities

• Less confrontation and intensity of interpersonal interaction

• Greater emphasis on orientation and instruction in programming and planning

• Fewer sanctions and greater opportunity for corrective learning experiences

• More explicit affirmation for achievements

• Greater sensitivity to individual differences

• Greater responsiveness to the special developmental needs of the clients

To summarize, three key alterations were made in designing the MTC program for co-occurring disorders: increased flexibility, decreased intensity, and greater individualization. Still, the MTC, like all TC programs, promotes a culture wherein self-help advances learning and promotes change, both in themselves and in others. In other words, the community becomes the agent of healing. Thus, this variant of the TC also shares certain features with the psychiatric (Democratic) TC that emerged in England and elsewhere in Europe.

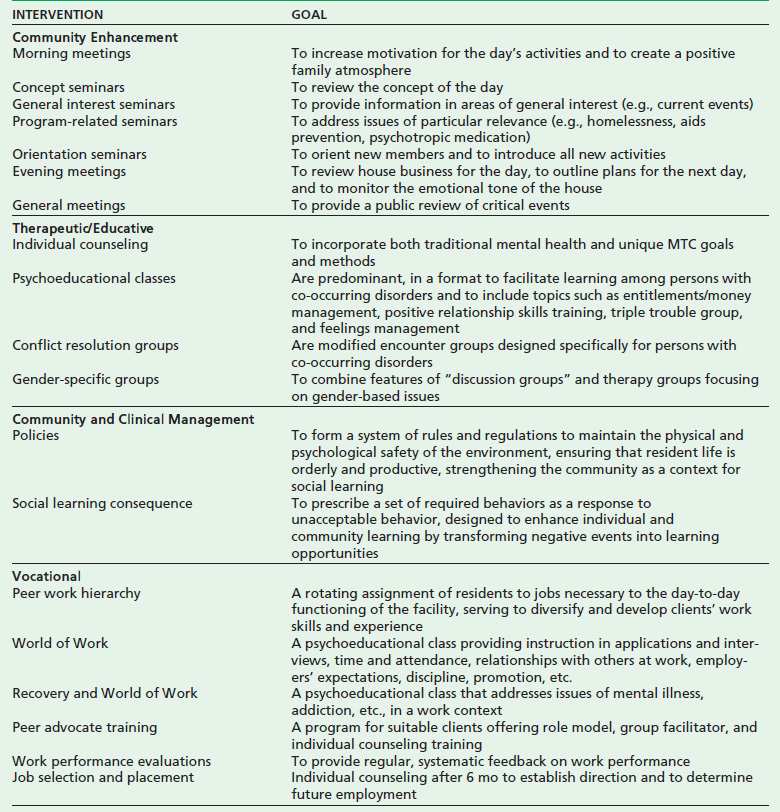

Interventions

The basic MTC program, delivered over a planned stay of 12 months, is a highly structured, comprehensive residential program that consisted of multiple interventions organized in four areas:

• Community Enhancement—to facilitate the individual’s assimilation into the community and reaffirm the individual’s commitment to recovery (e.g., Morning meeting, Orientation Seminars, General Meetings)

• Therapeutic/Educative—to promote self-expression, divert acting-out behavior, and resolve personal and social issues (e.g., Individual Counseling, Dual Recovery Classes, Conflict Resolution Groups)

• Community and Clinical Management—to maintain the physical and psychological safety of the environment and ensure that residential life is orderly and productive (e.g., Program Policies, Social Learning Consequences)

• Work/Vocational—to promote positive work attitudes and develop work skills (e.g., Peer Work Hierarchy, Vocational Counseling)

All program activities and interactions, singly and in combination, are designed to produce change. Implementation of the groups and activities listed in Table 61-6 are necessary to establish the TC community. Although each intervention has specific individual functions, all share community, therapeutic, and educational purposes.

TABLE 61-6 RESIDENTIAL INTERVENTIONS

Adapted from Sacks S, Sacks JY, De Leon G. Treatment for MICAs: design and implementation of the modified TC. J Psychoact Drugs (special edition) 1999;31(1):19–30.

Outcomes

Research has established a considerable evidence base for the MTC model. A study of a long-term (1-year) MTC found significantly more positive outcomes for MTC clients on measures of drug use and employment than were obtained for their counterparts receiving the standard care typically provided to homeless drug-abusing clients (13). Another study of a long-term (1-year) MTC found significantly more positive outcomes for MTC clients on measures of drug use and employment than were obtained for their counterparts receiving the standard care typically provided to homeless clients (18). Economic analysis of MTC treatment reported $5 of benefit for every dollar spent on MTC treatment (19).

Subsequently, the MTC has been introduced in prisons to address the complex needs of offenders with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (20), and has shown significant reductions in reincarceration rates (21), and substance use (22) for clients randomly assigned to the MTC compared to those receiving standard mental health treatment services.

In a single-investigator meta-analysis of these and two other studies (23,24) (Fig. 61-3), the MTC produced significantly greater improvements in five domains; substance use (odds ratio = 0.65), mental health (odds ratio = 0.68), crime (odds ratio = 0.66), employment (odds ratio = 0.40), and housing (odds ratio = 0.63)—only HIV-risk behavior failed to show significant treatment effects (i.e., odds ratio = 1.01) (25). Thus, there is a substantial research base for the MTC model.

FIGURE 61-3 MTC meta-analysis of four comparisons from three studies.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Continuity of Care

Rationale

The evidence available suggests that co-occurring substance use and mental disorders, especially serious mental disorders, have chronic features that require extended residential treatment followed by period of community-based support (i.e., continuing care) to solidify the successes achieved with MTC. Continuity of care implies coordination of care as clients move across different service systems and is characterized by three features: consistency among primary treatment activities and ancillary services; seamless transitions across levels of care (e.g., from residential to outpatient treatment); and coordination of present with past treatment episodes. Because both substance use and mental disorders are typically long term, continuity of care is critical; the challenge in any system of care is to institute mechanisms to ensure that all individuals with co-occurring disorders experience the benefits of continuity of care.

MTC Residential Aftercare Models

In examining continuity of care, Sacks et al. conducted a series of studies among special populations of persons with co-occurring disorders (summarized in (26)); the co-occurring population in one of these studies was homeless persons (27), and in another was offenders (21). The MTC aftercare programs in these two studies retained the core features of the MTC but added elements specific to the co-occurring disorder population being treated and that were necessary for reintegration with mainstream living.

The aftercare program in the study of homeless persons with co-occurring disorders was conducted in a supported housing facility and consisted of community meetings (held in the supported housing facility), with continued treatment and support groups held in an associated day treatment program (located outside the supported housing facility). In addition to co-occurring disorder treatment and support, this aftercare program emphasized housing and employment (27).

In a study of offenders with co-occurring disorders (20,21), the aftercare program that was housed in a Community Corrections apartment-like facility consisted of community and peer support meetings with certain treatment services provided at local community treatment facilities. Along with co-occurring disorders treatment and support, this aftercare program incorporated elements related to criminal thinking and behavior, as well as employment (20). In general, quasi-experimental studies suggest that aftercare programs sustained the gains of the more intensive residential MTC facilities (27,21,24,25).

Modified TC Outpatient Models

Despite the fact that outpatient substance abuse programs are not typically equipped to provide services for mental conditions, let alone the accompanying health and social problems, many of the clients who enter these programs, have a co-occurring mental condition. Sacks and colleagues developed an outpatient MTC model, the Dual Assessment and Recovery Track (DART), for persons with co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders. A study of the model’s effectiveness demonstrated that, compared to the control condition, the DART group had significantly better outcomes on measures of psychological symptoms as well as on a key measure of housing stability (i.e., “lived where paid rent”), which indicated that the DART group had acquired more stable housing (24). The MTC features of this program were designed to strengthen identification with the community (i.e., community meetings); to teach clients about mental illness in a Psycho-Educational Seminar (28–30); to assist clients to cope with trauma within the context of addictions and recovery using the Trauma-Informed Addictions Treatment approach (31–33); and to expand clients’ ability to negotiate health and social service agencies using case management skills, imparted through a Case Management component (34–36).

The Medically Integrated Therapeutic Community

The Affordable Care Act affords an opportunity for the continued adaptation and growth of the MTC model, which is ideally suited for alterations to support integration with primary care services. The rational for such an approach is based on the fact that the conceptual framework of the MTC (and the TC) endorses a view of “whole person” treatment that is compatible with holistic medicine, and the model has been modified in the past to suit special populations, retaining core TC principles while adding interventions to accommodate particular services. Further, the central feature of TC methods (i.e., “Community-as-Method,” wherein the community of patients becomes the healing agent) can be naturally extended to include substance abuse, mental health, and primary care services. In fact, the residential MTC model already encompasses much of this integration in its existing provision of services. In requiring an onsite psychiatrist to prescribe and monitor psychotropic medication, the MTC for co-occurring disorders sets the stage for additional integration. Furthermore, the MTC requires integrated team planning and coordination of both residential and aftercare services.

In developing the Medically Integrated Therapeutic Community (MITC), the following service components are recommended for inclusion: integrated primary and behavioral care becomes the agency’s primary focus and is so stated in the mission statement; a welcoming social and interpersonal environment for patients with medical problems is evident; routine screening and assessment for medical problems is established; teams develop Integrated treatment plans; medical conditions are considered in the process of planning for discharge or during a postacute stabilization phase; onsite staff have medical expertise and prescribing authority; and all program staff members have basic training in life support, infectious diseases and infection on control, and patient privacy/confidentiality, according to a formal agency plan. Finally, in the articulation of its services, each program will need to determine the extent of medical services to be provided, the use of referral resources and their broader relationship with the medical community.

SUMMARY

During the past 20 years, an MTC model has been articulated for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, and a series of studies has established a research base for the model. The National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices recognizes and lists the MTC model (37). The proposed development of the Medically Integrated Therapeutic Community represents a natural evolution for the MTC model, one that promises to improve health care through the integration of mental health, substance abuse, and primary care services.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work reported in this manuscript was supported by grant 1 UD3 SMTI51558, Modified therapeutic community for homeless MICAs: Phase II Evaluation—TC-Oriented Supported Housing for Homeless MICAs, from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS)/Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), Cooperative Demonstration Program for Homeless Individuals; grant 2 P50 DA07700.0003, Modified TC for MICA Inmates in Correctional Settings, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); grant 5 KD1 TI12553, Dual Assessment and Recovery Track for Co-Occurring Disorders, from SAMSHA, CSAT, GFA TI 00–002 Grants for Evaluation of Outpatient Treatment Models for Persons with Co-Occurring Substance Abuse and Mental Health Disorders (short title Co-Occurring Disorders Study); and grant 1 UD1-SM52403, Integrated Residential/Aftercare TC for HIV/AIDS and Comorbid Disorders, CMHS with Health Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health, NIDA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, GFA No. SM 98.007, FCFDA No. 93.230, Cooperative Agreements for an HIV/AIDS Treatment Adherence, Health Outcomes, and Cost Study.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA, CSAT, or the NIH, NIDA.

REFERENCES

1.Jones M. The concept of a therapeutic community. Am J Psychiatry 1956;112:647–650.

2.Special Section: The therapeutic community in the 21st century. Psychiatr Quart. Norton K, Bloom SL. eds. 2004;75(3):229–307.

3.Haigh R, Tucker S. Democratic development of standards: the community of communities—a quality network of therapeutic communities. Psychiatr Q 2004;75(3):263–277. doi: 10.1023/B: PSAQ.0000031796.66260.b7.

4.Lees J, Manning N, Rawlings B. A culture of enquiry: Research evidence and the therapeutic community. Psychiatr Q 2004; 75(3):279–294. doi: 10.1023/B:PSAQ.0000031797.74295.f8.

5.Norton K, Bloom SL. The art and challenges of long-term and short-term democratic therapeutic communities. Psychiatr Q 2004;75(3):249–261. doi: 10.1023/B:P SAQ.0000031795.54790.26.

6.Whiteley S. The evolution of the therapeutic community. Psychiatr Q 2004;75(3):233–248. doi: 10.1023/B: PSAQ.0000031794.82674.e8.

7.De Leon G, Jainchill N. Male and female drug abusers: social and psychological status 2 years after treatment in a therapeutic community. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1981;8(4): 465–497. doi: 10.3109/00952998109016931.

8.De Leon G, Wexler H, Jainchill N. The therapeutic community: success and improvement rates five years after treatment. Int J Addict 1982;17(4):703–747.

9.Jainchill N, De Leon G. Therapeutic community research: recent studies of psychopathology and retention. In: Buhringer G, Platt JJ, eds. Drug addiction treatment research: German and American perspectives, Melbourne, FL: Krieger, 1992:367–388.

10.Sacks S, De Leon G. Modified therapeutic communities for dual disorders: evaluation overview. Proceedings of Therapeutic Communities of America 1992 Planning Conference, Paradigms: Past, Present and Future, December 6–9, 1992, Chantilly, VA.

11.Biase DV, Sullivan AP, Wheeler B. Daytopminiversity—phase 2—college training in a therapeutic community: development of self-concept among drug free addict/abusers. In: De Leon G, Ziegenfuss JT, eds. Therapeutic community for addictions: readings in theory, research, and practice. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1986:121–130.

12.Sacks S, Sacks JY, De Leon G. Treatment for MICAs: design and implementation of the modified TC. J Psychoactive Drugs (special edition) 1999;31(1):19–30.

13.De Leon G. The therapeutic community: theory, model and method. New York, NY: Springer Publishers, 2000:472.

14.De Leon G. Modified therapeutic communities for co-occurring substance abuse and psychiatric disorders. In: Solomon J, Zimberg S, Shollar E, eds. Dual diagnosis: evaluation, treatment, and training and program development. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation, 1993:137–156.

15.Sacks S, De Leon G, Bernhardt AI, et al. A modified therapeutic community for homeless MICA clients. In: De Leon G, ed. Community-as-method: therapeutic communities for special populations and special settings. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997.

16.Sacks S, Sacks JY, De Leon G, et al. Modified therapeutic community for mentally ill chemical “abusers”: background; influences; program description; preliminary findings. Subst Use Misuse 1997;32(9):1217–1259.