24

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Drug addiction is a complex illness. Compulsive (at times uncontrollable) drug seeking and use, which persist even in the face of extremely negative consequences, characterize the disorder. For many patients, drug addiction is a chronic disease, with relapses possible even after long periods of abstinence. Patients with substance use disorders are heterogeneous in a number of clinically important features and domains. Because addiction has so many dimensions and disrupts so many aspects of an individual’s life, treatment for this illness never is simple; generally, a multimodal approach to treatment is required. Drug treatment must help the individual stop using drugs and maintain a drug-free lifestyle while achieving productive functioning in the family, at work, and in society. After repeated failures of appropriately matched treatment, some individuals are deemed unable to stop using drugs. In this instance, it is appropriate to work to achieve intermediate outcomes that include a reduction in the use and effects of substances, reduction in frequency and severity of relapse to substance use, and improvement in psychological and social functioning. Physicians are cautioned that the latter is hard to achieve with continued drug use.

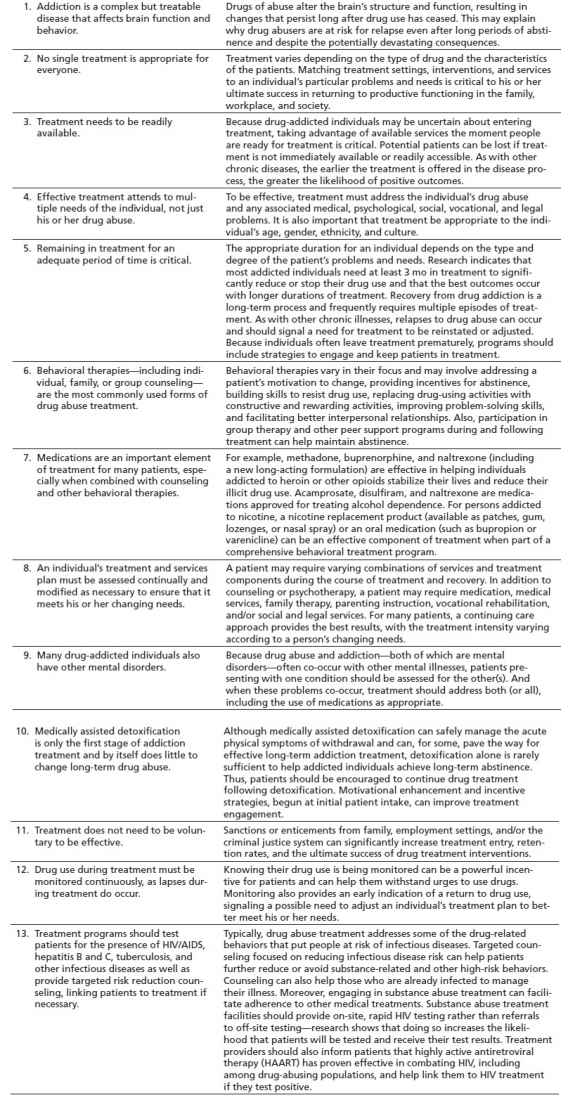

Effective treatment programs typically incorporate many components, each directed to a particular aspect of the illness and its consequences. In practice, specific pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments are often combined because combined treatments lead to better treatment retention and outcomes (1). Three decades of scientific research and clinical practice have yielded a variety of approaches to addiction treatment; the most effective match the patient’s assessed needs to services that, research suggests, might have the most impact. Evidence suggests that substance-dependent individuals who achieve sustained abstinence from the abused substance have the best long-term outcomes (2,3). Extensive data show that such treatment is as effective as treatment for most other chronic medical conditions (4). Of course, not all drug treatment is equally effective or applied in a standardized way. To overcome inconsistency and to improve fidelity to conceptualized models, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has manualized therapies. Research also has revealed a set of overarching principles that characterize the most effective drug addiction treatments and their implementation (Table 24-1).

TABLE 24-1 PRINCIPLES OF EFFECTIVE TREATMENT

From National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: a research-based guide, 3rd ed. Rockville, MD: NIDA (NIH Publication No. 12–4180), 1999:2–5.

GOALS OF DRUG ADDICTION TREATMENT

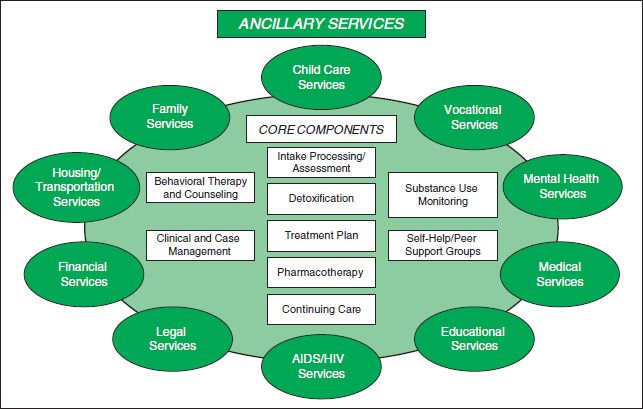

Drug addiction is a complex disorder that can involve virtually every aspect of an individual’s functioning—in the family, at work, and in the community. Because of addiction’s complexity and pervasive consequences, addiction treatment typically must involve many components. Some of those components focus directly on the individual’s drug use, whereas others, such as employment training, focus on restoring the addicted individual to productive membership in the family and society (Fig. 24-1). Treatment of drug abuse and addiction is delivered in many different settings, using a variety of behavioral and pharmacologic approaches. In the United States, more than 11,000 specialized drug treatment facilities provide rehabilitation, counseling, behavioral therapy, medication, case management, and other types of services to persons with drug use disorders.

FIGURE 24-1 Components of addiction treatment. (From National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment—a research-based guide, 3rd ed. NIH Publication No. 12–4180, 2012.)

Care of individuals with substance use disorders includes assessing needs, providing treatment for intoxication and withdrawal, and developing, with appropriate support, the treatment plan that may consist of referrals to psychosocial care. The treatment plan should address how the patient will achieve abstinence without medical compromise, achieve and maintain abstinence after withdrawal, and gain improvement in functioning in the medical, social, and psychological domains.

TREATMENT SETTINGS

The addiction treatment delivery system is primarily a specialty care delivery system, often separate from the medical–surgical delivery system. Funding for care in the system is usually separate, and the professionals in the system are different. Treatment settings vary widely with regard to services and medical support available and the milieu or philosophy. For physicians, assessment for treatment matching and knowledge of referral and funding options in the community are important, as every community is different. Hospital social work departments generally know the local resources, and health maintenance organization case managers can assist with locating specialty providers of addiction medicine. Mental health carve-outs make accessing care complicated for the patient, and physicians may not be allowed to refer to preferred providers who are out of the network of care. Underinsurance for addiction care is common, and benefit limits (any coverage) or lifetime caps (remaining coverage) may preclude care for patients relapsing following prior treatment.

Decisions regarding the site of care should be based on the patient’s ability to cooperate with and benefit from the treatment offered, to refrain from illicit use of substances, and to avoid high-risk behaviors, as well as the patient’s need for structure and support or particular treatments that may be available only in certain settings. Patients move from one level of care to another based on these factors and an assessment of their ability to benefit from a different level of care. Delivery system discontinuities occur when coverage is available for a limited number of levels of care, but not the one indicated based on the assessment carried out using a standardized system such as the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Patient Placement Criteria (PPC). ASAM PPC describes four levels of care: (a) general outpatient, (b) intensive outpatient or day hospital, (c) medically monitored inpatient residential care, and (d) medically managed inpatient care. An in-hospital consultant or a member of the medical staff who is knowledgeable and interested in patients with addictive disorders can make criterion-based placement. Sometimes, the payer will insist that external case managers employed by the payer make criterion-based decisions. In some instances, placement decisions are not criteria based.

Hospital-based physicians may find their management of addiction limited to detoxification and referral. It is uncommon to refer outside of the hospital, because either the payer requires referral to a contracted provider or the patient lacks coverage and needs referral to the public system of care. Hospital-based physicians can create an inpatient Addiction Medicine Consultation Service with specialty-trained clinicians and nonphysician clinicians who assess addiction severity and withdrawal potential, manage withdrawal, and refer to posthospital addiction care when the patient no longer requires care in the hospital setting.

Detoxification

According to ASAM PPC-2R, detoxification refers not only to the attenuation of the physiologic and psychological features of withdrawal syndromes but also to the process of interrupting the momentum of compulsive use in persons diagnosed with substance dependence (5). This phase of treatment frequently requires a great intensity of treatment to establish treatment engagement and patient role induction. It can be delivered in ambulatory settings with and without extended on-site monitoring. In residential or inpatient settings, it is delivered under clinically managed, medically monitored, or medically managed conditions. There is increasing intensity of services and involvement of nursing and medical personnel across the latter continuum. A full description of services available in each setting can be found elsewhere in this text.

Hospital Settings

Hospitalization is appropriate for patients whose assessed need cannot be treated safely in an outpatient or emergency department setting because of (a) acute intoxication, (b) severe or medically complicated withdrawal potential, (c) co-occurring medical or psychiatric conditions that complicate detoxification or impair treatment engagement and response, (d) failure of engagement in treatment at a lower level of care, (e) life- or limb-threatening medical conditions that would require hospitalization, (f) psychiatric disorders that make the patient an imminent threat to self or others, and (h) failure to respond to care at any level such that the patient endangers others or poses a self-threat. Aside from detoxification and management of overdose or intoxication, most patients are receiving services incident to a medical–surgical need to manage a biomedical condition or complication or a psychiatric need to manage an emotional or behavioral condition in a primary psychiatric setting. The physician must evaluate the timing and intensity of addiction medicine services in the context of other concerns.

Partial Hospital Programs and Intensive Outpatient

Partial hospitalization is considered for patients who require intensive care but have a reasonable chance of making progress on treatment goals in the intertreatment interval, including maintenance of abstinence. It is often provided to individuals whose treatment is hospital or residential initiated and who still require frequent and concentrated contact with treatment professionals to monitor their behavior and manage their risk of relapse. These patients often have a history of relapse after completion of treatment or are returning to a high-risk environment and have a need to develop support for their recovery-focused efforts beyond the treatment system. Lack of motivation to continue to build on the gains made in the treatment, allowing the treatment effect to erode, is often cause to continue the patient in this highly intensive and structured setting. Intensive outpatient programs have been proven to be effective when working with special subgroups of patients, such as those who are economically disadvantaged, psychiatrically compromised, and pregnant or who have been coerced into treatment by the criminal justice system or outside parties (6). The difference between partial hospital programs and intensive outpatient is seen in intensity, number of hours per day, setting of the program, and structure of the program. Patients who are not successful in intensive outpatient may have clinical contact increased by transfer to partial hospital programs.

Outpatient Programs

This treatment varies in the types and intensity of services offered, ranging from specialty programs to individual physician offices and primary care settings. It costs less than residential or inpatient treatment and often is more suitable for individuals whose ASAM PPC shows insight into his or her disease, a high degree of predicted compliance, low symptomatology, high resource availability and use, and a supportive structure in his or her home environment. Low-intensity programs may offer little more than drug education and admonition; however, as in the other treatment settings, a comprehensive approach is optimal, using— where indicated—a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic interventions along with behavioral monitoring. High rates of attrition can be problematic, particularly in the early phase. Because outcomes are highly correlated with time in treatment, retention should be one focus of treatment, along with self-efficacy regarding adherence to the abstinence plan. Self-help participation is useful (7).

Other outpatient models, such as intensive day treatment, can be comparable to residential programs (see below “Residential Programs, Including Therapeutic Community”) in services and effectiveness, depending on the individual patient’s characteristics and needs. In many outpatient programs, as in much of treatment in general, group counseling is emphasized. Some outpatient programs are designed to treat patients who have medical or mental health problems in addition to their drug disorder (8).

Most alcohol abuse and dependence are treated outside of the hospital after medical complications associated with detoxification are addressed (9,10). Similarly, cocaine abuse and dependence (11), nicotine dependence (12), and marijuana abuse and dependence are treated on an outpatient basis as long as the focus on reduced substance use can be maintained and there are no other reasons for hospitalization (13,14).

RESIDENTIAL PROGRAMS, INCLUDING THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

Residential programs provide care 24 hours a day, generally in nonhospital settings. Residential care is generally provided to patients who do not meet the clinical criteria for hospitalization but whose lives are transformed by and focused on substance use. These individuals are unlikely to maintain abstinence in the absence of continued application of a variety of therapeutic techniques in a highly structured and supportive environment. Short-term programs provide intensive but relatively brief residential treatment based on a modified 12-step approach and may or may not include elements of therapeutic communities (TCs) (see the following paragraph). The duration of residential treatment should be determined by the clinical response to therapy and the length of time necessary for the patient to meet specific criteria predictive of success in a lower level of care according to ASAM PPC. In general, longer programs provide better outcomes (15). These programs originally were designed to treat alcohol problems, but during the cocaine epidemic of the mid-1980s, many began to treat illicit drug abuse and addiction. The original residential treatment model consisted of a 3- to 6-week hospital-based inpatient treatment phase, followed by extended outpatient therapy and participation in a self-help group such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Reduced health care coverage for addiction treatment has resulted in a diminished number of these programs, and the average length of stay under managed care review is much shorter than in early programs.

One residential treatment model is the TC, but residential treatment programs also employ other models, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy. TCs are residential programs with planned lengths of stay from 6 to 12 months. TCs focus on the “resocialization” of the individual and use the program’s entire “community”—including other residents, staff, and the social context—as active components of treatment. Addiction is viewed in the context of an individual’s social and psychological deficits, so treatment focuses on developing personal accountability and responsibility and socially productive lives. Treatment is highly structured and can at times be confrontational, with activities designed to help residents examine damaging beliefs, self-concepts, and patterns of behavior and to adopt new, more harmonious and constructive ways to interact with others. Many TCs are quite comprehensive and include employment training and other support services on-site or through formal linkage agreements. Compared with patients in other forms of drug treatment, the typical TC resident has more chronicity and criminal involvement. Research shows that TCs can be modified to treat individuals with special needs, including adolescents, women (16,17), those with severe mental disorders (18), and individuals in the criminal justice system. Recently, with pressure from reimbursement sources, the elements of TCs have been incorporated into shorter-term residential programs and institutional criminal justice settings.

Heroin addiction has been effectively treated in the TC; however, return to use rates after TC treatment is higher than 80% in most long-term follow-up studies, indicating a need for selectivity in application of this modality over medication-assisted clinical settings (19). Data regarding the effectiveness of traditional long-term TC are limited by the low completion rates of 15% to 25%, with most attrition occurring during the first 3 months (20). Retention lengths predict outcomes on abstinence with abstinence success rates of 90% for graduates of 2-year programs and 25% for dropouts of the same programs completing less than 1 year (21). Retention rates differ with program sites (22).

Community Residential Rehabilitation

Community residential rehabilitation facilities include “halfway houses” or “sober living facilities,” with the former providing more structure and supervision. Individuals referred to these settings are generally deemed to be at risk for relapse without such support. Often, this setting is offered to the individual whose environmental risk is great or those needing a number of services after primary treatment to address deficits in vocation, employment, and social supports. These services have been shown to significantly improve substance use outcomes for both sexes, but are variable in their impact on young people (23–25).

Case Management

Case management is a collaborative process that assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors, and evaluates the options and services to meet an individual’s health needs (26). It uses communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes.

Case management, although difficult to assess for effectiveness in a rigorous fashion, has been shown to be an effective adjunctive treatment for patients with alcohol use disorders, patients with substance use disorders co-occurring with psychiatric disorders (26), and adolescents (27). Case management is provided to individuals whose social situation and complex needs would impair their ability to adhere to a prescribed treatment plan and follow-up care. Basic needs are often met as part of the service array, which includes as psychoeducation and assistance in comprehension of the extent and nature of the disease for which treatment is provided and advocated (28,29).

Aftercare Programs

Aftercare generally follows an episode of care and is focused on maintenance of gains made in treatment over a prescribed period with less frequent contact than the primary episode of care (e.g., once-weekly monitoring and group therapy after a 6-week intensive outpatient program in which the patient is seen nightly for 3 hours). The patient’s affiliation with a 12-step program is encouraged, and the transition to self-efficacy is monitored.

Treatment in the Physician’s Office, Including Screening and Brief Interventions

The addiction treatment enterprise has traditionally been separate and distinct from addiction medicine, with addiction medicine provided in the context of addiction treatment in sometimes limited ways. Public policies, practices, and laws have worked against the provision of care by physicians for the addicted. For example, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was a US federal law that regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opioids. The courts interpreted this to mean that physicians could prescribe narcotics to patients in the course of normal treatment but not for the treatment of addiction. Despite long-standing barriers to care and the risk of prosecution, physicians have recognized a need to provide care to addicted individuals. Early identification through screening for addictive disorders and brief interventions or referral to treatment is a federal initiative supported by demonstration grants from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Medications are also available for office-based treatment of alcohol and opioids. Buprenorphine and naltrexone, for example, are both FDA-approved medications used for opioid addiction. Buprenorphine is a synthetic opioid medication that acts as a partial agonist at opioid receptors—it does not produce the euphoria and sedation caused by heroin or other opioids but is able to reduce or eliminate withdrawal symptoms associated with opioid dependence and carries a low risk of overdose. Naltrexone is a synthetic opioid antagonist—it blocks opioids from binding to their receptors and thereby prevents their euphoric and other effects. Naltrexone is also used in office-based alcohol addiction treatment as it blocks opioid receptors that are involved in the rewarding effects of drinking and the craving for alcohol. Other medications used for alcohol addiction treatment are acamprosate, which acts on the gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate neurotransmitter systems and is thought to reduce symptoms of protracted withdrawal, and disulfiram, which interferes with the degradation of alcohol, resulting in the accumulation of acetalde-hyde, which, in turn, produces a very unpleasant reaction.

Brief interventions for alcohol use disorders had been studied before being adopted and expanded for substance use disorders (30). Interventions were intended to facilitate treatment of alcohol abuse in settings other than those in the addiction treatment enterprise (e.g., mental health clinics, physician’s offices) (31,32).

Brief interventions include assessment, feedback, responsibility for change, advice, and menu of options provided using empathic listening and encouraged self-efficacy (33). A more extensive review of this area is offered elsewhere in this textbook. The most critical take-home message is that this clinical approach can be used by primary care providers for their patients with harmful substance use because only a small portion of these patients warrant a clinical diagnosis of substance abuse or substance dependence.

Criminal Justice Settings for Mandated Treatment, Including Drug Courts

Research has shown that combining criminal justice sanctions with drug treatment can be effective in decreasing drug use and related crime. Individuals under legal coercion tend to stay in treatment for a longer period and do as well as or better than others not under legal pressure (34). Often, drug-addicted persons encounter the criminal justice system earlier than other health or social systems, and intervention by the criminal justice system to engage the individual in treatment may help to interrupt and shorten a career of drug use (35). Addiction treatment may be delivered before, during, after, or in lieu of incarceration.

Prison-Based Treatment Programs

Offenders with drug disorders may encounter a number of treatment options while incarcerated, including didactic drug education classes, self-help programs, and treatment based on TC or residential milieu therapy models. The TC model has been studied extensively and found to be quite effective in reducing drug use and recidivism to criminal behavior (36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree