55

CHAPTER OUTLINE

What motivates people to take action? The answer to this key question depends on what type of action is to be taken. What moves people to start therapy? What motivates them to continue therapy? What moves people to progress in therapy or to continue to progress after therapy? Answers to these questions can provide better alternatives to one of the field’s most pressing concerns: What types of therapeutic interventions would have the greatest effect on the entire population at risk for or experiencing addictive disorders?

What motivates people to change? The answer to this question depends in part on where they start. What motivates people to begin thinking about change can be different from what motivates them to begin preparing to take action. Once people are prepared, different forces can move them to take action. Once action is taken, what motivates people to maintain that action? Conversely, what causes people to regress or relapse to their addictive behaviors?

Fortunately, the answers to this complex set of questions may be simpler, or at least more systematic, than are the questions themselves. To appreciate the answers, it is helpful to begin with the author’s model of change (1–3).

THE STAGES OF CHANGE

Change is a process that unfolds over time through a series of stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination.

Precontemplation is a stage in which the individual does not intend to take action in the foreseeable future (usually measured as the next 6 months). The individual may be at this stage because he or she is uninformed or underinformed about the consequences of a given behavior. Or he or she may have tried to change a number of times and become demoralized about his or her ability to do so. Individuals in both categories tend to avoid reading, talking, or thinking about their high-risk behaviors. In other theories, such individuals are characterized as “resistant” or “unmotivated” or “not ready” for therapy or health promotion programs. In fact, traditional treatment programs were not ready for such individuals and were not motivated to match their needs.

Individuals who are in the precontemplation stage typically underestimate the benefits of change and overestimate its costs, but are unaware that they are making such mistakes. If they are not conscious of making such mistakes, it is difficult for them to change. As a result, many remain “stuck” in the precontemplation stage for years, with considerable resulting harm to their bodies, themselves, and others. There appears to be no inherent motivation for people to progress from one stage to the next. The stages are not like stages of human development, in which children have inherent motivation to progress from crawling to walking, even though crawling works very well and even though learning to walk can be painful and embarrassing. Instead, two major forces can move people to progress.

The first is developmental events. In the author’s research, the mean age of smokers who reach long-term maintenance is 39 years. Those who have passed 39 recognize it as an age to reevaluate how one has been living and whether one wants to die from that lifestyle or whether one wants to enhance the quality and quantity of the second half of life. The other naturally occurring force is environmental events. A favorite example is a couple who were both heavy smokers. Their dog of many years died of lung cancer. This death eventually moved the wife to quit smoking. The husband bought a new dog. So, even the same events can be processed differently by different people.

A common belief is that people with addictive disorders must “hit bottom” before they are motivated to change. So family, friends, and physicians wait helplessly for a crisis to occur. But how often do people turn 39 or have a dog die? When individuals show the first signs of a serious physical illness, such as cancer or cardiovascular disease, those around them usually become mobilized to help them seek early intervention. Evidence shows that early interventions often are lifesaving, and so it would not be acceptable to wait for such a patient to “hit bottom.” In opposition to such a passive stance, a third force that has been created to help patients with addictions progress beyond the precontemplation stage is called planned interventions.

Contemplation is a stage in which an individual intends to take action within the ensuing 6 months. Such a person is more aware of the benefits of changing, but also is acutely aware of the costs. When an addicted person begins to seriously contemplate giving up a favorite substance, his or her awareness of the costs of changing can increase. There is no free change. This balance between the costs and benefits of change can produce profound ambivalence, which may reflect a type of love–hate relationship with an addictive substance, and thus can keep an individual stuck at the contemplation stage for long periods of time. This phenomenon often is characterized as “chronic contemplation” or “behavioral procrastination.” Such individuals are not ready for traditional action-oriented programs.

Preparation is a stage in which an individual intends to take action in the immediate future (usually measured as the ensuing month). Such a person typically has taken some significant action within the preceding year. He or she generally has a plan of action, such as participating in a recovery group, consulting a counselor, talking to a physician, buying a self-help book, or relying on a self-change approach. It is these individuals who should be recruited for action-oriented treatment programs.

Action is a stage in which the individual has made specific, overt modifications in his or her lifestyle within the preceding 6 months. Because action is observable, behavior change often has been equated with action. But in the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), action is only one of six stages (3). In this model, not all modifications of behavior count as action. An individual must attain a criterion that scientists and professionals agree is sufficient to reduce the risk of disease. In smoking, for example, only total abstinence counts. With alcoholism and alcohol abuse, many believe that only total abstinence can be effective, whereas others accept controlled drinking as an effective action.

Maintenance is a stage in which the individual is working to prevent relapse, but does not need to apply change processes as frequently as one would in the action stage. Such a person is less tempted to relapse and is increasingly confident that he or she can sustain the changes made. Temptation and self-efficacy data suggest that maintenance lasts from 6 months to about 5 years.

One of the common reasons for early relapse is that the individual is not well prepared for the prolonged effort needed to progress to maintenance. Many persons think the worst will be over in a few weeks or a few months. If, as a result, they ease up on their efforts too early, they are at great risk of relapse.

To prepare such individuals for what is to come, they should be encouraged to think of overcoming an addiction as running a marathon rather than a sprint. They may have wanted to enter the 100th running of the Boston Marathon, but they know they would not succeed without preparation and so would not enter the race. With some preparation, they might compete for several miles but still would fail to finish the race. Only those who are well prepared could maintain their efforts mile after mile. Using the Boston Marathon metaphor, people know they have to be well prepared if they are to survive Heartbreak Hill, which runners encounter at about mile 20. What is the behavioral equivalent of Heartbreak Hill? The best evidence available suggests that most relapses occur at times of emotional distress. It is in the presence of depression, anxiety, anger, boredom, loneliness, stress, and distress that humans are at their emotional and psychological weak point.

How does the average person cope with troubling times? He or she drinks more, eats more, smokes more, and takes more drugs to cope with distress (4). It is not surprising, therefore, that persons struggling to overcome addictive disorders will be at greatest risk of relapse when they face distress without their substance of choice. Although emotional distress cannot be prevented, relapse can be prevented if patients have been prepared to cope with distress without falling back on addictive substances.

If so many Americans rely on oral consumptive behavior as a way to manage their emotions, what is the healthiest oral behavior they could use? Talking with others about one’s distress is a means of seeking support that can help prevent relapse. Another healthy alternative is exercise. Physical activity helps manage moods, stress, and distress. Also, 60 minutes per week of exercise can provide a recovering person with more than 50 health and mental health benefits (5). Exercise thus should be prescribed to all sedentary patients with addictions. A third healthy alternative is some form of deep relaxation, such as meditation, yoga, prayer, massage, or deep muscle relaxation. Letting the stress and distress drift away from one’s muscles and one’s mind helps the patient move forward at the most tempting of times.

Termination is a stage at which individuals have zero temptation and 100% self-efficacy. No matter whether they are depressed, anxious, bored, lonely, angry, or stressed, such persons are certain they will not return to their old unhealthy habits as a method of coping. It is as if they never acquired the habit in the first place. In a study of former smokers and alcoholics, fewer than 20% of each group had reached the stage of no temptation and total self-efficacy (6). Although the ideal is to be cured or totally recovered, it is important to recognize that, for many patients, a more realistic expectation is a lifetime of maintenance.

USING THE STAGES OF CHANGE MODEL TO MOTIVATE PATIENTS

The stages of change model can be applied to identify ways to motivate more patients at each phase of planned interventions for the addictions. The five phases are (i) recruitment, (ii) retention, (iii) progress, (iv) process, and (v) outcomes.

Recruitment

Too few studies have paid attention to the fact that professional treatment programs recruit or reach too few persons with addictions. Across all diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (7), fewer than 25% of persons with addictive disorders enter professional treatment in their lifetimes (8,9). With smoking, the deadliest of addictions, fewer than 10% ever participate in a professional treatment program (10).

Given that addictive disorders are among the costliest of contemporary conditions, it is crucial to motivate many more persons to participate in appropriate treatment. These conditions are costly to the addicted individuals, their families and friends, their employers, their communities, and their health care systems. Health professionals no longer can treat addictive disorders just on a case basis; instead, they must develop programs that can reach addicted persons on a population basis.

Governments and health care systems are seeking to treat addictive disorders on a population basis. But when they turn to the largest and best clinical trials of addiction therapies, they find less than completely positive outcomes (11–14). Whether the trials were conducted in work sites, schools, or entire communities, the results are remarkably similar: No significant effects compared with the control conditions.

If we examine more closely one of these trials, the Minnesota Heart Health Study, we can find hints of what went wrong (15). With smoking as one of the targeted behaviors, nearly 90% of the smokers in treated communities reported seeing media stories about smoking, but the same was true with smokers in the control communities. Only about 12% of smokers in the treatment and control conditions said their physicians talked to them about smoking in the preceding year. If one looks at what percentage participated in the most powerful behavior change programs (clinics, classes, and counselors), it is apparent that only 4% of smokers participated in each year of planned interventions. Even when state-of-the-science smoking cessation clinics are offered at no charge, only 1% of smokers are recruited (16). There simply will be little effect on the health of the nation if our best treatment programs reach so few persons with the deadliest of addictions.

How can more people with addictive disorders be motivated to seek the appropriate help? By changing both paradigms and practices. There are two paradigms that need to be changed. The first is an action-oriented paradigm that construes behavior change as an event that can occur quickly, immediately, discretely, and dramatically. Treatment programs that are designed to have patients immediately quit abusing substances are implicitly or explicitly designed for the portion of the population in the preparation stage.

The problem is that, with most unhealthy behaviors, fewer than 20% of the affected population is prepared to take action. Among smokers in the United States, for example, about 40% are in the precontemplation stage, 40% in the contemplation stage, and 20% in the preparation stage (17). Among college students who abuse alcohol, about 85% are in the precontemplation stage, 10% in the contemplation stage, and 5% in the preparation stage (18).

When only action-oriented interventions are offered, fewer than 20% of the at-risk population is being recruited. To meet the needs of the entire addicted population, interventions must meet the needs of the 40% in the precontemplation and the 40% in the contemplation stages.

In the clinical guidelines for the treatment of tobacco, however, there were only evidence-based programs for motivated smokers in the preparation stage (19). In spite of there being more than 6,000 studies on tobacco, research had excluded the vast majority from treatment studies.

By offering stage-matched interventions and applying proactive or outreach recruitment methods in three large-scale clinical trials, the author and others have been able to motivate 80% to 90% of smokers to enter a treatment program (20,21). Comparable participation rates were generated with college students who abuse alcohol, even though 75% were in the precontemplation stage (18). These results represent a quantum increase in our ability to move many more people to take the action of starting therapy.

A treatment program for addicted gamblers in Windsor, Ontario, used creative communications to let their prospective population know, wherever they are, the program can work with them. This program had generous support of 2% of earnings from local casinos, but they were not reaching many people. So, on the back of city buses, they placed ads with a traffic light logo: red light not ready, yellow light getting ready, and green light ready. Not only did they dramatically increase their recruitment, some clients would take pride in saying, “Hey, there goes my bus!”

The second paradigm change that is required is movement from a passive–reactive approach to a proactive approach. Most professionals have been trained to be passive–reactive: to passively wait for patients to seek their services and then to react. The problem with this approach is that most persons with addictive disorders never seek such services.

The passive–reactive paradigm is designed to serve populations with acute conditions. The pain, distress, or discomfort of such conditions can motivate patients to seek the services of health professionals. But the major killers today are chronic lifestyle disorders such as the addictions. To treat the addictions seriously, professionals must learn how to reach out to entire populations and offer them stage-matched treatments.

There are a growing number of national disease management and disease prevention companies who train health professionals in these new paradigms. Thousands of nurses, counselors, and health coaches have been trained to proactively reach out by telephone to interact at each stage of change with entire patient and employee populations with high-risk behaviors including smoking, alcohol abuse, and obesity. With the major movement toward integrated care in patient-centered medical homes, providers on multidisciplinary teams are being trained in how to deliver such stage-based interventions within primary care settings.

What happens if professionals change only one paradigm and proactively recruit entire populations to action-oriented interventions? This experiment has been tried in one of the largest US managed care organizations (16). Physicians spent time with every smoker in an effort to persuade him or her to enroll in a state-of-the-art action-oriented clinic. If that did not work, nurses spent up to 10 minutes encouraging the smoker to enroll, followed by 12 minutes with a health educator and a counselor call to the home. The base rate was 1% participation.

This most intensive recruitment protocol motivated 35% of smokers in precontemplation to enroll. However, only 3% actually entered the program, 2% completed it, and none showed improved outcomes. From a combined contemplation and preparation group, 65% enrolled, 15% entered the program, 11% completed it, and some had an improved outcome.

In the face of this evidence, there may be several answers to the question: What can move a majority of people to enter a professional treatment program for an addictive disorder? One is the availability of professionals who are motivated and prepared to proactively reach out to entire populations and offer them interventions that match whatever stage of change they are in.

Retention

What motivates patients to continue in therapy? Or conversely, what moves clients to terminate counseling quickly and prematurely, as judged by their counselors? A meta-analysis of 125 studies found that nearly 50% of clients drop out of treatment (22). Across studies, there were few consistent predictors of premature termination. Although addictive disorder, minority status, and lower education predicted a higher percentage of dropouts, these variables did not account for much of the variance.

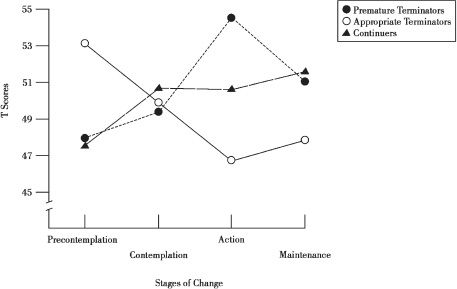

At least five studies are available on dropouts from a stage model perspective on addictive disorder, smoking, obesity, and a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders. These studies found that stage-related variables were more reliable predictors than demographics, type of problem, severity of problem, and other problem-related variables. Figure 55-1 presents the stage profiles of three groups of patients with a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders (2,23). In that study, the investigators were able to predict 93% of the three groups: premature terminators, early but appropriate terminators, and those who continued in therapy (23).

FIGURE 55-1 Pretherapy stage profiles for premature terminators, appropriate terminators, and continuers. (From Brogan ME, Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM. Predicting termination and continuation status in psychotherapy using the transtheoretical model. Psychotherapy 1999;36:105–113.)

Figure 55-1 shows that the before-therapy profile of the entire group who dropped out quickly and prematurely (40%) was a profile of persons in the precontemplation stage. The 20% who finished quickly but appropriately had a profile of patients who were in the action stage at the time they entered therapy. Those who continued in long-term treatment were a mixed group, with most in the contemplation stage.

The lesson is clear: Persons in the precontemplation stage cannot be treated as if they are starting in the same place as those in the action stage. If they are pressured to take action when they are not prepared, they simply will leave therapy.

For patients in the action stage who enter therapy, what would be an appropriate approach? One alternative would be to provide relapse prevention strategies like those described by Dr. Alan Marlatt. But would relapse prevention strategies make any sense with the 40% of patients who enter in the precontemplation stage? What might be a good match for them? Experience suggests a dropout prevention approach, because such patients are likely to leave early if they are not helped to continue.

With patients who begin therapy in the precontemplation stage, it is useful for the therapist to share key concerns: “I’m concerned that therapy may not have a chance to make a significant difference in your life, because you may be tempted to leave early.” The therapist then can explore whether the patient has been pressured to enter therapy. How do such patients react when someone tries to pressure or coerce them into quitting an addiction when they are not ready? Can they tell the therapist if they feel pressured or coerced? It is only feasible to encourage them to take steps when they are most ready to succeed.

Here is a brief case illustration of a therapist sharing his concern with a patient in precontemplation.

A renowned artist in his late thirties started therapy with multiple problems, including a chronic addiction to cocaine, a troubled marriage, career at risk of collapsing, and affective problems with depression and aggression. With his help, we are able to assess that he was in the precontemplation stage, and his therapist knew that he was at high risk for terminating treatment prematurely. So, the therapist shared his concern: “I appreciate your helping me to understand that you are currently in the initial stage of change that we call precontemplation. Our first concern needs to be that you might drop out of treatment before we have a chance to make a significant difference in your life. What pressures were there for you to come to therapy?” “My wife threatened to leave if I didn’t show up,” he responded. “If you feel me pressuring you to do something you are not ready to do, would you let me know?” the therapist asked. “You will know!” he snapped. “How will I know?” “Because I will get angry as hell!” the patient said. “That’s O.K. I can work with that. What I can’t work with is you not coming back.” “That’s cool,” he said.

The author and others have conducted four studies with stage-matched interventions in which retention rates of persons entering interventions in the precontemplation stage can be examined. What is clear is that, when treatment is matched to stage, persons in the precontemplation stage will remain in treatment at the same rates as those who start in the preparation stage (19,20). This result was consistent in clinical trials in which patients were recruited proactively (the therapist reached out with an offer of help) as well as in trials in which patients were recruited reactively (they asked for help). What motivates people to continue in therapy? Receiving treatments that match their stage of readiness to change.

Another strategy is to begin therapy with a single session of motivational interviewing. Connors et al. (24) found that a single session reduced dropouts from their intensive alcohol treatment program from 75% to 50%. A session of role induction designed to prepare people for what to expect from therapy made no difference, even though, clinically, it has been most widely used to try to prevent premature dropout.

Progress

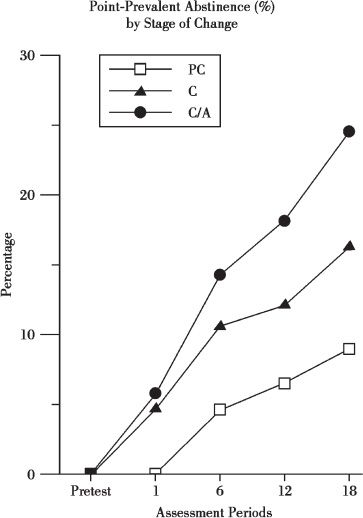

What moves people to progress in therapy and to continue to progress after therapy? Figure 55-2 presents an example of what is called the stage effect. The stage effect predicts that the amount of successful action taken during and after treatment is directly related to the stage at which the person entered treatment (2). In the study cited, interventions with smokers ended at 6 months. The group of smokers who started in the precontemplation stage showed the least amount of effective action, as measured by abstinence at each assessment point. Those who started in the contemplation stage made significantly more progress, whereas those who entered treatment already prepared to take action were most successful at every assessment.

FIGURE 55-2 Percentage of smokers who maintained abstinence over 18 months. Note: Groups were in the following stages at the time of entry into treatment: precontemplation (PC), contemplation (C), and preparation (C/A) (n = 570).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree