The Superficial Front Line

Overview

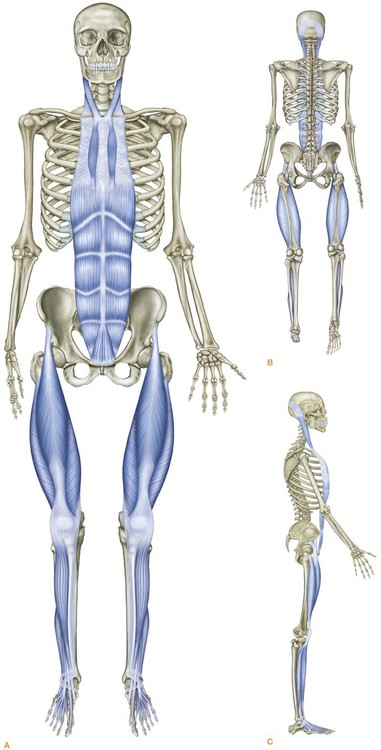

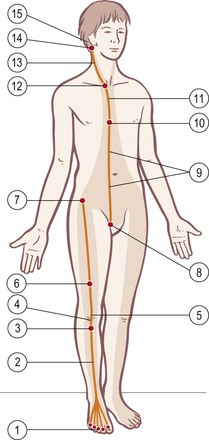

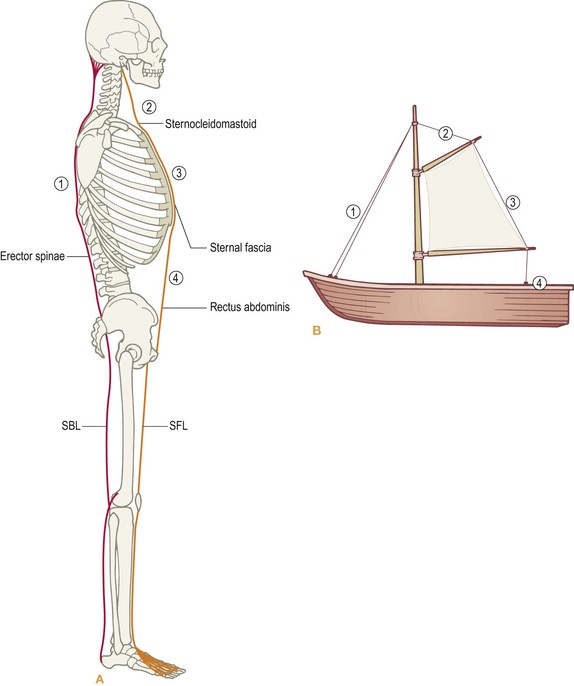

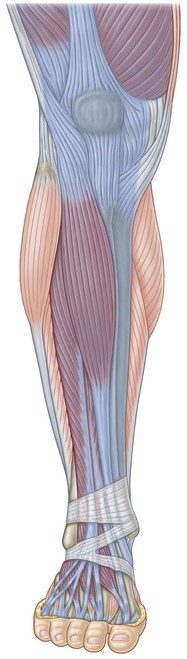

The Superficial Front Line (SFL) (Fig. 4.1) connects the entire anterior surface of the body from the top of the feet to the side of the skull in two pieces – toes to pelvis and pelvis to head (Fig. 4.2/Table 4.1) – which, when the hip is extended as in standing, function as one continuous line of integrated myofascia.

Table 4.1

Superficial Front Line: myofascial ‘tracks’ and bony ‘stations’ (Fig. 4.2)

| Bony stations | Myofascial tracks | |

| 15 | Scalp fascia | |

| Mastoid process | 14 | |

| 13 | Sternocleidomastoid | |

| Sternal manubrium | 12 | |

| 11 | Sternalis/sternochondral fascia | |

| 5th rib | 10 | |

| 9 | Rectus abdominis | |

| Pubic tubercle | 8 | |

| Anterior inferior iliac spine | 7 | |

| 6 | Rectus femoris/quadriceps | |

| Patella | 5 | |

| 4 | Subpatellar tendon | |

| Tibial tuberosity | 3 | |

| 2 | Short and long toe extensors, tibialis anterior, anterior crural compartment | |

| Dorsal surface of toe phalanges | 1 |

Fig. 4.2 Superficial Front Line tracks and stations. The shaded area shows the area of superficial fascial influence.

Postural function

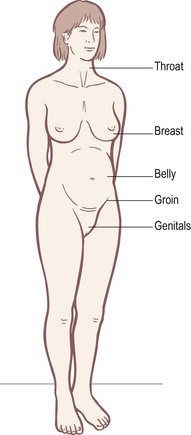

The overall postural function of the SFL is to balance the Superficial Back Line (SBL), and to provide tensile support from the top to lift those parts of the skeleton which extend forward of the gravity line – the pubis, rib cage, and face. Myofascia of the SFL also maintain the postural extension of the knee. The muscles of the SFL stand ready to defend the soft and sensitive parts that adorn the front surface of the human body, and protect the viscera of the ventral cavity (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3 Human beings have developed a unique way of standing which presents all their most sensitive and vulnerable areas to the oncoming world, all arrayed along the SFL. Compare this to quadrupeds, who protect most or all of these vulnerable areas (see Fig. 4.31).

Sagittal postural balance (A–P balance) is primarily maintained throughout the body by either an easy or a tense relationship between these two lines (Fig. 4.4). In the trunk and neck, however, the Deep Front Line must be included to complete and complicate the equation (see Fig. 3.36 and Ch. 9).

Fig. 4.4 The SBL and the SFL have a reciprocal relationship, not unlike the rigging of a sailboat. The SBL is designed to pull down the back from the bottom to the top, and the SFL is designed to pull up the front from neck to pelvis. (Based on Mollier.1)

When the lines are considered as parts of fascial planes, rather than as chains of contractile muscles, it is worth noting that in by far the majority of cases, the SFL tends to shift down, and the SBL tends to shift up in response (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5 It is a very common pattern for the SFL to be pulled down the front while the SBL hikes up the back (vertical lines). This creates a disparity between the corresponding structures in the front and the back of the body (horizontal lines). This is the foundation for a host of future problems for the neck, the arms, breathing, or the lower back.

Movement function

The overall movement function of the SFL is to create flexion of the trunk and hips, extension at the knee, and dorsiflexion of the foot (Fig. 4.6). The SFL performs a complex set of actions at the neck level, which comes up for discussion below. The need to create sudden and strong flexion movements at the various joints requires that the muscular portion of the SFL contain a higher proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibers. The interplay between the predominantly endurance-oriented SBL and the quickly reactive SFL can be seen in the need for contraction in one line when the other is stretched (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.6 Contraction of the SFL extends the toes, dorsiflexes the ankles, extends the knees, and flexes the hips and trunk – but also, as here, hyperextends the upper neck.

Fig. 4.7 The reciprocal relationship between the SBL and SFL can be seen in these two poses. In (A), the SBL is contracted and the SFL stretched, vice versa in (B).

The Superficial Front Line in detail

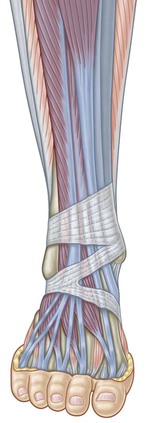

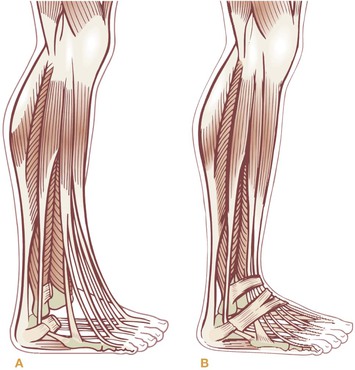

![]() The tendons that originate on the top of the toes form the beginning of the SFL. Moving up the foot, the SFL picks up two additional tendons (Fig. 4.8). On the lateral side, we get the peroneus (fibularis) tertius (if there is one) originating from the 5th metatarsal. From the medial side, we find the tendon of the tibialis anterior from the 1st metatarsal on the medial side of the foot. The SFL thus includes both the short extensor muscles on the dorsum of the foot and the long tendons from the lower leg.

The tendons that originate on the top of the toes form the beginning of the SFL. Moving up the foot, the SFL picks up two additional tendons (Fig. 4.8). On the lateral side, we get the peroneus (fibularis) tertius (if there is one) originating from the 5th metatarsal. From the medial side, we find the tendon of the tibialis anterior from the 1st metatarsal on the medial side of the foot. The SFL thus includes both the short extensor muscles on the dorsum of the foot and the long tendons from the lower leg.

The shin

The fascial plane of the SFL passes up into the anterior compartment of the lower leg, but on its way it passes under the extensor retinaculum. The retinaculum is essentially a thickening of an even more superficial fascial plane, the deep investing crural fascia that surrounds the lower leg. This retinacular thickening is necessary to hold the tendons down (otherwise your skin between the foot and the middle of the shin would pop out every time the muscles contracted – Fig. 4.9). Because the tendons run around a corner (allowed by our rules in this case because of the clear fascial and mechanical continuity), lubricating tissues wrap around the tendons to ease their movement under the retinacular strap.

Fig. 4.9 The retinacula, thickenings in the deep investing crural fascia, provide a pulley to hold in the tendons of the SFL and direct their force from the shin muscle to the toes.

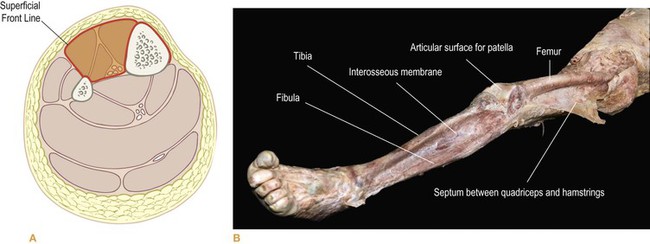

Above the retinaculum, the SFL passes up the front of the lower leg. On the lateral side, it contains the muscles of the anterior compartment – the tibialis anterior and the extensor digitorum and hallucis longus – in the scooped-out shape anterior to the interosseous membrane. On the medial side, we have found that, for best effect, the crural fascia must also be included where it overlies the tibia and its periosteum (compare Fig. 4.10 to Fig. 2.1C, p. 66).

Fig. 4.10 The SFL occupies the anterior compartment of the leg, and the tissues on the front of the tibia (shinbone) as well. In (B), we see how little of the leg is left when the SFL is removed. See also Figure 2.1C, where both these parts of the crural fascia have been dissected as one piece – the anterior compartment and the surface fascia coating the tibia. Where holes appear in this fascia are probably places where the person suffered trauma to the shin (as in falling upstairs), resulting in the crural fascia adhering to the periosteum underneath. (DVD ref: Anatomy Trains Revealed) ![]()

The anterior crural compartment

Have your client supine, with the heels just off the end of the table. Have her dorsiflex and plantarflex, checking to see that she is ‘tracking’ straight with the ankle, so that the foot is headed directly toward the knee, not up and in or up and out. You can add more muscular differentiation by adding toe flexion and extension to the ankle movement.

When your work does extend above the ankle, pay attention to which side of the shin is more restricted – the medial or the lateral. Since you began on the tendons, the natural progression is up onto the muscles of the anterior compartment, on the lateral side of the anterior shin. The SFL, however, also includes the periosteum and superficial fascial layers that pass over the tibia on the anteromedial side (see Figs 2.1C, 4.10 and 4.11).

Fig. 4.11 The top of the anterior compartment leads past the tibial tuberosity onto the subpatellar tendon and the quadriceps complex.

We have arrived at the second common pattern problem in this area, so let us define the problem before we finish with the technique. In any kind of forward lean of the legs, where the knee rests posturally on a line anterior to the ankle, the posterior calf muscles tighten (eccentrically loaded in the muscle and locked long in the fascia), and the anterior muscles and tissue move down (and tighten concentrically, locking the fascia short). One of the best remedies for this is to move the tissue of the anterior surface up again (while the corresponding tissues of the SBL are moved down).

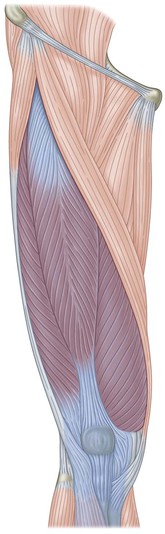

The thigh

![]() Although the muscles themselves have attachments within the anterior compartment to the tibia, fibula, and interosseous membrane, the next station for the SFL is at the top of both the medial and lateral side of this track, the tibial tuberosity (Fig. 4.11).

Although the muscles themselves have attachments within the anterior compartment to the tibia, fibula, and interosseous membrane, the next station for the SFL is at the top of both the medial and lateral side of this track, the tibial tuberosity (Fig. 4.11).

The three vastii of the quadriceps all grab onto various parts of the femoral shaft, but the fourth head, the rectus femoris, continues bravely upward, carrying the SFL to the pelvis (Fig. 4.12). Although the rectus occupies the anterior surface of the thigh, its proximal attachment is not so superficial. Its upper end dives beneath the tensor fasciae latae and the sartorius to attach to the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS), a little bit below and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). There is a small but important head of the rectus that wraps around the top of the hip joint. Palpation and experience with dissection reveals that in some undetermined percentage of the population there is an additional fascial attachment of this muscle to the ASIS.