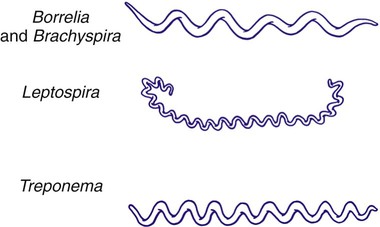

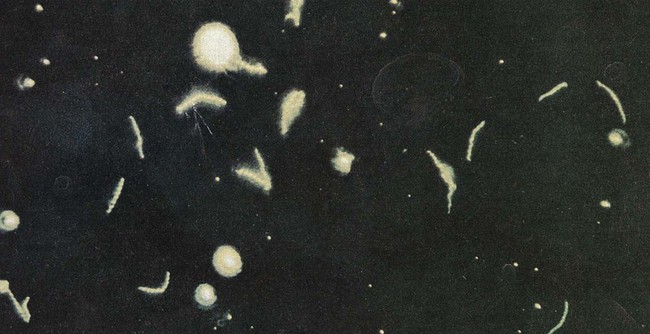

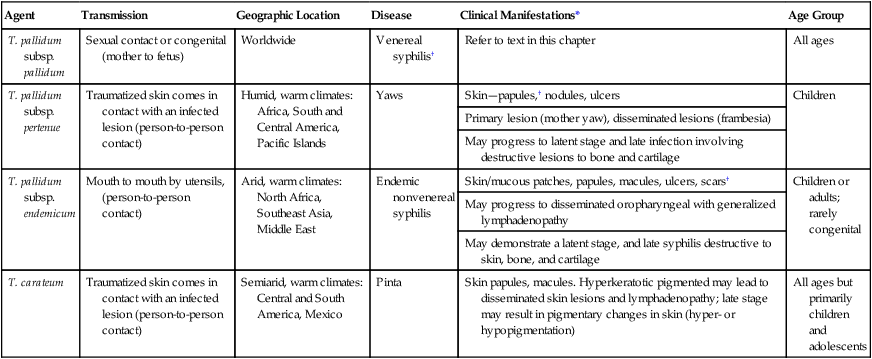

1. Describe the bacterial agents discussed in this chapter in terms of morphology, taxonomy, and growth conditions. 2. Identify the four stages of syphilis (i.e., primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary) according to clinical symptoms, antibody production, transmission, and infectivity. 3. Explain congenital syphilis, including transmission and clinical manifestations. 4. Define reagin, cardiolipin, and biologic false positive. 5. Differentiate reagin and treponemal antibodies, including specificity and association with disease. 6. Identify the various serologic methods that utilize specific treponemal or nonspecific nontreponemal antigens. 7. Describe the basic principles for the RPR, VDRL, FTA-ABS, TP-PA, and MHA-TP assays. 8. Compare Borrelia spp. to the other spirochetes discussed in this chapter, including morphology and growth conditions. 9. Describe the pathogenesis for relapsing fever and Lyme disease, including the routes of transmission, vector, and disease presentation. 10. Explain the methodology and clinical significance for using a two-step diagnostic procedure for Borrelia spp. infections. 11. Describe the pathogenesis associated with leptospirosis, including the two major stages of the disease and the recommended clinical specimens. 12. Describe Brachyspira spp., including potential pathogenesis, appropriate specimen, transmission, and clinical significance. 13. Correlate patient signs and symptoms with laboratory data to identify the most likely etiologic agent. The spirochetes are all long, slender, helically curved, gram-negative bacilli, with the unusual morphologic features of axial fibrils and an outer sheath. These fibrils, or axial filaments, are flagella-like organelles that wrap around the bacteria’s cell walls, are enclosed within the outer sheath, and facilitate motility of the organisms. The fibrils are attached within the cell wall by platelike structures, called insertion disks, located near the ends of the cells. The protoplasmic cylinder gyrates around the fibrils, causing bacterial movement to appear as a corkscrew-like winding. Differentiation of genera within the family Spirochaetaceae is based on the number of axial fibrils, the number of insertion disks present (Table 46-1), and biochemical and metabolic features. The spirochetes also fall into genera based loosely on their morphology (Figure 46-1): Treponema appear as slender with tight coils; Borrelia are somewhat thicker with fewer and looser coils; and Leptospira resemble Borrelia except for their hooked ends. Brachyspira are comma-shaped or helical, with tapered ends with four flagella at each end. TABLE 46-1 Spirochetes Pathogenic for Humans Key features of the epidemiology of diseases caused by the pathogenic treponemes are summarized in Table 46-2. In general, these organisms enter the host by either penetrating intact mucous membranes (as is the case for T. pallidum subsp. pallidum—hereafter referred to as T. pallidum) or entering through breaks in the skin. T. pallidum is transmitted by sexual contact and vertically from mother to the unborn fetus. After penetration, T. pallidum subsequently invades the bloodstream and spreads to other body sites. Although the mechanisms by which damage is done to the host are unclear, T. pallidum has a remarkable tropism (attraction) to arterioles; infection ultimately leads to endarteritis (inflammation of the lining of arteries) and subsequent progressive tissue destruction. TABLE 46-2 Epidemiology and Spectrum of Disease of the Treponemes Pathogenic for Humans *All diseases have a relapsing clinical course and prominent cutaneous manifestations. †If untreated, organisms can disseminate to other parts of the body such as bone. The additional pathogenic treponemes are major health concerns in developing countries. Although morphologically and antigenically similar, these agents differ epidemiologically and with respect to their clinical presentation from T. pallidum. The diseases caused by these treponemes are summarized in Table 46-2. Material for dark-field examination is examined immediately under 400× high-dry magnification for the presence of motile spirochetes. Treponemes are long (8 to 10 µm, slightly larger than a red blood cell) and consist of 8 to 14 tightly coiled, even spirals (Figure 46-2). Once seen, characteristic forms should be verified by examination under oil immersion magnification (1000×). Although the darkfield examination depends greatly on technical expertise and the numbers of organisms in the lesion, it can be highly specific when performed on genital lesions. The two most widely used nontreponemal serologic tests are the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests. Each of these tests is a flocculation (or agglutination) test, in which soluble antigen particles are coalesced to form larger particles that are visible as clumps when they are aggregated in the presence of antibody. The VDRL is used as a quantitative test and may be performed on serum or CSF in suspected cases of neurosyphilis. See Procedures 46-1 and 46-2 on the Evolve site for details and limitations for the VDRL and RPR.

The Spirochetes

Genus

Axial Filaments

Insertion Disks

Treponema

6 to 10

1

Borrelia

30 to 40

2

Leptospira

2

3 to 5

Treponema

General Characteristics

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Agent

Transmission

Geographic Location

Disease

Clinical Manifestations*

Age Group

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum

Sexual contact or congenital (mother to fetus)

Worldwide

Venereal syphilis†

Refer to text in this chapter

All ages

T. pallidum subsp. pertenue

Traumatized skin comes in contact with an infected lesion (person-to-person contact)

Humid, warm climates: Africa, South and Central America, Pacific Islands

Yaws

Skin—papules,† nodules, ulcers

Children

Primary lesion (mother yaw), disseminated lesions (frambesia)

May progress to latent stage and late infection involving destructive lesions to bone and cartilage

T. pallidum subsp. endemicum

Mouth to mouth by utensils, (person-to-person contact)

Arid, warm climates: North Africa, Southeast Asia, Middle East

Endemic nonvenereal syphilis

Skin/mucous patches, papules, macules, ulcers, scars†

Children or adults; rarely congenital

May progress to disseminated oropharyngeal with generalized lymphadenopathy

May demonstrate a latent stage, and late syphilis destructive to skin, bone, and cartilage

T. carateum

Traumatized skin comes in contact with an infected lesion (person-to-person contact)

Semiarid, warm climates: Central and South America, Mexico

Pinta

Skin papules, macules. Hyperkeratotic pigmented may lead to disseminated skin lesions and lymphadenopathy; late stage may result in pigmentary changes in skin (hyper- or hypopigmentation)

All ages but primarily children and adolescents

Spectrum of Disease

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection

Direct Detection

Serodiagnosis