Chapter 21 The special senses

Disorders of the ear, nose and throat

The Ear

Anatomy and physiology

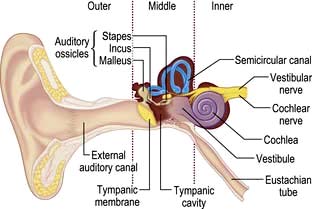

The ear can be divided into three parts: outer, middle and inner (Fig. 21.1).

The inner ear contains the cochlea for hearing and the vestibule and semicircular canals for balance. There is a semicircular canal arranged in each body plane and these are stimulated by rotatory movement. The facial, cochlear and vestibular nerves emerge from the inner ear and run through the internal acoustic meatus to the brainstem (see Fig. 22.7, p. 1076).

Common disorders

The discharging ear (otorrhoea)

Discharge from the ear is usually due to infection of the outer or middle ear.

Hearing loss

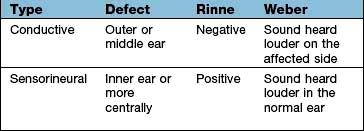

Deafness can be conductive or sensorineural and these can be differentiated at the bedside by the Rinne and the Weber tests (Box 21.1) or with pure-tone audiometry. Conductive hearing loss has many causes (Table 21.1) but wax is the commonest.

| Conductive | Sensorineural |

|---|---|

External meatus | Congenital |

WaxForeign bodyOtitis externaChronic suppurationDrum | Pendred’s syndrome (see p. 962) |

Long QT syndrome | |

Björnstad’s syndrome (pili torti) | |

End organ | |

Advancing ageOccupational acoustic traumaMénière’s diseaseDrugs (e.g. gentamicin, furosemide) | |

Perforation/trauma | |

Middle ear | |

Otosclerosis | |

Eighth nerve lesions | |

Acoustic neuroma | |

| Cranial trauma |

| Inflammatory lesions: |

| Tuberculous meningitis |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Neurosyphilis |

| Carcinomatous meningitis |

| Brainstem lesions (rare) |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Infarction |

Normally a tuning fork, 512 Hz, will be heard as louder if held next to the ear (i.e. air conduction) than it will if placed on the mastoid bone (Rinne positive).

Normally a tuning fork, 512 Hz, will be heard as louder if held next to the ear (i.e. air conduction) than it will if placed on the mastoid bone (Rinne positive).

If the tuning fork is perceived louder when placed on the mastoid (i.e. via bone conduction), then a defect in the conducting mechanism of the external or middle ear is present (true Rinne negative).

If the tuning fork is perceived louder when placed on the mastoid (i.e. via bone conduction), then a defect in the conducting mechanism of the external or middle ear is present (true Rinne negative).

Presbycusis

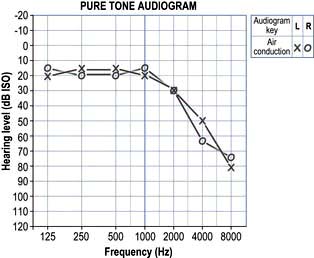

This is the commonest cause of deafness. It is a degenerative disorder of the cochlea and is typically seen in old age. It can be due to the loss of outer hair cells (sensory), loss of the ganglion cells (neural), strial atrophy (metabolic) or it can be a mixed picture. Ageing itself does not cause outer hair cell loss but environmental noise toxicity over the years is a major factor. The onset is gradual and the higher frequencies are affected most (Fig. 21.2). Speech has two components: low frequencies (vowels) and high frequencies (consonants). When the consonants are lost, speech loses its intelligibility. Increasing the volume merely increases the low frequencies and the characteristic response of ‘Don’t shout. I’m not deaf!’

Noise trauma

Cochlear damage can occur, e.g. when shooting without ear protectors or from industrial noise (see p. 935), and characteristically has a loss at 4 kHz.

Acoustic neuroma

This is a slow-growing benign schwannoma of the vestibular nerve (see p. 1076) which can present with progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Any patient with an asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss or sudden sensorineural hearing loss should be investigated, e.g. with an MRI scan.

Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

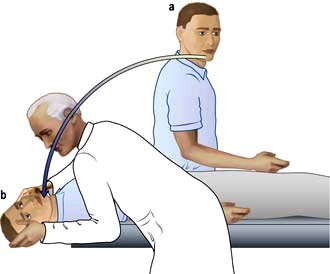

BPPV is thought to be due to loose otoliths in the semicircular canals, commonly the posterior canal. Positional vertigo is precipitated by head movements, usually to a particular position, and often occurs when turning in bed or on sitting up. The onset is typically sudden and distressing. The vertigo lasts seconds or minutes and the phenomenon becomes less severe on repeated movements (fatigue). There is no serious underlying cause but it sometimes follows vestibular neuronitis (see p. 1079), head injury or ear infection.

Diagnosis is made on the basis of the history and by the Hallpike manoeuvre (Fig 21.3). A positive Hallpike test confirms BPPV, which can be cured in over 90% of cases by the Epley manoeuvre. This involves gentle but specific manipulation and rotation of the patient’s head to shift the loose otoliths from the semicircular canals.

The nose

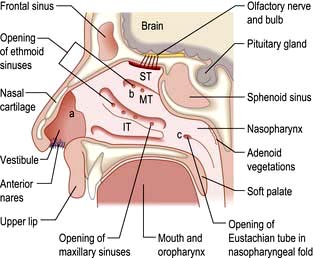

Anatomy and physiology (Fig. 21.4)

The function of the nose is to facilitate smell and respiration:

Smell is a sensation conveyed by the olfactory epithelium in the roof of the nose. The olfactory epithelium is supplied by the first cranial nerve (see p. 1071).

Smell is a sensation conveyed by the olfactory epithelium in the roof of the nose. The olfactory epithelium is supplied by the first cranial nerve (see p. 1071).

The nose also filters, moistens and warms inspired air and in doing so assists the normal process of respiration.

The nose also filters, moistens and warms inspired air and in doing so assists the normal process of respiration.

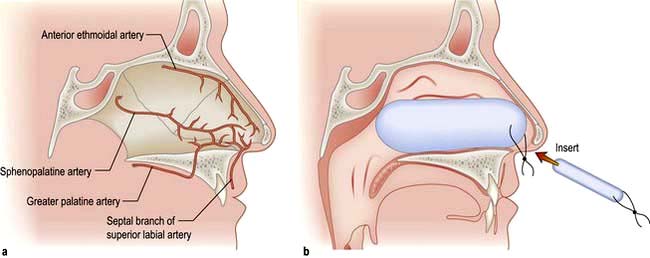

The blood supply of the nose is derived from branches of both the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid artery supplies the upper nose via the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. The external carotid artery supplies the posterior and inferior portion of the nose via the superior labial artery, greater palatine artery and sphenopalatine artery. On the anterior nasal septum is an area of confluence of these vessels (Little’s area) (Fig. 21.5a).

Common disorders

Epistaxis

Nose bleeds vary in severity from minor to life-threatening. Little’s area (Fig. 21.5a) is a frequent site of nasal haemorrhage. First aid measures should be administered immediately, including external digital compression of the anterior lower portion of the external nose, ice packs and leaning forward. The patient should be asked to avoid swallowing any blood running posteriorly as this causes gastric irritation and then nausea and vomiting.

Not infrequently, small recurrent epistaxes occur and these may require a visit to the emergency clinic for an examination and simple local anaesthetic cautery with a silver nitrate stick. If the bleeding continues profusely then resuscitation in the form of intravenous access, fluid replacement or blood, and oxygen can be administered. If further intervention is necessary, consideration should be given to intranasal cautery of the bleeding vessel, or intranasal packing using a variety of commercially available nasal packs (Fig. 21.5b). In addition to direct treatment of the epistaxis, a cause and appropriate treatment of a cause should be sought (Table 21.2).

Table 21.2 Aetiology of epistaxis

Local | Idiopathic |

Trauma – foreign bodies, nose-picking and nasal fractures | |

Iatrogenic – surgery, intranasal steroids | |

Neoplasm – nasal, paranasal sinus and nasopharyngeal tumours | |

General | Anticoagulants |

Coagulation disorders | |

Hypertension | |

Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome (familial haemorrhagic telangiectasia) |

Nasal obstruction

Rhinitis (see p. 808). If an allergen is identified, then allergen avoidance is the mainstay of treatment. Topical steroids and/or antihistamines can be tried. If severe, then oral antihistamines or referral to an allergy clinic for immunotherapy is warranted.

Rhinitis (see p. 808). If an allergen is identified, then allergen avoidance is the mainstay of treatment. Topical steroids and/or antihistamines can be tried. If severe, then oral antihistamines or referral to an allergy clinic for immunotherapy is warranted.

Septal deviation. Correction of this deviation can be undertaken surgically.

Septal deviation. Correction of this deviation can be undertaken surgically.

Nasal polyps. This condition occurs with inflammation and oedema of the sinus nasal mucosa. This oedematous mucosa prolapses into the nasal cavity and can cause significant nasal obstruction. In allergic rhinitis (see p. 798) the mucosa lining the nasal septum and inferior turbinates are swollen and a dark red or plum colour. Nasal polyps can be identified as glistening swellings which are not tender. Treatment with intranasal steroids helps but if polyps are large or unresponsive to medical treatment then surgery is necessary.

Nasal polyps. This condition occurs with inflammation and oedema of the sinus nasal mucosa. This oedematous mucosa prolapses into the nasal cavity and can cause significant nasal obstruction. In allergic rhinitis (see p. 798) the mucosa lining the nasal septum and inferior turbinates are swollen and a dark red or plum colour. Nasal polyps can be identified as glistening swellings which are not tender. Treatment with intranasal steroids helps but if polyps are large or unresponsive to medical treatment then surgery is necessary.

Foreign bodies. These are usually seen in children who present with unilateral nasal discharge. Clinical examination of the nose with a light source often reveals the foreign body, which requires removal either in clinic or in theatre with a general anaesthetic.

Foreign bodies. These are usually seen in children who present with unilateral nasal discharge. Clinical examination of the nose with a light source often reveals the foreign body, which requires removal either in clinic or in theatre with a general anaesthetic.

Sinonasal malignancy. This is extremely rare. The diagnosis must be considered if unusual unilateral symptoms are seen, including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain, epiphora, cheek swelling, paraesthesia of the cheek and proptosis of the orbit.

Sinonasal malignancy. This is extremely rare. The diagnosis must be considered if unusual unilateral symptoms are seen, including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain, epiphora, cheek swelling, paraesthesia of the cheek and proptosis of the orbit.

Sinusitis

If the symptoms of sinusitis are recurrent (Box 21.2) or complications such as orbital cellulitis arise, then an ENT opinion is appropriate and a CT scan of the paranasal sinuses is undertaken. Plain sinus X-rays are now rarely used to image the sinuses.

![]() Box 21.2

Box 21.2

Types of sinusitis

Acute | Symptoms lasting 1 week to 1 month |

Recurrent acute | >4 episodes of acute sinusitis per year |

Subacute | Symptoms for 1–3 months |

Chronic | Symptoms for >3 months |

CT scan of the sinuses or an MRI scan can demonstrate bony landmarks and soft tissue planes.

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is used for ventilation and drainage of the sinuses.

Anosmia

A conductive deficit of smell occurs if odorant molecules do not reach the olfactory epithelium high in the nose.

A conductive deficit of smell occurs if odorant molecules do not reach the olfactory epithelium high in the nose.

A sensorineural loss of smell is incurred if the neural transmission of smell is affected.

A sensorineural loss of smell is incurred if the neural transmission of smell is affected.

Some conditions predispose to a mixed (conductive and sensorineural) loss of smell.

Some conditions predispose to a mixed (conductive and sensorineural) loss of smell.

The throat

Anatomy and physiology

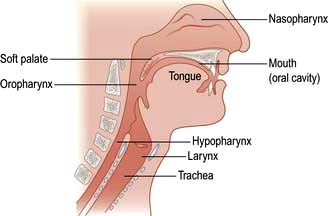

The throat can be considered as the oral cavity, the pharynx and the larynx (Fig. 21.6). The oral cavity extends from the lips to the tonsils. The pharynx can be divided into three areas:

The nasopharynx: extending from the posterior nasal openings to the soft palate

The nasopharynx: extending from the posterior nasal openings to the soft palate

The oropharynx: extending from the soft palate to the tip of the epiglottis

The oropharynx: extending from the soft palate to the tip of the epiglottis

The hypopharynx: extending from the tip of the epiglottis to just below the level of the cricoid cartilage where it is continuous with the oesophagus.

The hypopharynx: extending from the tip of the epiglottis to just below the level of the cricoid cartilage where it is continuous with the oesophagus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree