CHAPTER 8 The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx

This chapter begins with a discussion of the bony sacrum. Then, because of its clinical significance, the sacroiliac joint is covered in detail. This is followed by a discussion of the anatomy of the coccyx.

THE SACRUM

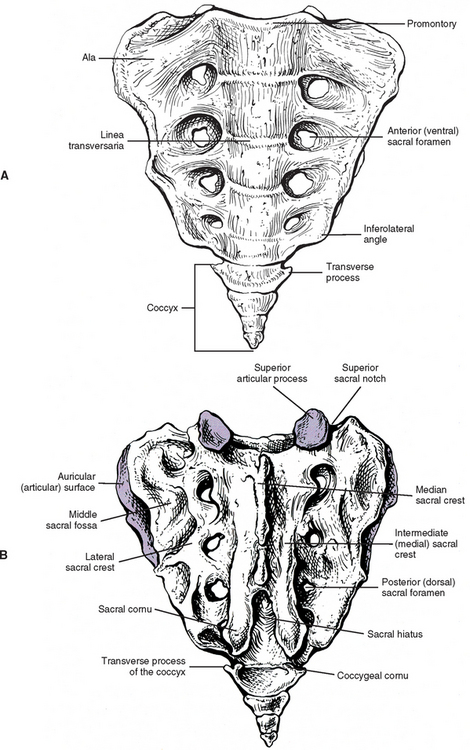

The sacrum is composed of five fused vertebral segments. The sacral segments decrease in size from the first to the fifth, making the sacrum triangular in shape. Consequently, the wider superior surface of the sacrum is known as the sacral base, and the smaller inferior surface is known as the apex (Figs. 8-1 and 8-2). The sacrum is concave anteriorly (kyphotic), and as with the other primary kyphosis (the thoracic region), its curvature helps to increase the size of a bony body cavity, in this case the pelvis. The sacrum is normally positioned so that its base is located anterior to its apex. Therefore the sacral curve faces anteriorly and inferiorly (Williams et al., 1995). The sacral curve is more pronounced in humans than in other mammals, including monkeys and apes. In addition, the human sacral curve is almost nonexistent in infants but becomes more pronounced with age (Abitbol, 1989). The combination of upright posture, supine sleeping posture, and a well-developed levator ani muscle are responsible for the increased sacral curve in humans. Abitbol (1989) also found that the frequency of sleeping in the supine posture, and the younger the age when this posture was first assumed for sleeping, were positively associated with the size of the sacral curve.

The sacrum ossifies much like any other vertebra, with one primary center located in the anterior and centrally located primitive vertebral body and one primary center in each posterior arch. Unique to the sacrum is that the costal elements develop separately and then fuse with the remainder of the posterior arch to form the solid mass of bone lateral to the pelvic sacral foramina. Secondary centers of ossification are complex, with centers developing on the superior and inferior aspects of each sacral vertebral body, the lateral and the anterior aspects of each costal element, the spinous tubercles, and the lateral (auricular) surface of the sacrum. Most centers fuse by approximately the twenty-fifth year of life, but ossification and fusion of individual segments continue until later in life. Early in development, fibrocartilage forms between sacral bodies. These represent rudimentary intervertebral discs (IVDs) and usually become surrounded by bone as the sacral bodies fuse with one another. However, the central region of these “discs” usually remains unossified throughout life.

Sacral Base

The sacral base is composed of the first sacral segment. It has a large body that is the homologue of the vertebral bodies (see Figs. 8-1 and 8-2). This body is wider from left to right than from front to back. The anterior lip of the sacral body is known as the promontory. The vertebral foramen of the first sacral segment is triangular in shape and forms the beginning of the sacral canal. This canal extends the length of the sacrum. The pedicles of the first sacral segment are small and extend to the left and right laminae. The laminae of the first segment meet posteriorly to form the spinous tubercle. The transverse processes (TPs) extend laterally and fuse with the costal elements to form the large left and right sacral alae, which are also known as the lateral sacral masses. The bony trabeculae of the inner cancellous bone of the sacral ala are significantly less dense than those in the sacral bodies (Peretz, Hipp, and Heggeness, 1998). Each lateral sacral mass is concave on its anterior surface, allowing it to accommodate the psoas major muscle. The psoas major passes across the sacrum before inserting onto the lesser trochanter of the femur.

Extending superiorly from the posterior surface of the sacral base are the left and right articular processes. These processes generally face posteriorly and slightly medially. However, the plane in which these processes lie varies considerably (Dommisse and Louw, 1990). Their orientation ranges from nearly a coronal plane to almost a sagittal one. These processes also frequently are asymmetric in orientation, with one process more coronally oriented and the other more sagittally oriented. Such asymmetry is known as tropism and usually can be detected on standard anterior-posterior x-ray films. The superior articular processes possess articular facets on their posterior surfaces that articulate with the inferior articular facets of the L5 vertebra. The zygapophysial (Z) joints formed by these articulations are more planar than those between two adjacent lumbar vertebrae, and they usually are much more coronally oriented than the lumbar Z joints (see Chapter 7). However, because of the wide variation of the plane in which the superior articular processes lie, the orientation of the lumbosacral Z joints also varies in corresponding fashion.

The muscular and ligamentous attachments to the sacral base and the anterior and posterior surfaces of the sacrum are listed in Table 8-1. This table also provides the key anatomic relationships between these regions of the sacrum, and the neural, muscular, and visceral structures that contact them.

Table 8-1 Attachments and Relationships to the Sacrum

| Surface | Attachments or Relationships |

|---|---|

| Base | |

| Anterior | |

| Posterior | |

| Ventral | |

| Dorsal | |

From Williams PL et al. (1995). Gray’s anatomy (38th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

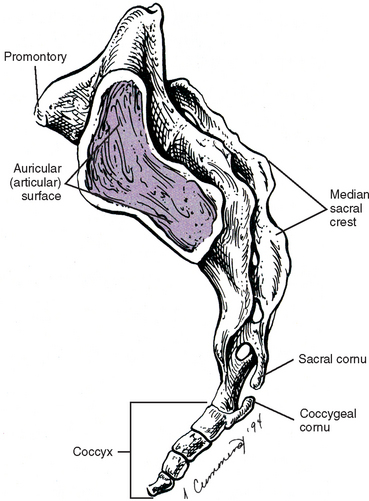

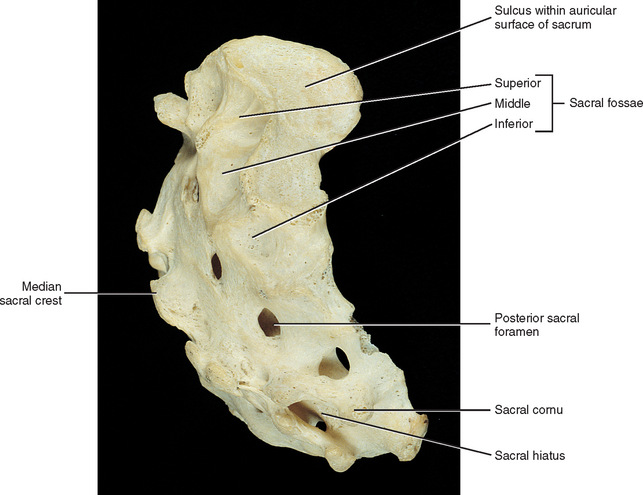

Lateral Surface

The lateral surface of the sacrum (see Fig. 8-2) is composed of the TPs of the five sacral segments, fused with the costal elements of the same segments. This surface contains the auricular surface. The auricular surface of the sacrum articulates with the auricular surface of the ilium. The sacral auricular surface is concave posteriorly and extends across the lateral aspects of three of the five sacral segments. Within the region surrounded by the concavity of the auricular surface are several elevations and depressions that serve as attachment sites for the ligaments that support the sacroiliac joint posteriorly. These ligaments and the sacroiliac joint are discussed in detail later in this chapter. Inferior to the auricular surface, the lateral surface of the sacrum curves medially and becomes thinner from anterior to posterior. The inferior and lateral angle of the sacrum is located at roughly the level of the junction of the fourth and fifth sacral segments. Below this angle the sacrum rapidly tapers to the sacral apex. The apex of the sacrum has an oval-shaped facet on its inferior surface for articulation with a small disc between the sacrum and coccyx.

Sacral Canal and Sacral Foramina

Structures Exiting the Sacral Hiatus.

Both the left and the right S5 nerves and the coccygeal nerve of each side exit the sacral hiatus just medial to the sacral cornua of the same side. They proceed inferiorly and laterally, wrapping around the inferior tip of the sacral cornua (see Dorsal Surface). The posterior primary divisions (PPDs) of these nerves pass posteriorly and inferiorly to supply sensory innervation to the skin over the coccyx. The S5 and coccygeal anterior primary divisions pass anteriorly to pierce the coccygeus muscle and enter the inferior aspect of the pelvis. Here they are joined by the ventral ramus of the S4 nerve to form the coccygeal plexus. This small plexus gives off the anococcygeal nerves that help to supply the skin adjacent to the sacrotuberous ligament.

Ventral Surface

The junctions of the five fused sacral segments form lines that can be seen running across the central aspect of the anterior, or pelvic, surface of the sacrum. These junctions are known as the linea transversaria (also known as transverse lines, or transverse ridges). Remnants of the IVDs are located just deep to the transverse lines. These “discs” frequently remain throughout life and can be seen on standard x-ray films and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The vertebral bodies of the five fused sacral segments lie between the transverse lines and medial to the pelvic sacral foramina (see Fig. 8-1).

The ventral surface of the sacrum displays four pairs of ventral (pelvic or anterior) sacral foramina. These foramina are continuous posteriorly and medially with the sacral IVFs. The sacral IVFs, in turn, are continuous with the more medially located sacral canal. The anterior primary divisions (APDs) of the S1 through S4 sacral nerves exit the pelvic sacral foramina. The APDs are accompanied within these openings by branches of the lateral and median sacral arteries and by segmental veins. Located between the pelvic sacral foramina of the same side are the costal elements. The cortical bone in these regions between the ventral sacral foramina is sturdy (dense), and the cortical bone between the S1 and S2 ventral sacral foramina is the most dense bone of the entire sacrum (Ebraheim et al., 2000). The costal elements fuse posteriorly with the TPs of the sacral segments.

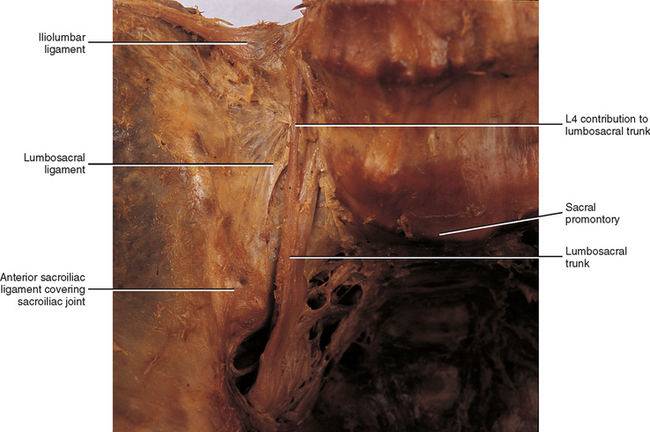

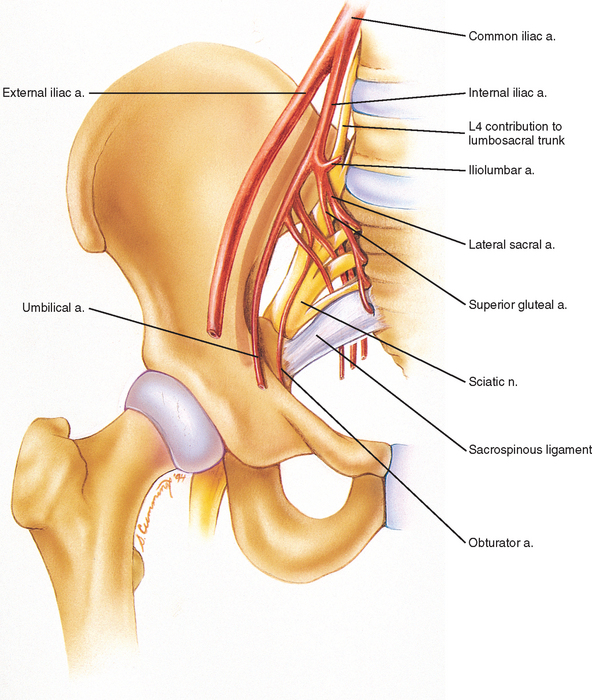

The muscular and ligamentous attachments to the anterior surface of the sacrum are listed in Table 8-1. Also, Figures 8-20 and 8-21 demonstrate the major arteries and nerves associated with the anterior surface of the sacrum.

Dorsal Surface

The dorsal surface of the sacrum is irregular in shape (see Fig. 8-1). The superior articular processes extend from the superior aspect of the sacral base (see Sacral Base).

The posterior surface of the sacrum contains five longitudinal (vertical) ridges known as the median, intermediate (left and right), and lateral (left and right) sacral crests (see Fig. 8-1). These crests are homologous to the spinous processes, articular processes, and the TPs of the rest of the spine, respectively.

The left and right intermediate, or medial, sacral crests are located just medial to the posterior (dorsal) sacral foramina. They are formed by four fused articular tubercles on each side of the sacrum (S2-5 tubercles; the S1 articular process is distinct). The left and right fifth articular tubercles extend inferiorly as the sacral cornua. The sacral cornua come to blunted tips inferiorly. They form the left and right inferior boundaries of the sacral hiatus (Fig. 8-1).

The muscular and ligamentous attachments to the posterior surface of the sacrum are listed in Table 8-1.

Fusion of the L5 vertebra with the sacrum (sacralization) is discussed in Chapter 7 and shown in Figures 12-14, G and H. The first sacral segment also may separate from the sacrum, known as lumbarization. The separation may be complete but usually is unilateral, and a joint may develop between the TP of the lumbarized segment and the remainder of the sacrum. Also, the first coccygeal segment may fuse with the sacrum.

Sacrococcygeal Joint

A fibrocartilaginous disc typically exists between the apex of the sacrum and the coccyx, making this joint a symphysis. However, occasionally a synovial joint develops here. At the other extreme, this region may completely fuse in older individuals (Williams et al., 1995).

Table 8-2 lists all the ligaments of the sacrococcygeal joint by their coccygeal attachments, as well as the muscles attaching to the coccyx.

Table 8-2 Attachments and Relationships to the Coccyx

| Surface | Attachments or Relationships |

|---|---|

| Anterior | Pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus (coccygeus) muscles, ventral sacrococcygeal ligament (similar to anterior longitudinal ligament) |

| Posterior | Gluteus maximus and sphincter ani externus (to tip of apex) muscles, intercornual ligaments, deep and superficial dorsal sacrococcygeal ligament,* filum terminale externum |

| Lateral | Lateral sacrococcygeal ligament (from transverse process of coccyx to inferolateral angle of sacrum) |

* The superficial part runs between the sacral cornua (it closes the inferior aspect of the sacral canal at the sacral hiatus). The deep part is similar in location (and function) to the posterior longitudinal ligament. The filum terminale externum passes between the two parts of this ligament before attaching to the coccyx.

From Williams PL et al. (1995). Gray’s anatomy (38th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Clinical Implications.

Sacral fractures are present in as many as 45% of pelvic fractures (Gibbons, Soloniuk, and Razack, 1990). These fractures may go undetected if caudal, cephalic, and oblique x-ray examinations of the pelvis are not performed. Fractures of the sacrum can damage the APDs of the lumbosacral plexus, and fractures involving the sacral canal may affect the sacral roots before they are able to exit the sacrum.

Gibbons, Soloniuk, and Razack (1990) found neurologic deficits in 34% of patients with sacral fractures. They also noted that the neurologic deficits usually improved with time. The presence and type of nerve injury correlated with the type of sacral fracture. Patients with injuries that involved only the sacral ala had the lowest incidence of neurologic deficit, although L5 or S1 radiculopathy was found in 24% of these patients. The mechanism of L5 radiculopathy was thought to be caused by entrapment of the APD of L5 between the fractured, superiorly displaced ala and the TP of L5.

Gibbons, Soloniuk, and Razack (1990) also found that fractures involving the pelvic sacral foramina usually were vertical fractures that passed through all four foramina of one side. These injuries always were associated with other pelvic fractures and had a 29% incidence (two of seven fractures) of unilateral L5 or S1 nerve root involvement. However, bowel and bladder functions were maintained; a bilateral lesion is necessary to affect these functions.

Fractures involving the sacral canal can be either transverse (horizontal) or vertical and have the greatest chance of causing nerve damage (57% with horizontal and 60% with vertical). Vertical fractures usually are associated with other pelvic fractures and can result in bladder and bowel dysfunction (Gibbons, Soloniuk, and Razack, 1990; Ebraheim, Biyani, and Salpietro, 1996).

Horizontal fractures of the sacrum affecting the sacral canal are not necessarily associated with other pelvic fractures. They can be isolated injuries caused by a direct blow, as might occur from a long fall. The inferior fragment sometimes is considerably displaced, and severe neurologic deficits, involving bladder and bowel functions, can occur if the fracture is above the S4 segment (Gibbons, Soloniuk, and Razack, 1990).

SACROILIAC JOINT

General Considerations

The degree to which low back pain is caused by pathologic conditions or dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) has been discussed for many decades. The SIJ is now gaining added attention as a primary source of low back pain (Cassidy and Mierau, 1992; Daum, 1995; Schwarzer, Aprill, and Bogduk, 1995; Dreyfuss et al., 1996). One reason for this is that protrusion of the IVD is now considered to be a relatively infrequent cause of low back pain, accounting for less than 10% of the pain in this region (Cassidy and Mierau, 1992). On the other hand, pain arising from the SIJ is reported to account for more than 20% of low back pain (Kirkaldy-Willis, 1988) and may be implicated to some extent in more than 50% of patients with low back pain (Cassidy and Mierau, 1992). This makes the SIJ an area of significant clinical importance. An understanding of the unique and interesting anatomy of this joint is essential before a clinician can properly diagnose and treat pain arising from this articulation.

The pelvic ring possesses five distinctly different types of joints: the lumbosacral Z joints, the anterior lumbosacral (L5-S1 IVD), coxal (hip), SIJ, and symphysis pubis. The dynamic interactions between these joints are not well understood. Because the pelvic ring is complex and actually involves a total of eight joints (left and right Z joints, coxals, and SIJs; plus the single lumbosacral joint and the pubic symphysis), any change in the trunk or lower extremity is compensated in some way by the complicated dynamic mechanism of the pelvic ring (Lichtblau, 1962; Winterstein, 1972; LaBan et al., 1978; Sandoz, 1978; Grieve, 1981; Fidler and Plasmans, 1983; Wallheim, Olerud, and Ribbe, 1984; Drerup and Hierholzer, 1987). In fact, a survey of the pelvic rings of asymptomatic schoolchildren 7 to 8 years of age revealed distortion (asymmetry) in 40% of them. Surgical removal of graft material from the pelvic bone (iliac crest) also causes distortion of the pelvic ring (Grieve, 1975; Beal, 1982; Diakow, Cassidy, and DeKorompay, 1983).

The SIJ and symphysis pubis move a small amount. At first inspection, what little motion they have may seem enigmatic at best. Some authors have stated that the sole function of these two joints simply is to widen the pelvic ring during pregnancy and parturition. The joints are aided in this action by the hormone relaxin (Simkins, 1952; Bellamy, Park, and Rodney, 1983). Others believe the SIJs move during many activities. An incomplete list of activities thought to enlist the movement of the SIJ includes the following: locomotion, spinal and thigh movement, and changes of position (from lying to standing, standing to sitting, etc.).

The SIJ is thought to move a minimum of 2 mm and 2 degrees, but this small amount of movement is complex (Pitkin and Pheasant, 1936b; Weisl, 1955; Colachis et al., 1963; Wood, 1985; Sturesson, 1989; Brunner, Kissling, and Jacob, 1991; Barakatt et al., 1996; Smidt et al., 1997). Janse (1978) stated that the function of movement in the SIJ is to convert the pelvis into a resilient, accommodating receptacle essential to the ease of locomotion, weight bearing, and shock absorption. This is in agreement with other authors (DonTigny, 1990; King, 1991) who state that the function of SIJ is to buffer, absorb, direct, and compensate for forces generated from above (gravity, carrying the torso, and muscle action) and below (forces received during standing and locomotion).

Unique Characteristics

Differences between humans and quadrupeds.

The pelvis tilts anteriorly and inferiorly in the bipedal human, and the SIJ is aligned in parallel fashion with the vertebral column, whereas the pelvis of quadrupedal animals is tilted more posteriorly. The SIJ of the bipedal human has other differences associated with a two-legged stance. These include the articulating surfaces of the SIJ that are shaped like an inverted L, the interosseous ligaments that are more substantial and stronger posteriorly, and the many bony interlockings between the sacrum and the ilium that develop with age (Walker, 1986).

Differences among humans.

The plane of articulation of SIJs can vary from one individual to another; and the left and right SIJs of one individual can even lie in different planes (Ebraheim et al., 1997b). The weight of the human trunk is transmitted by gravity through the lumbosacral joint and is then divided onto the right and left SIJs. In addition, the ground reaction, or bouncing force, is transmitted through the hip joints and also acts on the SIJs. Adapting to the bipedal requirements of mobility and stability may account for the tremendous amount of variation and asymmetry found in the human SIJ. The joint structure and the surface contours of the SIJ have changes associated with age, sex, and the mechanical loads that are placed on them (Walker, 1986). Therefore the functional requirements of the SIJ, to a great extent, may influence the structural changes found in them (Weisl, 1954a). For example, one may speculate that more mobility is necessary in the SIJ in younger persons, females around the time of parturition, and athletes. On the other hand, more stability is necessary in older persons, males (generally larger body weight), and those who frequently carry heavy weights. This stability may be provided by the development of stronger interosseous ligaments and a more prominent series of bony interlockings (Table 8-3). Also, the osteophytes and ankylosis frequently seen in the SIJs of older individuals may develop to increase stability.

Table 8-3 “Tongue and Groove” Relationships (Bony Interlockings) between the Sacrum and Ilium*

| Sacral E or D | Iliac E or D |

|---|---|

| Sacral groove (D) | Iliac ridge (E) |

| Middle sacral fossa (see text) (D) | Iliac tuberosity (E) |

| Sacral tuberosity (E) | Sulcus between iliac ridge and iliac tuberosity (iliac sulcus) (D) |

| Additional elevation on posterior and superior surface of sacral ala (alar tuberosity) (E) | Depression anterior and superior to iliac tuberosity (D) |

E, Elevation; D, depression.

Structure

General Relationships.

The SIJ is an articulation between the auricular surface of the lateral aspect of the sacrum and the auricular surface of the medial aspect of the ilium (see Figs. 8-6 and 8-7). Previously this joint was classified as an amphiarthrosis. However, the SIJ is now classified as an atypical synovial joint with a well-defined joint space and two opposing articular surfaces (Cassidy and Mierau, 1992). Each auricular surface is shaped like an inverted L (Williams et al., 1995). Other authors have described it as being C shaped (Cassidy and Mierau, 1992). The superior limb of this surface is oriented posteriorly and superiorly, and the inferior limb is oriented posteriorly and inferiorly (Figs. 8-2 to 8-9). Consequently, the upper, middle, and lower regions of the SIJ have distinctly different appearances when viewed in the horizontal plane, as is done with MRI and computed tomography (CT) scans (Fig. 8-10). An articular capsule lines the SIJ’s anterior aspect, whereas the SIJ’s posterior aspect is covered by the interosseous sacroiliac (S-I) ligament. No articular capsule has been found along the posterior joint surface.