Chapter Fifty-Six. The puerperium

Introduction

Postpartum is a descriptive term attributed to situations and conditions following birth (parturition). The postnatal period is a social concept occurring after birth and usually involving the baby. In the Midwives Rules and Standards (NMC 2004) the postnatal period is defined as being:

a period after the end of labour during which the attendance of a midwife upon a woman and baby is required, being not less than ten days and for such longer period as the midwife considers necessary.

The puerperium occurs during a time when the anticipation of pregnancy and the excitement of the birth are over. This period can be a particularly vulnerable time for women as they not only have to deal with the physiological changes to their bodies but also have to cope with any emotional, psychological and social adaptations brought about by their new role.

This chapter will address the physiology of the puerperium and the influences on emotional reactions and mental disorders associated with childbirth. Other aspects of postnatal care, which include family planning (Ch. 6) and interactive aspects of parenting (Ch. 57), are considered in other relevant sections within the book. The main maternal puerperal complications include postpartum haemorrhage, thromboembolic disorders, puerperal infections and mental health disorders. Postpartum haemorrhage can be found in Chapter 45; thromboembolic disorders, including thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are discussed in Chapter 33. The remaining disorders are considered in this chapter.

Physiological changes

During the puerperium the physiological changes can be divided into:

• Involution of the uterus and genital tract.

• Secretion of breast milk and establishment of lactation.

• Other physiological changes.

The major physiological event of the puerperium is lactation, thus Chapter 54 and Chapter 55 are devoted to this important topic. These chapters include the anatomy of the breast and the initiation and maintenance of lactation and breastfeeding.

Endocrine changes in the puerperium

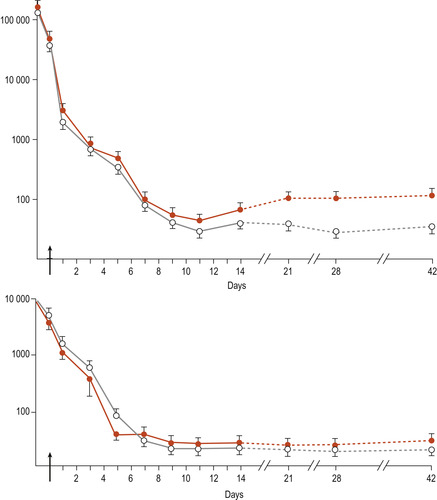

Immediately following delivery of the placenta, there is a profound decrease in the serum levels of placental hormones: i.e. human placental lactogen (hPL), human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), oestrogen and progesterone. The removal of the placental hormones initiates reversal of most of the pregnancy-related changes. The rate of removal of the hormones depends on their half-life. Hormones are first removed from maternal blood. Secondary removal occurs as the hormones are mobilised from the tissues. Within 24 h, plasma estradiol decreases to levels that are less than 2% of pregnancy levels. Oestrogen levels return almost to pre-pregnant levels by 7 days. Progesterone levels return to those found in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle by 24–48 h and to the follicular phase by 7 days (Fig. 56.1). The enlarged thyroid gland regresses and the basal metabolic rate returns to normal.

|

| Figure 56.1 Mean (±SEM) serum concentrations of 17β-oestradiol and progesterone in lactating and non-lactating subjects. Lactating subjects ( n = 10) ○–○; non-lactating subjects ( n = 9) •–•. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Resumption of menstruation and ovulation

Most women are relatively infertile during the postnatal period and this may continue during the period of lactation. The return of ovulation is preceded by an increase in plasma progesterone. There is a wide variation in the return to ovulation, irrespective of whether the woman is breastfeeding or not. In most cases, the first menstrual cycle following delivery is anovulatory. However, ovulation may occur before menstruation in 25% of women and pregnancy may result. Anovulatory cycles are more common in lactating women (Blackburn 2007).

Two maternal hormones involved in the initiation and maintenance of lactation will be briefly mentioned here; they are discussed more fully in Chapter 55. Prolactin is secreted by the anterior pituitary gland in increasing amounts during pregnancy but its effects are suppressed by progesterone. Oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary gland. This hormone stimulates electrical and contractile activity in the myometrium to aid involution and is critical for milk ejection during lactation (Blackburn 2007).

Involution

The principal change in the pelvic organs is uterine involution and the uterine fundus will have disappeared below the symphysis pubis within 10 days of delivery (Edmonds 2007). Involution is defined as being:

a normal process characterised by a decrease in the size of an organ caused by a decrease in the size of its cells, such as is found in the involution of the uterus in the postpartum period.

During this process, the uterus returns to its normal size, tone and position and the vagina, uterine ligaments and muscles of the pelvic floor also return to their pre-pregnant state. The pelvic floor and subsequent problems that can arise if the ligaments and muscles are permanently weakened are discussed in Chapter 25.

Physiology

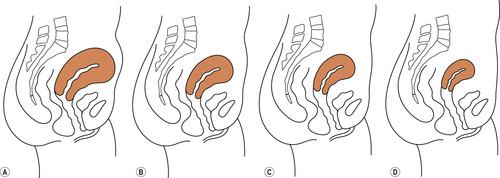

During involution there are changes to the myometrium or muscle layer and the decidua or lining of the pregnant uterus (Fig. 56.2). The muscle layer returns to normal thickness by the processes of ischaemia, autolysis and phagocytosis. The decidua is shed as lochia and there is regeneration of the endometrium.

• Ischaemia occurs when the muscles of the uterus retract at the end of the third stage to constrict the blood vessels at the placental site, resulting in haemostasis. Blood circulating to the uterus is greatly reduced.

• Autolysis is the process of removal of the redundant actin and myosin muscle fibres and cytoplasm by proteolytic enzymes and macrophages. Individual myometrial cells are reduced in size with no significant reduction in the numbers of cells.

• Phagocytosis removes the excess fibrous and elastic tissue. This process is incomplete and some elastic tissue remains so that a uterus that has held a pregnancy never quite returns to the nulliparous state.

|

| Figure 56.2 Involution of the uterus. (A) At the end of labour. (B) One week after delivery. (C) Two weeks after delivery. (D) Six weeks after delivery. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Positional changes

The most marked reduction in the size of the uterus takes place during the first 10 days. The process of involution is not complete until about 6 weeks and the rate at which the uterus involutes varies between women (Edmonds 2007).

Immediately after delivery of the placenta the whole uterus contracts down fully and the uterine walls become realigned in apposition to each other (Coad & Dunstall 2005). The uterus weighs about 1000 g at this time. The fundus is palpable just below or at the level of the umbilicus which is about 11–12 cm above the symphysis pubis (Edmonds 2007). The muscles are well contracted to aid the process of haemostasis and at this time the uterus feels globular and hard like a cricket ball. Between 1 and 12 h after delivery, the myometrium relaxes slightly, whilst continuing to remain firmly contracted (Coad & Dunstall 2005, Edmonds 2007). Further active bleeding is prevented by the activation of the blood-clotting mechanisms which are altered greatly during pregnancy to facilitate a swift clotting response (Coad & Dunstall 2005).

On average the height of the fundus then decreases at a rate of 1 cm daily. At the end of the 1st week, the uterus has lost 50% of its bulk, weighs about 500 g and is about 5 cm above the symphysis pubis. It has returned to the true pelvis by the 10th postnatal day. By the end of the 6th week after delivery, the uterus should weigh between 60 and 80 g and has returned to its pre-pregnant position of anteversion and anteflexion.

This normal process of involution is slower when there has been overdistension of the uterus due to multiple pregnancy or a large baby or if the pregnancy has been complicated by polyhydramnios. Slow involution may be associated with retained placental tissue or blood clot, particularly if there is an associated infection. There is no evidence to suggest that there is any relationship between parity and the rate of involution.

Uterine contractions

During the first 24 h after delivery, oxytocin leads to uterine contractions with further retraction. The contractions can be quite strong and often result in after-pains, especially in multiparous women. Suckling stimulates oxytocin release. This gradually diminishes over the next 4–7 days and the pain is relieved by mild analgesia.

The decidua

The upper portion of the spongy endometrial layer is sloughed off when the placenta is delivered. The remaining decidua is organised into basal and superficial layers. The superficial layer consists of granulation tissue, which is invaded by leucocytes to form a barrier to prevent micro-organisms invading the remaining decidua. This layer becomes necrotic and is sloughed off as the lochia. The basal layer remains intact and is the source of regeneration of the endometrium, which begins about 10 days after delivery. The regeneration process is completed by 2–3 weeks following delivery, with the exception of the placental site.

Healing of the placental site is complete by the end of 6 weeks. Immediately after delivery, the placental site is reduced to a raised roughened area about 12 cm in diameter. It contains many thrombosed sinusoids. The large blood vessels that supplied the intervillous space are invaded by fibroblasts and their lumen is obscured. Some of the blood vessels later recanalise.

Lochia

The vaginal loss during the puerperium is known as the lochia (a plural word). Lochia vary in amount, content and colour as the excess tissue is lost. Women lose between 150 and 400 ml of lochia, averaging 225 ml.Women who breastfeed have less lochia, possibly due to more rapid involution and healing, although flow may increase temporarily during suckling. Three forms of lochia are described: rubra (red), serosa (pink) and alba (white).

Lochia consist of blood, leucocytes, shreds of deciduas and organisms. A summary of the characteristics of lochia is presented in Table 56.1. The lochia may remain red for up to 3 weeks or there may be a brief increase in blood content in the 2nd week. However, lochia remaining heavily bloodstained or a sudden return to profuse red lochia may suggest that placental tissue has been retained. If the lochia are offensive and the woman becomes pyrexial, uterine infection may be present, and she must be assessed by a doctor and appropriate treatment commenced.

| Type | Content | Average days |

|---|---|---|

| Lochia rubra | Blood, amnion and chorion, decidual cells, vernix, lanugo, meconium | 1–3 |

| Lochia serosa | Blood, wound exudate, erythrocytes, leucocytes, cervical mucus, micro-organisms, shreds of degenerating decidua from the superficial layer | 4–10 |

| Lochia alba | Leucocytes, decidual cells, mucus, bacteria, epithelial cells | 11–21 |

Findings from research studies indicate that vaginal loss during the puerperium is considerably more varied in duration, amount and colour than classically reported and described in textbooks (Marchant et al., 1999 and Marchant et al., 2003, Sherman et al 1999).

Other parts of the genital tract

Immediately after delivery, the cervix is soft and highly vascular but it rapidly loses its vascularity and returns to its original form and normal consistency within a few days of delivery (Edmonds 2007). The external os remains sufficiently dilated to admit one finger for weeks or months (and in some cases permanently) but the internal os becomes closed during the 2nd week of the puerperium (Howie 1995). The ovaries and fallopian tubes return with the uterus to the pelvic cavity. The vagina almost always shows some evidence of parity. The vagina, vulva and pelvic floor respond to the reduced amount of circulating progesterone by recovering normal muscle tone. Early ambulation and postnatal exercises can enhance this return to normal. Bruising or tears to genital tissues heal rapidly and any oedema is reabsorbed within the first 3 or 4 days.

The body systems

The cardiovascular and respiratory systems

During pregnancy, the increased circulatory volume and haemodilution are needed to ensure adequate blood supply to the uterus and placental bed. Following the withdrawal of oestrogen, a diuresis occurs for the first 48 h and the plasma volume and haematocrit rapidly return to normal. The reduction in circulating progesterone leads to removal of excess tissue fluid and a return to normal vascular tone. There is an increase in atrial natriuretic peptide, which may contribute to the well-recognised diuresis that occurs during this period (de Swiet 1998). Cardiac output and blood pressure return to non-pregnant levels.

Delivery of the baby and reduction in uterine size remove the compression of the lungs. Full inflation of the lungs, including the basal lobes, is again possible. With the reduction in cardiac work and circulatory volume and the decrease in metabolism, oxygen demands now return to normal. The tendency to hyperventilation disappears, and blood carbon dioxide levels return to normal, as does the slight alkalosis.

The renal system

There is reversal of the physiological parameters of the renal system to pre-pregnancy levels by the end of the puerperium. During this time, the kidneys must cope with the excretion of excess fluids and an increase in the breakdown products of protein. The dilatation of the renal tract resolves with the removal of progesterone and the renal organs gradually return to their pre-pregnant state. During labour, the bladder is displaced into the abdomen and the urethra is stretched. There may be loss of tone in the bladder and bruising of the urethra, leading to difficulty in micturition.

Because of these features and diuresis, the bladder may become overdistended and retention of urine may occur. This may be missed if the carer fails to notice that frequent small amounts of urine are being passed with the bladder becoming ever more distended. Early ambulation with frequent encouragement to pass urine and ensuring that the bladder is emptied will help to avoid this situation. Catheterisation may occasionally be necessary.

The gastrointestinal tract

Throughout the body, smooth muscle tone gradually returns to normal due to the reduced levels of circulating progesterone. There is a rapid return to normal carbohydrate metabolism and fasting plasma insulin levels return to non-pregnant values between 48 h and the 6th week postpartum (Campbell-Brown & Hytten 1998). The minor inconveniences of pregnancy affecting the gastrointestinal tract, such as constipation and heartburn, resolve. Constipation may persist as a problem, possibly due to inactivity or a fear of pain on defecation.

Puerperal infection

At delivery, the normal protective barriers against infection are temporarily broken down, and this gives potential pathogens an opportunity to pass from the lower genital tract into the usually sterile environment of the uterus. Prior to the introduction of aseptic techniques and development of antibiotics, puerperal sepsis was an important cause of maternal mortality. Puerperal pyrexia was then a notifiable disease. Puerperal pyrexia may have several explanations but it is a clinical sign that always merits careful investigation (Lewis 2007

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree