Fig. 1.1 Justinus Kerner; photograph of 1855.

Kerner again disputed that an inorganic agent such as hydrocyanic acid could be the toxic agent in the sausages, suspecting a biological poison instead. After he had observed further cases, Kerner published a first monograph in 1820 on “sausage poisoning” in which he summarized the case histories of 76 patients and gave a complete clinical description of what we now recognize as botulism. The monograph was entitled “Neue Beobachtungen über die in Württemberg so häufig vorfallenden tödlichen Vergiftungen durch den Genuss geräucherter Würste [New Observations on the Lethal Poisoning that occurs so frequently in Württemberg Owing to the Consumption of Smoked Sausages] (Kerner, 1820). Kerner compared the various recipes and ingredients of all sausages that had produced intoxication and found that among the ingredients of blood, liver, meat, brain, fat, salt, pepper, coriander, pimento, ginger and bread the only common ones were fat and salt. Because salt was probably known to be “innocent,” Kerner concluded that the toxic change in the sausage must take place in the fat and, therefore, called the suspected substance “sausage poison,” “fat poison” or “fatty acid.” Later Kerner speculated about the similarity of the “fat poison” to other known poisons, such as atropine, scopolamine, nicotine and snake venom, which led him to the conclusion that the fat poison was probably a biological poison (Erbguth, 2004).

In 1822, Kerner published 155 case reports including autopsy studies of patients with botulism and developed hypotheses on the “sausage poison” in a second monograph Das Fettgift oder die Fettsäure und ihre Wirkungen auf den thierischen Organismus, ein Beytrag zur Untersuchung des in verdorbenen Würsten giftig wirkenden Stoffes [The Fat Poison or the Fatty Acid and its Effects on the Animal Body System, a Contribution to the Examination of the Substance Responsible for the Toxicity of Bad Sausages] (Kerner, 1822) (Fig. 1.2). The monograph contained an accurate description of all muscle symptoms and clinical details of the entire range of autonomic disturbances occurring in botulism, such as mydriasis, decrease of lacrimation and secretion from the salivary glands, and gastrointestinal and bladder paralysis. Kerner also experimented on various animals (birds, cats, rabbits, frogs, flies, locusts, snails) by feeding them with extracts from bad sausages and finally carried out high-risk experiments on himself. After he had tasted some drops of a sausage extract he reported: “. . .some drops of the acid brought onto the tongue cause great drying out of the palate and the pharynx” (Erbguth and Naumann, 1999).

Fig. 1.2 Title of Justinus Kerner’s second monograph on sausage poisoning, 1822.

Kerner deduced from the clinical symptoms and his experimental observations that the toxin acts by interrupting the motor and autonomic nervous signal transmission (Erbguth, 1996). He concluded: “The nerve conduction is brought by the toxin into a condition in which its influence on the chemical process of life is interrupted. The capacity of nerve conduction is interrupted by the toxin in the same way as in an electrical conductor by rust” (Kerner, 1820). Finally, Kerner tried in vain to produce an artificial “sausage poison.”

In summary, Kerner’s hypotheses concerning “sausage poison” were that (1) the toxin developed in bad sausages under anaerobic conditions, (2) the toxin acts on the motor nerves and the autonomic nervous system, and (3) the toxin is strong and lethal even in small doses (Erbguth and Naumann, 1999).

In Chapter 8 of the 1822 monograph, Kerner speculated about using the “toxic fatty acid” botulinum toxin for therapeutic purposes. He concluded that small doses would be beneficial in conditions with pathological hyperexcitability of the nervous system (Erbguth, 2004). Kerner wrote: “The fatty acid or zoonic acid administered in such doses, that its action could be restricted to the sphere of the sympathetic nervous system only, could be of benefit in the many diseases which originate from hyperexcitation of this system” and “by analogy it can be expected that in outbreaks of sweat, perhaps also in mucous hypersecretion, the fatty acid will be of therapeutic value.” The term “sympathetic nervous system” as used during the Romantic period, encompassed nervous functions in general. “Sympathetic overactivity” then was thought to be the cause of many internal, neurological and psychiatric diseases. Kerner favored the “Veitstanz” (St. Vitus dance – probably identical with chorea minor) with its “overexcited nervous ganglia” to be a promising indication for the therapeutic use of the toxic fatty acid. Likewise, he considered other diseases with assumed nervous overactivity to be potential candidates for the toxin treatment: hypersecretion of body fluids, sweat or mucus; ulcers from malignant diseases; skin alterations after burning; delusions; rabies; plague; consumption from lung tuberculosis; and yellow-fever. However, Kerner conceded self-critically that all the possible indications mentioned were only hypothetical and wrote: “What is said here about the fatty acid as a therapeutic drug belongs to the realm of hypothesis and may be confirmed or disproved by observations in the future” (Erbguth, 1998).

Justinus Kerner also advanced the idea of a gastric tube, suggested by the Scottish physician Alexander Monro in 1811, and adapted it for the nutrition of patients with botulism; he wrote: “if dysphagia occurs, softly prepared food and fluids should be brought into the stomach by a flexible tube made from resin.” He considered all characteristics of modern nasogastric tube application: the use of a guide wire with a cork at the tip and the lubrication of the tube with oil.

Botulism research after Kerner

After his publications on food-borne botulism, Kerner was well known to the German public and amongst his contemporaries as an expert on sausage poisoning, as well as for his melancholy poetry. Many of his poems were set to music by the great German Romantic composer Robert Schumann (1810–56), who had to quit his piano career because of the development of a pianist’s focal finger dystonia. Kerner’s poem The Wanderer in the Sawmill was the favourite poem of the twentieth century poet Franz Kafka (in full in Appendix 1.1). The nickname “Sausage Kerner” was commonly used and “sausage poisoning” was known as “Kerner’s disease.” Further publications in the nineteenth century by various authors (e.g. Müller, 1869) increased the number of reported cases of “sausage poisoning,” describing the fact that the food poisoning occurred after the consumption not only of meat but also of fish. However, these reports added nothing substantial to Kerner’s early observations. The term “botulism” (from the Latin botulus, sausage) appeared at first in Müller’s reports and was subsequently used. Therefore, “botulism” refers to poisoning caused by sausages and not to the sausage-like shape of the causative bacillus discovered later (Torrens, 1998).

The discovery of “Bacillus botulinus” in Belgium

The next and most important scientific step was the identification of Clostridium botulinum in 1895–6 by the Belgian microbiologist Emile Pierre Marie van Ermengem of the University of Ghent (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3 Emile Pierre Marie van Ermengem 1851–1922.

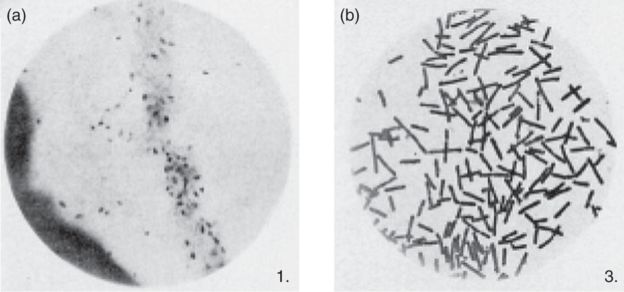

On December 14, 1895, an extraordinary outbreak of botulism occurred amongst the 4000 inhabitants of the small Belgian village of Ellezelles. The musicians of the local brass band “Fanfare Les Amis Réunis” played at the funeral of the 87-year-old Antoine Creteur and as it was the custom gathered to eat in the inn “Le Rustic” (Devriese, 1999). Thirty-four people were together and ate pickled and smoked ham. After the meal, the musicians noticed symptoms such as mydriasis, diplopia, dysphagia and dysarthria, followed by increasing muscle paralysis. Three of them died and ten nearly died. A detailed examination of the ham and an autopsy were ordered and conducted by van Ermengem, who had been appointed Professor of Microbiology at the University of Ghent in 1888 after he had worked in the laboratory of Robert Koch in Berlin in 1883. Van Ermengem isolated the bacterium in the ham and in the corpses of the victims (Fig. 1.4), grew it, used it for animal experiments, characterized its culture requirements, described its toxin, called it “Bacillus botulinus,” and published his observations in the German microbiological journal Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten [Journal of Hygiene and Infectious Diseases] in 1897 (an English translation was published in 1979) (van Ermengem, 1897). The pathogen was later renamed Clostridium botulinum. Van Ermengem was the first to correlate “sausage poisoning” with the newly discovered anaerobic microorganism and concluded that “it is highly probable that the poison in the ham was produced by an anaerobic growth of specific micro-organisms during the salting process.” Van Ermengem’s milestone investigation yielded all the major clinical facts about botulism and botulinum neurotoxin: (1) botulism is an intoxication, not an infection; (2) the toxin is produced in food by a bacterium; (3) the toxin is not produced if the salt concentration in the food is high; (4) after ingestion, the toxin is not inactivated by the normal digestive process; (5) the toxin is susceptible to inactivation by heat; and (6) not all species of animals are equally susceptible.

Fig. 1.4 Microscopy of the histological section of the suspect ham at the Ellezelles botulism outbreak. (a) Numerous spores among the muscle fibers (Ziehl ×1000). (b) Culture (gelatine and glucose) of mature rod-shaped forms of “Bacillus botulinus” from the ham on the eighth day (×1000). (From van Ermengem, 1897.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree