Chapter 7 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. • Describe some characteristics of diversity in a patient population. • List the key elements of a patient-centered approach. Patients are the reason for the existence of the health care team. They look to the perioperative team to fulfill their diverse needs during the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care (Fig. 7-1). The patient is always the center of attention, not just when under the OR spotlight. A patient may be defined as an individual recipient of health care services. • They are worthwhile and unique individuals. • They respond psychosocially on the basis of their personal values, beliefs, and ethnocultural background. • They have the capacity to adapt to their internal and external environments. • They have basic needs that must be met to maintain homeostasis. Needs are factors that must be controlled or redirected to restore altered function. Nursing diagnoses are based on knowledge and understanding of a patient’s needs and how to fulfill them. The surgical patient faces a threat to the needs identified by humanistic psychologist and motivational theorist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970): physical, security, psychosocial, emotional, and spiritual.8 In following Maslow’s concept of a motivational hierarchy of needs to set priorities for care (Fig. 7-2), the basic lower level (physiologic needs) essential for survival must be met first. Satisfaction of the higher level needs for safety and security, belonging and acceptance, self-esteem, and self-actualization can then be met. Health care personnel should be concerned with a total picture of the patient’s needs and consider all of them. Additional information about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be found at http://psychology.about.com/od/theoriesofpersonality /a/hierarchyneeds.htm. To meet a patient’s needs, the health care team should be sensitive to the patient’s feelings about the illness. A patient’s reactions influence his or her behaviors and the staff’s behavioral responses. An understanding of the patient’s basic methods of coping is helpful to the caregiver in developing the plan of care (Table 7-1). TABLE 7-1 • The perception of interaction within the environment creates individual differences in personality, behavior, and needs. • A person’s physical and psychosocial behavior is a response to stimuli in an attempt to maintain homeostasis. • Behavior is complex. Behavioral acts have multiple causes in addition to a major precipitating one. • A person functions on many levels simultaneously. Many factors determine an individual’s response in a given situation. Behavior should be evaluated in light of the person’s specific situation and pertinent social forces such as family, culture, and environment. Patients respond to crises or personal threats in different ways. Some persons face suffering and surgical intervention with extreme courage, dignity, and fortitude. Others may revert to extreme fear or helplessness, even when faced with a relatively safe procedure.8 1. The patient takes in stimuli and processes the information to produce a response. a. Effective adaptation is exhibited by a favorable response. b. Ineffective adaptation is exhibited by an unfavorable response. 2. The environment around and inside the patient is constantly changing. The patient responds either favorably or unfavorably to each change. 3. The health status of the patient integrates the whole person as he or she adapts to changes in internal and external forces. 4. The process of nursing is a science, and the application of patient care is an art. Adaptation may be rapid or slow, depending on the nature of the stimuli and on the patient’s culture, learned responses, and developmental needs. Adaptations may be sensory, motor, or sensorimotor. The extent of adjustment needed is contingent on the type of illness, the magnitude of disability, and the patient’s personality. More information about Roy’s adaptation theory can be found online at http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/Roy_adaptation_model.html. • Hereditary or genetic factors, such as competency of the hormonal or enzymatic system. • Nature of the illness or disease process. This may be influenced by nutritional or immunologic status. • Severity of the illness or the presence of a stigma. • Previous personal experiences with illness. Chronic illness has a disruptive effect on lifestyle. • Age. Children feel threatened, whereas adolescents resent an interruption of activities and are painfully aware of body changes. Older people think about infirmity and death. • Intellectual capacity. Misconceptions can lead to a knowledge deficit about the disease. Impaired cognitive function creates an inability to understand or comprehend. • Disturbed sensorium. Hearing or sight loss intensifies a stressful experience. Extrinsic factors originate from external sources and include the following: • Environment. The physical and social environment of the hospital is not the same as that of the home. • Family role and status. Expectations and authoritative relationships affect lifestyle, attitudes, and communications. • Economic or financial situation. • Religion. Beliefs influence attitudes and values toward life, illness, and death. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses do not permit transfusion of whole blood or blood components. Orthodox Jews must follow dietary laws in any environment. The fatalistic attitudes derived from some religious beliefs give a person little control over his or her environment and can render a patient passive and apathetic. • Cultural background, education, and social class. These factors are closely related to a patient’s emotional responses and living habits. Significant cultural elements such as food habits, daily living patterns, hygiene, family organization, child care, and orientation to the past, present, and future should be analyzed in relation to culture. An ethnic community is really a larger family. Roles taught by a cultural group influence the mores, beliefs, and social interactions of its members. Also, responses to pain may vary according to cultural or ethnic background. Some groups commonly show an exaggerated emotional response, whereas other groups believe concealing suffering and feelings is more appropriate. • Social relationships. Family, significant others, and friends help satisfy the need for reassurance and provide a sense of being cared about. Discussions with anyone other than the patient concerning condition or personal information require the patient’s permission as part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements concerning patient privacy. Details can be found at www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/. 1. Make sure the room is quiet and well lit, with minimal distractions. Deaf patients may perceive extraneous sounds as buzzing or air-rushing. Deafness can be manifest in many degrees. Care is taken not to approach so quietly that the patient becomes startled. 2. Look directly at the patient. Speak clearly and slowly in a moderate tone of voice, with visible but not exaggerated lip movements. Facial expressions, touch, and body gestures can help communicate feelings and instructions. 3. Greet the patient without wearing a facemask and attract the patient’s attention before speaking. Make eye contact. 4. Be sure the patient understands and responds appropriately to questions. 5. To help explain your actions, show the patient any equipment (e.g., a safety strap) before placing it on him or her. 6. Allow the patient to wear a hearing aid in the perioperative environment, if possible. Try to know what type of device the patient uses and how to adjust the controls if it should start humming during the procedure. 1. Address the patient by name in moderate tones and introduce yourself. Make some noise as you approach so as not to startle the patient. 2. Always speak to the patient before touching him or her. A gentle word followed by a gentle touch can be comforting. 3. For prevention of a distressful reaction to unexpected noises or sensations, the patient should be told what is going to happen before any physical contact. 4. Guiding the patient’s hand helps him or her feel secure, such as when being moved onto the operating bed. Patients with an autistic spectral disorder have a variety of cognitive levels. Understanding the individual characteristics of the patient’s condition is useful during communications with the patient.7,9 More information concerning autistic spectral disorder can be found at www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/asd.cfm. Cooperation during the surgical procedure may be hard to attain, and preoperative sedation may be necessary. Decreased intake and increased metabolic demands create nutritional problems in surgical patients. Drug therapy and procedure activities affect nutritional status; this should be considered when planning for a patient’s nutritional needs.4 Table 7-2 describes the effects that certain drugs have on nutrition. The preoperative assessment may reveal risk factors associated with alterations of nutrition. Patients undergoing procedures of the mouth, face, head, and neck may have mechanical difficulty taking adequate nutrition. TABLE 7-2 Drugs That Interfere with Nutritional Status Malnutrition in the surgical patient is caused by an inadequate intake or use of calories and protein preoperatively and/or postoperatively. The discrepancy between the intake of essential nutrients and the body’s demand for them creates a state of impaired functional ability and structural integrity.4 1. Poor tolerance of anesthetic agents 2. Altered wound healing potential a. Decreased protein synthesis postoperatively b. Increased protein wasting and breakdown of skeletal muscle after severe traumatic injury c. Negative nitrogen balance, with a serum albumin value less than 3 g/dL and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) value less than 10 g/dL 3. Decreased serum electrolyte levels associated with anorexia, bulimia, alcoholism, and other chronic metabolic disturbances 4. Increased susceptibility to infection from immunologic incompetence, with a total lymphocyte count less than 1500/mm3 5. Sequential multisystem organ failure Hypermetabolic states can double that requirement to 3000 calories daily. If caloric intake is less than body requirements, protein is converted into carbohydrates for energy. Protein synthesis then becomes insufficient for restoration of body tissues. Box 7-1 describes conditions that place a patient at risk for protein deficiency and malnutrition. Dietary management is used to correct metabolic and nutritional abnormalities before the surgical procedure. In some patients, special nutritional supplements are indicated to build up or compensate for a permanent metabolic handicap. Enteral feedings help maintain the integrity of the gastrointestinal mucosa.4 Successful therapy is indicated by weight gain, a rise in plasma albumin, and a positive nitrogen balance. A chemically defined elemental diet may be administered via the following routes: Diabetes mellitus is an endocrine disorder that affects glucose metabolism and the production of insulin in the beta cells of the pancreas. Insulin is a hormone that helps break down carbohydrates. If insulin is not produced in sufficient quantities or is of poor quality, carbohydrates are not metabolized and are excreted in the urine as glucose. Glucose molecules are large and damage the cellular structure of the renal tubules of the kidneys.1,2 1. Type 1: Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). The pancreas produces little or no insulin, thus necessitating regular administration of insulin via injection. Onset may be at any age but usually occurs in juveniles (adolescents ages 12 to 16 years) and adults up to age 40 years. 2. Type 2: Non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). The pancreas produces varying amounts of insulin. Onset may be at any age but usually occurs after age 40 years in obese persons. Blood glucose levels are controlled by diet and the administration of oral antihyperglycemics. 3. Diabetes mellitus associated with other conditions or syndromes. Impaired glucose tolerance may be the result of pancreatic or hormonal disease, drug or chemical toxicity, abnormal insulin receptors, or other genetic syndromes. The diabetes may be latent, asymptomatic, or borderline. 1. Hyperglycemia and ketonuria a. A rise in blood glucose and ketones can precipitate severe fluid loss, causing dehydration and hyperkalemia from the release of potassium from cells. b. Some medications (e.g., cortisone) increase the level of blood sugar and antagonize the effect of insulin. 2. Ketoacidosis and acetonuria a. These conditions are caused by insulin insufficiency from natural causes or from a reduced or omitted insulin dosage. b. These conditions may result in coma and ultimately death if allowed to progress untreated. 3. Hypoglycemia and hypoglycemic shock a. These conditions are caused by too much insulin. b. They are of faster onset than ketoacidosis. c. Hypoglycemia is especially dangerous. It can occur during major surgical procedures because of the omission or delay of oral intake. d. These conditions can cause brain damage and put stress on the cardiovascular system. Prevention of these states depends on the following: • Physician’s treatment of choice for diabetes • Severity and type of disorder • Existence of complicating conditions • Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance • Inadequate circulation from neurovascular disease, which causes deficient tissue perfusion (Fig. 7-3) • Hyperlipidemia that affects both coronary and peripheral arteries; peripheral edema can lead to gangrene • Delayed wound healing as a result of increased protein breakdown or compromised circulation; glycogenesis, the breakdown of glycogen to glucose in the liver, diverts protein from tissue regeneration • Neuropathy or nervous system disorders, which cause motor and sensory deficit • Nephropathy, which affects small blood vessels in the kidneys • Retinopathy, which affects small vessels in eyes, and blindness • Neuropathic musculoskeletal disease; severe bone destruction may cause neuropathic fractures • Neurogenic bladder, which causes incontinence; urinary tract infections are common Diabetes causes many bodily changes that increase in frequency with duration of the disease. Physiologic dysfunctions, as listed in Table 7-3, make a person with diabetes a potentially high-risk patient. TABLE 7-3 Physiologic Dysfunctions in Patients at High Risk with Diabetes and Obesity

The patient: the reason for your existence

The patient as an individual

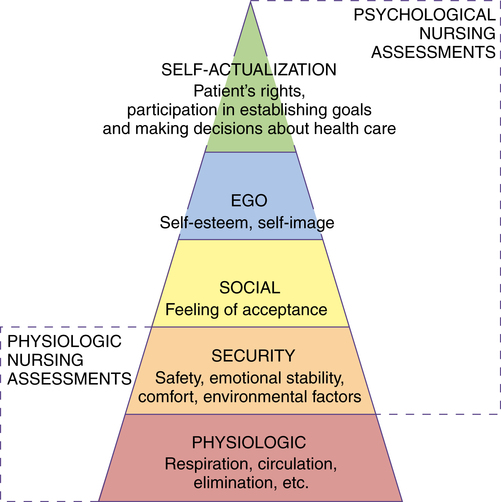

Patients’ basic needs

Hierarchy of needs

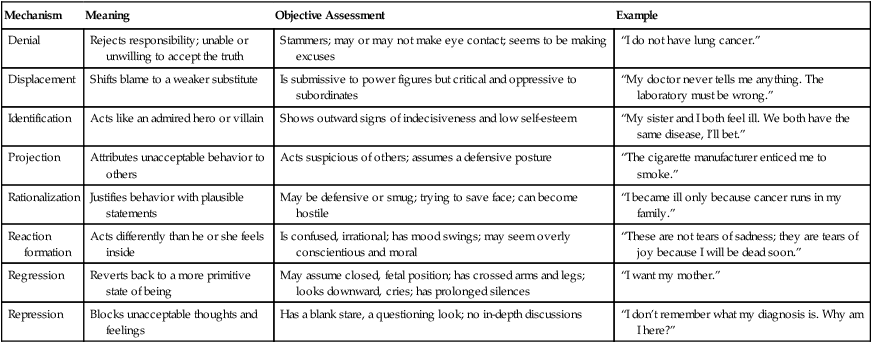

Patients’ reactions to illness

Mechanism

Meaning

Objective Assessment

Example

Denial

Rejects responsibility; unable or unwilling to accept the truth

Stammers; may or may not make eye contact; seems to be making excuses

“I do not have lung cancer.”

Displacement

Shifts blame to a weaker substitute

Is submissive to power figures but critical and oppressive to subordinates

“My doctor never tells me anything. The laboratory must be wrong.”

Identification

Acts like an admired hero or villain

Shows outward signs of indecisiveness and low self-esteem

“My sister and I both feel ill. We both have the same disease, I’ll bet.”

Projection

Attributes unacceptable behavior to others

Acts suspicious of others; assumes a defensive posture

“The cigarette manufacturer enticed me to smoke.”

Rationalization

Justifies behavior with plausible statements

May be defensive or smug; trying to save face; can become hostile

“I became ill only because cancer runs in my family.”

Reaction formation

Acts differently than he or she feels inside

Is confused, irrational; has mood swings; may seem overly conscientious and moral

“These are not tears of sadness; they are tears of joy because I will be dead soon.”

Regression

Reverts back to a more primitive state of being

May assume closed, fetal position; has crossed arms and legs; looks downward, cries; has prolonged silences

“I want my mother.”

Repression

Blocks unacceptable thoughts and feelings

Has a blank stare, a questioning look; no in-depth discussions

“I don’t remember what my diagnosis is. Why am I here?”

Behavior

Adaptation

Stress

Family/significant others

The patient with individualized needs

The patient with sensory impairment or physical challenge

Hearing impairment/deafness

Visual impairment/blindness

Impairment of cognitive function

The patient with alteration of nutrition

Drug

Effect on Nutrition

Aluminum hydroxide

Binds with other nutrients, causing phosphate malabsorption

Aminoglycosides

Reduce carbohydrate metabolism

Amphetamines

Suppress appetite, causing weight loss

Antacids

Alter gastrointestinal pH

Anticholinergics

Decrease gastrointestinal motility, causing malabsorption

Antihistamines

Stimulate appetite and can cause weight gain

Antihypertensives

Decrease gastrointestinal motility, causing malabsorption

Antineoplastics

Impair nutrient absorption

Antirheumatoids

Impair nutrient absorption

Benzodiazepines

Stimulate appetite, causing weight gain

Cathartics

Cause calcium and phosphate loss

Chloramphenicol

Inhibits protein binding

Cytotoxic agents

Suppress appetite, causing weight loss

Immunosuppressives

Suppress appetite, causing weight loss

Isoniazid

Causes pyridoxine deficiency

Neomycin

Interferes with bile acids, causing iron, sugar, and triglyceride malabsorption

Phenobarbital

Causes vitamin D deficiency

Phenothiazides

Stimulate appetite, causing weight gain

Phenytoin

Causes osteomalacia

Steroids

Deplete sodium

Tricyclic antidepressants

Stimulate appetite, causing weight gain

Malnutrition

Nutritional supplements

The patient with diabetes mellitus

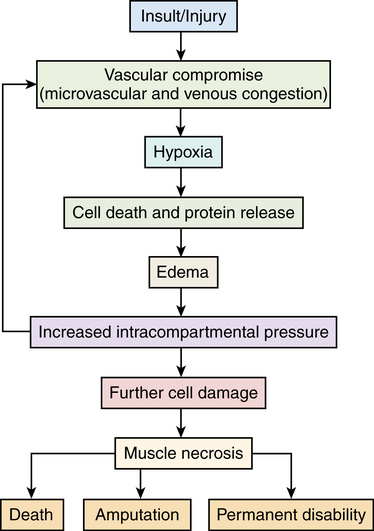

Common complications

Diabetes Mellitus

Obesity

INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

Skin that may be dry, itchy

Hirsutism in women

Loss of fat from adipose tissue

Excess subcuticular fat

Injuries that heal slowly

Injuries that heal slowly

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Neuropathic skeletal disease with bone destruction

Osteoarthritis

Leg pain, neuropathy

Chronic back pain

Muscular wasting

Strain on joints and ligaments

Joint pain

Diminished mobility

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

Increased heart rate

Myocardial hypertrophy

Predisposition to coronary artery disease

High blood pressure

Predisposition to thrombophlebitis

Arteriosclerosis

Peripheral edema

Venous stasis

Varicose veins

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Predisposition to infection

Shortness of breath

Decreased tidal volume

Decreased lung expansion

RENAL SYSTEM

Nephropathy

Vascular changes in kidneys

Increased excretion

Decreased intestinal mobility

Neurogenic bladder

Predisposition to liver and biliary disease

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

Secretion of glucose by liver

NEUROLOGIC SYSTEM

Neuropathy

Sensory impairment

Retinopathy and blindness

ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

Poor or nonexistent insulin production

Predisposition to diabetes mellitus

Poor metabolic control

Pituitary abnormalities

Increased production of cortisol by adrenal glands under stress

Poor metabolic control

Electrolyte imbalance

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Website

Website