The Pathology of Axillary and Intramammary Lymph Nodes

SYED A. HODA

This chapter is devoted to diverse pathologic changes other than metastatic carcinoma that affect the axillary and intramammary lymph nodes. It is, of course, also possible for these lymph nodes to harbor another synchronous disease process in addition to metastatic carcinoma. Additional information about axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) can be found in Chapters 12 and 44 as well as various chapters that discuss the pathology of lymph nodes in relation to specific disease entities.

HETEROTOPIC EPITHELIAL INCLUSIONS

Types of Inclusions

Benign heterotopic epithelial tissue has been found in or associated with lymph nodes at various sites other than the axilla. A frequent example of this phenomenon is inclusion of salivary gland tissue in cervical lymph nodes.1 Heterotopic glandular inclusions (endosalpingiosis) in pelvic and periaortic lymph nodes are derived from pelvic müllerian epithelium and the peritoneum.2,3,4 In the axilla, heterotopic mammary-type glands can appear to be histologically normal except for their aberrant location, or they may develop fibrocystic changes (FCCs), including epithelial hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia, cysts, and sclerosing adenosis (SA). A minority of glandular inclusions in ALNs have müllerianlike features, including microvilli.5 Other inclusions consist of squamous epithelium that is usually cystic, or a mixture of glandular and squamous elements. Heterotopic epithelial inclusions in ALNs are found in the capsule or parenchyma of a lymph node.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Epithelial inclusions have also been found in intramammary lymph nodes,11,17 including those with müllerian-like epithelium.18 Since this patient was found to have a borderline serous carcinoma of the peritoneum 3 years after the intramammary lymph node was excised, the müllerian-like epithelial gland in the lymph node was probably metastatic rather than a benign inclusion.

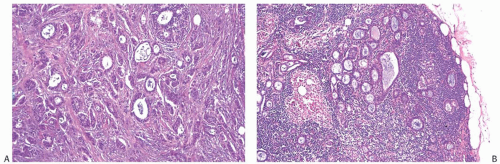

With the exception of heterotopic intranodal inclusions, the finding of orderly glands distributed singly or in small groups within a subcapsular sinus or in the substance of an ALN should be regarded as evidence of metastatic carcinoma. Well-differentiated metastatic carcinoma in ALNs that has been mistakenly diagnosed as glandular heterotopia usually occurs in patients with invasive well-differentiated ductal carcinoma or in patients with intraductal carcinoma who have undergone a needling procedure that results in epithelial displacement.13 Rarely, well-differentiated nodal metastases represent a minor, inconspicuous component of a primary tumor, most of which is histologically different and less well-differentiated (Figs. 43.1 and 43.2). Ohsie et al.19 described an unusual nodal inclusion in a patient with classical invasive lobular carcinoma of one breast. The ipsilateral sentinel lymph node (SLN) contained scattered orderly glands that lacked myoepithelium. Complete sampling of the mastectomy with 366 paraffin blocks failed to uncover an invasive duct carcinoma comparable to the glands in the lymph node. A contralateral mastectomy revealed only FCCs. On the basis of the images provided in this case report, it was not possible to determine whether the glands in the lymph node had müllerian-type epithelium, as might be suspected from the findings as reported.

Histogenesis of Epithelial Inclusions

There is no association between glandular heterotopia and the presence of accessory breast tissue in the axilla.

The histogenesis of glandular heterotopia associated with ALNs is unknown. One hypothesis suggests that heterotopic intranodal epithelium results from isolated cells or fragments of tissue that were displaced by a prior procedure and were transported by lymphatic flow to the lymph node. Since it has been well-documented that epithelial displacement occurs as a result of needle core biopsy procedures (see Chapter 44), this process could explain some cases of nodal heterotopic epithelium. However, the absence of prior procedures in many patients, and the fact that early reports of nodal heterotopia predated the use of needle core biopsies, means that this explanation does not apply in many cases.

Displaced epithelium would not explain the orderly structure of mammary-type glands in which the epithelium is encircled by myoepithelial cells. The latter finding supports the alternative hypothesis that the inclusions derive from epithelial rests that are the result of embryologic maldevelopment.

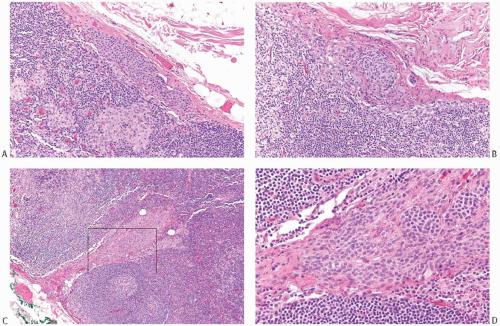

FIG. 43.2. Metastatic carcinoma in the capsule of a sentinel lymph node mistaken for a heterotopic gland inclusion. A,B: The primary tumor had a mixed growth pattern consisting almost entirely of (A) mucinous and (B) classical infiltrating lobular carcinoma. C: Less than 5% of the tumor had this well-differentiated structure. D: Metastatic carcinoma, found only in the capsule and adjacent tissue of this SLN, had well-differentiated glands that were misdiagnosed as heterotopic inclusions. |

However, neither hypothesis provides an explanation for the presence of glands composed of müllerian-like cells in the absence of a demonstrated neoplasm of the female genital tract.

Clinical Presentation

The occurrence of benign heterotopic epithelium in ALNs is rare.20 In a study of autopsy material, no epithelial inclusions were identified in 8,825 slides prepared from 3,904 lymph nodes obtained from 160 postmortem axillary dissections. Each lymph node was grossly cut at 0.2-cm interval, and histologic sections were prepared at 100-µm interval.21

Almost all reported examples of heterotopic epithelial tissue associated with ALNs have occurred in women. Before the era of SLN biopsy, patients with no prior surgery sometimes presented with an axillary mass, but in many instances the affected lymph nodes were clinically inapparent. They were detected in grossly normal lymph nodes removed as part of a surgical procedure. One patient underwent a mastectomy for carcinoma of the left breast 10 years before an enlarged right ALN that contained heterotopic glandular tissue was excised.8 Kadowaki et al.16 described a patient who presented with a 1.8-cm axillary tumor 8 years after she underwent excision of a “nipple adenoma” from the ipsilateral breast. Mammography revealed calcifications in the axillary lesion. When excised after a 2-year delay, the lymph node was found to be extensively involved by a complex, multicystic inclusion with glandular and squamous components.

Since the advent of SLN biopsy of the axilla in women with breast carcinoma, heterotopic epithelial inclusions have received closer scrutiny. Maiorano et al.20 described seven examples of heterotopic epithelial inclusions in axillary SLNs in a total of 3,500 specimens analyzed in a 6-year period. Six of the patients had invasive carcinoma and one had ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), but none had had prior surgery of a needling procedure. Three of the lymph nodes had coincidental metastatic or micrometastatic carcinoma and four had no metastases. In some instances, the heterotopic tissue exhibited proliferative FCCs, including adenosis, duct hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia, and cystic squamous metaplasia. Immunoreactive myoepithelial cells were detected in foci regarded as heterotopic glandular epithelium. As expected, no myoepithelium was found around the cystic squamous inclusions, and the squamous epithelium was immunoreactive for p63.

Gross Pathology

Lymph nodes found to harbor epithelial inclusions are usually grossly unremarkable, but enlarged lymph nodes that measured up to 3 cm have been described in a few instances. Some have contained grossly apparent cysts that were filled with “colorless or brownish fluid,”7 “greenish yellow necrotic-like,”9 or “cottage-cheese-like material.”11 Calcified keratotic debris may be present in cysts lined by squamous epithelium.16

Microscopic Pathology

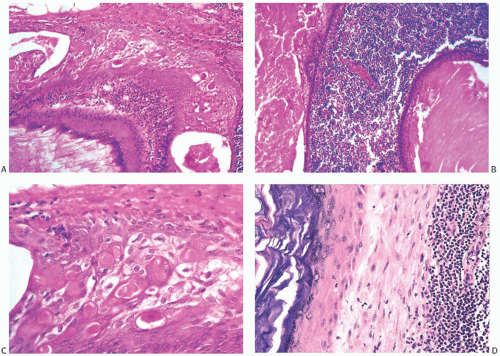

Cystic epithelial inclusions in lymph nodes have been lined by glandular, squamous, or apocrine epithelium6,7,11 (Fig. 43.3). Discharge of keratin from cystic squamous inclusions can elicit a granulomatous reaction.11 Inclusions that appear to be derived from skin appendage glands may exhibit sebaceous differentiation. Proliferative changes in the glandular inclusions have included apocrine metaplasia and duct hyperplasia.20 Heterotopic lobular glands altered by SA involving the capsules and superficial nodal tissue have been reported in two SLNs from a single patient. Myoepithelium was demonstrated in both foci by p63 and CD 10 immunostains. Benign mammary ductal structures are a rare form of heterotopia (Fig. 43.4).

One case report described papillary carcinoma that seemed to arise from a benign intranodal mammary glandular inclusion. This conclusion was based on the observation that some glands associated with the papillary carcinoma in the lymph node appeared to be benign. However, the authors reported that the patient also had in one breast “a small intraductal papillary carcinoma … differing cytologically and architecturally from the nodal carcinoma.” Because of the apparently noninvasive character of the mammary lesions, and differences in the histologic appearance of the two processes, they were regarded as independent lesions, but metastatic involvement of the ALN from the existing mammary papillary carcinoma cannot be ruled out. The possibility that mammary carcinoma could arise from heterotopic glandular inclusions in ALNs is considered more fully in the discussion of occult carcinoma presenting as an axillary nodal metastasis (see Chapter 33).

The distinction between heterotopic mammary glandular epithelium and metastatic carcinoma is usually not difficult (Fig. 43.5). The glandular structures typically occur outside or within the lymph node capsule or in the lymphoid tissue rather than in nodal sinusoids. Myoepithelial cells and specialized intralobular stroma are evident in most heterotopic glands and ducts of the mammary type. On the other hand, they are absent from müllerian-type heterotopic glands and from squamous inclusions. In the absence of myoepithelial cells, glands in ALNs usually represent metastatic carcinoma, even if the growth pattern is extremely well-differentiated. These metastatic foci are typically distributed as isolated glands or small groups of glands in the lymphoid tissue of the lymph node, or in the capsule and subcapsular lymphatic spaces (Figs. 43.1 and 43.2). A collagenous band that resembles a basement membrane may be found around part or all of such metastatic glands. Metastatic tubular carcinoma mistakenly diagnosed as “benign epithelial lined tubules” within a lymph node was illustrated in a published report.22 Histologic identification of ciliated cells and “peg” cells is helpful to recognize the müllerian type of inclusion. Immunoreactivity for Wilms tumor 1 (WT-1) and PAX8 can be used to support the diagnosis.5

NEVUS CELL AGGREGATES

Collections of cells that resemble cutaneous nevi can be found in the capsules of lymph nodes in various areas of the body, including the axilla. Because of their usual association with the lymph node capsule rather than the lymphoid parenchyma in most cases, these groups of cells have been termed “nevus cell aggregates” (NCA), rather than the frequently used term “nevus cell inclusions.”23 A minority of NCA are found within the cortical and medullary lymphoid tissue where they appear to be associated with stromal septa that originate in the capsule.

Etiology

The etiology of NCA is unknown, but it has been suggested that they originate in the lymph node capsule. One investigator has presented evidence of origin from cells in the

walls of vessels in the lymph node capsule.24 This observation is consistent with the view that NCA are angioglomic structures derived from perithelial cells with glomus properties around vessels in the lymph node capsule.25 It has also been hypothesized that NCA arise by a process of “benign metastasis” in which cells are transported (presumably via lymphatic channels) from benign cutaneous nevi to the lymph node. Rarely, these patients have a notable contiguous cutaneous nevus.26 The fact that a few individuals have had prominent nevi or melanomas in the nearby skin suggests that some factor or factors may predispose particular individuals to develop NCA and melanocytic skin lesions. It is not known whether such patients have NCA in nodal areas anatomically unrelated to the known cutaneous lesion because it is not possible to sample lymph nodes at other sites. If NCA were “benign metastases” from clinically inapparent or inconspicuous cutaneous nevi, it is difficult to envision the mechanism by which such “metastases” would almost always be localized to the nodal capsule, since one expects that cellular elements transported via the lymphatics should be deposited in nodal sinuses. The most likely explanation for the histogenesis of NCA is that they are the result of embryologic maldevelopment or that they arise from angioglomic structures that are normally present.

walls of vessels in the lymph node capsule.24 This observation is consistent with the view that NCA are angioglomic structures derived from perithelial cells with glomus properties around vessels in the lymph node capsule.25 It has also been hypothesized that NCA arise by a process of “benign metastasis” in which cells are transported (presumably via lymphatic channels) from benign cutaneous nevi to the lymph node. Rarely, these patients have a notable contiguous cutaneous nevus.26 The fact that a few individuals have had prominent nevi or melanomas in the nearby skin suggests that some factor or factors may predispose particular individuals to develop NCA and melanocytic skin lesions. It is not known whether such patients have NCA in nodal areas anatomically unrelated to the known cutaneous lesion because it is not possible to sample lymph nodes at other sites. If NCA were “benign metastases” from clinically inapparent or inconspicuous cutaneous nevi, it is difficult to envision the mechanism by which such “metastases” would almost always be localized to the nodal capsule, since one expects that cellular elements transported via the lymphatics should be deposited in nodal sinuses. The most likely explanation for the histogenesis of NCA is that they are the result of embryologic maldevelopment or that they arise from angioglomic structures that are normally present.

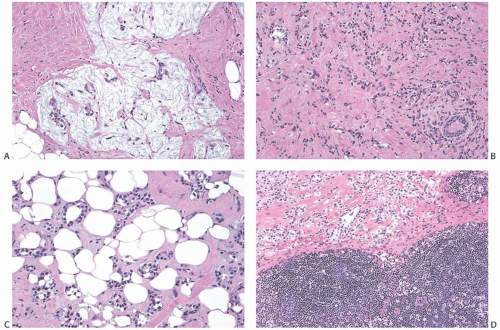

FIG. 43.5. Heterotopic ductal and squamous epithelial tissue associated with axillary lymph nodes. A,B: Two examples of mammary-type ducts in the capsules of lymph nodes. Myoepithelial cells (arrows) are evident around the duct in [A]. Micropapillary hyperplasia is evident in [B]. C: Squamous epithelium-lined cystic inclusion in an SLN. Note the granular cell layer in the epithelium and intracystic keratinous debris. This inclusion was detected on frozen section examination. This photograph is from the frozen section slide that was subsequently destained, and restained for estrogen receptor (ER). The inclusion is ER-negative. The ipsilateral moderately differentiated invasive carcinoma was ER-positive. |

Although NCA have some glomoid structural features, the presence of melanin pigment (verified by electron microscopy) and the existence of heavily pigmented NCA with a blue nevus configuration are indicative of nevocellular differentiation. As discussed in subsequent text, electron microscopy has documented many similarities between the cells of NCA and cutaneous nevi, but it has failed to detect smooth muscle differentiation commonly seen in glomus cells.27 Consequently, it seems more likely that NCA develop from melanocytic cells arrested in migration from the neural crest to the skin, or from primitive neural crestderived cells that may be normally present in the capsules of superficial lymph nodes.28

Frequency

NCA were first described by Stewart and Copeland29 in the hilar region of an ALN obtained from a patient with von Recklinghausen disease, a bathing trunk nevus, and malignant melanoma. Stewart30 commented on three additional axillary NCA in 1960. The first series of six cases was reported by Johnson and Helwig,31 who noted that NCA often contained pigments with the staining properties of melanin. Two of the patients were women who had ALNs removed in the treatment of breast carcinoma, and a third woman had fibrocystic mastopathy. NCA were also found in ALNs obtained from men with basal cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma, and in a cervical lymph node from a man with an epidermal inclusion cyst. Pigmented NCA were subsequently described in an inguinal lymph node from an 8-yearold child with juvenile melanoma,32 and in a cervical lymph node from a man with squamous carcinoma of the larynx.33

In 1974, McCarthy et al.34 described 24 patients who had NCA, including 15 who were treated for malignant melanoma. The majority of NCA were associated with ALNs, but inguinal nodes were affected in seven cases and cervical nodes in two cases. The ages of the patients ranged from 17 to 70 years. The series included four women with axillary NCA who had been treated for breast carcinoma. Pigmented nevi were present in the skin drained by the lymph nodes with NCA in 21 cases. McCarthy et al.34 reported that NCA were present in 6.2% of 129 axillary and in 4.0% of 50 inguinal lymph node dissections. No NCA were found in 130 dissections of thoracic, abdominal, or iliac lymph nodes.

Ridolfi et al.23 reviewed 909 consecutive mastectomy specimens from patients with mammary carcinoma and found a single NCA in each of three cases (0.33%) affecting 0.017% (3 of 17,504) of the lymph nodes examined. One hundred lymph node dissections from patients with malignant melanoma obtained from various sites were also reviewed, yielding NCA in 3 of 2,607 lymph nodes (0.12%). Another study in which lymph nodes were examined by immunohistochemistry as well as routine histology reported that NCA were present in 49 (22%) of 226 lymph node dissections.35 Seventy-eight percent of NCA were detected by routine histology and 22% by staining for S-100 protein. ALNs were the most frequent sites of NCA (22%), followed by cervical (18%) and inguinal (11%) nodes. Bautista et al.36 also used the S-100 stain to study 300 axillary dissections. They reported finding NCA in 7.3% of the specimens and in 0.54% of 5,186 lymph nodes examined.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the foregoing data:

NCA occur in association with superficial lymph node groups that drain the skin as well as other organs. If they ever occur in visceral lymph nodes, it is extraordinarily unusual.

Lymph nodes that contain NCA are most frequent in the axilla and less often found in the groin and cervical regions.

NCA have been detected in lymph nodes from men, women, and children. Most of the patients have had malignant neoplasms, but NCA have been found in lymph nodes from individuals with benign neoplasms and nonneoplastic conditions. They may be more frequent in ALNs from patients with malignant melanoma than in the ALNs of women with mammary carcinoma.

Although some patients with NCA have a contiguous skin lesion such as malignant melanoma or a conspicuous nevus, the majority of these patients have no notable skin lesions.

Clinical Presentation

The majority of NCA are small, often microscopic, structures that do not cause palpable enlargement of lymph nodes or any other clinical symptoms. Consequently, their presence is unsuspected until resected lymph nodes have been examined microscopically after excision. Rare examples of diffuse intranodal NCA have caused grossly evident lymph node enlargement.

Gross Pathology

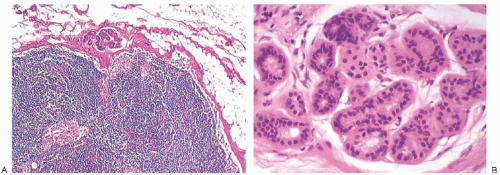

NCA are rarely visible grossly. Heavily pigmented NCA have been described grossly on rare occasions. In one instance, the gross findings suggested anthracotic pigment.37 Another example occurred in an inguinal lymph node removed incidentally during treatment of varicose veins that contained “three darkly pigmented nodules, the largest being 0.3 cm in diameter.”38 A third 0.8-cm lymph node from the axilla of a woman with breast carcinoma contained “a golden-brown crescentic lesion … that occupied approximately one-third of the perimeter”28 (Fig. 43.6). In each of these instances, the microscopic configuration of the NCA was that of a blue nevus.

Microscopic Pathology

Two distinct microscopic patterns of NCA have been described: NCA that resemble intradermal nevi and NCA with the appearance of blue nevi. The former are much more common, with fewer than 10% of NCA having the blue nevus structure. Patients with the two types of NCA do not differ appreciably with respect to age distribution, associated diseases, or the frequency of multinodal involvement.

Intradermal Nevus Type of NCA

NCA of the intradermal nevus type have a flat or nodular configuration in the lymph node capsule (Fig. 43.7). In most cases, a single lymph node is affected, but in rare instances NCA are found in two or more lymph nodes from a nodal group.25,31,39,40,41 In a single plane of section, nevus-type NCA occupy a fraction of the perimeter of a lymph node. They often appear to have a discontinuous distribution and may extend into the node itself usually along fibrous trabeculae. Any portion of the capsule may be affected, and there does not seem to be a predilection to involve the hilar region. Rarely, these NCA lie entirely within the lymphoid parenchyma of the lymph node.23,36,42 Nevus-type NCA have not been encountered as isolated structures in the peripheral sinus of a lymph node.

The architecture of nevus-type NCA is demonstrated in sections prepared with the reticulin stain. The cells that form an NCA are cytologically very similar to cells of an ordinary intradermal nevus. They tend to be tightly clustered into defined masses separated by, or sometimes seemingly centered about, thin-walled capillaries. When they have a particularly angular configuration, these capillaries may be mistaken for artifactual spaces. The outer, peripheral portion of nevustype NCA is usually sharply defined, whereas at the inner margin NCA cells may merge with capsular tissue.

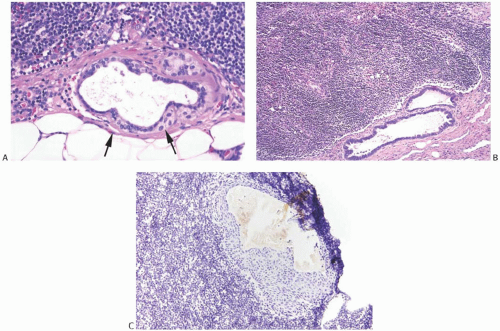

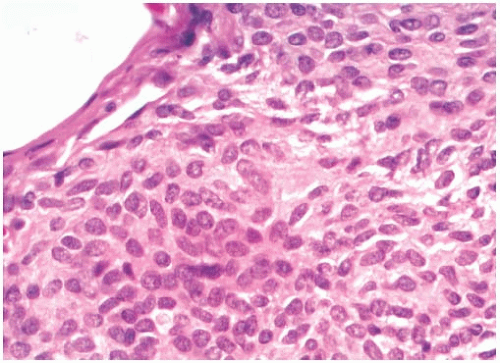

Cytologically, nevus-type NCA cells are typically oval or spindle-shaped with indistinct cytoplasmic borders (Fig. 43.8). Polygonal or epithelioid cells are found in some cases. The central nuclei have fine, diffuse chromatin and are surrounded by pale or clear cytoplasm. Nucleoli are small and indistinct or absent. Intranuclear inclusions may be evident. Mitoses are not seen, and less than 1% of the cells express Ki67.42 Multinucleated cells of the type sometimes found in intradermal nevi are not a feature of nevus-type NCA.

Fine brown pigment granules can be detected in the cytoplasm of a few scattered cells in a minority of NCA. This pigment gives a negative Perls Prussian blue reaction for iron, and it is blackened with the Fontana Masson and Grimelius stains, indicating the presence of melanin (Fig. 43.9). NCA contain no mucin when studied with mucicarmine, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), or Alcian blue stains. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed strong reactivity for S-100 protein and MART1/MelanA, but not for HMB45.42 There is also absence of staining for cytokeratin (CK), hormone receptors, or epithelial membrane antigen (Fig. 43.10).

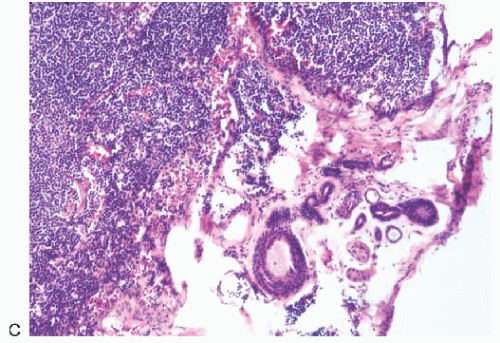

Blue Nevus Type of NCA

NCA of the blue nevus variety have poorly defined borders. These heavily pigmented lesions, which occupy the lymph node capsule and radiate into surrounding fat, may also extend into the nodal lymphoid tissue28,37,38,43 (Fig. 43.11). The finely granular pigment is golden or dark brown. It fills and often obscures the cytoplasm of many cells in the lesion, especially the closely packed elongated cells with dendritic processes. At the outer, peripheral edges of blue nevus type of NCA, these slender cells extend into the perinodal fat. It is unusual for blue nevus type of NCA to extend along trabeculae into the substance of a lymph node. Scattered singly and in small groups among the spindle cells are polygonal cells with pale cytoplasm that contains coarsely clumped pigment. These epithelioid cells resemble pigmented histiocytes. Blue nevus-type NCA differ from nevus-type NCA in being immunoreactive for HMB45.44 They are also immunoreactive for S-100 protein and MART1/MelanA. Mitotic figures and multinucleated giant cells are absent from the blue nevus type of NCA.

Differential Diagnosis

Because the indication for a lymph node dissection is almost always a regional malignant neoplasm, it is important that NCA not be mistakenly interpreted as metastatic tumor.45 The deceptively bland histologic appearance of some melanoma metastases can simulate an NCA. Since NCA as well as most melanomas express S-100 and MART1/MelanA, these stains are not helpful in the differential diagnosis. However, melanoma has a high percentage of Ki67-positive cells, whereas less than 1% of cells in NCA are Ki67-positive. When uncertainty persists, fluorescence in situ

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree