Carcinoma with Metaplasia and Low-Grade Adenosquamous Carcinoma

EDI BROGI

CARCINOMA WITH METAPLASIA

Because carcinoma of the breast arises from the mammary glandular epithelium, it usually exhibits the features of adenocarcinoma. However, in less than 5% of mammary carcinomas, some or all of the neoplastic cells acquire nonglandular morphology and growth pattern, evidence of a process known as metaplasia (from the Greek verb metaplasein = to mold into a new form), meaning the change of one cell type into another. Lecene1 provided the first description of a carcinoma resembling metaplastic carcinoma in 1906. One of the earliest studies of mammary metaplastic carcinoma was published by Huvos et al.2 in 1973.

Benign Metaplasia

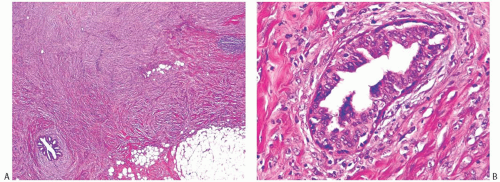

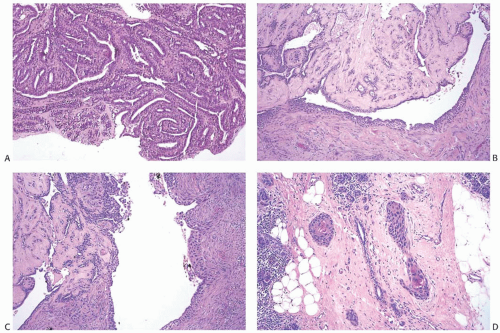

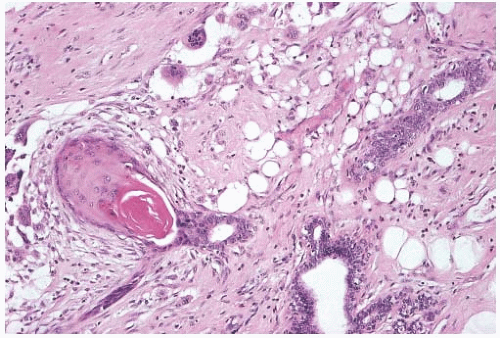

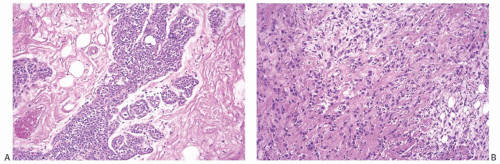

Apocrine change is by far the most common forms of metaplastic change involving the mammary glandular epithelium. Squamous metaplasia can be present in the glandular epithelium of benign breast neoplasms such as papillomas and fibroadenomas, and may occur in nonneoplastic epithelial proliferations, as in benign cysts and gynecomastia. Raju3 described squamous metaplasia that arose in hyperplastic myoepithelial cells in a fibroadenoma. Immunoreactivity for actin and vimentin was present in myoepithelial and squamous metaplastic cells, but not in normal epithelial cells. Illustrations in this case report provide convincing evidence of transition from myoepithelial to squamous cells in a benign lesion. Reparative epithelium in ducts or lobules may undergo squamous metaplasia at a healing site (Fig. 16.1).

Heterologous osseous or chondroid metaplasia may be found in radial sclerosing lesions, adenomyoepitheliomas (AMEs), sites of old fat necrosis, and, rarely, in apparently normal fatty breast tissue.4 Chondroid and osseous metaplasia occurring in a sclerosing papilloma results in a lesion that resembles mixed tumor of the salivary glands. Chondroid, adipose, or osseous metaplasia is also very rarely encountered in the stroma of fibroadenomas.

Malignant Metaplasia

Among malignant mammary neoplasms, the term “metaplasia” has traditionally been reserved for tumors that exhibit microscopic structural changes that diverge from glandular differentiation, such as squamous, spindle cell, chondroid, and osseous morphology. These phenotypic alterations are the expression of genotypic properties that are not typical of normal mammary epithelial and myoepithelial cells, but result from a process of genetic dedifferentiation. The scientific term used for this phenomenon is “epithelial to mesenchymal transition” (EMT). (See subsequent section on genetics and molecular studies.)

The extent of metaplastic changes in breast carcinomas varies from isolated microscopic foci in an otherwise typical mammary carcinoma, to complete replacement of glandular growth by the metaplastic phenotype. The frequency of metaplastic change in mammary carcinoma is probably underreported because inconspicuous foci are easily overlooked or

ignored. This limitation applies especially to spindle and squamous metaplasia. Heterologous components such as bone and cartilage seem to engender greater interest and are more likely to be noted. Fisher et al.5 found squamous metaplasia in 3.6% of invasive carcinomas. Kaufman et al.6 detected heterologous metaplasia in 26 (0.2%) of 12,045 breast carcinomas. Carcinomas with large central acellular zones of necrosis (also known as centrally necrotizing carcinoma) have an area of myxoid/chondroid metaplasia interposed between the necrotic/fibrotic center and the peripheral hypercellular ring of viable high-grade carcinoma.7,8 Metaplastic changes occur more often in poorly differentiated duct carcinomas, but they may be found rarely in other types of carcinoma, including invasive lobular carcinoma and papillary tumors.

ignored. This limitation applies especially to spindle and squamous metaplasia. Heterologous components such as bone and cartilage seem to engender greater interest and are more likely to be noted. Fisher et al.5 found squamous metaplasia in 3.6% of invasive carcinomas. Kaufman et al.6 detected heterologous metaplasia in 26 (0.2%) of 12,045 breast carcinomas. Carcinomas with large central acellular zones of necrosis (also known as centrally necrotizing carcinoma) have an area of myxoid/chondroid metaplasia interposed between the necrotic/fibrotic center and the peripheral hypercellular ring of viable high-grade carcinoma.7,8 Metaplastic changes occur more often in poorly differentiated duct carcinomas, but they may be found rarely in other types of carcinoma, including invasive lobular carcinoma and papillary tumors.

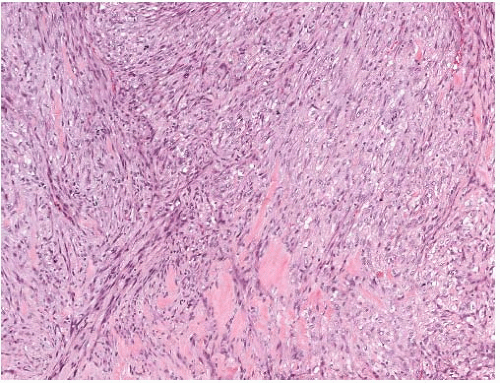

FIG. 16.1. Squamous metaplasia in reparative epithelium. Squamous metaplasia is present in the duct on the left in this healing biopsy site. |

The confusing terminology used in the past to describe metaplastic carcinomas reflects the uncertainty about their histogenesis. Some lesions have been described as “mixed tumors,” an unfortunate reference to tumors of the salivary glands that are predominantly benign.9 Others have referred to metaplastic carcinomas as carcinosarcomas.10 This term should be reserved for malignant neoplasms in which the carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements can be traced separately to epithelial and mesenchymal origins. True carcinosarcomas are extremely rare, if indeed they truly exist. In at least one case of invasive ductal carcinoma arising in a high-grade malignant phyllodes tumor (PT), the malignant epithelial and stromal components shared loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the same regions of chromosomes 4, 11, 13, 17, and 21, in addition to other individual alterations, suggesting origin from a common precursor.11 It has also been suggested that metaplastic carcinomas with minimal or no invasive carcinomatous component should be classified and managed as sarcomas or pseudosarcomas,12 but this concept is not supported by histogenetic or immunohistochemical evidence.

There are no established criteria regarding the extent of metaplasia required to diagnose metaplastic carcinoma, and the extent of metaplastic component can range from about 10% to 100% of the tumor mass. Whether a carcinoma is classified as metaplastic or only as having metaplastic features, it is very important to always mention the presence and type of any metaplasia, independent of its extent.

The term “myoepithelial carcinoma” has been used for mammary spindle cell carcinomas showing myoepithelial differentiation.13 Evidence discussed later in this chapter indicates that metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas display the myoepithelial or basal cell-like immunophenotype seen in the so-called myoepithelial carcinoma, making use of the latter term confusing and unnecessary.

Evidence of epithelial differentiation in a tumor with entirely or almost entirely metaplastic morphology includes identification of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and/or focal invasive carcinoma with usual morphology, and/or positive immunoreactivity for keratin and/or myoepithelial markers. Precise subclassification of carcinomas with metaplasia is rendered impractical by the extreme morphologic heterogeneity of these lesions and by the difficulty in quantifying the different morphologic components present in each tumor. A broad distinction is usually drawn between carcinomas with squamous and/or spindle cell metaplasia and carcinomas with heterologous component, such as chondromyxoid and/or osseous matrix. Metaplastic low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma (LGASC), however, shows characteristic morphology and clinical behavior and needs to be distinguished from all other metaplastic carcinomas. LGASC is discussed separately at the end of this chapter.

Clinical Presentation

Metaplastic breast carcinomas are rare tumors. Although the precise incidence is difficult to establish, 892 metaplastic carcinomas identified in the National Cancer Data Base14 amounted to 0.24% of 365,464 breast malignant tumors diagnosed during a 3-year period (2001 to 2003), compared with 69.8% invasive ductal carcinomas.

Metaplastic carcinoma typically affects women. To the best of our knowledge, only one series has documented a case of metaplastic carcinoma in a male patient.15 A tumor reported as triple negative metaplastic mammary carcinoma in a Pakistani male likely did not primarily arise in the breast parenchyma, as the main tumor mass appears to be too lateral in the chest wall in the image that was provided.16

The age range at diagnosis is similar to that of nonmetaplastic carcinomas, but women of perior postmenopausal age tend to be affected more commonly.2,6,12,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 The mean age at diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma was 61.1 years in one study,14 with 13.5% of cases occurring in women older than 80 years and 7.8% in women younger than 40 years. About 72% to 81%14,26 of metaplastic carcinomas occur in White women, 12% to 14% in women of African American ethnicity,14,26 and 5%14,32 to 11%26 in women of Hispanic descent. Rare cases of metaplastic carcinoma have been reported in BRCA1 germline mutation carriers, including two cases with biphasic epithelial and sarcomatoid morphology39,40 and two with chondroid metaplasia.31 Chondroid metaplasia was also present in an atypical medullary carcinoma in a woman with BRCA1 germline mutation.41

The initial clinical presentation of a metaplastic carcinoma is typically as a palpable mass showing rapid growth over a short period of time.18 Large lesions can be complicated by fixation to the skin or chest wall and skin ulceration.20,42 Most tumors are unilateral, but one patient with bilateral metaplastic carcinoma has been described.6 Reports of nipple discharge associated with a mass lesion are exceedingly rare.43

Imaging Studies

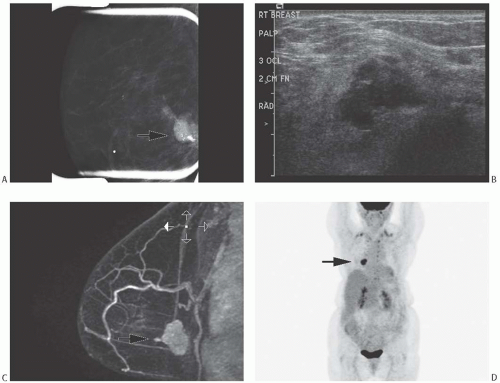

Choi and Shu36 conducted a detailed radiologic analysis of 33 metaplastic carcinomas. The most common mammographic findings included high density (74%), circumscribed margins (59%), and oval shape (37%). Microcalcifications were present in 7 of 33 (23%) cases and were pleomorphic in 5 cases and linear or round in one case each. In some instances, calcifications may be present in DCIS rather than in the invasive metaplastic carcinoma. Mammography can also detect calcified areas in tumors with chondroid and osseous metaplasia42,44,45 (Fig. 16.2). On sonographic examination, metaplastic carcinomas had a parallel orientation (97%),

complex echogenicity (81%), irregular shape (59.4%), posterior acoustic enhancement (50%), and a microlobulated margin (41%)36 (Fig. 16.2). The most common magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings included an irregular heterogeneous enhancing mass (Fig. 16.2), with irregular shape (52.4%) and margin (57%), and high T2-weighted signal intensity (57%).36 The latter feature has been correlated with the presence of necrosis44 and with chondroid areas.45 Choi and Shu36 found heterogeneous internal enhancement in 71% of cases of metaplastic carcinoma, with delayed washout pattern on kinetic curve analysis in 67% of cases. Intense uptake of technetium 99m-methylene diphosphonate was observed in mammary carcinomas with osseous sarcomatoid metaplasia.45,46,47 The tumors are highly metabolic on F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) (Fig. 16.2).

complex echogenicity (81%), irregular shape (59.4%), posterior acoustic enhancement (50%), and a microlobulated margin (41%)36 (Fig. 16.2). The most common magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings included an irregular heterogeneous enhancing mass (Fig. 16.2), with irregular shape (52.4%) and margin (57%), and high T2-weighted signal intensity (57%).36 The latter feature has been correlated with the presence of necrosis44 and with chondroid areas.45 Choi and Shu36 found heterogeneous internal enhancement in 71% of cases of metaplastic carcinoma, with delayed washout pattern on kinetic curve analysis in 67% of cases. Intense uptake of technetium 99m-methylene diphosphonate was observed in mammary carcinomas with osseous sarcomatoid metaplasia.45,46,47 The tumors are highly metabolic on F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) (Fig. 16.2).

FIG. 16.2. Metaplastic carcinoma, imaging studies. All images are of the same metaplastic carcinoma in the right breast of a 66-year-old woman with history of ipsilateral invasive ductal carcinoma 20 years earlier treated with conservation therapy and contralateral invasive ductal carcinoma diagnosed 1 year earlier. Metaplastic carcinoma was a new independent primary carcinoma in the right breast. A: Spot compression mammographic view in the mediolateral oblique projection demonstrates a 2.6-cm high-density, irregular mass with coarse and pleomorphic calcifications in the posterior right breast. B: The sonogram shows an irregular, indistinct, and hypoechoic mass in the right breast with internal echogenic foci representing calcifications. C: The subtracted T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrates an irregular heterogeneously enhancing mass in the posterior breast near the chest wall. D: A maximal intensity projection image from F18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scan reveals intense hypermetabolism in the tumor (arrow) and an otherwise normal physiologic distribution of radiotracer. (All images courtesy of Kimberly Feigin M.D., Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.) |

Gross Pathology

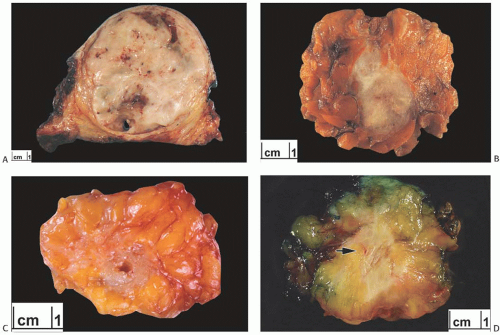

The reported size of metaplastic mammary carcinomas ranges from 0.5 to 24 cm.2,6,12,14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,31,34,48 The mean or median sizes (3 to 4 cm) in various series tend to be greater

than those of ordinary carcinomas, including triple negative breast carcinomas.35 In one study, the median size of metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas and of carcinomas with areas of spindle cell metaplasia were 5.2 and 5.5 cm, respectively, and both measurements were substantially larger than the median size of all metaplastic carcinomas combined (3.7 cm).23 In the study by Pezzi et al.,14 29.5% of 892 metaplastic carcinomas were T1 tumors, 49.6% T2 tumors, and 20.4% were T4 tumors. The majority of tumors are described as firm to hard, nodular, and circumscribed, but some lesions have infiltrative borders (Fig. 16.3). Degenerated cystic areas can be encountered, especially in tumors with squamous metaplasia.18,49 Hemorrhagic areas can be seen in metaplastic carcinomas with choriocarcinomatous morphology, as well as in tumors with abnormal vascularity (Fig. 16.4).

than those of ordinary carcinomas, including triple negative breast carcinomas.35 In one study, the median size of metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas and of carcinomas with areas of spindle cell metaplasia were 5.2 and 5.5 cm, respectively, and both measurements were substantially larger than the median size of all metaplastic carcinomas combined (3.7 cm).23 In the study by Pezzi et al.,14 29.5% of 892 metaplastic carcinomas were T1 tumors, 49.6% T2 tumors, and 20.4% were T4 tumors. The majority of tumors are described as firm to hard, nodular, and circumscribed, but some lesions have infiltrative borders (Fig. 16.3). Degenerated cystic areas can be encountered, especially in tumors with squamous metaplasia.18,49 Hemorrhagic areas can be seen in metaplastic carcinomas with choriocarcinomatous morphology, as well as in tumors with abnormal vascularity (Fig. 16.4).

Microscopic Pathology

Histologic examination of the excised tumor is required for the definitive diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma. It has been customary to subdivide metaplastic carcinomas into two categories: carcinomas with squamous and/or spindle cell metaplasia and carcinomas with heterologous metaplasia that have a mesenchymal phenotype, including chondroid and osseous metaplasia. This distinction is not applicable to all metaplastic carcinomas because some tumors exhibit more than one type of growth. The most common combined configuration includes squamous and undifferentiated spindle cell areas, sometimes with a storiform pattern.20,50,51 Chondroid or osseous metaplasia rarely coexists with squamous metaplasia.52

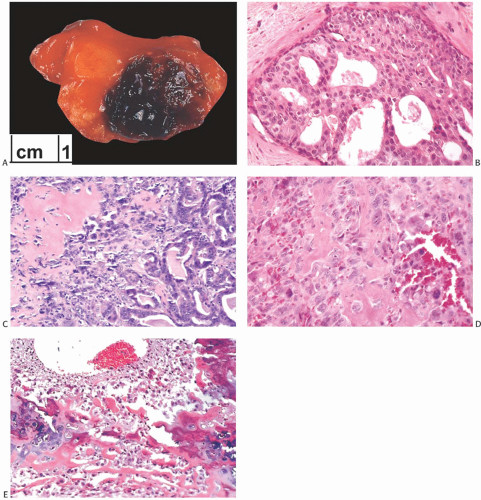

DCIS is present adjacent to metaplastic carcinoma in 11%6 to 65%17 of cases and usually, but not always, has high or intermediate nuclear grade (Figs. 16.4 and 16.5). The presence of DCIS strongly supports the diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma. Rarely, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) can be present.

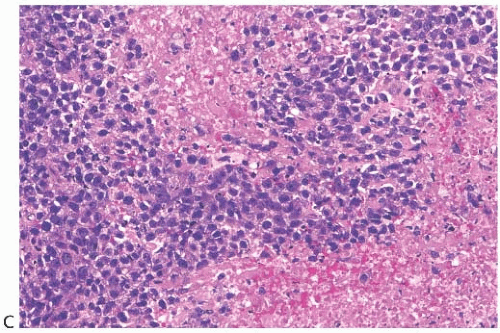

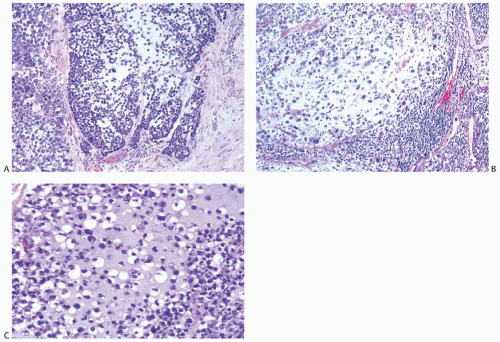

Chronic inflammation is often present both at the periphery of metaplastic carcinomas and dispersed within the neoplasm (Fig. 16.6). A moderate inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of mature lymphocytes is especially common in carcinomas with squamous and spindle cell metaplasia, but

is also found in carcinomas with heterologous elements. This is such a frequent feature that a diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma should rarely be made when little or no inflammation is present.

is also found in carcinomas with heterologous elements. This is such a frequent feature that a diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma should rarely be made when little or no inflammation is present.

Spindle Cell Metaplastic Carcinomas (with or without Squamous Metaplasia)

Metaplastic carcinomas with spindle cell (with or without squamous metaplasia) may show a variety of histologic appearances, depending on the proportions of the spindle cell and squamous components. The terminology used here to refer to these tumors is purely descriptive, but it is helpful to summarize their morphologic features. Metaplastic carcinomas consisting entirely of squamous metaplasia are discussed in Chapter 17.

Metaplastic Carcinoma with Spindle Cell Metaplasia (Intermediate or High Grade)

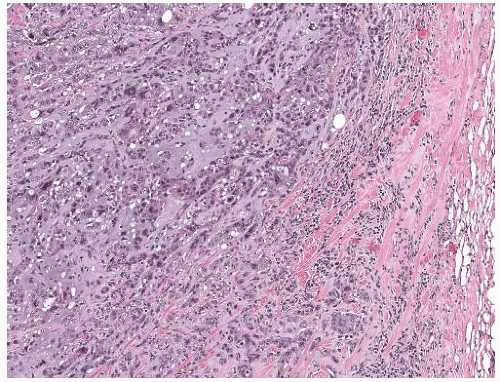

These tumors are a subset of carcinomas in which most or all of the neoplasm has assumed a pseudosarcomatous, spindle cell growth pattern that resembles fibrosarcoma.18,51,53 In the

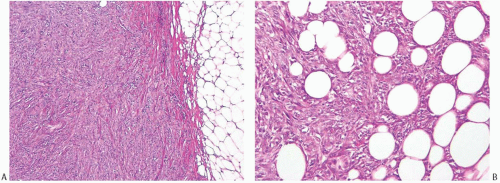

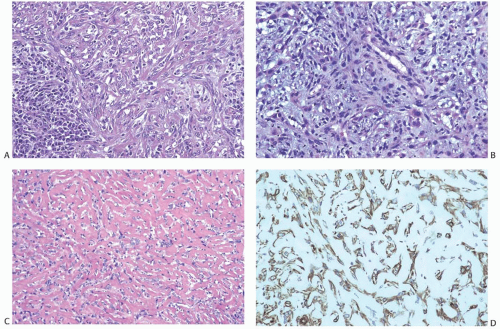

latter instance, the distinction between spindle cell carcinoma and primary sarcoma of the breast can be difficult, and the neoplasm might be mistaken for fibrosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) because of the minimal epithelial component and a storiform growth pattern (Fig. 16.7).20,52 The tumor border can be infiltrative or pushing (Fig. 16.8). These lesions usually show moderate to high cellularity. The neoplastic spindle cells have moderate- to high-grade nuclear atypia. Mitoses are easily identified and usually numerous. Large areas of necrosis may be present, especially in cellular tumors with high nuclear grade (Fig. 16.9). Extensive sampling sometimes identifies focal areas of squamous differentiation (Fig. 16.10) or foci of DCIS (Figs. 16.4 and 16.5) or invasive adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), but in most cases the invasive tumor shows no obvious epithelial elements. If present, squamous foci tend to be located at the tumor periphery. All histologic, immunohistochemical, and clinical features of a lesion must be taken into consideration to distinguish spindle cell metaplastic carcinoma from sarcoma, whether primary in the breast or metastatic from another site. Metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma of the breast typically grows in between nonneoplastic ducts and lobules, entrapping native mammary epithelial elements within the tumor, especially at its periphery (Fig. 16.11). This growth pattern differs from that of a metastatic spindle cell neoplasm of extramammary origin, as the latter typically destroys the mammary epithelial structures, without entrapping them. Rarely DCIS is present admixed with metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma.54 Carter et al.54 found DCIS in 4/29 (14%) cases. More commonly, the residual mammary ducts at the periphery of the lesion show gynecomastoid ductal hyperplasia of the usual type (Fig. 16.11).

latter instance, the distinction between spindle cell carcinoma and primary sarcoma of the breast can be difficult, and the neoplasm might be mistaken for fibrosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) because of the minimal epithelial component and a storiform growth pattern (Fig. 16.7).20,52 The tumor border can be infiltrative or pushing (Fig. 16.8). These lesions usually show moderate to high cellularity. The neoplastic spindle cells have moderate- to high-grade nuclear atypia. Mitoses are easily identified and usually numerous. Large areas of necrosis may be present, especially in cellular tumors with high nuclear grade (Fig. 16.9). Extensive sampling sometimes identifies focal areas of squamous differentiation (Fig. 16.10) or foci of DCIS (Figs. 16.4 and 16.5) or invasive adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), but in most cases the invasive tumor shows no obvious epithelial elements. If present, squamous foci tend to be located at the tumor periphery. All histologic, immunohistochemical, and clinical features of a lesion must be taken into consideration to distinguish spindle cell metaplastic carcinoma from sarcoma, whether primary in the breast or metastatic from another site. Metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma of the breast typically grows in between nonneoplastic ducts and lobules, entrapping native mammary epithelial elements within the tumor, especially at its periphery (Fig. 16.11). This growth pattern differs from that of a metastatic spindle cell neoplasm of extramammary origin, as the latter typically destroys the mammary epithelial structures, without entrapping them. Rarely DCIS is present admixed with metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma.54 Carter et al.54 found DCIS in 4/29 (14%) cases. More commonly, the residual mammary ducts at the periphery of the lesion show gynecomastoid ductal hyperplasia of the usual type (Fig. 16.11).

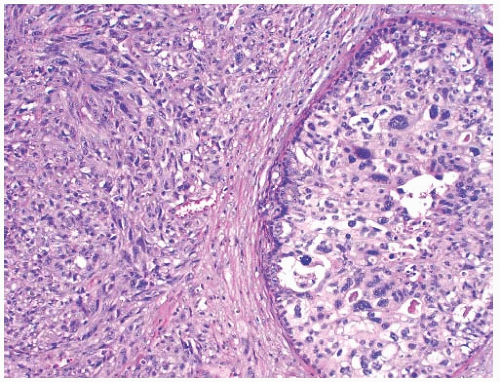

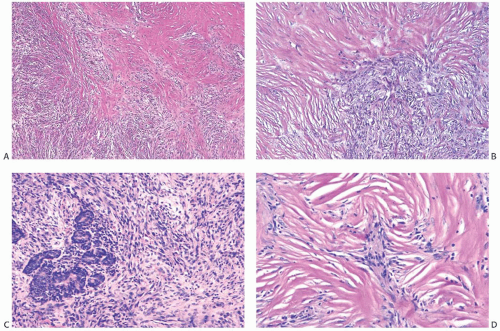

Metaplastic Spindle Cell Carcinoma with “Low-Grade” or “Fibromatosis-Like” Pattern

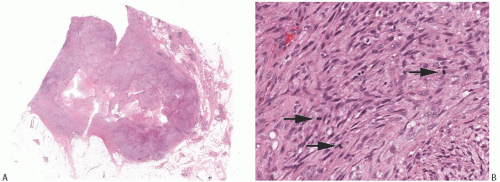

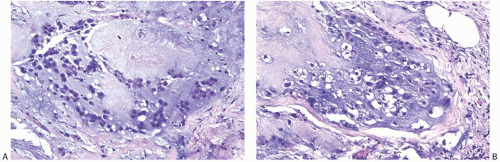

Some metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas have dense, keloidlike areas of fibrosis in which the spindle cells display a storiform pattern (Fig. 16.12). Tumor cellularity is heterogeneous. Closely juxtaposed hypercellular and hypocellular areas are admixed with areas of collagenous fibrosis that can be extensive and deceivingly hypocellular or nearly acellular, especially in the center of the tumor. The neoplastic cells are organized in short interlacing fascicles with haphazard arrangement (Fig. 16.13). The cells tend to be inconspicuous and have ill-defined cell borders, no obvious cytoplasm, and elongated nuclei. Focally, the spindle cells display epithelioid morphology and have slightly more abundant and/or denser cytoplasm. The cells often line up, forming short arrays and chords that may superficially resemble small blood vessels,

but are not associated with red blood cells. These epithelioid foci usually display positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (CKs). Tissue sections containing these areas should be actively selected for immunohistochemical analysis, as CK positivity can be focal (Fig. 16.13). Closer examination discloses atypical cells characterized by nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia. The nuclear atypia is usually focal and never of high grade. Mitotic activity tends to be low, ranging from less than two mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs) in most cases to three to five mitoses per 10 HPFs.50,55 Atypia and mitoses are more obvious in the cellular areas. Foci of chronic inflammation are scattered throughout the carcinoma and at its periphery. In some cases, inflammation can be extensive and nearly mask the true nature of the tumor, raising the differential diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumor or fasciitis. The latter lesions are very infrequent in the breast, and a tumor suggesting mammary fasciitis or inflammatory pseudotumor almost invariably proves to be metaplastic carcinoma. If invasive carcinoma with epithelial morphology is present, this should not represent more than 5% of the tumor mass.50,55 Associated invasive epithelial carcinoma needs to have lowgrade cytologic atypia50,55 (Fig. 16.14) and can consist of invasive lobular carcinoma22 (Fig. 16.15). Rarely, focal low-grade squamous morphology can be appreciated (Figs. 16.16 and 16.17). The ducts admixed with type of metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma may harbor low-grade DCIS,50,55 LCIS,55 (Fig. 16.15), or ADH,22,50 but often show mild ductal hyperplasia of the gynecomastoid type, devoid of atypia.

but are not associated with red blood cells. These epithelioid foci usually display positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (CKs). Tissue sections containing these areas should be actively selected for immunohistochemical analysis, as CK positivity can be focal (Fig. 16.13). Closer examination discloses atypical cells characterized by nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia. The nuclear atypia is usually focal and never of high grade. Mitotic activity tends to be low, ranging from less than two mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs) in most cases to three to five mitoses per 10 HPFs.50,55 Atypia and mitoses are more obvious in the cellular areas. Foci of chronic inflammation are scattered throughout the carcinoma and at its periphery. In some cases, inflammation can be extensive and nearly mask the true nature of the tumor, raising the differential diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumor or fasciitis. The latter lesions are very infrequent in the breast, and a tumor suggesting mammary fasciitis or inflammatory pseudotumor almost invariably proves to be metaplastic carcinoma. If invasive carcinoma with epithelial morphology is present, this should not represent more than 5% of the tumor mass.50,55 Associated invasive epithelial carcinoma needs to have lowgrade cytologic atypia50,55 (Fig. 16.14) and can consist of invasive lobular carcinoma22 (Fig. 16.15). Rarely, focal low-grade squamous morphology can be appreciated (Figs. 16.16 and 16.17). The ducts admixed with type of metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma may harbor low-grade DCIS,50,55 LCIS,55 (Fig. 16.15), or ADH,22,50 but often show mild ductal hyperplasia of the gynecomastoid type, devoid of atypia.

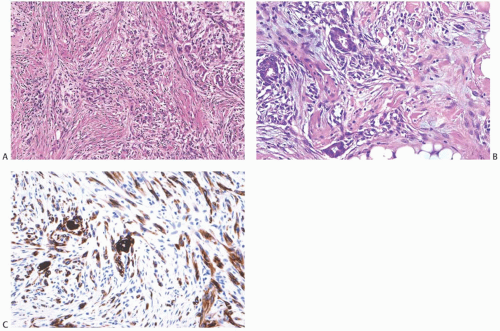

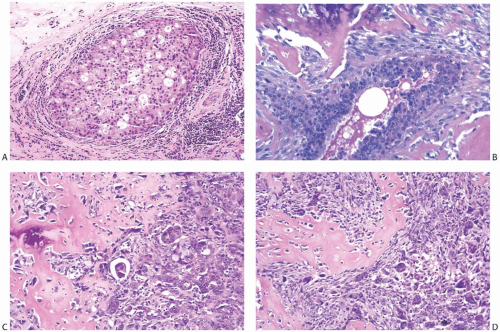

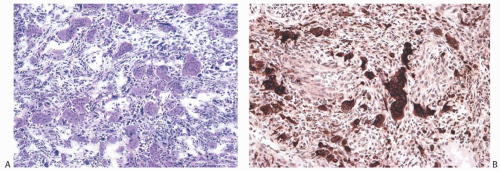

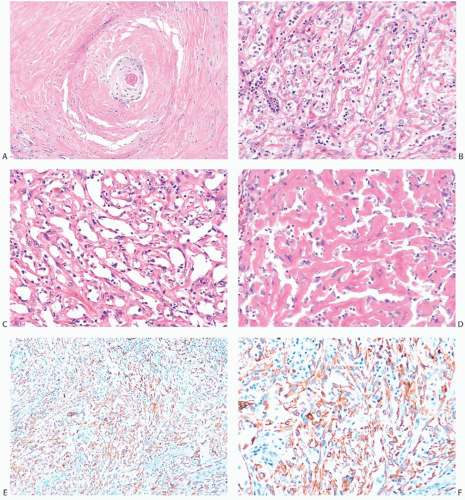

FIG. 16.15. Metaplastic carcinoma, spindle cell type with invasive lobular carcinoma. All images are from the same specimen. A:LCIS in a duct and lobular glands. B: Invasive lobular carcinoma, classical type. C: Spindle cell metaplastic carcinoma with focal squamous differentiation. D: Pseudoangiomatous metaplastic growth pattern. |

Metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas with deceptively bland morphology have been described in association with papillomas55,56 (Fig. 16.18), complex sclerosing lesions (CSLs), and nipple adenomas.57,58 In these cases, presenting symptoms may include a mass lesion and/or nipple discharge.57 Metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas with this morphology are referred to as “fibromatosis-like”50 or “low-grade.”55 Despite having relatively bland morphology, these neoplasms are malignant and can metastasize to distant sites, especially to the lungs, and few patients have died of disease.22,54,55 Nonetheless, metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas with “low-grade” “fibromatosis-like” morphology seem to be not as rapidly aggressive as metaplastic spindle cell carcinomas with intermediate- or high-grade morphology.

Metaplastic Carcinoma with Pseudoangiomatous/ Acantholytic Pattern

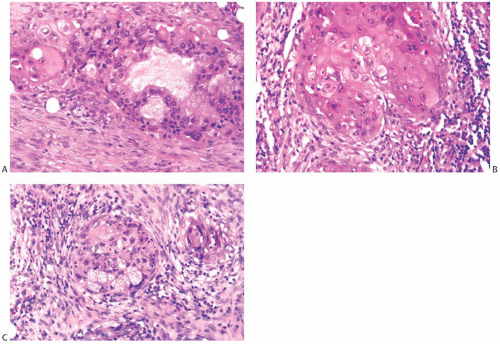

An unusual variant of mammary carcinoma with spindle and squamous metaplasia has been characterized as pseudoangiomatous or acantholytic carcinoma.59,60,61 The acantholytic

appearance is due to degeneration of the neoplastic epithelial component embedded in abundant spindle cell stroma (Fig. 16.19), resulting in a pattern of complex anastomosing pseudovascular spaces62 (Fig. 16.20). The cells lining these spaces are immunoreactive for CKs and do not stain for factor VIII or CD34. Spindle cell and acantholytic variants of metaplastic carcinoma are almost always immunoreactive with the high molecular weight CK 34βE12 (K903) (Figs. 16.19 and 16.20), even when other CK markers are negative. Positive reactivity for CK5, a basal CK, has also been reported.61

appearance is due to degeneration of the neoplastic epithelial component embedded in abundant spindle cell stroma (Fig. 16.19), resulting in a pattern of complex anastomosing pseudovascular spaces62 (Fig. 16.20). The cells lining these spaces are immunoreactive for CKs and do not stain for factor VIII or CD34. Spindle cell and acantholytic variants of metaplastic carcinoma are almost always immunoreactive with the high molecular weight CK 34βE12 (K903) (Figs. 16.19 and 16.20), even when other CK markers are negative. Positive reactivity for CK5, a basal CK, has also been reported.61

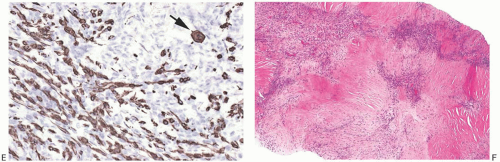

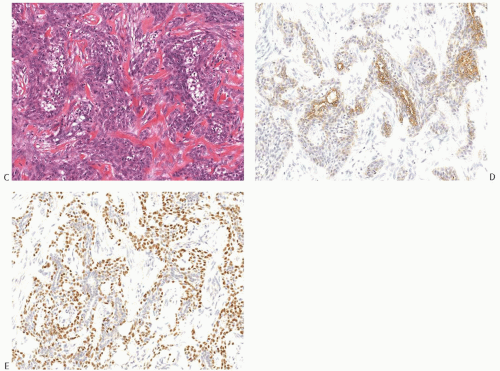

Metaplastic High-Grade Adenosquamous Carcinoma

A common pattern of metaplastic carcinoma is focal squamous metaplasia in an otherwise typical invasive ductal carcinoma (Fig. 16.21). When squamous metaplasia is the predominant pattern, a spectrum of differentiation may be found. Mature keratinizing epithelium, sometimes with keratohyaline granules, as well as adenocarcinoma can be associated with transitions to spindle cell, pseudosarcomatous areas. In unusual instances, the adenocarcinomatous component mingles with the metaplastic carcinomatous epithelium, sometimes with a pagetoid distribution. The term “high-grade adenosquamous carcinoma” is often used for tumors showing both squamous and glandular components with moderate to high cellularity and nuclear atypia (Fig. 16.22), in contrast to LGASC that is described at the end of this chapter. Mitotic activity is usually moderate to high, and areas of necrosis may be present.

Differential Diagnosis of Metaplastic Carcinoma with Spindle Cells (with or without Squamous Morphology)

The differential diagnosis of metaplastic carcinoma with spindle cells (with or without squamous morphology) includes PT, fibrosarcoma, and high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma. The differential diagnosis of “low-grade” metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma includes fibromatosis and nodular fasciitis.

The presence of leaf-like fronds lined by glandular epithelium is characteristic of PT. Occasionally, stromal cells in PT may show focal positivity for CK,63 and this finding can be misleading, especially when only limited material is available for diagnosis. Even in the presence of focal CK staining in needle core biopsy material, a malignant lesion with exclusively spindle cell morphology and no overt epithelial component or frond-like architecture should always be classified with caution, including metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma and high-grade malignant PT in the differential diagnosis. The identification of a rare stromal frond focally lined by epithelium can be the only evidence differentiating a high-grade malignant PT from a metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma. The differential diagnosis of these two lesions has important implications for clinical management, and patient prognosis also varies greatly, depending on the diagnosis.

FIG. 16.20. Metaplastic carcinoma, acantholytic. A: Well-differentiated metaplastic squamous carcinoma surrounded by densely collagenous tissue that is part of the neoplastic process. B: Part of the tumor in which the carcinoma forms a trabecular pattern. There is a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered degenerating tumor cells are represented by pyknotic nuclei. C: Extensive degeneration of the carcinoma resulting in an angiomatous appearance. D: Dense stroma in angiomatous metaplastic carcinoma. E: Diffuse immunoreactivity for CK AE1:3. F: Diffuse immunoreactivity for 34βE12. |

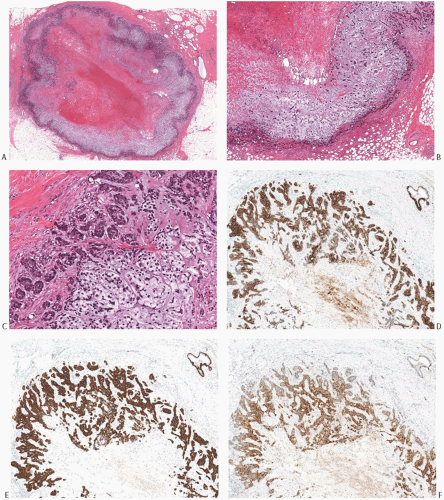

FIG. 16.22. Metaplastic carcinoma, high-grade adenosquamous type. A: This tumor has a nodular growth pattern. B: Strong immunoreactivity for 34βE12, a basal CK, highlights the carcinoma. Foci of necrosis have lighter and irregular staining. C: Bands of carcinoma in sclerotic stroma. D: Staining for CK7 highlights the glandular component. E: The myoepithelial/squamous component shows nuclear reactivity for p63. |

In contrast to metaplastic carcinoma, a malignant tumor common in peri- and postmenopausal women, fibromatosis tends to occur in women of fertile age, but this difference is not absolute. The spindle cells of fibromatosis are myofibroblasts arranged in broad sweeping fascicles and show no cytologic atypia. Mitoses are extremely infrequent. Positive nuclear staining for β-catenin in a spindle cell lesion involving the breast is not sufficient to diagnose fibromatosis. Lacroix-Triki et al.64 documented nuclear staining for β-catenin in 94% of benign and 57% of malignant PTs, and in 23% of metaplastic carcinomas. The same authors found no mutations of the β-catenin gene in a subset of PTs and metaplastic carcinomas showing nuclear positivity for β-catenin.64 Nuclear β-catenin staining occurring in a metaplastic breast carcinoma is regarded as a manifestation of EMT.

Metaplastic carcinoma with spindle cell morphology must be considered in the differential diagnosis of any spindle lesion encountered in a needle core biopsy specimen, including proliferations with bland cytology. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) should always be employed in an effort to detect CK expression or p63 reactivity (see Immunohistochemistry section in this chapter). Even if no keratin positivity is documented in the core biopsy material, the final report of a spindle cell lesion should mention metaplastic spindle cell carcinoma in the differential diagnosis and indicate the need to evaluate the excised tumor.

Heterologous Metaplastic Carcinoma

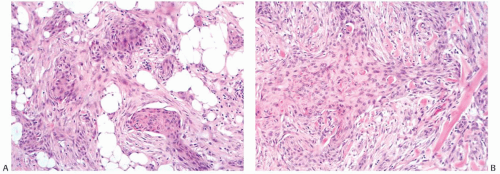

Heterologous metaplastic carcinoma is characterized by differentiation into elements with a mesenchymal phenotype such as cartilage or bone (Fig. 16.4). Zones of spindle cell metaplasia usually intervene between the adenocarcinomatous and heterologous elements. Metaplastic carcinomas with heterologous rhabdomyosarcomatous, liposarcomatous, and angiosarcomatous metaplasia can also occur, but they are much less frequent. One case of metaplastic carcinoma with neuroectodermal metaplasia has been reported.65 In general, carcinomas with heterologous metaplasia tend to retain an epithelial component, which may be glandular and/ or squamous (Figs. 16.23 and 16.24). In a few cases, the lesion is composed largely of undifferentiated spindle cell elements with scant heterologous components and tends to resemble

a high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma52 (Fig. 16.25). Myxoid change, a common feature of these undifferentiated elements, may also be found in transitional zones between adenocarcinoma and chondroid metaplasia. Highly cellular areas resembling fibrosarcoma were described in nearly half of the cases in one series.6

a high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma52 (Fig. 16.25). Myxoid change, a common feature of these undifferentiated elements, may also be found in transitional zones between adenocarcinoma and chondroid metaplasia. Highly cellular areas resembling fibrosarcoma were described in nearly half of the cases in one series.6

Metaplastic Carcinoma with Matrix Production (with or without Cartilaginous and/or Osteoid Matrix)

Matrix-producing carcinoma is a variant of heterologous metaplastic carcinoma composed of “overt carcinoma with direct transition to a cartilaginous and/or osseous stromal matrix without an intervening spindle cell zone or osteoclastic cells”66 (Fig. 16.26). Well-formed cartilage and bone are absent. The majority of these tumors are circumscribed or nodular, but occasional lesions have infiltrative borders. Sonographic examination in one case revealed a wellcircumscribed nodular hypoechoic tumor that exhibited marginal enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography.67

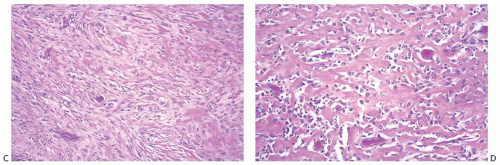

FIG. 16.25. Metaplastic carcinoma, spindle cell with chondroid differentiation. A: Focal chondroid differentiation in a spindle cell carcinoma. B: Magnified view of a well-developed cartilaginous focus. C: The spindle cell areas were immunoreactive for CK 34βE12. |

Microscopically, the carcinomatous element in matrix-producing tumors is usually moderately to poorly differentiated

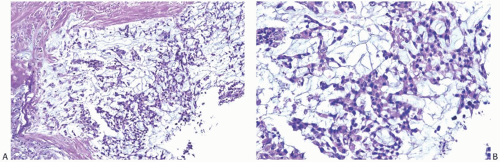

adenocarcinoma, often with small cell features and infrequent foci of squamous or apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 16.27). In some tumors, the mucoid matrix may superficially resemble mucinous carcinoma, especially if only limited material is available for review (Figs. 16.28 and 16.29). Mucin positivity is demonstrated in the stroma, but chondroid forming cells do not contain intracellular mucin. Areas that resemble pleomorphic adenoma can be found in some tumors.68 The chondroid matrix has histochemical properties of a sulfated acid mucopolysaccharide consistent with chondroitin sulfate. The carcinoma cells stain positively for CK, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and S-100 in adenocarcinoma areas (Fig. 16.30).

adenocarcinoma, often with small cell features and infrequent foci of squamous or apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 16.27). In some tumors, the mucoid matrix may superficially resemble mucinous carcinoma, especially if only limited material is available for review (Figs. 16.28 and 16.29). Mucin positivity is demonstrated in the stroma, but chondroid forming cells do not contain intracellular mucin. Areas that resemble pleomorphic adenoma can be found in some tumors.68 The chondroid matrix has histochemical properties of a sulfated acid mucopolysaccharide consistent with chondroitin sulfate. The carcinoma cells stain positively for CK, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and S-100 in adenocarcinoma areas (Fig. 16.30).

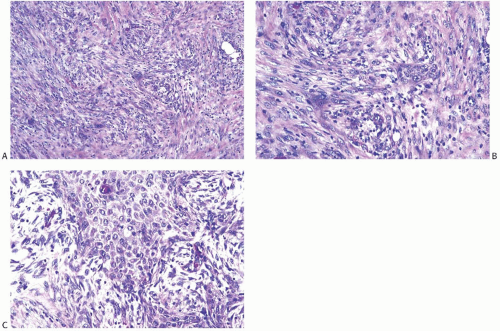

FIG. 16.26. Metaplastic carcinoma, matrix-producing type. A: A small focus of matrix formation emerging from poorly differentiated small cell carcinoma. B: Metastatic matrix-producing carcinoma in an ALN from the tumor shown in (A). C: Magnified view of matrix-producing carcinoma. |

In published series,38,42,66,69,70,71,72,73 the patient mean age was 56 years, ranging from 5038,42,70 to 58 years.66 The mean tumor size ranged between 2.442 and 3.9 cm.69 The smallest tumor spanned 0.7 cm42 and the largest 11.0 cm.70

Downs-Kelly et al.38 studied 32 cases of matrix-producing metaplastic carcinomas. Chondromyxoid or chondroid matrix constituted more than 40% of the tumor mass in 9 (28%) cases, between 10% and 40% of the tumor in another 9 (28%), and

comprised less than 10% of the tumor in the remaining 14/32 (44%) cases. The neoplastic cells in the matrix had low-grade morphology in 23/34 (72%) cases. One tumor also contained focal (less than 5%) osseous matrix. The tumor was minimally invasive in 50% of the cases, multinodular with pushing border in 33% and had a peripheral infiltrative pattern in 17% of the cases. The invasive NOS component associated with the carcinomas had high-grade morphology in 30/32 (94%) tumors, and central necrosis was present in 19/32 (59%). Lymphovascular invasion has been detected in up to 25% of tumors.38

comprised less than 10% of the tumor in the remaining 14/32 (44%) cases. The neoplastic cells in the matrix had low-grade morphology in 23/34 (72%) cases. One tumor also contained focal (less than 5%) osseous matrix. The tumor was minimally invasive in 50% of the cases, multinodular with pushing border in 33% and had a peripheral infiltrative pattern in 17% of the cases. The invasive NOS component associated with the carcinomas had high-grade morphology in 30/32 (94%) tumors, and central necrosis was present in 19/32 (59%). Lymphovascular invasion has been detected in up to 25% of tumors.38

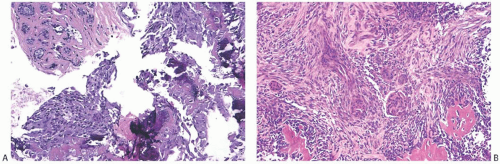

FIG. 16.28. Matrix-producing carcinoma with mucinous appearance. A,B: These areas lack a distinct rim of carcinoma cells and resemble invasive mucinous carcinoma. |

Lymph node metastases were present in 5.8%,66 22%,38 23%,69 and 45.5%42 of cases (Figs. 16.26 and 16.31). The morphology of the lymph node metastases was chondroid in 60% of cases in one series.42 In another study,38 the lymph node metastases were purely carcinomatous in four of six cases available for review, consisted of matrix-producing carcinoma in one case and of carcinoma with focal (1 mm) chondromyxoid matrix in the remaining case. Distant metastases usually have the same matrix-producing pattern as the primary tumor.

In the series of 21 chondroid metaplastic carcinomas reported by Gwin et al.,42 38% of the lesions also had foci of squamous differentiation. All tumors were estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), androgen receptor (AR), and HER2 negative, and 88% overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Positive staining for S-100, p63, and calponin was also identified. A similar pattern of immunoreactivity has been reported by Shui et al.,70 who also observed low positivity for ER (one case) and PR (three cases).

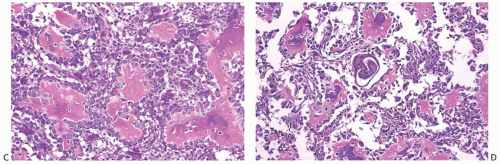

FIG. 16.29. Matrix-producing carcinoma, chest wall recurrence. A,B: The matrix-producing pattern resembles mucinous carcinoma. |

FIG. 16.30. Matrix-producing carcinoma immunoreactivity. A: Nuclear reactivity for S-100 protein is shown in adenocarcinoma (right) and matrix-producing carcinoma (left). Cytoplasmic reactivity is stronger in the adenocarcinoma area. B: Immunoreactivity for CK AE1:3 is limited to adenocarcinoma (left) and a normal lobule (center). |

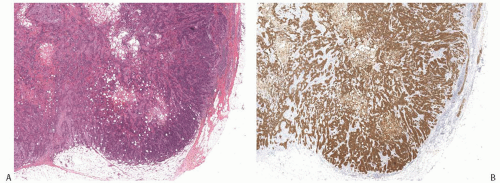

FIG. 16.31. Matrix-producing carcinoma, lymph node metastasis. A: Matrix-producing metaplastic carcinoma metastatic in a lymph node. B: A CK 34βE12 staining highlights the metastasis. C: The primary matrix-producing metaplastic carcinoma that gave rise to the metastasis depicted in (A) and (B). |

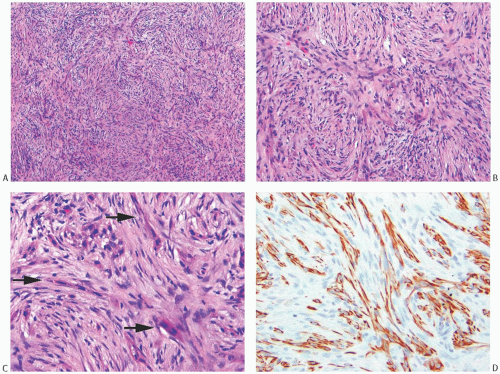

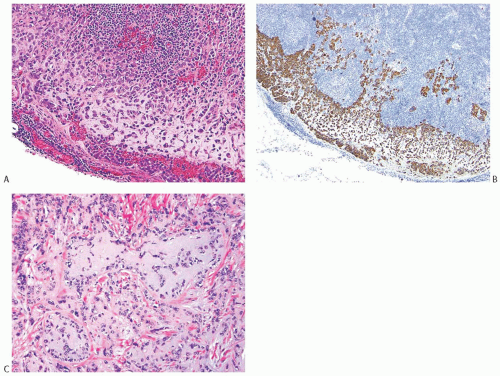

Tsuda et al.7,8 described carcinomas with central acellular necrosis/fibrosis occupying at least 30% of the tumor mass (Fig. 16.32) that are characterized by myoepithelial differentiation and a propensity to develop lung and brain metastases. Tumors with similar morphology have also been reported by other authors, sometimes under different designations. In these carcinomas, myxoid matrix is sometimes present at the interface between the central area of acellular necrosis/fibrosis and the peripheral hypercellular rim of high-grade carcinoma, raising the differential diagnosis

with metaplastic carcinoma. There is debate on the classification of these carcinomas, as they have overtly epithelial morphology and only focal myxoid matrix. However, immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated some similarities between these tumors and matrix-producing metaplastic carcinomas, as both display the basal immunoprofile and frequently have myoepithelial differentiation74 (Fig. 16.32).

with metaplastic carcinoma. There is debate on the classification of these carcinomas, as they have overtly epithelial morphology and only focal myxoid matrix. However, immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated some similarities between these tumors and matrix-producing metaplastic carcinomas, as both display the basal immunoprofile and frequently have myoepithelial differentiation74 (Fig. 16.32).

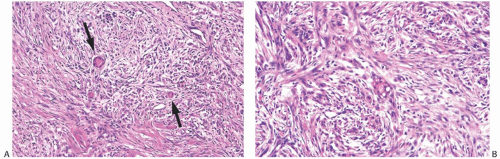

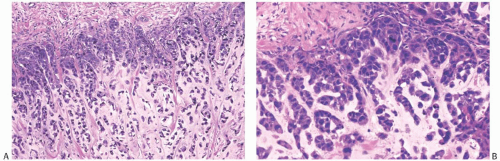

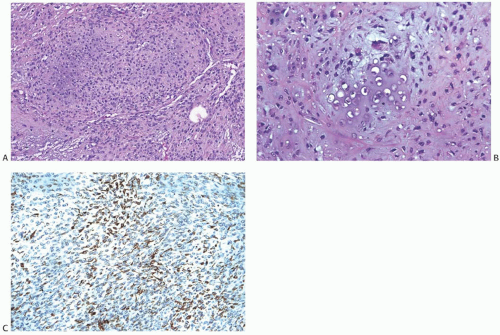

FIG. 16.32. Carcinoma with large central acellular zone of necrosis/fibrosis. A: The tumor forms a discrete nodule with a characteristic concentric arrangement. In this case, the necrotic/fibrotic center appears hemorrhagic because of a prior biopsy. This area represents more than a third of the tumor mass. It is surrounded by a band of gray hypocellular matrix, rimmed by a hypercellular area. B: Magnified view of the matrix-rich tissue band around the area of central necrosis/fibrosis. C: The matrix is relatively hypocellular compared with the hypercellular rim of basaloid cells at the periphery of the tumor. D: The tumor cells display strong immunoreactivity for CK 34βE12. E: Immunoreactivity for CK14. F: Immunoreactivity for S-100. There was no reactivity for p63 in this tumor. |

DCIS associated with matrix-producing metaplastic carcinoma was identified in 28%38 and 43%42 of cases in two series. Gwin et al.42 specified that the DCIS was solid, cribriform, micropapillary, or comedo type, with intermediate or high nuclear grade. The DCIS rarely has areas of matrix formation. In one series,66 DCIS was identified in 7/26 cases and was matrix producing in 2 cases. Some cases of matrixproducing metaplastic carcinomas arise in association with microglandular adenosis.70,75,76 One study42 found no microcalcifications in DCIS and in the invasive component.

Metaplastic Carcinomas with Multinucleated Giant Cells Resembling Osteoclasts

These tumors often exhibit osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia,6,18,77 but multinucleated giant cells can also occur admixed with malignant spindle cells without chondroosseous metaplasia17 (Fig. 16.33). Metaplastic carcinomas with this morphology usually do not display the degree of stromal hemorrhage and prominent adenocarcinoma typically found in carcinomas with osteoclast-like cells described in Chapter 23. Osteoclast-like giant cells may be found clustered around thin-walled vascular spaces in the primary tumor and in metastatic foci involving axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) and distant sites. Lee et al.78 studied the p53 gene in a metaplastic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells. They found strong p53 reactivity and the same p53 gene point mutation in the intraductal carcinoma and in the sarcomatoid component, but not in the osteoclastlike giant cells. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that the carcinomatous and sarcomatoid elements arose from a common progenitor cell, and that the giant cells were reactive constituents. DCIS is frequently found near these tumors.

Metastases of Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma

Metastases derived from a metaplastic carcinoma can consist entirely of adenocarcinoma, entirely of metaplastic elements, or they may contain a mixture of both components (Figs. 16.26, 16.31, 16.34, and 16.35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree