Mammary Carcinomas with Endocrine Features

EDI BROGI

Some mammary carcinomas are able to synthesize hormones not considered to be normal products of the breast. The capacity to produce ectopic hormones may be considered endocrine or biochemical metaplasia. Such tumors have been found to contain peptide hormones including human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG),1 calcitonin,2 adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH),3 parathormone,4 as well as norepinephrine.5 These substances are detectable not only by biochemical analysis, but also by immunohistochemical study of the tumor tissue, and rarely do they produce clinical symptoms.

In a few unusual instances, the microscopic growth pattern of the carcinoma simulates the structure of nonmammary neoplasms that commonly contain the ectopic substance, resulting in coincidence of the biochemical and structural phenotypes. A striking example of this phenomenon is mammary carcinoma with choriocarcinomatous differentiation.1,6 Most breast carcinomas with endocrine features have neuroendocrine (NE) morphology or differentiation.

CARCINOMAS WITH NEUROENDOCRINE DIFFERENTIATION

Breast carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation (NE-BCs) are relatively uncommon. In this chapter, we describe NE-BCs of low- to intermediate-grade morphology. High-grade NE carcinomas/small cell carcinomas are discussed in Chapter 21.

In 1977, Cubilla and Woodruff7 described breast carcinomas rich in argyrophilic granules and morphologically similar to carcinoid tumors that occur in other organs. The authors could not demonstrate argyrophilic granules in normal breast epithelium, but nonetheless suggested that these tumors were NE mammary neoplasms derived from argyrophilic cells of neural crest origin, presumed to have migrated to mammary ducts. This hypothesis has not found supportive evidence. Although it might be argued that NE-BCs could be referred to as “primary carcinoid tumors of the breast,” this terminology is inappropriate, as these tumors are true carcinomas.

The origin of NE-BCs and their relationship with invasive ductal carcinomas of the usual type have been extensively investigated. Albeit limited, recent evidence suggests that NE-BCs constitute a genetically distinct group of breast carcinomas, and that they are unrelated to invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type (see section on genetics and molecular studies).

At present, positivity for one NE marker, either chromogranin A or synaptophysin, in at least 50% of the tumor cells is required for the diagnosis of invasive NE-BC. Breast carcinomas with NE morphology and positive reactivity for chromogranin and/or synaptophysin in less than 50% of the cells are referred to as breast carcinomas with NE morphology. NE morphology sometimes can be subtle, adding to the difficulties in achieving reproducible diagnosis.

Clinical Presentation

Incidence, Age, and Ethnicity

It is estimated that NE-BCs represent about 1% to 2% of all breast carcinomas, but definitive information on the incidence of this type of tumors is lacking.

The mean age at diagnosis of NE-BC was 54,8 47.8,9 and 63 years10 in three recent series. Most studies and case reports document the highest incidence in postmenopausal patients older than 60 years.11,12,13 Few cases have been described in young women, many of them in Asian countries.7,14,15 In one series from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center,10 80% of patients were Caucasian, 11% Hispanic, 7% African American, 1% Asian, and 1% of unknown ethnicity. A patient developed an NE-BC during pregnancy.16 NE-BCs can also occur in men.10,13,17

Clinical Findings

An NE-BC usually presents as a palpable mass8 in the central and retroareolar region of the breast or in the upper outer quadrant. Nipple discharge, often bloody, is a relatively common presenting symptom. Kawasaki et al.9 reported that 24/89 (27%) patients with bloody nipple discharge had a

carcinoma with NE differentiation, including eight invasive carcinomas. Bilateral synchronous tumors have also been reported.5,14 At present, there are no documented reports of NE-BCs occurring in patients with a known (neuro)endocrine syndrome.

carcinoma with NE differentiation, including eight invasive carcinomas. Bilateral synchronous tumors have also been reported.5,14 At present, there are no documented reports of NE-BCs occurring in patients with a known (neuro)endocrine syndrome.

Radiology

Gunhan-Bilgen et al.18 evaluated the radiologic features of five NE-BCs. One of the tumors was detected at mammographic screening, and the other four presented as palpable masses, which were soft and mobile in two patients and firm and immobile in the other two. In all five cases, mammographic examination detected a high-density mass with no calcifications. The tumor mass was round in four of five cases and irregular in one. The margins were spiculated in two cases, and indistinct, microlobulated, and partially lobulated to partially obscured in one case each. At ultrasound examination, four of five masses had heterogeneous hypoechoic signal with mild posterior acoustic enhancement. The masses were round or irregular, and the margins appeared irregular, microlobulated, or well circumscribed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of one tumor revealed a round mass with irregular margins and homogeneous contrast enhancement. After gadolinium-injection, the tumor exhibited early enhancement, followed by signal plateau, consistent with a malignant neoplasm. Just as NE epithelial neoplasms occurring at other sites, NE-BCs may have a positive signal when examined by indium111-octreotide radionuclide scanning.19

Gross Pathology

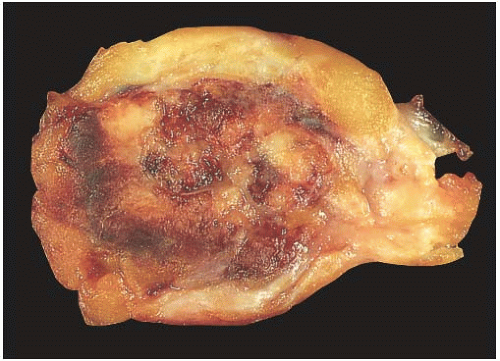

NE-BCs and breast carcinomas with NE features usually are grossly circumscribed and somewhat hemorrhagic (Fig. 20.1), with a white gray to tan cut surface. They often have a soft, delicate, even friable consistency. Rarely multiple foci of carcinoma were described in the breast.

FIG. 20.1. Carcinoma with endocrine features, gross appearance. The carcinoma forms a circumscribed mass with a hemorrhagic cut surface. |

The invasive tumors generally measure 1 to 5 cm in diameter, with most spanning between 1.5 and 3.0 cm. In one recent series,8 the mean and the median tumor size were 2.7 and 2.2 cm, respectively, with a range from 0.8 to 13.5 cm.

Microscopic Pathology

Invasive Carcinomas with NE Differentiation and/or Features

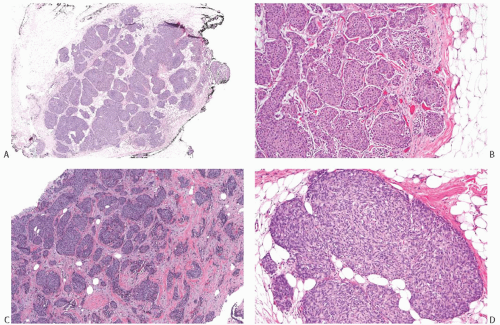

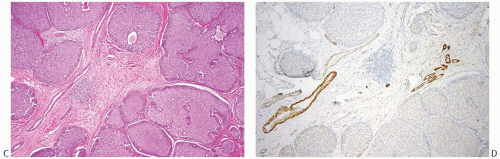

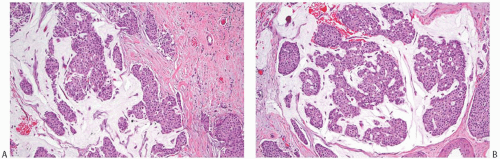

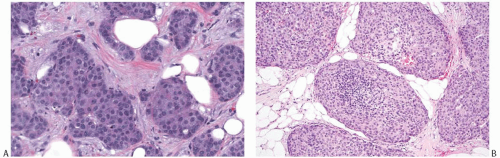

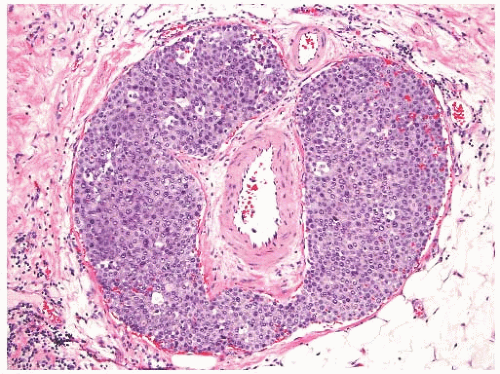

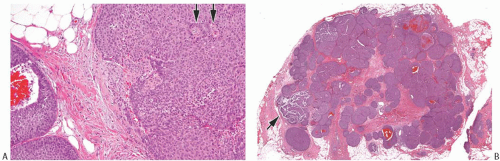

NE-BCs and breast carcinomas with NE features commonly have a nested (Fig. 20.2) and/or solid-papillary (Fig. 20.3) growth pattern. The tumor nests are with a smooth or irregular outline and vary in size, ranging from large and cohesive to small and scattered. The nests are often distributed haphazardly like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Tumor rosettes and trabecular arrangement are commonly present, at least focally. Focal infiltration into the adipose tissue is usually evident. The papillae of papillary NE-BC are often large, typically solid, and have inconspicuous and delicate fibrovascular cores containing thin capillaries (Fig. 20.3). The nested and solid-papillary invasive variant of NE-BC can be difficult to recognize, as it can closely resemble ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)13,20,21 (Figs. 20.2 and 20.3). Compared with the latter, invasive papillary NE-BC consists of nests and solid papillae of varying size and shape that are devoid of a myoepithelial layer (Fig. 20.3). In a series of solid and papillary carcinomas reported by Maluf and Koerner,22 no smooth muscle actin (SMA) reactivity was present in the fibrovascular cores and at the periphery of 11/12 tumors, raising the possibility that most of the tumors were invasive. Righi et al.12 studied a series of 89 NE-BCs. After excluding 11 “small cell” carcinomas, 35/78 (45%) cases had solid and cohesive architecture, 20/78 (25%) were solid and papillary, 13/78 (17%) cellular mucinous (Fig. 20.4), and 10/78 (13%) alveolar. The NE-BCs reported by Tang et al.11 were papillary in 80% of cases; nested in 64%; and cellular mucinous, trabecular, or micropapillary in 3% of cases each. A glandular pattern of no special type was present in 18% of cases, and mixed architectural patterns were observed in 59% of tumors. Mucinous differentiation is not uncommon in NE-BC, often in the form of type B/cellular mucinous carcinoma or of mucinous carcinoma with type A and B morphology (see also Chapter 18). Any papillary epithelial proliferation with associated mucin should be regarded as at least atypical or suspicious for carcinoma and worked up accordingly. The tumor papillae have delicate filiform fibrovascular cores that are often apparent as cross sections of capillaries. Some papillae consist of abundant hyalinized and amorphous, nearly acellular stroma.

The tumor cells have relatively abundant cytoplasm (Fig. 20.5), which is often eosinophilic or granular, but can occasionally have a gray-blue hue because of intracytoplasmic mucin, or appear clear and almost vacuolated. The neoplastic cells are polygonal or plasmacytoid, but sometimes acquire signet cell morphology because of abundant intracytoplasmic mucin. Other shapes include ovoid, round, or spindled.

The nuclear features of NE-BC are also quite variable. Most often the nuclei are round to ovoid, located at the base or at one pole of the cell. They have smooth, fine, or “saltand-pepper” chromatin. Nucleoli are usually absent or inconspicuous. The differential diagnosis of small cell carcinoma should be considered whenever an NE-BC has high-grade, basaloid nuclei and a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio.

FIG. 20.3. Invasive carcinoma with neuroendocrine features, solid and papillary pattern. A: The solid and papillary invasive carcinoma on the right has an irregular edge. Rare delicate fibrovascular cores are noted (arrows). Two ducts involved by DCIS are present on the left. B: Whole-slide magnification of a mass-forming solid and papillary carcinoma. Most of the tumor has solid and papillary growth, but focal mucin production is evident (arrow). C: Large solid and papillary nodules of carcinoma with NE morphology in the tumor shown in (B). D: The section stained for calponin reveals myoepithelium in normal ducts. The absence of staining in and around the tumor is not definitive evidence of invasion because myoepithelium may be lost in DCIS. |

Stromal desmoplasia tends to be rare, but a slight increase of stromal myofibroblasts admixed with inflammatory cells is a frequent finding around invasive tumor nests, at least focally. Focal peritumoral retraction and absence of basement membrane are easily detected. In some tumors, the stroma is

hyalinized, hypocellular, and nearly sclerotic. The tumors show prominent vascularity, with easily identifiable sinusoids and small feeding vessels. Blood lakes, extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin deposits, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are also frequently encountered. In one series,11 lymphovascular invasion was present in 38% of 74 NE-BCs (Fig. 20.6).

hyalinized, hypocellular, and nearly sclerotic. The tumors show prominent vascularity, with easily identifiable sinusoids and small feeding vessels. Blood lakes, extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin deposits, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are also frequently encountered. In one series,11 lymphovascular invasion was present in 38% of 74 NE-BCs (Fig. 20.6).

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

DCIS with NE features can occur alone or in association with invasive NE carcinoma. The largest series consisting of 34 cases of NE-DCIS, including 14/34 (41%) pure DCIS, was reported by Tsang and Chan.23 Kawasaki et al.24 identified NE differentiation in 20/294 (6.8%) consecutive cases of DCIS. Bloody nipple discharge is a common symptom.23 It constituted the presenting sign in 13/20 (65%) cases in one series,24 whereas only one NE-DCIS (6%) manifested as a mass lesion. Compared with non-NE-DCIS, DCIS with NE differentiation is rarely detected by mammographic screening. In a study by Kawasaki et al.,24 the rate of mammographically detected NE-DCIS was 11% versus 54% for non-NE-DCIS (p < 0.01). Cases of bilateral NE-DCIS have been reported.23,25,26

Akin to NE-BCs, DCIS with NE features is also more common in postmenopausal women,23 and often involves the central retroareolar region or the upper outer quadrant of the breast. It usually forms a circumscribed, tan-pink mass, with soft and friable consistency.

Morphologically NE-DCIS is often solid and/or papillary, with expansive growth. At least one case of solid papillary DCIS with SMA-positive myoepithelium lining the fibrovascular cores and the periphery of the tumor was part of the series by Maluf and Koerner.22 The solid epithelial proliferation contains scattered small inconspicuous acini lined by polarized cells. A palisading “picket fence” arrangement along the fibrovascular cores is common (Fig. 20.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree