Chapter 5 The Lower Extremity

The hamstring origin from the ischial tuberosity is often avulsed before skeletal maturity.

Pressure ulcers may develop over ischial tuberosities from unrelieved pressure.

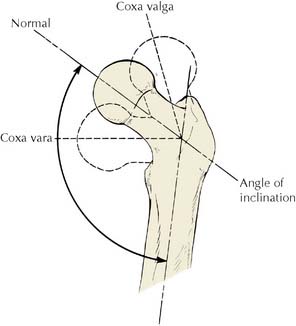

A common fracture in elderly women with osteoporosis is the fracture of the femoral neck. Femoral neck fractures in younger individuals are usually due to high-energy trauma but can be stress fractures from unaccustomed strenuous activity (e.g., in military recruits). The angle of inclination is decreased in coxa vara (e.g., femoral neck fracture) and increased in coxa valga (e.g., developmental dysplasia of the hip) (Figure 5-2). Both may congenital or acquired conditions.

(From Chung, S M K: Hip Disorders in Infants and Children. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1981, p 85.)

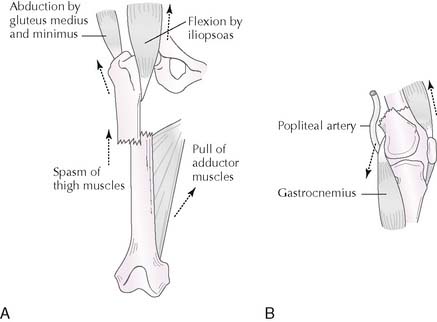

Fracture of the femoral shaft causes substantial shortening of the femur from contraction of the powerful longitudinally oriented muscles (Figure 5-3, A).

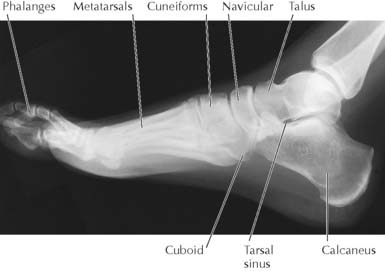

Falling or jumping from a height may fracture the body of the talus and calcaneus. Violent dorsiflexion of the ankle joint (e.g., in motor vehicle accidents) may fracture the neck of the talus (Figure 5-5), which can interrupt the blood supply and lead to avascular necrosis of the body of the talus.

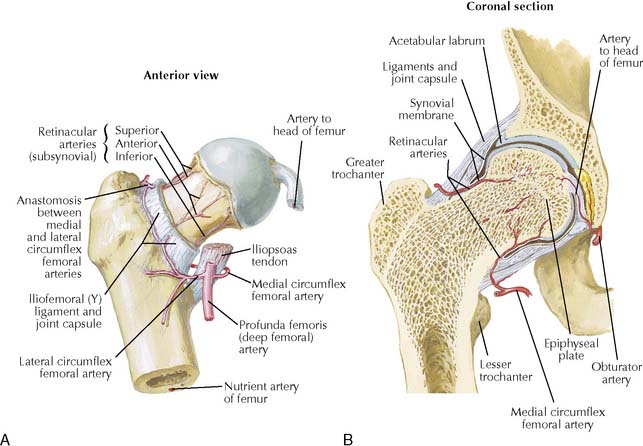

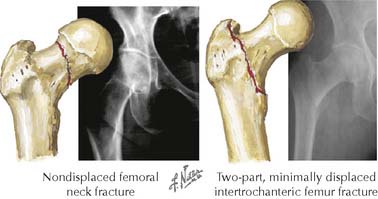

The hip frequently fractures at the femoral neck adjacent to the femoral head (subcapital fracture) and less frequently between the trochanters (pertrochanteric/intertrochanteric fracture). Intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck may interrupt the blood supply to the femoral head, resulting in avascular necrosis (Figures 5-6 and 5-7). Fractures are more common in elderly females than males because the incidence of osteoporosis is increased after menopause.

5-7 Fractures of proximal femur. Intracapsular fracture of femoral neck, especially if displaced, may disrupt blood supply to femoral head via retinacular branches of medial femoral circumflex artery and cause avascular necrosis. Intertrochanteric fracture is extracapsular and does not compromise blood supply to femoral head (see Figure 5-6).

(From Greene, W B: Netter’s Orthopaedics. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2006, Figure 17-21.)

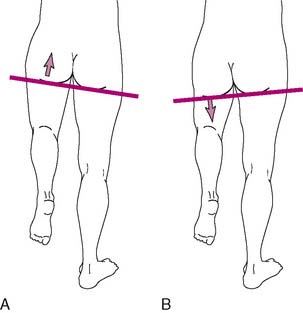

A positive Trendelenburg sign often indicates paralyzed or weak gluteus medius and minimus muscles on the weight-bearing side that cause inability to abduct the hip (i.e., keep the pelvis level) (Figure 5-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree