Chapter 4 The Pelvis and the Perineum

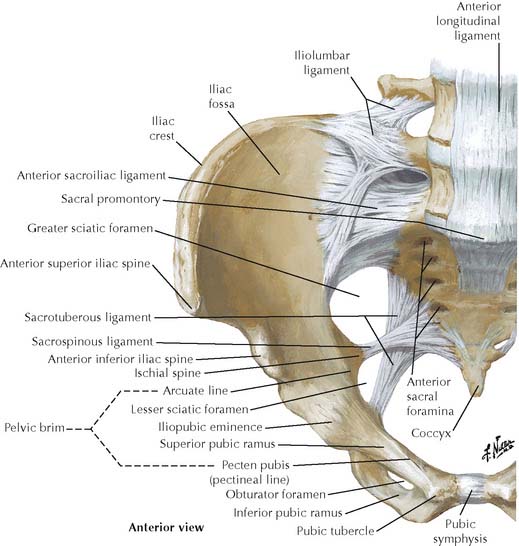

Traumatic pelvic fractures often occur in two places with pelvic organ injury and hemorrhage.

Avulsion fractures occur at muscle attachments in skeletally immature patients.

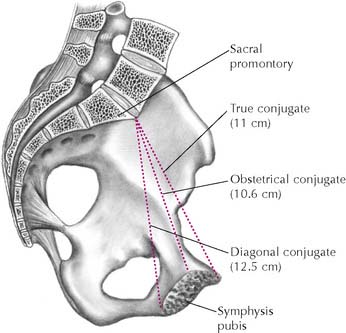

TABLE 4-1 Pelvic Measurements of Obstetrical Significance

| Measurement | Distance | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic Inlet | ||

| True conjugate diameter | AP distance between sacral promontory and upper border of pubic symphysis | |

| Diagonal conjugate diameter | AP distance between sacral promontory and lower border of pubic symphysis | Measured during vaginal exam |

| Transverse diameter | Greatest distance between right and left arcuate lines | |

| Oblique diameter | Distance between one sacroiliac joint and contralateral iliopubic eminence | |

| Midpelvis | ||

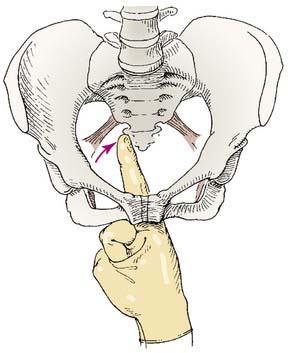

| Interspinous (midpelvic) diameter | Distance between ischial spines | Narrowest point of birth canal; estimated during vaginal exam |

| Pelvic Outlet | ||

| Anteroposterior diameter | Distance between tip of coccyx and lower border of pubic symphysis | |

| Intertuberous (transverse) diameter | Distance between medial surfaces of ischial tuberosities | Smallest diameter of pelvic outlet |

AP, anteroposterior.

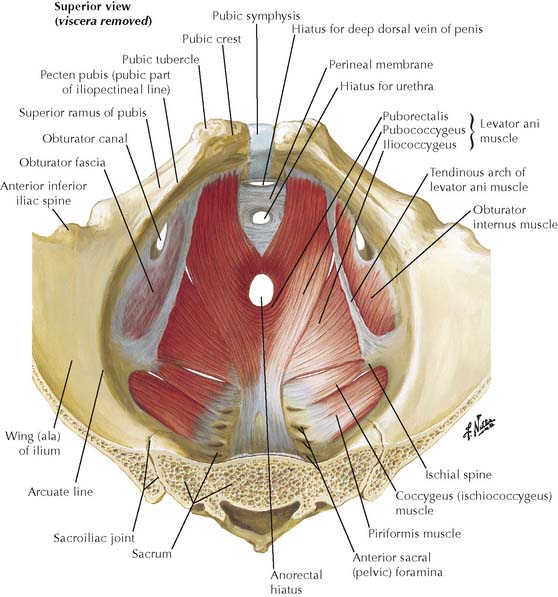

TABLE 4-2 Differences between Male and Female Bony Pelvis

| Feature | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| False pelvis | Deep | Shallow |

| Pelvic inlet | Narrow and heart-shaped | Wide and almost oval |

| Pelvic cavity | Longer, tapered, cone-shaped | Shorter, cylindrical, roomier |

| Pelvic outlet | Smaller | Larger because of eversion of ischial tuberosities and wider subpubic angle |

| Subpubic angle | <70° | >80° |

| Shape of sacrum | Longer, narrower, and more curved | Shorter, wider, and flatter |

| Anterior pelvic wall | Longer | Shorter |

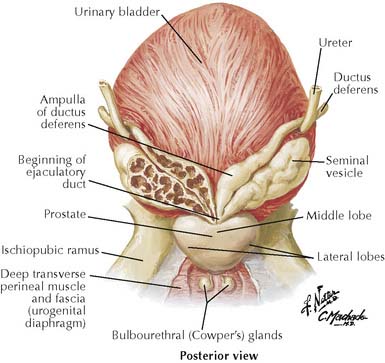

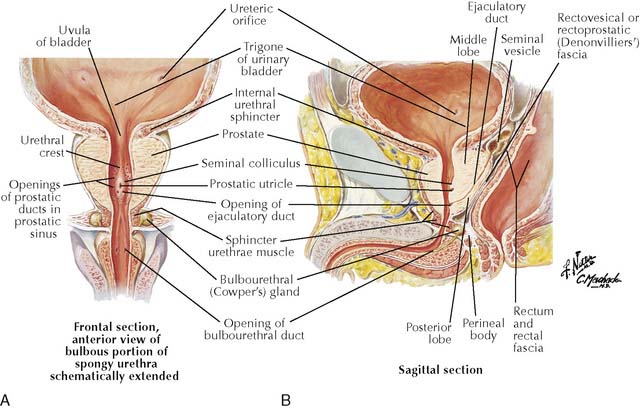

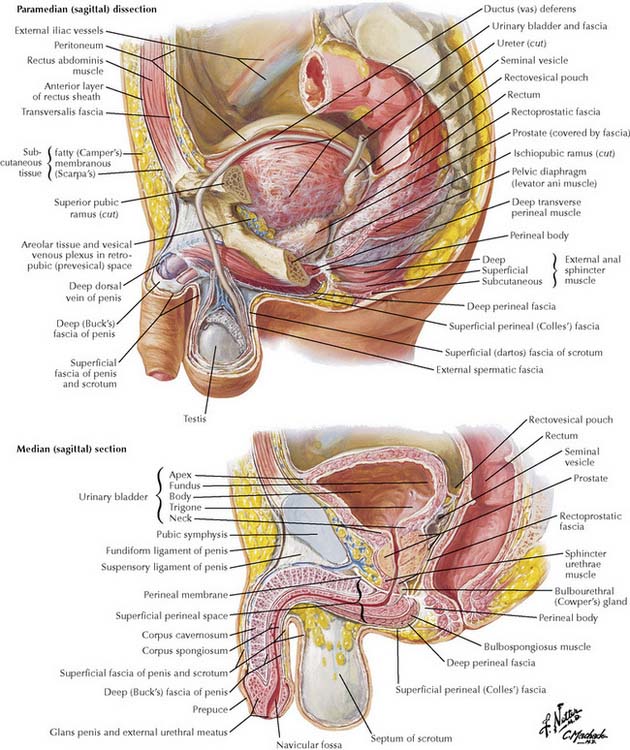

4-6 Male pelvic organs in paramedian and median sagittal sections.

(From Netter, F H: Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2006, Plate 361.)

Renal calculi (kidney stones) typically obstruct the ureter at its three sites of constriction. Most calculi are too small to be seen on plain radiographs, so an intravenous pyelogram is required (Figure 4-8).

Obstruction of the oblique course of the ureter through the bladder wall (e.g., due to detrusor muscle hypertrophy, invasion by cervical cancer) or vesicoureteral reflux due to trigonal muscle weakness may cause backup of urine. The result is hydroureter and hydronephrosis. The ureter becomes elongated and tortuous due to smooth muscle that hypertrophies to increase peristaltic force (see Figure 4-8, B).

Ulcerative colitis is the most common inflammatory disease of the bowel and is limited to the colon. It is mainly a disease of young adults that begins in the rectum and spreads proximally, involving only the mucosa and submucosa with continuous ulcerations (Figure 4-9). Islands of residual mucosa produce pseudopolyps. The patient experiences recurrent left-sided abdominal cramping with bloody mucoid diarrhea. In the most severe cases, toxic damage to parasympathetic ganglia stops bowel function, and the colon progressively swells and becomes gangrenous (toxic megacolon). Patients have an increased risk of adenocarcinoma.

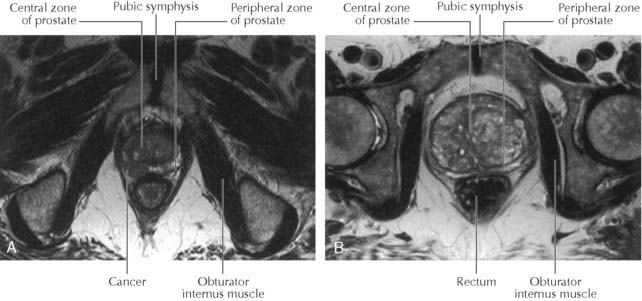

Prostate cancer usually begins in the periphery of the gland in a region that corresponds to the anatomical posterior lobe (Figure 4-13), so early stages are often asymptomatic. Later, in advanced disease, prostate cancer can occlude the prostatic urethra, causing obstruction. After age 50, primary methods of detection include an annual digital rectal examination (Figure 4-14) and blood tests for prostate-specific antigen (PSA).