Chapter 15 The Kidneys and the Urinary System

1 List the most important kidney diseases

Tubulointerstitial diseases (One percent of all people in the United States will develop renal stones during their life span.)

Tubulointerstitial diseases (One percent of all people in the United States will develop renal stones during their life span.)3 What are the principal laboratory findings in uremia?

Electrolyte abnormalities (retention of sodium, potassium, and phosphate, with secondary changes in the concentration of calcium, which is initially low but also may be high)

Electrolyte abnormalities (retention of sodium, potassium, and phosphate, with secondary changes in the concentration of calcium, which is initially low but also may be high)4 What are the common clinical features of uremia?

Clinical features of uremia may be found in essentially all major organs and include:

5 What are the features of acute nephritic syndrome?

Hematuria: It results from rupture or increased porosity of damaged glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Glomerular hematuria presents with brownish-red urine (“bouillon soup–like”). Red blood cells (RBCs) may be found in the urine sediment examined by microscopy. The sediment also contains fragmented and distorted RBCs and RBC casts.

Hematuria: It results from rupture or increased porosity of damaged glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Glomerular hematuria presents with brownish-red urine (“bouillon soup–like”). Red blood cells (RBCs) may be found in the urine sediment examined by microscopy. The sediment also contains fragmented and distorted RBCs and RBC casts. Proteinuria: It reflects the increased permeability of the GBM. The amount of protein found in urine varies from mild to severe.

Proteinuria: It reflects the increased permeability of the GBM. The amount of protein found in urine varies from mild to severe. Generalized edema: It is a complication of hypoalbuminemia. Typically it is most prominent on the face (“puffy eyes”) because of periorbital edema but may involve body cavities and internal organs. Somnolence of affected children is in part related to brain edema.

Generalized edema: It is a complication of hypoalbuminemia. Typically it is most prominent on the face (“puffy eyes”) because of periorbital edema but may involve body cavities and internal organs. Somnolence of affected children is in part related to brain edema. Low complement levels in blood: This laboratory findings reflect the consumption of complement, which is bound to immune complexes deposited in the glomeruli.

Low complement levels in blood: This laboratory findings reflect the consumption of complement, which is bound to immune complexes deposited in the glomeruli.6 List the features of nephrotic syndrome

Hyperlipidemia: It is mostly due to an increased amount of low density lipoproteins (LDLs) and lipiduria (lipid casts in urine).

Hyperlipidemia: It is mostly due to an increased amount of low density lipoproteins (LDLs) and lipiduria (lipid casts in urine).8 What are the causes of acute renal failure?

Three types of renal failure are recognized: prerenal, renal, and postrenal. See Table 15-1.

TABLE 15-1 Cause of Acute Renal Failure

| Type of Renal Failure | Pathogenesis | Clinical Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Prerenal | Decreased renal perfusion | Congestive heart failure |

| Loss of blood | Massive bleeding | |

| Renal | Glomerular disease | Acute glomerulonephritis |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | Drug reaction | |

| Vasculitis | Wegener granulomatosis | |

| Toxic tubular necrosis | Mercury poisoning | |

| Postrenal | Intratubular obstruction | Acute urate nephropathy |

| Renal–pelvic obstruction | Nephrolithiasis | |

| Ureteric obstruction | Urinary stones | |

| Bladder/urethral obstruction | Prostatic hyperplasia |

9 How does chronic renal failure develop?

Diminished renal reserve: These patients do not have clinical or laboratory signs of renal disease (BUN and Cr are normal). Additional testing will reveal that GFR is significantly reduced, and azotemia may develop during intercurrent diseases.

Diminished renal reserve: These patients do not have clinical or laboratory signs of renal disease (BUN and Cr are normal). Additional testing will reveal that GFR is significantly reduced, and azotemia may develop during intercurrent diseases. Renal insufficiency: These patients have reduced GFR (20%–50% of normal) and show signs of reduced tubular function. Laboratory findings include azotemia, anemia, and polyuria.

Renal insufficiency: These patients have reduced GFR (20%–50% of normal) and show signs of reduced tubular function. Laboratory findings include azotemia, anemia, and polyuria. Renal failure: These patients have markedly reduced GFR (<20% of normal), edema, metabolic acidosis, hypocalcemia, and multisystemic signs of uremia.

Renal failure: These patients have markedly reduced GFR (<20% of normal), edema, metabolic acidosis, hypocalcemia, and multisystemic signs of uremia.10 Define derangements of urine volume

Anuria: It is characterized by reduced urine output (<100mL urine per day), reflecting renal injury.

Anuria: It is characterized by reduced urine output (<100mL urine per day), reflecting renal injury. Oliguria: It is defined as reduced urine output below 400mL/day. Such urinary volume is insufficient to excrete the daily osmolar load. It occurs often in the clinical setting and may be caused by prerenal, renal, or postrenal renal failure.

Oliguria: It is defined as reduced urine output below 400mL/day. Such urinary volume is insufficient to excrete the daily osmolar load. It occurs often in the clinical setting and may be caused by prerenal, renal, or postrenal renal failure. Polyuria: It is defined as increased volume of urine (>3 L of urine per day). It may result from excessive fluid intake (e.g., beer), osmotic diuresis (e.g., diabetes mellitus), inappropriate fluid loss (e.g., diabetes insipidus), or impaired tubular concentration (e.g., tubular necrosis). Polyuria is typically found during the recovery phase of renal tubular necrosis. (Note: Regenerating renal tubules cannot concentrate urine.)

Polyuria: It is defined as increased volume of urine (>3 L of urine per day). It may result from excessive fluid intake (e.g., beer), osmotic diuresis (e.g., diabetes mellitus), inappropriate fluid loss (e.g., diabetes insipidus), or impaired tubular concentration (e.g., tubular necrosis). Polyuria is typically found during the recovery phase of renal tubular necrosis. (Note: Regenerating renal tubules cannot concentrate urine.)DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

15 What are the differences between autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive kidney disease?

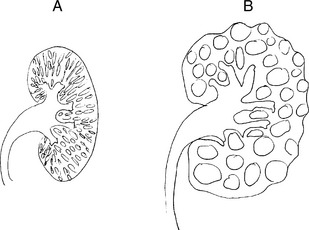

Comparisons of autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease are illustrated in Fig. 15-1 and listed in Table 15-2.

TABLE 15-2 Autosomal Dominant and Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (PCKD)

| Feature | Autosomal Dominant PCKD | Autosomal Recessive PCKD |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Common (1:800) | Rare (1:15,000) |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal recessive |

| Gene | Polycystin genes (PKD1 = 85%) | Fibrocystin, PKHD1 |

| Bilateral | Yes | Yes |

| Gross appearance | Large cystic kidneys (>1000g) | Spongelike symmetrically enlarged (100–200g) |

| Cysts | Large (from any tubule) | Small (collecting duct derived) |

| Symptoms | Infancy, childhood | Adulthood (>35 years) |

| Associated anomalies | Polycystic liver disease (20%) Berry aneurysms of cerebral arteries | Small bile duct cysts, liver fibrosis |

GLOMERULAR DISEASES

16 What is the difference between primary and secondary glomerular diseases?

Primary glomerular diseases are, for example:

Secondary glomerular diseases occur in the course of systemic diseases such as:

Key Points: Glomerular Diseases

20 Describe two forms of antibody-associated forms of glomerular injury

Antibodies to endogenous antigens of the GBM: This mechanism accounts for the renal injury in Goodpasture syndrome, a disease caused by antibodies to collagen type IV.

Antibodies to endogenous antigens of the GBM: This mechanism accounts for the renal injury in Goodpasture syndrome, a disease caused by antibodies to collagen type IV. Antibodies to nonglomerular antigens: Antigen–antibody complexes found in the glomeruli may result from two pathogenetic mechanisms: in situ formation or intraglomerular deposition of circulating immune complexes.

Antibodies to nonglomerular antigens: Antigen–antibody complexes found in the glomeruli may result from two pathogenetic mechanisms: in situ formation or intraglomerular deposition of circulating immune complexes. In situ immune complex formation results from the binding of circulating antibodies and the “implanted” antigen fixed to the basement membrane of the glomerulus. This mechanism accounts for the formation of glomerular lesions in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. It is assumed that the streptococcal antigens are implanted into the GBM during the infection, and when the antibodies are formed, they reach the implanted antigens in the glomeruli, thus forming immune complexes.

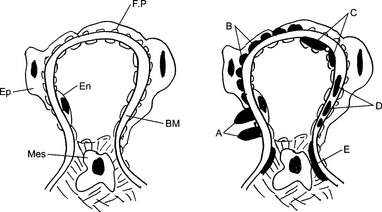

In situ immune complex formation results from the binding of circulating antibodies and the “implanted” antigen fixed to the basement membrane of the glomerulus. This mechanism accounts for the formation of glomerular lesions in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. It is assumed that the streptococcal antigens are implanted into the GBM during the infection, and when the antibodies are formed, they reach the implanted antigens in the glomeruli, thus forming immune complexes. Circulating immune complexes are antigen–antibody complexes formed from soluble antigens and corresponding antibodies in the circulating blood. The bloodstream carries these immune complexes to the glomeruli, where the blood is normally filtered. Because the preformed immune complexes represent large protein aggregates that cannot pass through the GBM, they are “caught” on the subepithelial, subendothelial side of the GBM or the lamina rara or densa of the GBM. This type of immune complex deposition typically occurs in SLE.

Circulating immune complexes are antigen–antibody complexes formed from soluble antigens and corresponding antibodies in the circulating blood. The bloodstream carries these immune complexes to the glomeruli, where the blood is normally filtered. Because the preformed immune complexes represent large protein aggregates that cannot pass through the GBM, they are “caught” on the subepithelial, subendothelial side of the GBM or the lamina rara or densa of the GBM. This type of immune complex deposition typically occurs in SLE.21 What pattern of staining of glomeruli is seen by immunofluorescence microscopy in anti-GBM nephritis?

22 What pattern of staining of glomeruli is seen by immunofluorescence microscopy in circulating immune complex nephritis?

24 In which parts of the glomeruli may the antigen–antibody complexes be seen by electron microscopy in various forms of glomerulonephritis?

Depending on their location, immune complexes are classified as follows:

Epimembranous granular deposits (e.g., membranous nephropathy or the membranous form of SLE nephritis)

Epimembranous granular deposits (e.g., membranous nephropathy or the membranous form of SLE nephritis)25 Why does the immunologic injury of the GBM cause proteinuria?

Increased permeability of the GBM without interruption of the filtration barrier: It results from complex physicochemical changes caused by the action of activated complement, enzymes, and cytokines. These changes involve the biochemical composition and electric charges of the GBM and the size of internal pores that serve as normal channels for the passage of proteins.

Increased permeability of the GBM without interruption of the filtration barrier: It results from complex physicochemical changes caused by the action of activated complement, enzymes, and cytokines. These changes involve the biochemical composition and electric charges of the GBM and the size of internal pores that serve as normal channels for the passage of proteins. Rupture of the GBM: It is usually associated with a passage of large plasma proteins (e.g., fibrinogen) and red blood cells into the urinary space. Clinically, such proteinuria is associated with hematuria. Polymerization of fibrinogen into fibrin inside the urinary space of the glomeruli can be recognized as fibrinoid necrosis of capillary loops or the early formation of crescents for which this fibrin forms the scaffold.

Rupture of the GBM: It is usually associated with a passage of large plasma proteins (e.g., fibrinogen) and red blood cells into the urinary space. Clinically, such proteinuria is associated with hematuria. Polymerization of fibrinogen into fibrin inside the urinary space of the glomeruli can be recognized as fibrinoid necrosis of capillary loops or the early formation of crescents for which this fibrin forms the scaffold.27 List the soluble mediators of inflammation that contribute to the antibody-mediated glomerular injury

Activated complement components act as chemotactic fragments and mediate the influx of neutrophils and macrophages. Complement may also increase the permeability of the GBM and cause mechanical lesions through the action of membrane attack (C5–C9 terminal complex).

Activated complement components act as chemotactic fragments and mediate the influx of neutrophils and macrophages. Complement may also increase the permeability of the GBM and cause mechanical lesions through the action of membrane attack (C5–C9 terminal complex). Cytokines (especially interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor) and chemokines participate in the recruitment of inflammatory cells and their activation and also directly contribute to the injury of the GBM. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes extracellular matrix synthesis and contributes to glomerulosclerosis in later stages of the disease.

Cytokines (especially interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor) and chemokines participate in the recruitment of inflammatory cells and their activation and also directly contribute to the injury of the GBM. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes extracellular matrix synthesis and contributes to glomerulosclerosis in later stages of the disease. In the coagulation system, fibrin and thrombin may activate platelets and other blood cells and local glomerular cells, as well as damage the GBM.

In the coagulation system, fibrin and thrombin may activate platelets and other blood cells and local glomerular cells, as well as damage the GBM.28 What are the histologic signs of chronic progression of glomerular disease?

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: This is a secondary change that occurs in the relatively unaffected glomeruli of a diseased kidney that has lost many nephrons. Normal glomeruli receive increased amounts of blood and undergo hypertrophy. The hemodynamic changes in the overburdened and enlarged glomeruli lead to segmental hyalinization of capillary loops and progressive narrowing of their lumen by sclerosis.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: This is a secondary change that occurs in the relatively unaffected glomeruli of a diseased kidney that has lost many nephrons. Normal glomeruli receive increased amounts of blood and undergo hypertrophy. The hemodynamic changes in the overburdened and enlarged glomeruli lead to segmental hyalinization of capillary loops and progressive narrowing of their lumen by sclerosis. Tubulointerstitial damage: Tubular damage results in hyalinization of tubular basement membranes and atrophy of tubular cells associated with a loss of their specific functions. The peritubular interstitial spaces increase in size and change their biochemical composition. Chronic inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes, appear in the interstitial spaces. The factors leading to tubulointerstitial injury include ischemia distal to sclerotic glomeruli, concomitant immune reactions to shared antigens, and biochemical injury by retention of metabolites or minerals (e.g., phosphate, calcium, or ammonia).

Tubulointerstitial damage: Tubular damage results in hyalinization of tubular basement membranes and atrophy of tubular cells associated with a loss of their specific functions. The peritubular interstitial spaces increase in size and change their biochemical composition. Chronic inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes, appear in the interstitial spaces. The factors leading to tubulointerstitial injury include ischemia distal to sclerotic glomeruli, concomitant immune reactions to shared antigens, and biochemical injury by retention of metabolites or minerals (e.g., phosphate, calcium, or ammonia).29 Discuss the histologic features of acute glomerulonephritis

Hypercellularity of glomeruli, which is in part due to exudation of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages) and in part due to proliferation of endogenous glomerular cells

Hypercellularity of glomeruli, which is in part due to exudation of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages) and in part due to proliferation of endogenous glomerular cells Narrowing of capillary spaces and reduced blood flow through the glomeruli (few RBCs in the glomerular capillaries)

Narrowing of capillary spaces and reduced blood flow through the glomeruli (few RBCs in the glomerular capillaries) Proteinaceous and RBC casts in the lumen of tubules (result from combined effects of glomerular proteinuria and hematuria)

Proteinaceous and RBC casts in the lumen of tubules (result from combined effects of glomerular proteinuria and hematuria)30 Describe the most common cause of postinfectious glomerulonephritis

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes) account for 90% of all glomerulonephritis cases. Glomerulonephritis typically occurs 1 to 4 weeks after a strep throat or skin infection (impetigo) caused by one of the nephritogenic strains of this microbe. Occasionally the same clinical and pathologic findings may follow staphylococcal infection and even some viral diseases, such as hepatitis B or C or hepatitis caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). See Fig. 15-3.

33 Why is the concentration of serum complement C3 low in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis?

34 What is the typical outcome and what are the possible long-term consequences of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis?

The disease has a better prognosis in children than in adults:

Children

Children Ninety percent recover within 2 or 3 months with conservative therapy aimed at maintaining sodium and water balance.

Ninety percent recover within 2 or 3 months with conservative therapy aimed at maintaining sodium and water balance. Five to eight percent have persistent glomerulonephritis, in much milder form, with abnormal urinary findings for 6 to 8 months.

Five to eight percent have persistent glomerulonephritis, in much milder form, with abnormal urinary findings for 6 to 8 months.< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree