Chapter Sixteen. The haematological system—physiology of the blood

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Blood as a tissue 209

Functions of blood 210

Constituents of blood 210

Plasma 210

Folate metabolism 214

Platelets 216

Blood as a tissue

Blood is a fluid connective tissue, which communicates between internal cells and the body surface, and between the various specialised tissues and organs. In an adult human, blood will normally comprise 6–8% of body weight; this is 5–6 litres in a man and 4–5 litres in a woman.

If a sample of blood is placed in a test-tube and prevented from clotting, the heavier cellular elements settle and the plasma rises to the top. The haematocrit, or packed cell volume fraction, essentially represents the percentage of total blood volume occupied by erythrocytes. White cells and platelets form only 1%, settle on top of the red cells and can be seen between the two main layers as a thin cream-coloured layer called the buffy coat. The haematocrit averages 45% and the plasma averages 55% of the total volume. Table 16.1 details the specific properties of blood.

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity (relative to water) | 1.026 |

| Viscosity (relative to water) | 1.5–1.75 (cells contribute equally to viscosity) |

| pH | 7.35–7.45 |

| H + concentration | 35–45 nmol/L |

Functions of blood

Blood has three general functions.

1. Transportation: Blood transports oxygen from the lungs to the cells and transports carbon dioxide from the cells to the lungs, nutrients from the gastrointestinal tract, hormones from endocrine glands and heat and waste products away from the cells.

2. Regulation: Blood is involved in the regulation of acid–base balance, body temperature and water content of cells.

3. Protection: Clotting factors in blood protect against excessive loss from the cardiovascular system. White blood cells protect against disease by producing antibodies and performing phagocytosis. In addition, blood also contains interferons and complement proteins that help protect against disease.

Constituents of blood

Blood has a characteristic constituency of living cells suspended in a plasma matrix. It is a sticky, viscous, dark red, opaque fluid consisting of 55% plasma and 45% cells. More than 99% of the cellular component consists of erythrocytes (red blood cells or RBCs). White cells and platelets are present in small quantities. Blood also contains many chemicals in suspension. If blood is exposed to the air it solidifies into a clot and exudes a clear fluid called serum.

Plasma

Plasma is the liquid portion of the blood which acts as the transport medium of substances being carried in the blood. Water comprises approximately 90% of the plasma volume, with the remainder containing protein 8%, inorganic ions 0.9% and organic substances 1.1%. The characteristic straw colour of plasma is produced by bilirubin, the waste product of haemoglobin breakdown. Table 16.2 outlines the constituents and function of plasma.

| Constituent | Function |

|---|---|

| Water | Transport medium of nutrients, wastes, gases Heat distributor |

| Plasma protein—albumin | Transports many substances Large contribution to colloid oncotic pressure |

| Plasma protein globulins—α and β | Transport substances, involved in clotting |

| Plasma protein globulins—γ | Antibodies |

| Plasma protein—fibrinogen | Inactive precursor for fibrin |

| Electrolytes | Osmotic distribution of fluid between compartments |

Serum is blood plasma without fibrinogen and other clotting factors. Protein molecules are too large to pass into the interstitial fluid at the capillary beds; therefore, there is a higher protein content in plasma than in interstitial fluid (i.e. 8% compared with 2%). Most of the protein that does pass into interstitial fluid is taken up by the lymphatic system and returned to the blood. The main plasma proteins are presented in Table 16.3.

| Name | Origin | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin | Synthesised in the liver | 60 |

| Fibrinogen | Synthesised in the liver | 4 |

| Globulins α and β | Synthesised in the liver | 36 |

| Globulin γ | Synthesised in the immune system | Trace |

The functions of plasma proteins are to:

• Prevent fluid loss from blood to tissues by exerting colloid osmotic ( oncotic) pressure. This is mainly due to the presence of the protein albumin. If plasma protein levels fall due to either reduced production or loss from the blood vessels then osmotic pressure is also reduced. Fluids will then move into the tissues (oedema) and body cavities. This may occur in diseases of the liver and kidneys, burns, inflammation and allergic disorders.

• Transport bound substances to prevent them from being metabolised until they reach their target tissue: for instance, albumin binds bilirubin. Some substances can displace others and compete for binding sites. An example of this is the displacement of bilirubin from albumin by aspirin or sulphonamides.

• Aid in clotting and fibrinolytic activities.

• Assist in prevention of infection: γ-globulins (also known as immunoglobulins—see Ch. 29) function as specific antibodies for specific protein antigens such as microbial agents and pollen.

• Help regulate acid–base balance by acting in buffering systems.

• Act as a protein reserve that forms part of the amino acid pool.

• Contribute about 50% to the total viscosity of blood.

Other proteins found in the blood in small quantities are hormones, enzymes and most of the clotting factors. There is also a series of plasma proteins called complement that assist in the inflammatory and immune mechanisms. Albumin is the smallest of the plasma proteins with a molecular mass of 69 000 and is just too large to pass through the capillary walls in normal circumstances. If the glomerular capillaries in the kidney are damaged, albumin can be lost from the blood in large quantities.

The cellular components of blood

Three major cell types are present in blood, each having a very different function: red cells ( erythrocytes), white cells ( leucocytes) and platelets ( thrombocytes) (Table 16.4).

| Constituent | Function |

|---|---|

| Erythrocytes (red cells) | Oxygen and carbon dioxide transport |

| Leucocytes (white cells) | Defence against micro-organisms |

| Platelets | Haemostasis |

Under normal circumstances, the proportions of these cells remain constant within narrow limits. However, the body may adjust these levels to maintain health. A simple routine test can measure the cellular content of blood. This is normally carried out on most people at some point in their life, either as part of health screening or to diagnose illness.

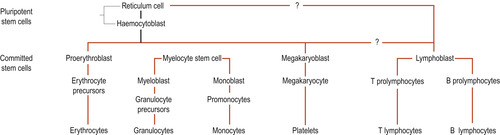

Haemopoiesis is the term used for blood cell formation. Embryonic blood cells appear in the bloodstream as early as the 3rd week of development. All blood cell types are descended from a single type of bone marrow cell called a pluripotent stem cell or haemocytoblast, which is an undifferentiated cell capable of giving rise to the precursor of any of the blood cell types. These include the red cells and megakaryocytes (leading to platelets). The pluripotent stem cells branch to form myeloid stem cells, which leads to the production of granulocytes and monocytes in the bone marrow. Lymphoid stem cells leave the bone marrow to reside in the lymphoid tissues and produce lymphocytes. Each person has about 1500 g of red bone marrow in the body. Two-thirds of the production is white cells and one-third is red cells (Fig. 16.1).

|

| Figure 16.1 Summary of the major stages of haemopoiesis. (From Hinchliff S M, Montague S E 1990, with permission.) |

Red blood cells

The major function of erythrocytes or red blood cells (RBCs) is the carriage of oxygen, picked up in the lungs, to all the cells of the body. Erythrocytes contain large amounts of the protein haemoglobin with which oxygen and, to a lesser extent, carbon dioxide reversibly combine. The shape and size of the red cells are significant for this function. Erythrocyctes are biconcave discs (circular and flattened, thinner in the middle than round the edge) and are 7.5 micrometres (μm) in diameter. This provides a high surface-to-volume ratio well suited to the exchange of gases, and allows the volume of the cell to readily alter with the osmotic shifts of water between cell and plasma. The plasma membrane is strong and conveniently pliant, which allows the cells to become deformed as they squeeze through torturous and narrow capillary vessels whose diameter may be smaller than the RBC.

Erythrocytes are normally measured per cubic mm (mm 3, which is the same as 1 μl of blood) and average 5 million. This value may also be reported as 5.0 × 10 12/L. Women have a range of 4.3–5.2/mm 3 and men have a higher range of 5.1–5.8/mm 3 (Table 16.5). RBCs are the main cellular contributor to blood viscosity. Therefore any increase in this range will also raise the viscosity of blood, which may occur in circumstances such as a slower flow of blood or a move to an area of high altitude. Any subsequent decrease, such as is seen in normal pregnancy, will lower viscosity and blood will flow more rapidly.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Red cell count | 5.1–5.8 × 10 12/L (males) 4.3–5.2 × 10 12/L (females) |

| Haemoglobin | 13–18 g/dl (males) 12–16 g/dl (females) 14–20 g/dl (infants) |

| Mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | 32 g/dl |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) | 85 femtolitres (1 fl = 1000 million millionths of a litre) |

Erythrocytes are completely dedicated to the transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Haemoglobin (Hb) is the oxygen-carrying capacity of the erythrocytes and is measured in grams per 100 ml of blood (g/100 ml or g/dl). The normal range of values is 14–20 g/dl in infants, 12–16 g/dl in females and 13–18 g/dl in males. Haemoglobin also picks up about 20% of carbon dioxide (CO 2) returning from the tissues to form carbaminohaemoglobin, but most of the CO 2 is in solution in the blood.

Haemoglobin

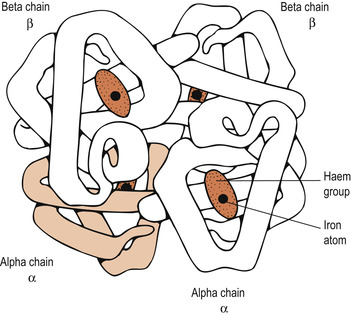

Haemoglobin is a red-coloured pigment found in red cells. Each red cell contains 30 pg (picograms) of haemoglobin. This is reported as the mean cell haemoglobin or MCH. Another measure reported is the mean cell concentration of haemoglobin (MCHC), which is 32 g/dl. Haemoglobin is made up of the protein globin bound to the red haem pigment. Globin is rather complex. It consists of four polypeptide chains—two alpha (α) and two beta (β)—each bound to a ring-like haem group (Fig. 16.2). Each haem contains one iron ion (Fe 2+) that can combine reversibly with one oxygen molecule to form the bright red oxyhaemoglobin (HbO 2). The iron–oxygen interaction is very weak and the two can be easily separated without any damage. Once the oxygen has been released in the tissues, it becomes darker red and is known as deoxyhaemoglobin.

|

| Figure 16.2 The structure of haemoglobin. Haemoglobin is a protein with four subunits (two α polypeptides and two β polypeptides). Each subunit contains a haem group with an iron atom. (From Jones et al, with permission.) |

Each haemoglobin molecule can carry four molecules of oxygen. These are picked up one at a time and each binding changes the configuration of globin and increases the affinity of the haemoglobin molecule for oxygen. The affinity for the fourth molecule of oxygen is 20 times that of the first affinity. This aspect of oxygen uptake will be examined in greater detail when respiration is considered.

The pigment haem is made up of ring-shaped organic molecules called pyrrole rings. Four of these join together to form a larger ring and the nitrogen atom of each pyrrole ring holds a ferrous iron atom centrally. The globin proteins consist of long chains of amino acids. There are four types of globin chain, each with slight differences in amino acids: α (alpha), β (beta), δ (delta) and γ (gamma). They can be varied in pairs to form different types of haemoglobin, three of which are found normally:

• HbA, the major adult haemoglobin: 2α2β

• HbA 2, the minor adult haemoglobin: 2α2β

• HbF, fetal haemoglobin: 2α2γ.

At birth HbF makes up two-thirds of haemoglobin content and HbA one-third. From the age of 5 years the adult ratio is established, i.e. HbA is greater than 95%, HbA 2 is less than 3.5% and HbF is less than 1.5%. Other fetal haemoglobins have substitutions for the β chains which can persist and may be life-saving in thalassaemia. Abnormal β chains are made in sickle-cell disorders.

Formation of erythrocytes

Mature red blood cells develop from haemocytoblasts within the erythroid tissue in the bone marrow. After 3–5 days the cells pass into the circulation as cells called reticulocytes because they still contain rough endoplasmic reticulum and clumped ribosomes. These structures disappear when the cell is mature, which normally takes 4 days. Three or four mitotic cell divisions are involved so that each haemocytoblast gives rise to 8 or 16 red cells. There is a gradual build-up of haemoglobin made at the ribosomes which appears in the cell. Other organelles and the nucleus are extruded from the cell. There is a reduction in cell size and a change in cell shape. Reticulocytes normally comprise less than 2% of the red cells in the blood of an adult. The formation of erythrocytes is called erythropoiesis and the dietary substances required are summarised in Table 16.6.

| Substance | Utilisation |

|---|---|

| Protein | Synthesis of the globin part of haemoglobin and for cellular proteins |

| Iron | Contained in the haem portion of haemoglobin |

| Vitamin B 12 (hydroxycobalamin) | Needed for DNA synthesis |

| Folic acid | Needed for DNA synthesis |

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | Facilitates absorption of iron |

The life span of red cells

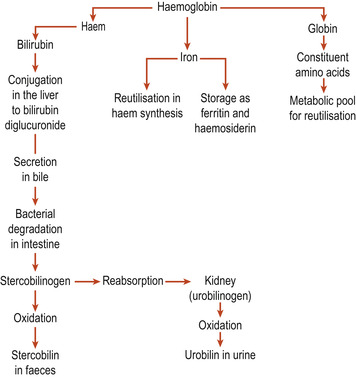

About 1% of erythrocytes are replaced each day. Production is stimulated by the hormone erythropoietin, which originates in the kidney. This is a glycoprotein produced when the kidney cells are hypoxic: for example, during haemorrhage, haemolytic crises, at altitude and following exercise. Erythropoietin can only stimulate committed cells and there will be an increase in reticulocytes in the blood if the need is drastic. Red blood cells live for about 120 days and are finally ingested and destroyed by macrophages, mainly in the spleen. As the cells circulate, their plasma membrane becomes progressively more damaged until it ruptures. Having no nucleus, they have no mechanism of self-repair. They are fragmented to produce protein and haem, which is mostly reclaimed in the body stores for reuse. The remainder of the haem portion is degraded and bilirubin is excreted as bile (Fig. 16.3).

|

| Figure 16.3 A summary of haemoglobin breakdown. (From Hinchcliff S M, Montague S E 1990, with permission.) |

Very defective cells such as those found in sickle-cell disease may be haemolysed in the circulation. The haemoglobin, which has a molecular mass of 68 000 and is small enough to be excreted in the urine, is released into the plasma. Special plasma proteins called haptoglobins bind to free haemoglobin to form larger molecules and prevent it from being excreted. If this mechanism becomes saturated, haemoglobin will appear in the urine ( haemoglobinuria).

Iron metabolism

Absorption

A typical British mixed diet usually contains about 14 mg of iron daily but normally only 1–2 mg (5–10%) is absorbed. The composition of the diet determines how much iron is available for absorption (Robinson 2002). There are two distinct forms for absorption: iron attached to haem and inorganic iron. Iron attached to haem is found in the haemoglobin and myoglobin protein found in animal products. It is absorbed much more efficiently than non-haem iron and is not affected by factors affecting the absorption of non-haem iron. In most foods, iron is present in its ferric form and has to be converted to ferrous iron in order to be absorbed.

Absorption is enhanced if reducing agents that can aid this conversion are available. Hydrochloric acid found in the gastric juice performs this function, as can ascorbic acid (vitamin C). In grain foods iron forms a complex with phytates and only small amounts of soluble iron are available. The iron in eggs is bound to phosphates in the yolk and is poorly absorbed. The amount of iron absorbed depends on the rate of red cell production, the extent of iron stores, the content of the diet and whether or not iron supplements are given. Intestinal absorption of iron is facilitated when there is erythroid hyperplasia, rapid turnover of iron and a high concentration of unsaturated transferrin, as occurs in pregnancy.

Serum iron, transferrin and total iron-binding capacity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree