Chapter Four. The female reproductive system

Sexual differentiation

In the early embryo there is no anatomical difference internally or externally prior to the 7th week of development. Two pairs of genital ducts are present: the paramesonephric or Müllerian ducts with the potential to develop into female genitalia and the mesonephric or Wolffian ducts with the potential to develop into male genitalia. A Y chromosome gene called SRY (sex-determining region Y gene) is expressed in male embryos (Jones 2002). Under its influence, testes and functioning Sertoli cells are formed in the presence of testosterone (Ch. 5).

If the embryo is XX, ovaries will form and the female ducts develop into female genitalia. The ducts that are not required to develop degenerate. This influence on the indifferent tissues (Moore & Persaud 2008) leads to homologous structures, i.e. structures developed from the same origin. Examples include testis and ovary, penis and clitoris. Rarely, instant recognition of the sex of the baby is difficult or impossible without genetic testing.

Anatomy of the female reproductive tract

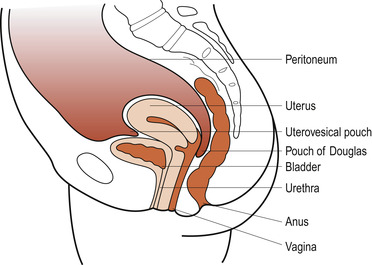

The soft tissues forming the female internal genitalia are situated in the pelvic cavity. Although the organs are separate structures, they form a continuous tract. The organs are: vulva, vagina, uterus and cervix, uterine tube and ovary. Figure 4.1 is a diagram of the whole female reproductive tract.

|

| Figure 4.1 The pelvic organs in sagittal section. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

The vulva

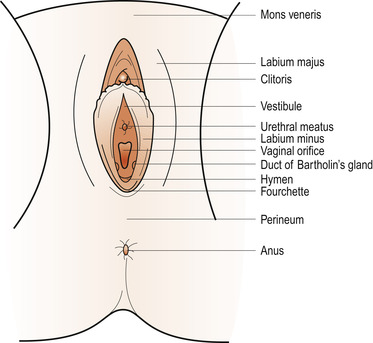

Figure 4.2 shows the external organs that constitute the vulva, each of which will be described in turn.

|

| Figure 4.2 The external genitalia. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

The labia majora

These are two folds containing sebaceous and sweat glands embedded in adipose and connective tissue. They are covered with skin and form the lateral boundaries of the vulval cleft. They are homologues of the scrotum. They unite anteriorly to form the mons veneris, an adipose pad over the symphysis pubis. Hair covers the mons veneris and terminates in a horizontal upper border. Posteriorly the labia majora unite to form the posterior commissure. Hair grows on the outer surface of the labia majora but not on the inner surface.

The labia minora

These are two delicate folds of skin containing some sebaceous glands but no adipose tissue. On the medial aspect keratinised skin epithelium changes to squamous epithelium with many sebaceous glands. Anteriorly, the labia minora split into two parts. One passes over the clitoris to form its prepuce and the other passes beneath the clitoris to form a homologue of the frenulum in the male. Posteriorly, the two labia minora unite to form the fourchette. The size of the labia minora varies between women but this is of no significance.

The clitoris

This is the homologue of the male penis. It is composed of erectile tissue and can enlarge and stiffen during sexual excitement. Only the glans and prepuce are normally visible but the corpus can be palpated as a cord-like structure along the lower surface of the symphysis pubis.

The vestibule

This is the cleft between the labia minora onto which open:

• The urethral meatus.

• The vaginal orifice.

Bartholin’s glands

Bartholin’s glands are two pea-sized glands embedded in connective tissue that are connected to the vestibule by ducts that are 2 cm long. These glands are homologues of Cowper’s glands in the male. The ducts are lined with columnar epithelium which produces a mucoid secretion onto the vestibule for lubrication during coitus.

Blood supply

The vulva is very vascular, receiving its arterial supply from the internal pudendal arteries, which are branches of the internal iliac arteries, and the external pudendal arteries, which are branches of the femoral arteries. Venous drainage is usually by corresponding veins which accompany the arteries but, from the clitoris, a plexus of veins joins the vaginal and vesical venous plexi.

Lymphatic drainage

Nerve supply

Branches of the pudendal nerve and perineal nerve supply the vulval structures.

The vagina

The vagina is a fibromuscular sheath and a potential canal extending from the vulva to the uterus. The walls are normally in apposition. The widest diameter of the vagina is anteroposterior in the lower one-third and transverse in the upper two-thirds. This is important to remember when inserting vaginal speculae. It runs upwards and backwards from the vestibule at 85% to the horizontal, which is parallel to the plane of the pelvic brim when the woman is standing erect. The vagina is surrounded and supported by the pelvic floor muscles.

The posterior wall ends blindly to form the vault of the vagina and is 9 cm long. The cervix projects into the anterior wall of the vagina, shortening it to 7 cm in length. This cervical projection divides the vault of the vagina into four fornices, shallow anterior and lateral fornices and a more capacious posterior fornix.

The entrance to the vagina is partially covered by the membranous hymen which has a few perforations to allow menstrual flow. This membrane varies in elasticity and is usually torn at the first coitus and more so at the first birth. Imperforate hymen is a possible cause of failure to menstruate. Once ruptured, remnants are left called carunculae myrtiformes. The walls of the vagina fall into transverse folds or rugae to allow for distension. These spread out from two longitudinal columns which run sagittally in the anterior and posterior walls.

Layers of the vagina

• Stratified squamous non-keratinised epithelium 10–30 cells deep rests on a basement membrane to form the inner lining of the vagina. This is continuous with the epithelium of the infravaginal cervix. The cells are divided into three layers, derived from the basement membrane and changing as they near the surface. These are the parabasal cells, intermediate cells and superficial cells.

• A layer of vascular connective tissue contains elastic tissue, nerves, lymphatic and blood vessels.

• An involuntary muscle coat whose inner muscle fibres are more oblique than circular while the outer are longitudinal. The vagina varies in size, mainly as a function of muscle tone and contraction in the pelvic floor muscles which are under voluntary control.

• Fascia or loose connective tissue surrounds the vagina.

The epithelium changes with the ovarian and menstrual cycles. There is further development and differentiation during pregnancy in response to circulating oestrogens, progesterone and androgens. The vaginal epithelium does not secrete mucus but secretions seep between the cells to moisten the vagina. Superficial cells and some intermediate cells contain glycogen. Superficial cells are continuously exfoliated and release their glycogen which is metabolised by Döderlein’s bacillus, producing lactic acid as a waste product. This results in a normal vaginal acid medium of 4.5, preventing pathogenic organisms from invading. The cells can also absorb drugs, in particular oestrogens.

Relations

The lower half of the anterior wall is in contact with the urethra to which it is tightly bound. The upper half is in close contact with the base of the bladder. The lower third of the posterior wall is separated from the anal canal by the perineal body, the middle third is in apposition with the rectum and the upper third with a pouch of peritoneum called the pouch of Douglas. Laterally the upper third of the vagina is supported by pelvic connective tissue, the middle third by the levatores ani and the lower third by the bulbocavernosus muscle.

Blood supply

Arterial supply is from the vaginal and uterine arteries, which are both branches of the internal iliac artery. Venous drainage is by rich venous plexi in the muscular layer. These communicate with pudendal, vesical and haemorrhoidal plexi and then to the internal iliac vein.

Nerve supply

Nerve supply to voluntary vaginal muscle is via the pudendal nerve.

Vaginal functions

• Escape of menstrual blood flow.

• Coitus with entry of the male penis.

• Birth of the fetus, placenta and membranes.

The non-pregnant uterus

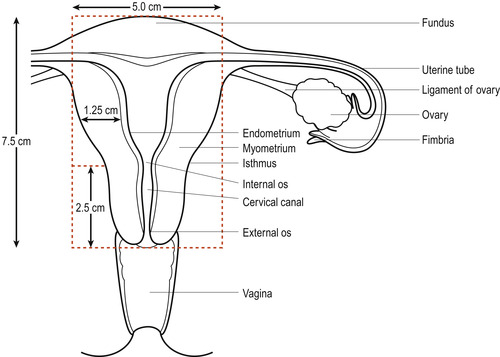

The uterus develops from the fusion of the two embryonic Müllerian ducts (Johnson 2007). It is a thick-walled, muscular, hollow, pear-shaped organ flattened in its anteroposterior diameter. Its lower third forms the cervix which projects into the vault of the vagina through its anterior wall. The uterus lies in the pelvic cavity in an anteverted and anteflexed position. Its normal measurements are shown in Table 4.1.

| Dimension | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Length, including cervix | 7.5 cm |

| Breadth | 5.0 cm |

| Depth | 2.5 cm |

| Average thickness of walls | 1.5 cm |

| Weight | 60 g |

Structure

The uterus (Fig. 4.3) consists of the body which is 5 cm long, the narrow isthmus 0.5 cm long and the cervix 2.5 cm long. The fundus is the area above and between the uterine tubes (Fallopian tubes), and the junction between each uterine tube and the uterus is called the cornu (plural cornua). A constriction at the upper end of the isthmus is called the anatomical internal os and where the endometrium meets the columnar cervical epithelium is called the histological internal os. The cavity has a triangular shape when viewed in coronal section and a capacity of about 10 ml.

|

| Figure 4.3 The uterus and the left uterine tube and ovary. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Although the cervix is continuous with and part of the uterus, it differs in its structure and function from the body of the uterus and will be described separately. The cervix is barrel-shaped and penetrated by the cervical canal. It is 2.5 cm long and separated from the body of the uterus by the isthmus. It is divided into two equal parts:

BOX 4.1

BOX 4.1

1. The supravaginal cervix lies above the vaginal vault and is surrounded by pelvic fascia, the parametrium, except posteriorly where it is in apposition with the pouch of Douglas.

2. The cone-shaped infravaginal cervix projects into the vagina and is covered by stratified squamous epithelium, continuous with the vaginal epithelium. It joins the columnar epithelium of the cervical canal at the external os, a site called the squamocolumnar junction, an important site of cellular change (see Box 4.1).

BOX 4.1

BOX 4.1 THE SQUAMOCOLUMNAR JUNCTION AND CERVICAL SCREENING

The squamocolumnar junction is between the columnar epithelium of the cervical canal and the squamous epithelium continuous with the vaginal epithelium. This may be an abrupt transformation but sometimes the two tissue types merge in a transformation zone which is the usual site for cervical carcinoma to arise. The position of this junction is determined by the amount of stroma which is influenced by the levels of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone.

Oestrogen softens the cervical collagen by binding water to the molecules. This increases the volume of stroma which causes the clefts and tunnels to unfold. The squamocolumnar junction is displaced downwards and out of the cervical canal, an event called eversion. Exposure of the columnar epithelium causes the tissues to hypertrophy ( squamous metaplasia) leading to the development of the transformation zone.

In some women the cervical epithelium seems unstable, and cells with nuclear dyskaryosis (abnormal appearance of the nucleus) and cellular dysplasia (abnormal cell growth) are likely to lead to cervical carcinoma. These abnormalities are due to an infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV) types 16, 18 and 6. HPV can be a cause of genital warts. Epidemiological evidence has indicated that up to 30% of sexually active women have been affected by HPV by the age of 30.

Early recognition of these precancerous changes allows surgical treatment to be successful so that screening women on a regular basis can be life-saving. The technique is called cervical exfoliative cytology and is offered to antenatal patients who have not been recently screened. A specially shaped spatula such as an Ayres spatula is used to obtain cells from both outside and inside the cervical canal.

The cells are examined under a microscope and reported as:

1. Unsatisfactory: insufficient cells or incorrect processing of the slide.

2. Inflammatory or inconclusive: cells distorted by other infections such as Monilia.

3. Normal.

4. Mild dyskaryosis (CIN1) (CIN means cervical intraepithelial carcinoma).

5. Moderate dyskaryosis (CIN2).

6. Severe dyskaryosis (CIN3).

Over 90% of smears will be reported as normal. Categories 1, 2 and 4 need a repeat smear after 3–4 months following treatment for infection if necessary. Categories 5 and 6 need direct vision examination by colposcopy followed by a tissue biopsy. The extent of surgical treatment will depend on the results of the biopsy and whether the woman wishes to have more children. It will vary from the destruction of the abnormal cells by laser or cryosurgery to cone biopsy to hysterectomy. More serious and likely to lead to death of the woman is invasive carcinoma of the cervix where the cancer has spread beyond the epithelial tissues.

Lining of the body (corpus)

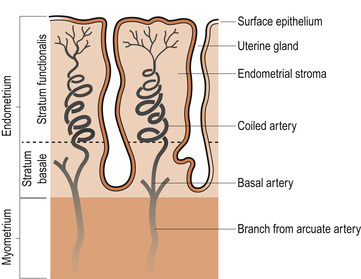

The mucous lining or endometrium builds up from a layer of basal cells. It consists of stroma (connective tissue component of an organ) covered by a layer of ciliated cuboid cells. This layer dips down into the stroma to form mucus-secreting tubular cells opening into the uterine cavity (Fig. 4.4). The thickness varies depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle and is thinnest at the isthmus.

|

| Figure 4.4 The vascular supply to the endometrium. (From Hinchliff S M, Montague S E 1990, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Lining of the cervix

The spindle-shaped cervical canal connects the uterine cavity at the internal os with the vagina at the external os. The canal is lined by columnar mucus-secreting epithelium thrown into anterior and posterior folds from which circular folds radiate like branches from a tree trunk (the arbour vitae or tree of life). The epithelium dips into the stroma in a complex system of crypts and tunnels separated by ridges of stroma consisting of 80% collagen, 10% muscle fibres and 10% blood vessels. Compound racemose glands secrete cervical mucus that varies in quality and quantity under the influence of the sex hormones.

Muscle layer

The muscle layer or myometrium is made up of bundles of smooth muscle fibres. The outer longitudinal layer and the inner circular layer are not well developed in the non-pregnant uterus so that most fibres run obliquely and interlace to surround blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The proportion of muscle begins to diminish in the isthmus, being replaced by connective tissue until it reaches the 10% muscle content of the cervix.

Peritoneal layer

The peritoneal layer is a double serosal layer known as the perimetrium. It covers the anterior and posterior surfaces but is absent from the narrow lateral surfaces. It is reflected off the uterus onto the superior surface of the bladder at the level of the anatomical internal os; this is important for understanding the technique of lower segment caesarean section.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree