Chapter Twenty-Eight. The endocrine system

Introduction

The nervous system (Ch. 26 and Ch. 27) is the rapid controller of the body whereas the endocrine system provides a much slower control. By coordinating the body’s internal physiology and modifying cell function, the endocrine system helps it to adapt to external environmental changes (Hinson et al 2007). The nervous system and the endocrine system are closely related with the hypothalamus providing a major link between them. Each gland will be discussed in turn.

The hypothalamus

The hypothalamus controls the function of the endocrine glands and has wider links with parts of the nervous system. The hypothalamus is therefore a neuroendocrine organ, producing both releasing and inhibiting hormones to influence the production of anterior pituitary gland hormones. Endocrine glands include the thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal and pineal glands.

Other organs produce hormones, including the pancreas (Ch. 22), ovaries (Ch. 4), testes (Ch. 5) and placenta (Ch. 12). Functions of endocrine glands include reproduction, growth and development, mobilisation of body defences against stress, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, blood nutrient content, regulation of cell metabolism and energy balance. Tissue responses to hormones may take only a few seconds or may take days.

Hormones

Hormones are regulatory molecules synthesised in specialist cells which may be collected into distinct endocrine glands or found as single cells within organs, e.g. the gastrointestinal tract. Hormone-secreting glands are arranged in cords and branching networks to maximise contact between cells and the capillaries that receive their secretions directly. Exocrine glands pass their products through ducts into a body cavity or onto the surface of the skin.

Hormones affect tissues by binding to specific receptors on the surface of target cells. Some hormones act locally and are secreted into the extracellular fluid without entering the bloodstream. They affect adjacent cells of a different type ( paracrine) or on the same cell type ( autocrine) (Guyton & Hall 2006).

Types of hormones

Hormones are classified into three groups: those derived from the amino acid tyrosine; polypeptide and protein hormones; and steroid hormones. Most are polypeptides (Guyton & Hall 2006).

Tyrosine-derived hormones

Hormones derived from tyrosine include adrenaline (epi-nephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine), dopamine and the thyroid hormones thyroxine and tri-iodothyronine.

Protein and polypeptide hormones

These hormones include parathyroid hormone, oxytocin, vasopressin, insulin, the anterior pituitary gland glycoprotein hormones such as gonadotrophins, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone and gastrointestinal hormones such as secretin and gastrin.

Steroid hormones

Steroids, which are derived from cholesterol, include cortisol and aldosterone from the adrenal cortex and the sex hormones testosterone, progesterone and oestrogen.

Target cells

Hormones circulate to nearly all tissues but can only influence cells with specific receptors in their plasma membranes. Some only influence a few tissues; for example, adrenocorticotrophic hormone can only influence certain adrenal cortical cells. Others such as thyroxine are essential for the metabolism of all cells.

Water-soluble hormones such as peptides and catecholamines are dissolved in plasma and transported to their target cells diffusing out of the capillaries to reach their targets. Thyroxine and the steroid hormones are bound to specific plasma carrier proteins and are inactive until they dissociate from their carriers.

Metabolic clearance rate is millilitres of plasma cleared of a hormone per minute (ml/min). This may be achieved by:

• Metabolic destruction by the tissues.

• Binding with the tissues.

• Excretion in bile by the liver.

• Excretion in urine by the kidneys.

Most peptide hormones and catecholamines are water-soluble and are degraded by enzymes in the blood to be excreted by the kidneys and liver. The actions of some hormones are short-lived, developing their full action within a few seconds. Hormones bound to plasma proteins may stay in the blood for hours or even days. Some such as thyroxine and growth hormone may require months to achieve their full effects. Cellular activity depends on blood levels of the hormone, the number of cell-surface receptors and the affinity of the receptor for the hormone. Hormone receptors are large proteins and there are thousands of receptors on a cell, each specific for a single hormone. Different types of hormone receptors are located:

1. In or on the surface of the cell membrane, mainly for protein, peptide and catecholamine hormones.

2. In the cell cytoplasm, mainly for steroid hormones.

3. In the cell nucleus, mainly for thyroxine.

Cell-surface receptors

There are two major groups of cell-surface receptors: single-transmembrane domain receptors, a pathway utilised by hormones such as insulin and prolactin; and G-protein coupled receptors (seven-transmembrane domain receptors), so called because the receptor structure crosses the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane seven times (Hinson et al 2007).

Cytoplasm receptors

Most amino acid-based hormones cannot penetrate cell membranes and have to utilise intracellular second messengers such as cyclic AMP. Others involve a different second messenger: calcium, which either acts directly by altering the activity of specific enzymes or indirectly by binding to an intracellular protein calmodulin.

Nuclear receptors

Steroid and thyroid hormones bind to protein members of a superfamily of intracellular receptors. They are lipid-soluble and diffuse across plasma membranes to gain access to intracellular receptors in the cytosol or nucleus. Responses to steroid and thyroid hormones are sluggish compared with hormones which act via cell-surface receptor/second messenger systems.

The mechanisms of hormone action

Hormones increase or decrease cellular activity by producing one or more of the following (Marieb 2008):

Regulators of receptors

Target cells may make more receptors in response to high levels of hormones, this is up-regulation, or respond to high hormone levels by losing receptors, down-regulation. Hormones may also influence receptors responsive to other hormones. The presence of progesterone causes a loss of oestrogen receptors but oestrogen causes an increase in progesterone receptors, causing the cells to have an enhanced ability to respond to progesterone.

Control of hormone release

The synthesis and release of hormones depends on inhibition by negative feedback. Hormone secretion is triggered by a stimulus and blood levels rise until they reach the required level when further hormone release is inhibited. This maintains blood levels within a narrow range. Stimuli can be hormonal, humeral or neural:

• Hormonal stimulus: hypothalamic releasing and inhibiting hormones regulate the pituitary gland hormones, some of which in their turn induce other glands to secrete their hormones.

• Humeral stimulus: changing blood levels of ions and nutrients; for example, the production of parathyroid hormone is prompted by decreasing blood calcium levels.

• Neural stimuli: for example, the release of catecholamines by the sympathetic nervous system in response to stress.

The pituitary gland

The pituitary gland or hypophysis is a small ovoid gland weighing 500 mg and situated in the sella turcica of the sphenoid bone. It has a stalk called the infundibulum, which connects it to the hypothalamus, and two lobes:

• The posterior lobe ( neurohypophysis) consists of nerve fibres and neuroglia and is a downwards growth of the hypothalamus. It does not manufacture hormones but stores hypothalamic hormones, releasing them as necessary.

• The anterior lobe ( adenohypophysis) is composed of glandular tissue and manufactures and releases its own hormones.

The gland has a rich blood supply derived from the internal carotid artery via superior and inferior hypophyseal branches. Venous drainage is into the dural venous sinuses. The gland is susceptible to blood loss, particularly in pregnancy.

The pituitary–hypothalamic axis

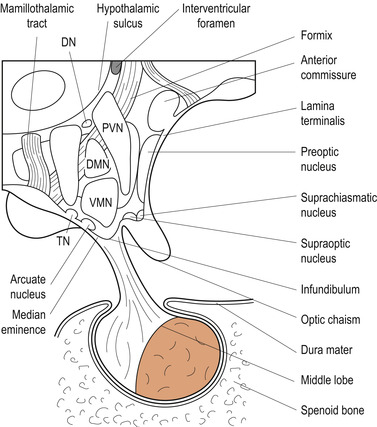

A nerve bundle called the hypothalamic–hypophyseal tract runs through the infundibulum (Fig. 28.1). The tract neurons are situated in two groups of nuclei in the hypothalamus:

1. Oxytocin is secreted from the hypothalamic paraventricular nuclei and antidiuretic hormone from the supraoptic nuclei. These hormones are transported along axons to their terminals on the posterior pituitary lobe.

2. The hypothalamic–hypophyseal nuclei are responsible for anterior pituitary function. There is no direct neural connection between the adenohypophysis and the hypothalamus. The vascular hypophyseal portal system carries hypothalamic releasing and inhibiting hormones to the anterior pituitary lobe.

|

| Figure 28.1 Hypothalamic nuclei and hypophysis, viewed from the right side. DN, dorsal nuclei; DMN, dorsomedial nucleus; MB, mamillary body; PN, posterior nucleus; PVN, periventricular nucleus; TN, tuberomamillary nucleus; VMN, ventromedial nucleus. (From Fitzgerald M J T 1996, with permission.) |

Regulation of function

A number of hypothalamic neurohormones regulate anterior pituitary function. They have short half-lives in the circulation and act rapidly on specific anterior pituitary cells (Table 28.1).

| Name | Major function(s) |

|---|---|

| Thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH) | Stimulates release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin (PRL) |

| Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) | Stimulates release of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) |

| Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) | Stimulates release of growth hormone (GH) |

| Growth hormone-release inhibiting hormone (somatostatin, SMS) | Inhibits release of GH, gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), glucagons, insulin, TSH and PRL |

| Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) | Stimulates release of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) |

| Dopamine (DA) | Inhibits release of PRL |

Anterior pituitary hormones

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree