Chapter 12

The digestive system

Organs of the digestive system

Basic structure of the alimentary canal

Large intestine, rectum and anal canal

Summary of digestion and absorption of nutrients

Effects of ageing on the digestive system

12.1 The alimentary canal 287

12.2 Peristalsis 289

12.3 Oesophagus 296

12.4 Mouth: chewing and preparation for swallowing 297

12.7 Stomach: secretion of pepsinogen 300

12.8 Small intestine 302

12.9 Summary of digestion 305

12.10 Large intestine 306

12.11 Hepatic portal circulation 309

12.12 Biliary tract and secretion of bile 312

12.13 Factors influencing metabolic rate 314

12.14 Glycolysis 315

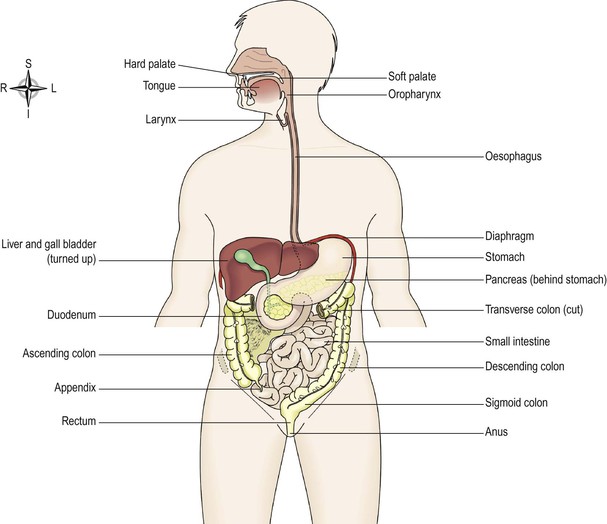

The digestive system describes the alimentary canal, its accessory organs and a variety of digestive processes that prepare food eaten in the diet for absorption. The alimentary canal begins at the mouth, passes through the thorax, abdomen and pelvis and ends at the anus (Fig. 12.1). It has a basic structure which is modified at different levels to provide for the processes occurring at each level (Fig. 12.2). The digestive processes gradually break down the foods eaten until they are in a form suitable for absorption. For example, meat, even when cooked, is chemically too complex to be absorbed from the alimentary canal. Digestion releases its constituents: amino acids, mineral salts, fat and vitamins. Digestive enzymes (p. 28) responsible for these changes are secreted into the canal by specialised glands, some of which are in the walls of the canal and some outside the canal, but with ducts leading into it. ![]() 12.1

12.1

After absorption, nutrients provide the raw materials for the manufacture of new cells, hormones and enzymes. The energy needed for these and other processes, and for the disposal of waste materials, is generated from the products of digestion.

The activities of the digestive system can be grouped under five main headings.

Ingestion.

This is the taking of food into the alimentary tract, i.e. eating and drinking.

Propulsion.

This mixes and moves the contents along the alimentary tract.

Absorption.

This is the process by which digested food substances pass through the walls of some organs of the alimentary canal into the blood and lymph capillaries for circulation and use by body cells.

Elimination.

Food substances that have been eaten but cannot be digested and absorbed are excreted from the alimentary canal as faeces by the process of defaecation.

The fate of absorbed nutrients and how they are used by the body is explored and the effects of ageing on the digestive system are considered. In the final section disorders of the digestive system are explained.

Organs of the digestive system (Fig. 12.1)

Alimentary canal

Also known as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, this is essentially a long tube through which food passes. It commences at the mouth and terminates at the anus, and the various organs along its length have different functions, although structurally they are remarkably similar. The parts are:

Accessory organs

Various secretions are poured into the alimentary tract, some by glands in the lining membrane of the organs, e.g. gastric juice secreted by glands in the lining of the stomach, and some by glands situated outside the tract. The latter are the accessory organs of digestion and their secretions pass through ducts to enter the tract. They consist of:

The organs and glands are linked physiologically as well as anatomically in that digestion and absorption occur in stages, each stage being dependent upon the previous stage or stages.

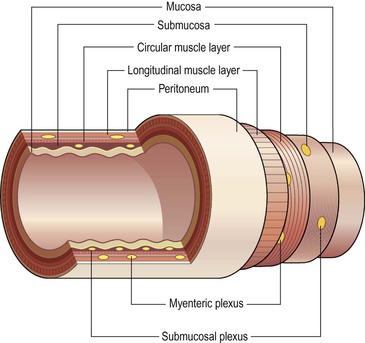

Basic structure of the alimentary canal (Fig. 12.2)

The layers of the walls of the alimentary canal follow a consistent pattern from the oesophagus onwards. This basic structure does not apply so obviously to the mouth and the pharynx, which are considered later in the chapter.

In the organs from the oesophagus onwards, modifications of structure are found which are associated with specific functions. The basic structure is described here and any modifications in structure and function are described in the appropriate section.

The walls of the alimentary tract are formed by four layers of tissue:

Adventitia or serosa

This is the outermost layer. In the thorax it consists of loose fibrous tissue and in the abdomen the organs are covered by a serous membrane (serosa) called peritoneum.

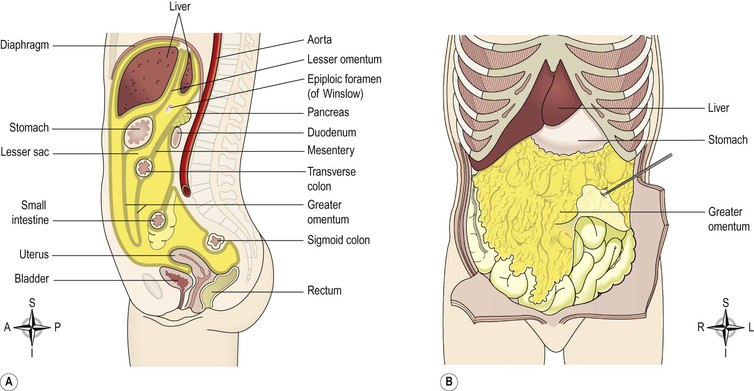

Peritoneum

The peritoneum is the largest serous membrane of the body (Fig. 12.3A). It is a closed sac, containing a small amount of serous fluid, within the abdominal cavity. It is richly supplied with blood and lymph vessels, and contains many lymph nodes. It provides a physical barrier to local spread of infection, and can isolate an infective focus such as appendicitis, preventing involvement of other abdominal structures. It has two layers:

• the parietal peritoneum, which lines the abdominal wall

• the visceral peritoneum, which covers the organs (viscera) within the abdominal and pelvic cavities.

The parietal peritoneum lines the anterior abdominal wall.

Figure 12.3 The peritoneum and associated structures. A. The peritoneal cavity (gold), the abdominal organs of the digestive system and the pelvic organs. B. The greater omentum.

The two layers of peritoneum are in close contact, and friction between them is prevented by the presence of serous fluid secreted by the peritoneal cells, thus the peritoneal cavity is only a potential cavity. A similar arrangement is seen with the membranes covering the lungs, the pleura (p. 250). In the male, the peritoneal cavity is completely closed but in the female the uterine tubes open into it and the ovaries are the only structures inside (Ch. 18).

The arrangement of the peritoneum is such that the organs are invaginated (pushed into the membrane forming a pouch) into the closed sac from below, behind and above so that they are at least partly covered by the visceral layer, and attached securely within the abdominal cavity. This means that:

• pelvic organs are covered only on their superior surface

• the stomach and intestines, deeply invaginated from behind, are almost completely surrounded by peritoneum and have a double fold (the mesentery) that attaches them to the posterior abdominal wall. The fold of peritoneum enclosing the stomach extends beyond the greater curvature of the stomach, and hangs down in front of the abdominal organs like an apron (Fig. 12.3B). This is the greater omentum, which stores fat that provides both insulation and a long-term energy store

Muscle layer

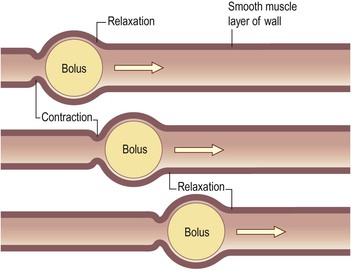

With some exceptions this consists of two layers of smooth (involuntary) muscle. The muscle fibres of the outer layer are arranged longitudinally, and those of the inner layer encircle the wall of the tube. Between these two muscle layers are blood vessels, lymph vessels and a plexus (network) of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, called the myenteric plexus (Fig. 12.2). These nerves supply the adjacent smooth muscle and blood vessels.

Contraction and relaxation of these muscle layers occurs in waves, which push the contents of the tract onwards. This type of contraction of smooth muscle is called peristalsis (Fig. 12.4) and is under the influence of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. Muscle contraction also mixes food with the digestive juices. Onward movement of the contents of the tract is controlled at various points by sphincters, which are thickened rings of circular muscle. Contraction of sphincters regulates forward movement. They also act as valves, preventing backflow in the tract. This control allows time for digestion and absorption to take place. ![]() 12.2

12.2

Submucosa

This layer consists of loose areolar connective tissue containing collagen and some elastic fibres, which binds the muscle layer to the mucosa. Within it are blood vessels and nerves, lymph vessels and varying amounts of lymphoid tissue. The blood vessels are arterioles, venules and capillaries. The nerve plexus is the submucosal plexus (Fig. 12.2), which contains sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves that supply the mucosal lining.

Mucosa

This consists of three layers of tissue:

• muscularis mucosa, a thin outer layer of smooth muscle that provides involutions of the mucosal layer, e.g. gastric glands (p. 299), villi (p. 302).

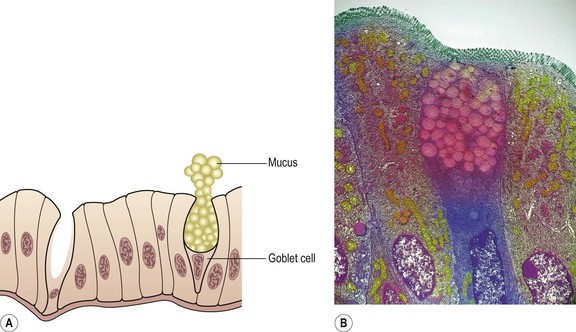

Mucous membrane

In parts of the tract that are subject to great wear and tear or mechanical injury, this layer consists of stratified squamous epithelium with mucus-secreting glands just below the surface. In areas where the food is already soft and moist and where secretion of digestive juices and absorption occur, the mucous membrane consists of columnar epithelial cells interspersed with mucus-secreting goblet cells (Fig. 12.5). Mucus lubricates the walls of the tract and provides a physical barrier that protects them from the damaging effects of digestive enzymes. Below the surface in the regions lined with columnar epithelium are collections of specialised cells, or glands, which release their secretions into the lumen of the tract. The secretions include:

• saliva from the salivary glands

• gastric juice from the gastric glands

• intestinal juice from the intestinal glands

• pancreatic juice from the pancreas

Figure 12.5 Columnar epithelium with a goblet cell. A. Diagram. B. Coloured transmission electron micrograph of a section through a goblet cell (pink and blue) of the small intestine.

These are digestive juices and most contain enzymes that chemically break down food. Under the epithelial lining are varying amounts of lymphoid tissue that provide protection against ingested microbes.

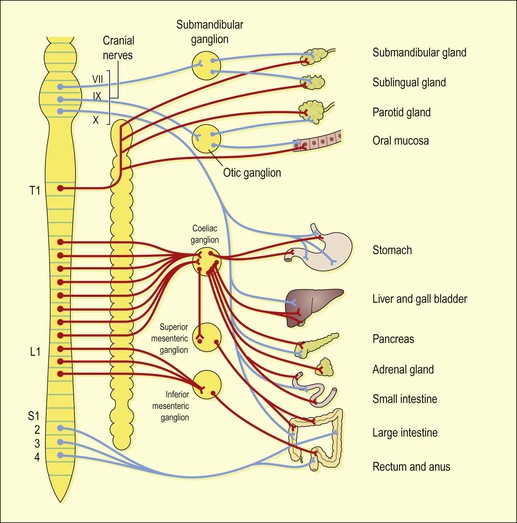

Nerve supply

The alimentary canal and its related accessory organs are supplied by nerves from both divisions of the autonomic nervous system, i.e. both parasympathetic and sympathetic parts (Fig. 12.6). Their actions are generally antagonistic to each other and at any particular time one has a greater influence than the other, according to body needs, at that time. When digestion is required, this is normally through increased activity of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Figure 12.6 Autonomic nerve supply to the digestive system. Parasympathetic – blue; sympathetic – red.

The parasympathetic supply.

One pair of cranial nerves, the vagus nerves, supplies most of the alimentary canal and the accessory organs. Sacral nerves supply the most distal part of the tract. The effects of parasympathetic stimulation on the digestive system are:

The sympathetic supply.

This is provided by numerous nerves that emerge from the spinal cord in the thoracic and lumbar regions. These form plexuses (ganglia) in the thorax, abdomen and pelvis, from which nerves pass to the organs of the alimentary tract. The effects of sympathetic stimulation on the digestive system are to:

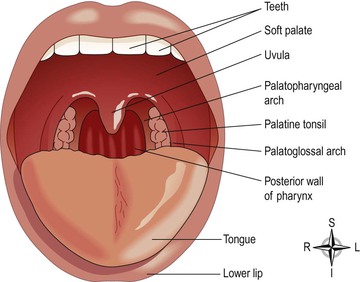

Mouth (Fig. 12.7)

The mouth or oral cavity is bounded by muscles and bones:

The oral cavity is lined throughout with mucous membrane, consisting of stratified squamous epithelium containing small mucus-secreting glands.

The part of the mouth between the gums and the cheeks is the vestibule and the remainder of its interior is the oral cavity. The mucous membrane lining of the cheeks and the lips is reflected onto the gums or alveolar ridges and is continuous with the skin of the face.

The palate forms the roof of the mouth and is divided into the anterior hard palate and the posterior soft palate (Fig. 12.1). The hard palate is formed by the maxilla and the palatine bones. The soft palate, which is muscular, curves downwards from the posterior end of the hard palate and blends with the walls of the pharynx at the sides.

The uvula is a curved fold of muscle covered with mucous membrane, hanging down from the middle of the free border of the soft palate. Originating from the upper end of the uvula are four folds of mucous membrane, two passing downwards at each side to form membranous arches. The posterior folds, one on each side, are the palatopharyngeal arches and the two anterior folds are the palatoglossal arches. On each side, between the arches, is a collection of lymphoid tissue called the palatine tonsil.

Tongue

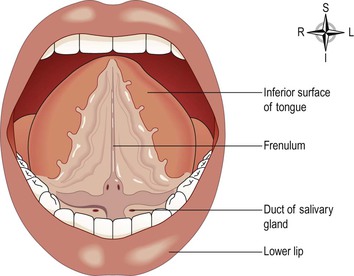

The tongue is composed of voluntary muscle. It is attached by its base to the hyoid bone (see Fig. 10.4, p. 244) and by a fold of its mucous membrane covering, called the frenulum, to the floor of the mouth (Fig. 12.8). The superior surface consists of stratified squamous epithelium, with numerous papillae (little projections). Many of these contain sensory receptors (specialised nerve endings) for the sense of taste in the taste buds (see Fig. 8.24, p. 206).

Blood supply

The main arterial blood supply to the tongue is by the lingual branch of the external carotid artery. Venous drainage is by the lingual vein, which joins the internal jugular vein.

Nerve supply

The nerves involved are:

• the hypoglossal nerves (12th cranial nerves), which supply the voluntary muscle

• the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves (7th and 9th cranial nerves), the nerves of taste.

Functions of the tongue

The tongue plays an important part in:

Nerve endings of the sense of taste are present in the papillae and widely distributed in the epithelium of the tongue.

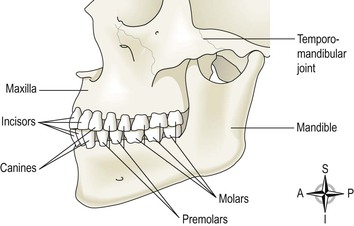

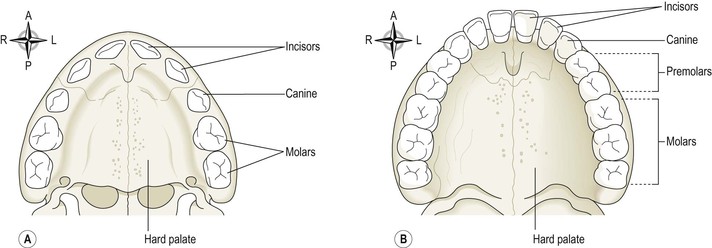

Teeth

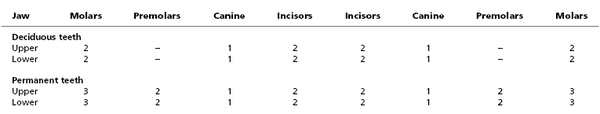

The teeth are embedded in the alveoli or sockets of the alveolar ridges of the mandible and the maxilla (Fig. 12.9). Babies are born with two sets, or dentitions, the temporary or deciduous teeth and the permanent teeth (Fig. 12.10). At birth the teeth of both dentitions are present, in immature form, in the mandible and maxilla.

Figure 12.10 The roof of the mouth. A. The deciduous teeth – viewed from below. B. The permanent teeth – viewed from below.

There are 20 temporary teeth, 10 in each jaw. They begin to erupt at about 6 months of age, and should all be present by 24 months (Table 12.1).

The permanent teeth begin to replace the deciduous teeth in the 6th year of age and this dentition, consisting of 32 teeth, is usually complete by the 21st year.

Functions of the teeth

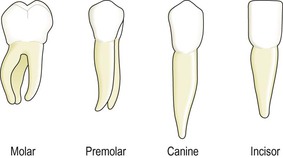

Teeth have different shapes depending on their functions. Incisors and canine teeth are the cutting teeth and are used for biting off pieces of food, whereas the premolar and molar teeth, with broad, flat surfaces, are used for grinding or chewing food (Fig. 12.11).

Structure of a tooth (Fig. 12.12)

Although the shapes of the different teeth vary, the structure is the same and consists of:

• the crown – the part that protrudes from the gum

• the root – the part embedded in the bone

• the neck – the slightly narrowed region where the crown merges with the root.

In the centre of the tooth is the pulp cavity containing blood vessels, lymph vessels and nerves, and surrounding this is a hard ivory-like substance called dentine. The dentine of the crown is covered by a thin layer of very hard substance, enamel. The root of the tooth, on the other hand, is covered with a substance resembling bone, called cementum, which secures the tooth in its socket. Blood vessels and nerves pass to the tooth through a small foramen (hole) at the apex of each root.

Blood supply

Most of the arterial blood supply to the teeth is by branches of the maxillary arteries. The venous drainage is by a number of veins which empty into the internal jugular veins.

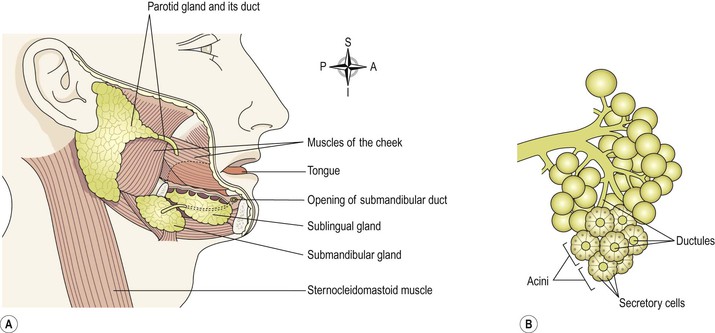

Salivary glands (Fig. 12.13)

Salivary glands release their secretions into ducts that lead to the mouth. There are three main pairs: the parotid glands, the submandibular glands and the sublingual glands. There are also numerous smaller salivary glands scattered around the mouth.

Figure 12.13 Salivary glands. A. The position of the salivary glands. B. Enlargement of part of a gland.

Parotid glands

These are situated one on each side of the face just below the external acoustic meatus (see Fig. 8.1, p. 192). Each gland has a parotid duct opening into the mouth at the level of the second upper molar tooth.

Submandibular glands

These lie one on each side of the face under the angle of the jaw. The two submandibular ducts open on the floor of the mouth, one on each side of the frenulum of the tongue.

Sublingual glands

These glands lie under the mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth in front of the submandibular glands. They have numerous small ducts that open into the floor of the mouth.

Structure of the salivary glands

The glands are all surrounded by a fibrous capsule. They consist of a number of lobules made up of small acini lined with secretory cells (Fig. 12.13B). The secretions are poured into ductules that join up to form larger ducts leading into the mouth.

Blood supply

Arterial supply is by various branches from the external carotid arteries and venous drainage is into the external jugular veins.

Composition of saliva

Saliva is the combined secretions from the salivary glands and the small mucus-secreting glands of the oral mucosa. About 1.5 litres of saliva is produced daily and it consists of:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree