Chapter 18

The reproductive systems

Ageing and the reproductive systems

Sexually transmitted infections

Diseases of the female reproductive system

Diseases of the male reproductive system

![]() Animations

Animations

18.1 Female external genitalia 450

18.2 Vestibular glands 451

18.3 Female reproductive ducts 451

18.5 Menstrual cycle 458

18.6 Ovarian cycle 458

18.9 Spermatozoa 461

18.10 Male accessory sex glands 461

18.11 Male reproductive ducts 462

18.12 Male external genitalia 462

18.13 Pathway of sperm 463

The first sections of this chapter explain the structure and functions of the female and male reproductive systems, including the production of gametes. The next sections give a brief overview of fetal development, beginning with the fusion of two gametes (fertilisation), and the effects of ageing on reproductive function. Finally, some significant reproductive disorders are described.

Female reproductive system

The functions of the female reproductive system are:

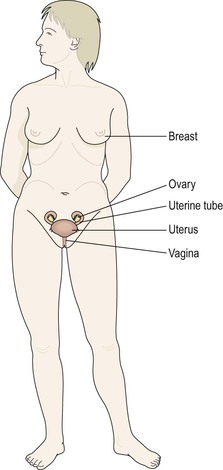

The female reproductive organs, or genitalia, include both external and internal organs (Fig. 18.1).

Figure 18.1 The female reproductive organs. Faint lines indicate the positions of the lower ribs and the pelvis.

External genitalia (vulva)  18.1

18.1

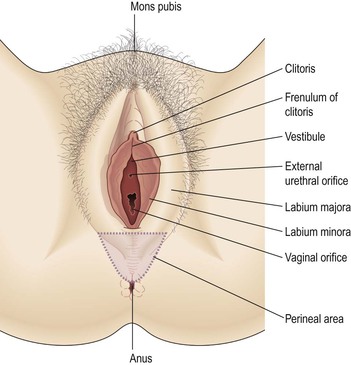

The external genitalia (Fig. 18.2) are known collectively as the vulva, and consist of the labia majora and labia minora, the clitoris, the vaginal orifice, the vestibule, the hymen and the vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands).

Labia majora

These are the two large folds forming the boundary of the vulva. They are composed of skin, fibrous tissue and fat and contain large numbers of sebaceous and eccrine sweat glands. Anteriorly the folds join in front of the symphysis pubis, and posteriorly they merge with the skin of the perineum. At puberty, hair grows on the mons pubis and on the lateral surfaces of the labia majora.

Labia minora

These are two smaller folds of skin between the labia majora, containing numerous sebaceous and eccrine sweat glands.

The cleft between the labia minora is the vestibule. The vagina, urethra and ducts of the greater vestibular glands open into the vestibule.

Clitoris

The clitoris corresponds to the penis in the male and contains sensory nerve endings and erectile tissue.

Vestibular glands  18.2

18.2

The vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands) are situated one on each side near the vaginal opening. They are about the size of a small pea and their ducts open into the vestibule immediately lateral to the attachment of the hymen. They secrete mucus that keeps the vulva moist.

Blood supply, lymph drainage and nerve supply

Arterial supply.

This is by branches from the internal pudendal arteries that branch from the internal iliac arteries and by external pudendal arteries that branch from the femoral arteries.

Venous drainage.

This forms a large plexus which eventually drains into the internal iliac veins.

Lymph drainage.

This is through the superficial inguinal nodes.

Nerve supply.

This is by branches from pudendal nerves.

Perineum

The perineum is a roughly triangular area extending from the base of the labia minora to the anal canal. It consists of connective tissue, muscle and fat. It gives attachment to the muscles of the pelvic floor (p. 427).

Internal genitalia

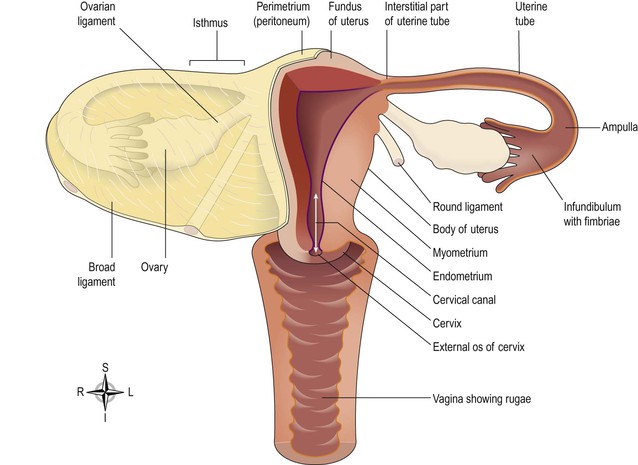

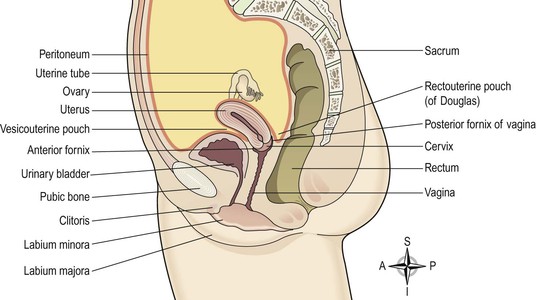

The internal organs of the female reproductive system (Figs 18.3 and 18.4) lie in the pelvic cavity and consist of the vagina, uterus, two uterine tubes and two ovaries.

Figure 18.3 Lateral view of the female reproductive organs in the pelvis and their associated structures.

Vagina  18.3

18.3

The vagina is a fibromuscular tube lined with stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 3.39) opening into the vestibule at its distal end, and with the uterine cervix protruding into its proximal end. It runs obliquely upwards and backwards at an angle of about 45° between the bladder in front and rectum and anus behind. In the adult, the anterior wall is about 7.5 cm long and the posterior wall about 9 cm long. The difference is due to the angle of insertion of the cervix through the anterior wall.

Structure of the vagina

The vaginal wall has three layers: an outer covering of areolar tissue, a middle layer of smooth muscle and an inner lining of stratified squamous epithelium that forms ridges or rugae. It has no secretory glands but the surface is kept moist by cervical secretions. Between puberty and the menopause, Lactobacillus acidophilus, bacteria that secrete lactic acid, are normally present maintaining the pH between 4.9 and 3.5. The acidity inhibits the growth of most other micro-organisms that may enter the vagina from the perineum or during sexual intercourse.

Blood supply, lymph drainage and nerve supply

Arterial supply.

An arterial plexus is formed round the vagina, derived from the uterine and vaginal arteries, which are branches of the internal iliac arteries.

Venous drainage.

A venous plexus, situated in the muscular wall, drains into the internal iliac veins.

Lymph drainage.

This is through the deep and superficial iliac glands.

Nerve supply.

This consists of parasympathetic fibres from the sacral outflow, sympathetic fibres from the lumbar outflow and somatic sensory fibres from the pudendal nerves.

Functions of the vagina

The vagina acts as the receptacle for the penis during sexual intercourse (coitus), and provides an elastic passageway through which the baby passes during childbirth.

Uterus

The uterus is a hollow muscular pear-shaped organ, flattened anteroposteriorly. It lies in the pelvic cavity between the urinary bladder and the rectum (Fig. 18.3).

In most women, it leans forward (anteversion), and is bent forward (anteflexion) almost at right angles to the vagina, so that its anterior wall rests partly against the bladder below, forming the vesicouterine pouch between the two organs.

When the body is upright, the uterus lies in an almost horizontal position. It is about 7.5 cm long, 5 cm wide and its walls are about 2.5 cm thick. It weighs between 30 and 40 grams. The parts of the uterus are the fundus, body and cervix (Fig. 18.4).

Structure

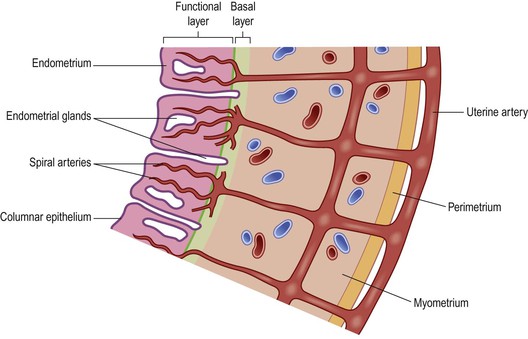

The walls of the uterus are composed of three layers of tissue: perimetrium, myometrium and endometrium (Fig. 18.5).

Figure 18.5 Layers of the uterine wall. Green line shows boundary between the functional and basal layers of the endometrium.

Perimetrium.

This is peritoneum, which is distributed differently on the various surfaces of the uterus (Fig. 18.4).

Anteriorly it lies over the fundus and the body where it is folded on to the upper surface of the urinary bladder. This fold of peritoneum forms the vesicouterine pouch.

Posteriorly the peritoneum covers the fundus, the body and the cervix, then it folds back on to the rectum to form the rectouterine pouch (of Douglas).

Laterally, only the fundus is covered because the peritoneum forms a double fold with the uterine tubes in the upper free border. This double fold is the broad ligament, which, at its lateral ends, attaches the uterus to the sides of the pelvis.

Myometrium.

This is the thickest layer of tissue in the uterine wall. It is a mass of smooth muscle fibres interlaced with areolar tissue, blood vessels and nerves.

Endometrium.

This consists of columnar epithelium covering a layer of connective tissue containing a large number of mucus-secreting tubular glands. It is richly supplied with blood by spiral arteries, branches of the uterine artery. It is divided functionally into two layers:

The upper two-thirds of the cervical canal is lined with this mucous membrane. Lower down, however, the mucosa changes, becoming stratified squamous epithelium, which is continuous with the lining of the vagina itself.

Blood supply, lymph drainage and nerve supply

Arterial supply.

This is by the uterine arteries, branches of the internal iliac arteries. They pass up the lateral aspects of the uterus between the two layers of the broad ligaments. They supply the uterus and uterine tubes and join with the ovarian arteries to supply the ovaries.

Venous drainage.

The veins follow the same route as the arteries and eventually drain into the internal iliac veins.

Lymph drainage.

Deep and superficial lymph vessels drain lymph from the uterus and the uterine tubes to the aortic lymph nodes and groups of nodes associated with the iliac blood vessels.

Nerve supply.

The nerves supplying the uterus and the uterine tubes consist of parasympathetic fibres from the sacral outflow and sympathetic fibres from the lumbar outflow.

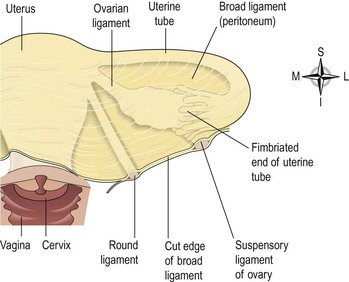

Supporting structures

The uterus is supported in the pelvic cavity by surrounding organs, muscles of the pelvic floor and ligaments that suspend it from the walls of the pelvis (Fig. 18.6).

Broad ligaments.

These are formed by a double fold of peritoneum, one on each side of the uterus. They hang down from the uterine tubes as though draped over them and at their lateral ends they are attached to the sides of the pelvis. The uterine tubes are enclosed in the upper free border and near the lateral ends they penetrate the posterior wall of the broad ligament and open into the peritoneal cavity. The ovaries are attached to the posterior wall, one on each side. Blood and lymph vessels and nerves pass to the uterus and uterine tubes between the layers of the broad ligaments.

Round ligaments.

These are bands of fibrous tissue between the two layers of broad ligament, one on each side of the uterus. They pass to the sides of the pelvis then through the inguinal canal to end by fusing with the labia majora.

Uterosacral ligaments.

These originate from the posterior walls of the cervix and vagina and extend backwards, one on each side of the rectum, to the sacrum.

Transverse cervical (cardinal) ligaments.

These extend one from each side of the cervix and vagina to the side walls of the pelvis.

Pubocervical fascia.

This extends forward from the transverse cervical ligaments on each side of the bladder and is attached to the posterior surface of the pubic bones.

Functions of the uterus

After puberty, the endometrium goes through a regular monthly cycle of changes, the menstrual cycle, under the control of hypothalamic and anterior pituitary hormones (see Ch. 9). The menstrual cycle prepares the uterus to receive, nourish and protect a fertilised ovum. The cycle is usually regular, lasting between 26 and 30 days. If the ovum is not fertilised, the functional uterine lining is shed, and a new cycle begins with a short period of vaginal bleeding (menstruation).

If the ovum is fertilised the zygote embeds itself in the uterine wall. The uterine muscle grows to accommodate the developing baby, which is called an embryo during its first 8 weeks, and a fetus for the remainder of the pregnancy. Uterine secretions nourish the ovum before it implants in the endometrium, and after implantation the rapidly expanding ball of cells is nourished by the endometrial cells themselves. This is sufficient for only the first few weeks and the placenta takes over thereafter (see Ch. 5). The placenta, which is attached to the fetus by the umbilical cord, is also firmly attached to the wall of the uterus, and provides the route by which the growing baby receives oxygen and nutrients, and gets rid of its wastes. The placenta also has an important endocrine function during pregnancy. It secretes high levels of progesterone, which prevents the muscular uterine walls from contracting in response to the progressive uterine stretching as the fetus grows. At term (the end of pregnancy) the hormone oestrogen, which increases uterine contractility, becomes the predominant sex hormone in the blood. Additionally, oxytocin is released from the posterior pituitary, and also stimulates contraction of the uterine muscle. Control of oxytocin release is by positive feedback (see also Fig. 9.5 ). During labour, the uterus forcefully expels the baby with powerful rhythmical contractions.

Uterine tubes

The uterine (Fallopian) tubes (Fig. 18.4) are about 10 cm long and extend from the sides of the uterus between the body and the fundus. They lie in the upper free border of the broad ligament and their trumpet-shaped lateral ends penetrate the posterior wall, opening into the peritoneal cavity close to the ovaries. The end of each tube has fingerlike projections called fimbriae. The longest of these is the ovarian fimbria, which is in close association with the ovary.

Structure

The uterine tubes are covered with peritoneum (broad ligament), have a middle layer of smooth muscle and are lined with ciliated epithelium. Blood and nerve supply and lymphatic drainage are as for the uterus.

Functions

The uterine tubes propel the ovum from the ovary to the uterus by peristalsis and ciliary movement. The secretions of the uterine tube nourish both ovum and spermatozoa. Fertilisation of the ovum usually takes place in the uterine tube, and the zygote is propelled into the uterus for implantation.

Ovaries  18.4

18.4

The ovaries (Fig. 18.4) are the female gonads (glands producing sex hormones and the ova), and they lie in a shallow fossa on the lateral walls of the pelvis. They are 2.5–3.5 cm long, 2 cm wide and 1 cm thick. Each is attached to the upper part of the uterus by the ovarian ligament and to the back of the broad ligament by a broad band of tissue, the mesovarium. Blood vessels and nerves pass to the ovary through the mesovarium (Fig. 18.7).

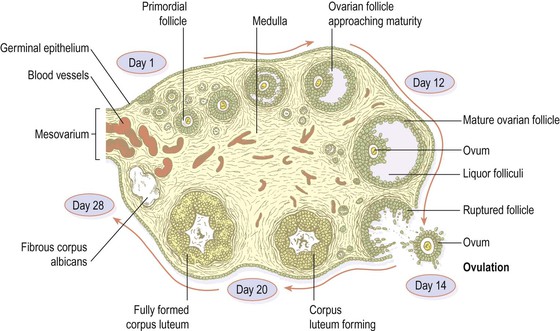

Structure

The ovaries have two layers of tissue.

Medulla.

This lies in the centre and consists of fibrous tissue, blood vessels and nerves.

Cortex.

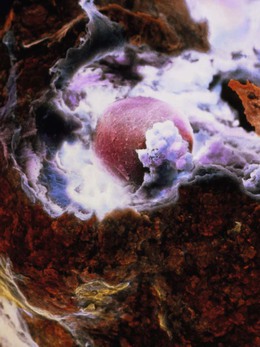

This surrounds the medulla. It has a framework of connective tissue, or stroma, covered by germinal epithelium. It contains ovarian follicles in various stages of maturity, each of which contains an ovum. Before puberty the ovaries are inactive but the stroma already contains immature (primordial) follicles, which the female has from birth. During the childbearing years, about every 28 days, one or more ovarian follicle (Graafian follicle) matures, ruptures and releases its ovum into the peritoneal cavity. This is called ovulation and it occurs during most menstrual cycles (Figs 18.7 and 18.8). Following ovulation, the ruptured follicle develops into the corpus luteum (meaning ‘yellow body’), which in turn will leave a small permanent scar of fibrous tissue called the corpus albicans (meaning ‘white body’) on the surface of the ovary.

Blood supply, lymph drainage and nerve supply

Arterial supply.

This is by the ovarian arteries, which branch from the abdominal aorta just below the renal arteries.

Venous drainage.

This is into a plexus of veins behind the uterus from which the ovarian veins arise. The right ovarian vein opens into the inferior vena cava and the left into the left renal vein.

Lymph drainage.

This is to the lateral aortic and preaortic lymph nodes. The lymph vessels follow the same route as the arteries.

Nerve supply.

The ovaries are supplied by parasympathetic nerves from the sacral outflow and sympathetic nerves from the lumbar outflow.

Functions

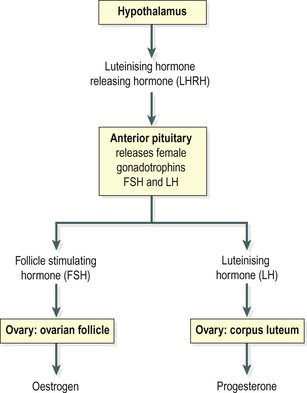

The ovary is the organ in which the female gametes are stored and develop prior to ovulation. Their maturation is controlled by the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary gland, which releases gonadotrophins (follicle stimulating hormone, FSH, and luteinising hormone, LH), both of which act on the ovary. In addition, the ovary has endocrine functions, and releases hormones essential to the physiological changes during the reproductive cycle. The source of these hormones, oestrogen, progesterone and inhibin, is the follicle itself. During the first half of the cycle, while the ovum is developing within the follicle, the follicle secretes increasing amounts of oestrogen. However, after ovulation, the corpus luteum secretes primarily progesterone, with some oestrogen and inhibin (Fig 18.9). The significance of this is discussed under the menstrual cycle (see below).

Puberty in the female

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree