The Deep Front Line

Overview

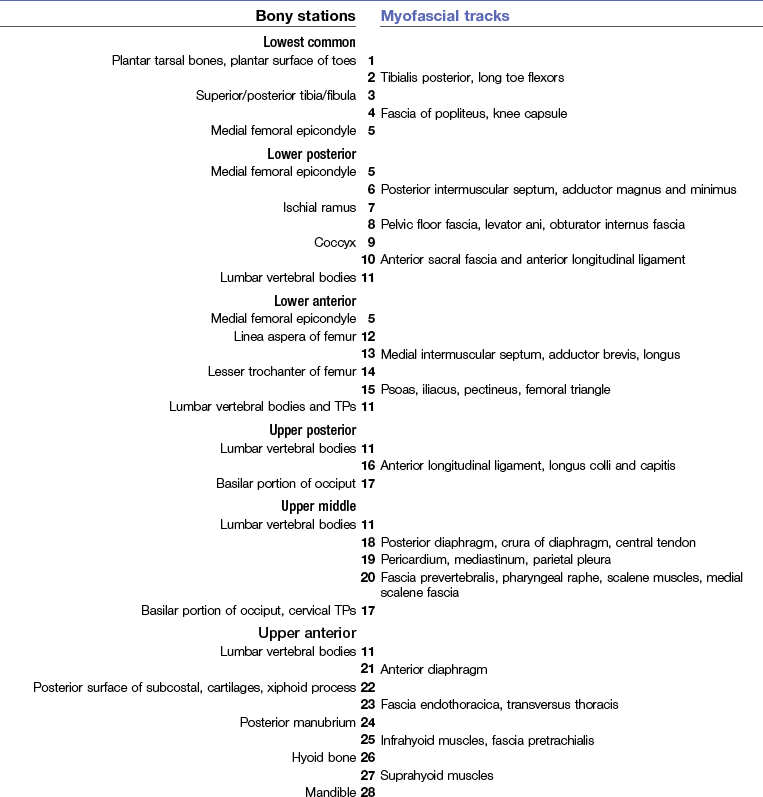

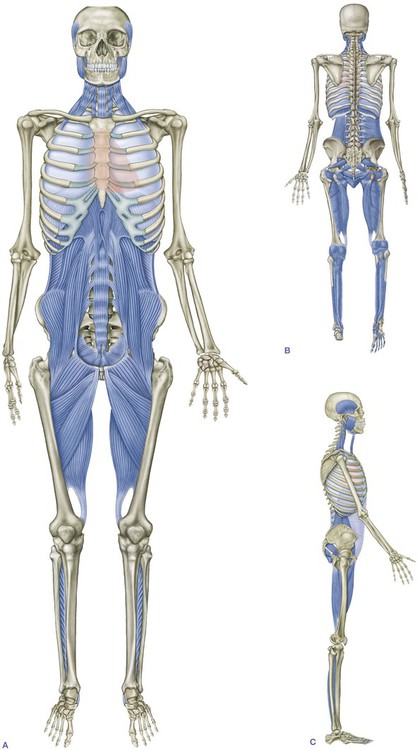

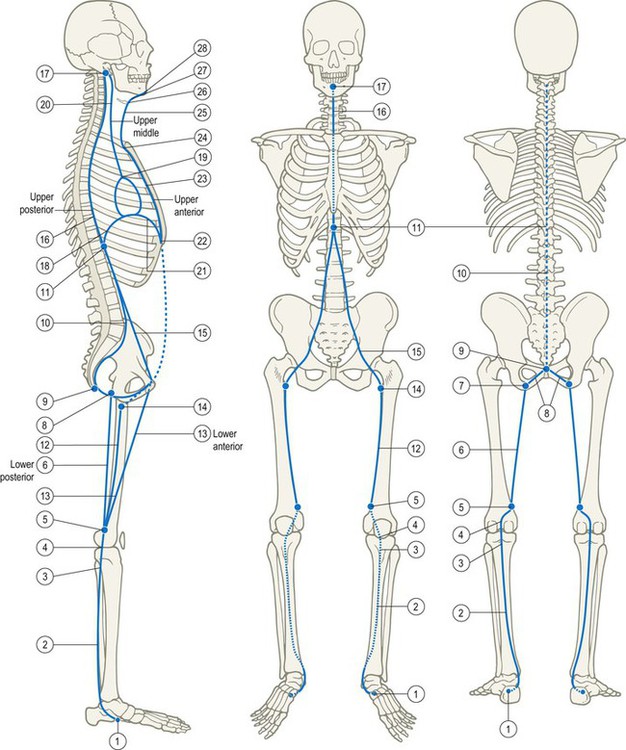

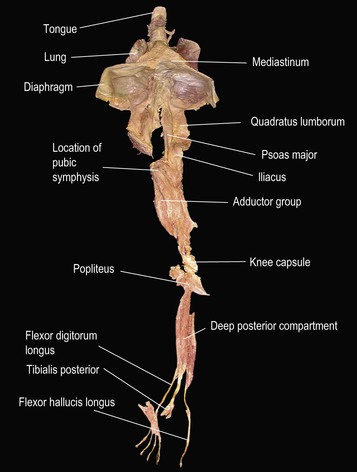

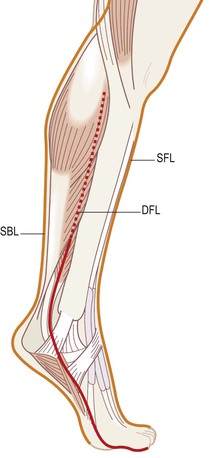

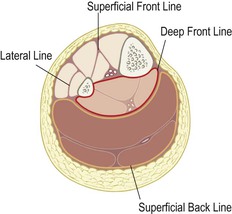

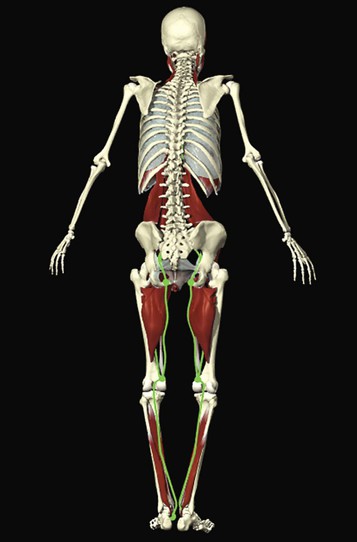

Interposed between the left and right Lateral Lines in the coronal plane, sandwiched between the Superficial Front Line (SFL) and Superficial Back Line (SBL) in the sagittal plane, and surrounded by the helical Spiral and Functional Lines, the Deep Front Line (DFL) (Fig. 9.1) comprises the body’s myofascial ‘core’. Beginning from the bottom, the line has roots deep in the underside of the foot, passing up just behind the bones of the lower leg and behind the knee to the inside of the thigh. From here the major track passes in front of the hip joint, pelvis, and lumbar spine, while an alternate track passes up the back of the thigh to the pelvic floor and rejoins the first at the lumbar spine. From the psoas–diaphragm interface, the DFL continues up through the rib cage along several alternate paths around and through the thoracic viscera, ending on the underside of both the neuro- and viscerocranium (Fig. 9.2/Table 9.1).

Compared to our other lines in previous chapters, this line demands definition as a three-dimensional space, rather than as a line. All the other lines are volumetric as well, of course, but they are more easily diagrammed as lines of pull. The DFL very clearly occupies space. Though fundamentally fascial in nature, in the leg the DFL includes many of the deeper and more obscure supporting muscles of our anatomy (Fig. 9.3). Through the pelvis, the DFL lies in intimate relation with the hip joint, and relates the wave of breathing to the rhythm of walking. In the trunk, the DFL is poised, along with the autonomic ganglia, between our neuromotor ‘chassis’ and the more ancient organs of cell support within our ventral cavity. In the neck, it provides the counterbalancing lift to the pull of both the SFL and SBL. A dimensional understanding of the DFL is necessary for successful application of nearly any method of manual or movement therapy.

Fig. 9.3 An early attempt to dissect out the Deep Front Line shows a continual tissue connection from the toes via the psoas to the tongue.

Postural function

The DFL plays a major role in the body’s support:

• stabilizing each segment of the legs, including the hip;

• supporting the lumbar spine from the front;

• surrounding and shaping the abdominopelvic balloon;

• stabilizing the chest while allowing the expansion and relaxation of breathing;

Movement function

Aside from hip adduction and the breathing wave of the diaphragm, there is no movement that is strictly the province of the DFL, yet neither is any movement outside its influence. The DFL is nearly everywhere surrounded or covered by other myofascia, which duplicate the roles performed by the muscles of the DFL. The myofascia of the DFL is infused generally with denser fascia and more slow-twitch, endurance muscle fibers, reflecting the role the DFL plays in providing stability and subtle positioning changes to the core structure to enable the more superficial structures and lines to work easily and efficiently with the skeleton. (This also applies to the DFL’s first cousins, the Deep Arm Lines; see Ch. 7.)

‘A Silken Tent’

She is as in a field a silken tent

At midday when a sunny summer breeze

Has dried the dew and all its ropes relent,

So that in guys it gently sways at ease,

And its supporting central cedar pole,

That is its pinnacle to heavenward

And signifies the sureness of the soul,

Seems to owe naught to any single cord,

But strictly held by none, is loosely bound

By countless silken ties of love and thought

To everything on earth the compass round,

And only by one’s going slightly taut

In the capriciousness of summer air

The Deep Front Line in detail

The foot and leg: the lowest common track

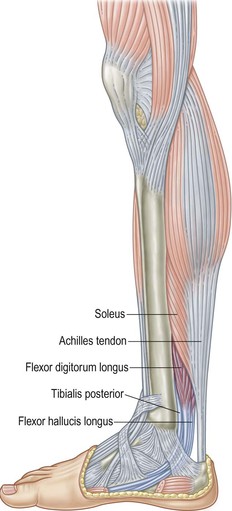

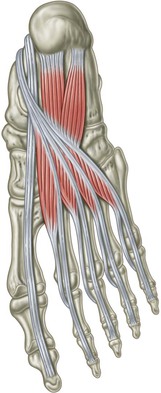

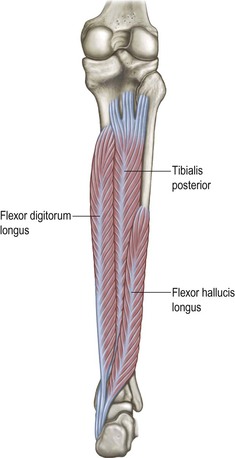

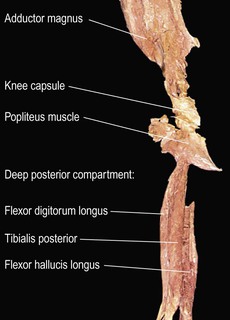

The DFL begins deep in the sole of the foot with the distal attachments of the three muscles of the deep posterior compartment of the leg: the tibialis posterior and the two long flexors of the toes, the flexor hallucis and digitorum longus (Fig. 9.4).

Fig. 9.4 The lower end of the DFL begins with the tendons of the flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus.

The tissue between the metatarsals can also be included in this line – the dorsal interossei and accompanying fascia. This connection is a little hard to justify on a fascial level except via the link between the tibialis posterior tendon and the ligamentous bed of the foot. The lumbricals clearly link fascially and functionally with the SFL, but the interossei and the space between the metatarsals both feel and react therapeutically as part of the core structure of the foot.

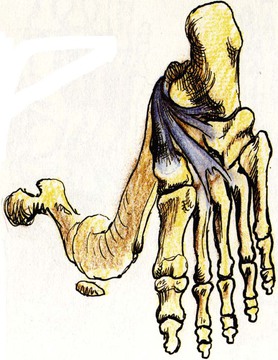

Depending on how you wield the scalpel, the tibialis posterior has multiple and variable tendinous attachments to nearly every bone in the tarsum of the foot except the talus, and to the middle three metatarsal bases besides (Fig. 9.5). This tendon resembles a hand with many fingers, reaching under the foot to support the arches and hold the tarsum of the foot together.

Fig. 9.5 Deep to the long toe flexors are the complex attachments of the tibialis posterior, also part of the DFL. (Reproduced with kind permission from Grundy 1982.)

The three major tendons pass up inside the ankle behind the medial malleolus (see Fig. 3.13). The tendon of the flexor hallucis (the tendon from the big toe) passes more posteriorly than the other two, beneath the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus and behind the talus as well. This muscle–tendon complex thus provides additional elastic recoil support to the medial arch during the push-off phase of walking (Fig. 9.6). The tendons of the two toe flexors cross in the foot, helping to ensure that toe flexion is accompanied by prehensile adduction.

Fig. 9.6 The DFL passes between the SBL and SFL tracks, contracting during the push-off phase of walking to support the medial arch.

The three join in the deep posterior compartment of the lower leg, filling in the area between the fibula and tibia behind the interosseous membrane (Fig. 9.7).

Fig. 9.7 The three muscles of the deep posterior compartment of the leg, deep to the soleus, comprise the DFL.

This line employs the last available compartment in the lower leg (Fig. 9.8). The anterior compartment serves the Superficial Front Line (Ch. 4), and the lateral peroneal compartment forms part of the Lateral Line (Ch. 5). Just above the ankle, this deep posterior compartment is completely covered by the superficial posterior compartment with the soleus and gastrocnemii of the Superficial Back Line (Ch. 3) (Fig. 9.9). Access to this compartment for manual and movement therapy is discussed below.

Fig. 9.8 The deep posterior compartment lies behind the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula. Notice that each of the fascial compartments of the lower leg ensheathes one of the Anatomy Trains lines.

General manual therapy considerations

General manual therapy considerations

Piecemeal experimentation with the myofascia of the Deep Front Line can produce mixed results. The myofascial structures of the DFL accompany the extensions of the viscera into the limbs – i.e. the neurovascular bundles – and are thus studded with endangerment sites and difficult points of entry. Practitioners familiar with working these structures will be able to make connections and apply their work in an integrated way. If these DFL structures are new to you, it is recommended that you absorb these methods from a class, where an instructor can assure your placement, engagement, and intent. With that in mind, we offer a palpation guide to structures in the DFL, but not to particular techniques in detail. References to the Anatomy Trains technique DVDs, and the website materials linked to this book where techniques are presented visually, are provided when appropriate.

Palpation guide 1: deep posterior compartment

Palpation guide 1: deep posterior compartment

![]() Although it is next to impossible to feel the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus or the tibialis posterior on the bottom of the foot, the flexor hallucis longus can be clearly felt. Extend (lift) your big toe to tighten the tendon, and it will be clearly palpable along the medial edge of the plantar fascia, under the medial arch (Fig. 9.4 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 23:46–26:18).

Although it is next to impossible to feel the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus or the tibialis posterior on the bottom of the foot, the flexor hallucis longus can be clearly felt. Extend (lift) your big toe to tighten the tendon, and it will be clearly palpable along the medial edge of the plantar fascia, under the medial arch (Fig. 9.4 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 23:46–26:18). ![]()

These three muscles are covered completely by the soleus about three inches (7 cm) above the malleolus as they pass up into the deep posterior compartment (Fig. 9.9), just behind the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula (Fig. 9.10). Reaching this myofascial compartment manually is difficult. It is possible to stretch these muscles by putting the foot into strong dorsiflexion and eversion, as in the Downward-Facing Dog pose or by putting the ball of your foot on a stair and letting the heel drop. It is, however, often difficult for either practitioner or client to discern whether the soleus (SBL) or the deeper muscles (DFL) are being stretched.

Fig. 9.10 The DFL passes behind the knee, in a deeper plane of fascia than the Superficial Back Line, with the popliteus, neurovascular bundle, and fascia on the back of the knee capsule.

It is possible to feel the state of the compartment in general by feeling through the soleus, but only if the soleus can be relaxed enough to make such palpation possible. In our experience, trying to work these muscles through the soleus is either an exercise in frustration or a way to damage the soleus by overworking it – almost literally poking holes in it – in the attempt to reach these muscles deep to it (DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 20:11–23:45).![]() An alternative way to reach this hidden layer is to insinuate your fingers close along the medial posterior edge of the tibia, separating the soleus from the tibia in order to get to the underlying (and often very tense and sore) muscles of the deep posterior compartment (Fig. 9.11 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 09:20–15:03).

An alternative way to reach this hidden layer is to insinuate your fingers close along the medial posterior edge of the tibia, separating the soleus from the tibia in order to get to the underlying (and often very tense and sore) muscles of the deep posterior compartment (Fig. 9.11 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 09:20–15:03). ![]()

Fig. 9.11 The fascia surrounding the popliteus and the posterior surface of the ligamentous capsule of the knee links the tibialis posterior to the distal end of adductor magnus at the medial femoral epicondyle.

Another hand can approach this from the outside by finding the posterior septum behind the peroneals, and ‘swimming’ your fingers into this ‘valley’ between the peroneals and the soleus on the lateral side. In this manner you have the fascial layer of the deep posterior compartment between the ‘pincers’ of your hands (Fig. 9.10 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 15:03–20:10). ![]() Couple this firmly held position with client movement, dorsi- and plantarflexion, and you can help bring mobility to these deeper tissues. Multiple repetitions may be necessary as the leg becomes progressively softer and more accessible, and movement more differentiated between the superficial and deep compartments.

Couple this firmly held position with client movement, dorsi- and plantarflexion, and you can help bring mobility to these deeper tissues. Multiple repetitions may be necessary as the leg becomes progressively softer and more accessible, and movement more differentiated between the superficial and deep compartments.

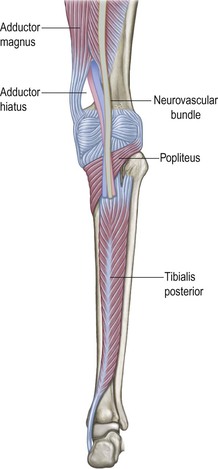

The thigh – lower posterior track

![]() At the top of the deep posterior compartment, we pass over the back of the knee with the fascia which comprises the anterior lamina of the popliteus, the neurovascular bundle of the tibial nerve and popliteal artery, and the outer layers of the strong fascial capsule which surrounds the back of the knee joint (Figs 9.10 and 9.11). The next station of this line is at the medial side of the top of the knee joint, the adductor tubercle on the medial femoral epicondyle.

At the top of the deep posterior compartment, we pass over the back of the knee with the fascia which comprises the anterior lamina of the popliteus, the neurovascular bundle of the tibial nerve and popliteal artery, and the outer layers of the strong fascial capsule which surrounds the back of the knee joint (Figs 9.10 and 9.11). The next station of this line is at the medial side of the top of the knee joint, the adductor tubercle on the medial femoral epicondyle.

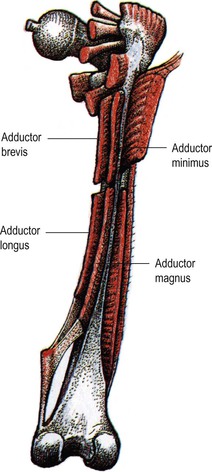

The fascia surrounding the adductors, although it is itself a unitary bag tying the adductors to the linea aspera of the femur, presents us with a switch or choice point as we move up, as the heavy fascial walls on the front and back of the adductors head off in different directions, which will not rejoin again until the lumbar spine (Fig. 9.12). We will term these two fascial continuities the lower posterior and lower anterior tracks of the DFL.

Fig. 9.12 From the medial epicondyle, two fascial planes emerge, one carrying up and forward with the adductor longus and brevis (the lower anterior track of the DFL), and another with the adductor magnus and minimus (the lower posterior track). Both ultimately surround the adductors, and both are connected to the linea aspera, but each leads to a different set of structures at the superior end. Reproduced with kind permission from Grundy 1982.

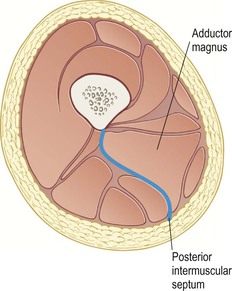

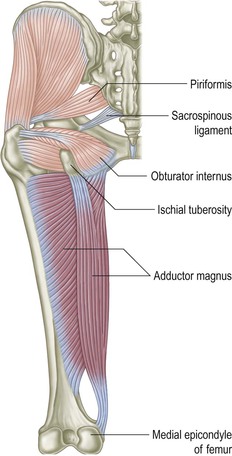

The posterior track consists of the adductor magnus muscle and the accompanying fascia between the hamstrings and the adductor group (Fig. 9.13). If we run behind the adductor group from the epicondyle, we can follow this posterior intermuscular septum up the thigh to the posterior part of the ischial ramus near the ischial tuberosity (IT), which is the attachment point of the posterior ‘head’ of adductor magnus (Fig. 9.14).

Fig. 9.13 The lower posterior track of the DFL follows the posterior intermuscular septum up the posterior aspect of the adductor magnus muscle.

Fig. 9.14 The adductor group from behind, showing the lower posterior track of the DFL up to the ischial tuberosity. This lies in the same fascial plane as the deep lateral rotators, but the transverse direction of the muscular fibers prevents us from continuing up into the buttock with this line.

From the ischium, there is a clear fascial continuity up the buttock deep to the gluteus maximus onto a group of muscles known as the deep lateral rotators (Fig. 9.15 and DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 1:23:27–1:35:54). ![]() Thus if we were going to include the deep lateral rotators in the Anatomy Trains system, they would be, strangely, part of this lower posterior track of the DFL (see also the section on the ‘Deep Back Line’, p. 95). In fact, however, even though there is a fascial connection between the posterior adductors and the quadratus femoris and the rest of the lateral rotators, the muscle fiber direction of these muscles is nearly at right angles to the ones we have been following straight up the thigh. Thus, this connection cannot qualify as a myofascial meridian by our self-imposed rules. These important muscles are best seen as part of a series of muscular fans around the hip joint, as they simply do not fit into the longitudinal meridians we are describing here (see ‘Fans of the Hip Joint’1 in Body3, published privately and available from www.anatomytrains.com).

Thus if we were going to include the deep lateral rotators in the Anatomy Trains system, they would be, strangely, part of this lower posterior track of the DFL (see also the section on the ‘Deep Back Line’, p. 95). In fact, however, even though there is a fascial connection between the posterior adductors and the quadratus femoris and the rest of the lateral rotators, the muscle fiber direction of these muscles is nearly at right angles to the ones we have been following straight up the thigh. Thus, this connection cannot qualify as a myofascial meridian by our self-imposed rules. These important muscles are best seen as part of a series of muscular fans around the hip joint, as they simply do not fit into the longitudinal meridians we are describing here (see ‘Fans of the Hip Joint’1 in Body3, published privately and available from www.anatomytrains.com).

Fig. 9.15 The deep lateral rotators, although they are crucial to the understanding and optimization of human plantigrade posture, do not fit easily into the Anatomy Trains schema. Reproduced with kind permission from Grundy 1982.

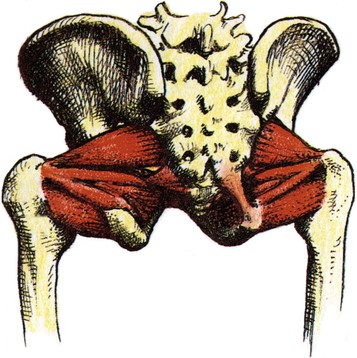

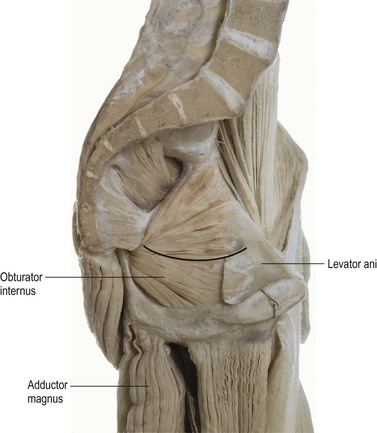

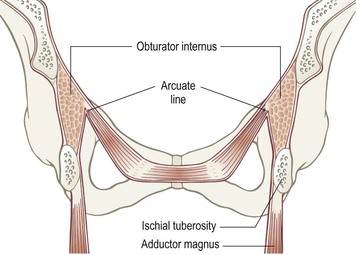

We will have an easier time finding our myofascial continuity if we run inside the lower flange of the pelvis from the adductor magnus and its septum up onto the medial side of the IT-ischial ramus (Fig. 9.16). We can follow a strong fascial connection over the bone onto the dense outer covering of the obturator internus muscle, connecting with levator ani of the pelvic floor via the arcuate line (Fig. 9.17). This is an important line of stabilization from the trunk down the inner back of the leg.

Fig. 9.16 Although the fascia has been removed in this dissection, there is a connection from the adductor magnus (and the posterior intermuscular septum represented by the dark space just behind it) across the ischial tuberosity and the lower obturator internus fascia to the arcuate line (horizontal line) where the levator ani joins the lateral wall of the true pelvis. (© Ralph T. Hutchings. Reproduced from Abrahams, et al. 1998.)

Fig. 9.17 From the posterior intermuscular septum and adductor magnus, the fascial track moves up inside the ischial tuberosity on the obturator internus fascia to contact the pelvic floor (levator ani).

The pelvic floor is a complex set of structures – a muscular funnel, surrounded by fascial sheets and visceral ligaments – worthy of several books of its own.2 For our purposes, it forms the bottom of the trunk portion of the DFL with multiple connections around the abdominopelvic cavity. We have been following the lower posterior track listed in Table 9.1. This track takes us from the coccygeus and iliococcygeus portions of the levator ani onto the coccyx, where we can continue north with the fascia on the front of the sacrum. This fascia blends into the anterior longitudinal ligament running up the front of the spine, where it rejoins the lower anterior track at the junction between the psoas and diaphragmatic crura (Fig. 9.18).

Fig. 9.18 Deep Front Line, lower posterior tracks and stations view as imaged by Primal Pictures. (Image provided courtesy of Primal Pictures, www.primalpictures.com.)

The complex sets of connections here are difficult to box into a linear presentation. We can note, for instance, that the pelvic floor, in the form of the central pubococcygeus, also connects to the posterior lamina of the rectus abdominis reaching down from above (described later in this chapter – see Fig. 9.31).

Palpation guide 2: lower posterior track

This station marks the beginning of a division between the posterior septum that runs up the back of the adductors, separating them from the hamstrings, and the anterior (medial intermuscular) septum dividing the adductors from the quadriceps. Taking the posterior septum first, place your model on his side, and find the medial femoral epicondyle (Fig. 9.14). You will find a finger’s width or more of space between this condyle and the prominent medial hamstring tendons coming from behind the knee.

Follow this valley upward as far as you can toward the IT. In some people, it will be easy to follow, and you can work your way more deeply into this septum in its ‘S’-shaped course toward the linea aspera (see Fig. 9.13). In those where the adductor magnus is ‘married’ to the hamstrings, however, the septum and surrounding tissues may be too bound to follow the valley very far into the tissue; indeed, the septum may feel instead like a piece of strapping tape between the muscles. Having the space between these muscle groups open and free is the desired state, and fingers insinuated into this division accompanied by flexion and extension of the knee can lead to freer movement between the hamstrings and posterior adductors.

To isolate the hamstrings, alternate this movement with knee flexion (leg relaxed on the table while pressing the heel against some resistance you offer with your other hand or outer thigh). The hamstrings attach to the posterior aspect of the IT; you will feel this attachment tighten in resisted knee flexion (Fig. 9.16). Place your fingers between these two structures and you will be on the upper end of the posterior adductor septum. The septum runs in a straight line between the femoral epicondyle and this upper end. In cases where the valley is impenetrable, work to spread the fascial tissues laterally and relax surrounding muscles will be rewarded with the valley appearing, and, more to the point, differentiated movement between pelvis and femur, and between hamstrings and adductor magnus (DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 43:25–44:59).![]()

The adductors themselves are amenable to general spreading work along their length (DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 36:20–42:00)![]() , and to specific work up on the medial area of the hip joint near the ischial ramus, especially for correcting a functionally short leg (DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 45:00–52:20).

, and to specific work up on the medial area of the hip joint near the ischial ramus, especially for correcting a functionally short leg (DVD ref: Deep Front Line, Part 1, 45:00–52:20). ![]()

From the adductor magnus, there is connecting fascia from the IT along its medial surface to the obturator internus fascia, and from this fascial sheet onto the pelvic floor sheets via the arcuate line (Fig. 9.18)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree