Chapter 10 The Cardiovascular Exam

A. Generalities

1 What are the main components of the cardiovascular physical examination?

The general appearance of the patient (inspection)

The general appearance of the patient (inspection)

The arterial pulse (palpation); this component also should include assessment of the arterial blood pressure (discussed separately in Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 37–127)

The arterial pulse (palpation); this component also should include assessment of the arterial blood pressure (discussed separately in Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 37–127)

The central venous pressure and the jugular venous pulse (inspection)

The central venous pressure and the jugular venous pulse (inspection)

Precordial impulses and silhouette (inspection, palpation, and percussion of the point of maximal impulse [PMI])

Precordial impulses and silhouette (inspection, palpation, and percussion of the point of maximal impulse [PMI])

B. General (Physical) Appearance

2 What aspects of general appearance should be observed in evaluating cardiac patients?

As suggested by Perloff, one should sequentially evaluate the following nine areas:

See Tables 10-1 and 10-2.

Table 10-1 Diagnostic Clues: Body and Facies, Gestures and Gait, Face and Ears

| Body Appearance and Facies |

The anasarca of congestive heart failure The anasarca of congestive heart failure |

The struggling, anguished, frightened, orthopneic, and diaphoretic look of pulmonary edema The struggling, anguished, frightened, orthopneic, and diaphoretic look of pulmonary edema |

The tall stature, long extremities (with arm span exceeding patient’s height), and sparse subcutaneous fat of Marfan’s syndrome (mitral valve prolapse, aortic dilation, and dissection) The tall stature, long extremities (with arm span exceeding patient’s height), and sparse subcutaneous fat of Marfan’s syndrome (mitral valve prolapse, aortic dilation, and dissection) |

The long extremities, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum of homocystinuria (arterial thrombosis) The long extremities, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum of homocystinuria (arterial thrombosis) |

The tall stature and long extremities of Klinefelter’s syndrome (atrial or ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and even tetralogy of Fallot) The tall stature and long extremities of Klinefelter’s syndrome (atrial or ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and even tetralogy of Fallot) |

The tall stature and thick extremities of acromegaly (hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and conduction defects) The tall stature and thick extremities of acromegaly (hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and conduction defects) |

The short stature, webbed neck, low hairline, small chin, wide-set nipples, and sexual infantilism of Turner’s syndrome (coarctation of the aorta and valvular pulmonic stenosis) The short stature, webbed neck, low hairline, small chin, wide-set nipples, and sexual infantilism of Turner’s syndrome (coarctation of the aorta and valvular pulmonic stenosis) |

The dwarfism and polydactyly of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome (atrial septal defects and common atrium) The dwarfism and polydactyly of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome (atrial septal defects and common atrium) |

The morbid obesity and somnolence of obstructive sleep apnea (hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale) The morbid obesity and somnolence of obstructive sleep apnea (hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale) |

The truncal obesity, thin extremities, moon face, and buffalo hump of hypertensive patients with Cushing’s syndrome The truncal obesity, thin extremities, moon face, and buffalo hump of hypertensive patients with Cushing’s syndrome |

The mesomorphic, overweight, balding, hairy, and tense middle-aged patient with coronary artery disease The mesomorphic, overweight, balding, hairy, and tense middle-aged patient with coronary artery disease |

The hammer toes and pes cavus of Friedreich’s ataxia (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, angina, and sick sinus syndrome) The hammer toes and pes cavus of Friedreich’s ataxia (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, angina, and sick sinus syndrome) |

The straight lower back of ankylosing spondylitis (aortic regurgitation and complete heart block) The straight lower back of ankylosing spondylitis (aortic regurgitation and complete heart block) |

| Gestures, Gait, and Stance |

The Levine’s sign (clenched fist over the chest of patients with an acute myocardial infarction) The Levine’s sign (clenched fist over the chest of patients with an acute myocardial infarction) |

The preferential squatting of tetralogy of Fallot The preferential squatting of tetralogy of Fallot |

The ataxic gait of tertiary syphilis (associated with aortic aneurysm and regurgitation) The ataxic gait of tertiary syphilis (associated with aortic aneurysm and regurgitation) |

The waddling gait, lumbar lordosis, and calves pseudohypertrophy of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a pseudo infarction pattern on ECG) The waddling gait, lumbar lordosis, and calves pseudohypertrophy of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a pseudo infarction pattern on ECG) |

| Face and Ears |

Pulsatility of the earlobes (tricuspid regurgitation) Pulsatility of the earlobes (tricuspid regurgitation) |

Head bobbing (De Musset’s and Lincoln’s signs) Head bobbing (De Musset’s and Lincoln’s signs) |

The round and chubby face of congenital pulmonary stenosis The round and chubby face of congenital pulmonary stenosis |

The hypertelorism, pigmented moles, webbed neck, and low-set ears of Turner’s syndrome The hypertelorism, pigmented moles, webbed neck, and low-set ears of Turner’s syndrome |

The round and chubby face of congenital valvular pulmonic stenosis The round and chubby face of congenital valvular pulmonic stenosis |

The elfin face (small chin, malformed teeth, wide-set eyes, patulous lips, baggy cheeks, blunt and upturned nose) of congenital stenosis of the pulmonary arteries and supravalvular aortic stenosis—often associated with hypercalcemia and mental retardation. The elfin face (small chin, malformed teeth, wide-set eyes, patulous lips, baggy cheeks, blunt and upturned nose) of congenital stenosis of the pulmonary arteries and supravalvular aortic stenosis—often associated with hypercalcemia and mental retardation. |

The unilateral lower facial weakness of infants with cardiofacial syndrome—this can be encountered in 5–10% of infants with congenital heart disease (usually ventricular septal defect); often noticeable only during crying. The unilateral lower facial weakness of infants with cardiofacial syndrome—this can be encountered in 5–10% of infants with congenital heart disease (usually ventricular septal defect); often noticeable only during crying. |

The premature aging of Werner’s syndrome and progeria (associated with premature coronary artery and systemic atherosclerotic disease) The premature aging of Werner’s syndrome and progeria (associated with premature coronary artery and systemic atherosclerotic disease) |

The drooping eyelids, expressionless face, receding hairline, and bilateral cataracts of Steinert’s disease (myotonic dystrophy, associated with conduction disorders, mitral valve prolapse) The drooping eyelids, expressionless face, receding hairline, and bilateral cataracts of Steinert’s disease (myotonic dystrophy, associated with conduction disorders, mitral valve prolapse) |

The epicanthic fold, protruding tongue, small ears, short nose, and flat bridge of Down syndrome (endocardial cushion defects) The epicanthic fold, protruding tongue, small ears, short nose, and flat bridge of Down syndrome (endocardial cushion defects) |

The dry and brittle hair, loss of lateral eyebrows, puffy eyelids, apathetic face, protruding tongue, thick and sallow skin of myxedema (associated with pericardial and coronary artery disease) The dry and brittle hair, loss of lateral eyebrows, puffy eyelids, apathetic face, protruding tongue, thick and sallow skin of myxedema (associated with pericardial and coronary artery disease) |

The macroglossia not only of Down syndrome and myxedema, but also of amyloidosis (linked to restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure) The macroglossia not only of Down syndrome and myxedema, but also of amyloidosis (linked to restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure) |

The paroxysmal facial and neck flushing of carcinoid syndrome (with pulmonic stenosis and tricuspid stenosis/regurgitation) The paroxysmal facial and neck flushing of carcinoid syndrome (with pulmonic stenosis and tricuspid stenosis/regurgitation) |

The saddle-shaped nose of polychondritis (associated with aortic aneurysm) The saddle-shaped nose of polychondritis (associated with aortic aneurysm) |

The tightening of skin and mouth, scattered telangiectasias, and hyperpigmentation/hypopigmentation of scleroderma (with pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocarditis) The tightening of skin and mouth, scattered telangiectasias, and hyperpigmentation/hypopigmentation of scleroderma (with pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocarditis) |

The flushed cheeks and cyanotic lips of mitral stenosis (acrocyanosis) The flushed cheeks and cyanotic lips of mitral stenosis (acrocyanosis) |

The gargoylism of Hurler’s syndrome (associated with mitral and/or aortic disease) The gargoylism of Hurler’s syndrome (associated with mitral and/or aortic disease) |

The short palpebral fissures, small upper lip, and hypoplastic mandible of fetal alcohol syndrome (associated with atrial or ventricular septal defects) The short palpebral fissures, small upper lip, and hypoplastic mandible of fetal alcohol syndrome (associated with atrial or ventricular septal defects) |

The diagonal earlobe crease as a (questionable) marker of coronary artery disease (earlobe sign [also known as Frank’s sign]) The diagonal earlobe crease as a (questionable) marker of coronary artery disease (earlobe sign [also known as Frank’s sign]) |

Table 10-2 Diagnostic Clues: Eyes, Extremities, Skin, Thorax, and Abdomen

| Eyes |

Xanthelasmhas of dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease (CAD) Xanthelasmhas of dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease (CAD) |

The enlarged lacrimal glands of sarcoidosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy, conduction defects, and, possibly, cor pulmonale) The enlarged lacrimal glands of sarcoidosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy, conduction defects, and, possibly, cor pulmonale) |

The cataracts and deafness of “rubella syndrome” (patent ductus arteriosus [PDA] or stenosis of the pulmonary artery) The cataracts and deafness of “rubella syndrome” (patent ductus arteriosus [PDA] or stenosis of the pulmonary artery) |

The stare and proptosis of increased central venous pressure The stare and proptosis of increased central venous pressure The lid lag, stare, and exophthalmos of hyperthyroidism (tachyarrhythmias, angina, and high output failure) The lid lag, stare, and exophthalmos of hyperthyroidism (tachyarrhythmias, angina, and high output failure) |

The conjunctival petechiae of endocarditis The conjunctival petechiae of endocarditis |

The conjunctivitis of Reiter’s disease (pericarditis, aortic regurgitation, and prolongation of the P-R interval) The conjunctivitis of Reiter’s disease (pericarditis, aortic regurgitation, and prolongation of the P-R interval) |

The blue sclerae of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) The blue sclerae of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) |

The icteric sclerae of cirrhosis The icteric sclerae of cirrhosis |

The Brushfield’s spots (small white spots on the periphery of the iris, usually crescentic and with an outward concavity, frequently but not exclusively seen in Down syndrome—endocardial cushion defects) The Brushfield’s spots (small white spots on the periphery of the iris, usually crescentic and with an outward concavity, frequently but not exclusively seen in Down syndrome—endocardial cushion defects) |

The fissuring of the iris (coloboma) of total anomalous pulmonary venous return The fissuring of the iris (coloboma) of total anomalous pulmonary venous return |

The dislocated lens of Marfan’s syndrome The dislocated lens of Marfan’s syndrome |

The retinal changes of hypertension and diabetes (CAD and congestive heart failure) The retinal changes of hypertension and diabetes (CAD and congestive heart failure) |

The Roth spots of bacterial endocarditis The Roth spots of bacterial endocarditis |

| Extremities |

The cyanosis and clubbing of “central mixing” (right-to-left shunts, pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, and drainage of the inferior vena cava into left atrium) The cyanosis and clubbing of “central mixing” (right-to-left shunts, pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, and drainage of the inferior vena cava into left atrium) |

The differential cyanosis and clubbing of PDA with pulmonary hypertension (the reversed shunt limits cyanosis and clubbing to the feet, but spares hands) The differential cyanosis and clubbing of PDA with pulmonary hypertension (the reversed shunt limits cyanosis and clubbing to the feet, but spares hands) |

The “reversed” differential cyanosis and clubbing of transposition (aorta originating from the right ventricle): hands are cyanotic and clubbed, but feet are normal The “reversed” differential cyanosis and clubbing of transposition (aorta originating from the right ventricle): hands are cyanotic and clubbed, but feet are normal |

The sudden pallor, pain, and coldness of peripheral embolization The sudden pallor, pain, and coldness of peripheral embolization |

Osler’s nodes (swollen, tender, raised, pea-sized lesion of finger pads, palms, and soles) and Janeway lesions (small, nontender, erythematous or hemorrhagic lesions of the palms or soles) of bacterial endocarditis Osler’s nodes (swollen, tender, raised, pea-sized lesion of finger pads, palms, and soles) and Janeway lesions (small, nontender, erythematous or hemorrhagic lesions of the palms or soles) of bacterial endocarditis |

The clubbing, splinter hemorrhages of endocarditis The clubbing, splinter hemorrhages of endocarditis |

The Raynaud’s of scleroderma The Raynaud’s of scleroderma |

The simian line of Down’s syndrome (atrial septal defect [ASD]) The simian line of Down’s syndrome (atrial septal defect [ASD]) |

The hyperextensible joints of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) The hyperextensible joints of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) |

The nicotine finger stains of chain smokers (CAD) The nicotine finger stains of chain smokers (CAD) |

The leg edema of congestive heart failure The leg edema of congestive heart failure |

The tightly tapered and contracted fingers of scleroderma, with ischemic ulcers and hypoplastic nails (often associated with pulmonary hypertension and myocardial disease, pericarditis, and valvulopathy) The tightly tapered and contracted fingers of scleroderma, with ischemic ulcers and hypoplastic nails (often associated with pulmonary hypertension and myocardial disease, pericarditis, and valvulopathy) |

The arachnodactyly, hyperextensible joints (especially knees, wrists, and fingers), and flat feet of Marfan’s syndrome (associated with aortic disease and regurgitation) The arachnodactyly, hyperextensible joints (especially knees, wrists, and fingers), and flat feet of Marfan’s syndrome (associated with aortic disease and regurgitation) |

The ulnar deviation of rheumatoid arthritis (pericardial, valvular, or myocardial disease) The ulnar deviation of rheumatoid arthritis (pericardial, valvular, or myocardial disease) |

The mainline track lines of addicts (tricuspid regurgitation, septic emboli, and endocarditis) The mainline track lines of addicts (tricuspid regurgitation, septic emboli, and endocarditis) |

The liver palms (thenar and hypothenar erythema) of chronic hepatic congestion The liver palms (thenar and hypothenar erythema) of chronic hepatic congestion |

| Skin |

The jaundice or hepatic congestion The jaundice or hepatic congestion |

The cyanosis of right-to-left shunt The cyanosis of right-to-left shunt |

The pallor of anemia and high output failure The pallor of anemia and high output failure |

The bronzing of hemochromatosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy) The bronzing of hemochromatosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy) |

The telangiectasias of Rendu-Osler-Weber (at times associated with pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae) The telangiectasias of Rendu-Osler-Weber (at times associated with pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae) |

The neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and axillary freckles (Crowe’s sign) of von Recklinghausen’s (pheochromocytomas) The neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and axillary freckles (Crowe’s sign) of von Recklinghausen’s (pheochromocytomas) |

The symmetric vitiligo (especially of the distal extremities) of hyperthyroidism The symmetric vitiligo (especially of the distal extremities) of hyperthyroidism |

The butterfly rash of SLE (endo-myo- pericarditis) The butterfly rash of SLE (endo-myo- pericarditis) |

The eyelid purplish discoloration of dermatomyositis (cardiomyopathy, heart block, and pericarditis) The eyelid purplish discoloration of dermatomyositis (cardiomyopathy, heart block, and pericarditis) |

The skin nodules and macules of sarcoidosis (cardiomyopathy and blocks) The skin nodules and macules of sarcoidosis (cardiomyopathy and blocks) |

The xanthomas of dyslipidemia The xanthomas of dyslipidemia |

The hyperextensible skin (and joints) of Ehlers-Danlos (mitral valve prolapse) The hyperextensible skin (and joints) of Ehlers-Danlos (mitral valve prolapse) |

The coarse and sallow skin of hypothyroidism The coarse and sallow skin of hypothyroidism |

The skin nodules (sebaceous adenomas), shagreen patches, and periungual fibromas of tuberous sclerosis (rhabdomyomas of the heart and arrhythmias) The skin nodules (sebaceous adenomas), shagreen patches, and periungual fibromas of tuberous sclerosis (rhabdomyomas of the heart and arrhythmias) |

| Thorax and Abdomen |

The thoracic bulges of ventricular septal defect/ASD The thoracic bulges of ventricular septal defect/ASD |

The pectus carinatum, pectus excavatum, and kyphoscoliosis of Marfan’s syndrome The pectus carinatum, pectus excavatum, and kyphoscoliosis of Marfan’s syndrome |

The akyphotic and straight back of mitral valve prolapse The akyphotic and straight back of mitral valve prolapse |

The systolic (and rarely diastolic) murmurs of pectus carinatum, excavatum, straight back The systolic (and rarely diastolic) murmurs of pectus carinatum, excavatum, straight back |

The barrel chest of emphysema (cor pulmonale) The barrel chest of emphysema (cor pulmonale) |

The shield chest of Turner’s syndrome The shield chest of Turner’s syndrome |

The cor pulmonale of severe kyphoscoliosis The cor pulmonale of severe kyphoscoliosis |

The ascites of right-sided or biventricular failure The ascites of right-sided or biventricular failure |

The hepatic pulsation of tricuspid regurgitation The hepatic pulsation of tricuspid regurgitation |

The positive abdominojugular reflux of congestive heart failure The positive abdominojugular reflux of congestive heart failure |

C. The Arterial Pulse

3 Which arteries should be examined during the evaluation of the arterial pulse?

Arteries on both sides should be compared to detect asymmetries suggestive of embolic, thrombotic, atherosclerotic, dissecting, or extrinsic occlusion.

Arteries on both sides should be compared to detect asymmetries suggestive of embolic, thrombotic, atherosclerotic, dissecting, or extrinsic occlusion.

Arteries of upper and lower extremities should be simultaneously examined in hypertensive patients to identify reduction in volume (or pulse delays) suggestive of aortic coarctation.

Arteries of upper and lower extremities should be simultaneously examined in hypertensive patients to identify reduction in volume (or pulse delays) suggestive of aortic coarctation.

If trying to evaluate the characteristics of the arterial waveform, you should examine only central arteries—carotid, brachial, or femoral.

If trying to evaluate the characteristics of the arterial waveform, you should examine only central arteries—carotid, brachial, or femoral.

Since this section focuses on the bedside examination of the arterial wave as part of the cardiovascular exam, we will exclusively discuss evaluation of central arteries. Assessment of peripheral vessels is discussed in Chapter 22, Extremities and Peripheral Vascular Exam, questions 1–25.

5 What alterations occur in peripheral arteries?

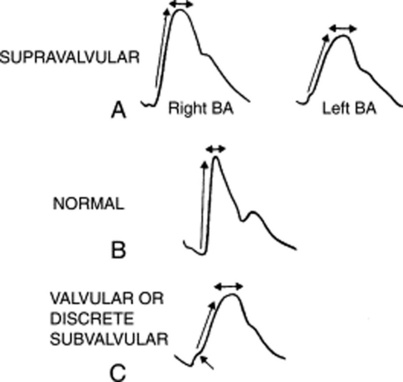

The major ones are an increase in amplitude and upstroke velocity. As the distance from the aortic valve increases, the primary percussion wave that is transmitted downward along the aorta begins to merge with the secondary waves that reverberate back from more peripheral arteries. This fusion leads to greater amplitude and upstroke velocity in peripheral as compared to central arteries (Fig. 10-1). This phenomenon is similar to that occurring at the shoreline, where waves tend to be taller. It is also the mechanism behind Hill’s sign, the higher indirect systolic pressure of lower extremities as compared to upper extremities (see Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 110–115).

12 What are the characteristics of a normal arterial pulse?

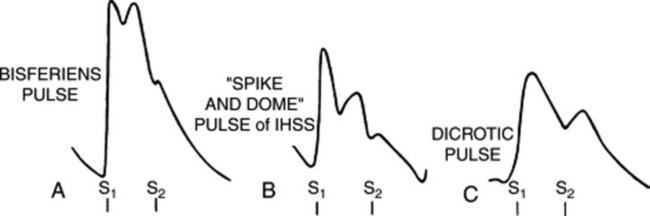

A normal arterial pulse comprises a primary (systolic) and a secondary (diastolic) wave. These are separated by a dicrotic notch (dikrotos, double-beating in Greek), which corresponds to the closure of the semilunar valves (S2) (see Fig. 10-2).

14 How are primary and secondary waves generated?

The primary wave derives from the ejection of blood into the aorta. Its early portion (percussion wave) reflects discharge into the central aorta, whereas its mid-to-late portion (tidal wave) reflects movement of blood from the central to the peripheral aorta. The two portions are separated by an anacrotic notch, only visible on tracing and usually not palpable.

The primary wave derives from the ejection of blood into the aorta. Its early portion (percussion wave) reflects discharge into the central aorta, whereas its mid-to-late portion (tidal wave) reflects movement of blood from the central to the peripheral aorta. The two portions are separated by an anacrotic notch, only visible on tracing and usually not palpable.

The secondary wave is generated instead by the elastic back-reflection of the waveform, from the peripheral arteries of the lower half of the body.

The secondary wave is generated instead by the elastic back-reflection of the waveform, from the peripheral arteries of the lower half of the body.

18 How can you differentiate supravalvular from valvular aortic stenosis?

Supravalvular AS is associated with right-to-left asymmetry of the arterial pulse: the right brachial is normal while the left resembles the pulse of valvular AS (see Fig. 10-3). This is akin to aortic coarctation and underscores the importance of examining both pulses.

20 What is the significance of a brisk arterial upstroke?

The simultaneous emptying of the left ventricle into a high-pressure bed (the aorta) and a lower pressure bed. The latter can be the right ventricle (in patients with ventricular septal defect, VSD) or the left atrium (in patients with mitral regurgitation, MR). Both will allow a rapid left ventricular emptying, which, in turn, generates a brisk arterial upstroke. The pulse pressure, however, remains normal.

The simultaneous emptying of the left ventricle into a high-pressure bed (the aorta) and a lower pressure bed. The latter can be the right ventricle (in patients with ventricular septal defect, VSD) or the left atrium (in patients with mitral regurgitation, MR). Both will allow a rapid left ventricular emptying, which, in turn, generates a brisk arterial upstroke. The pulse pressure, however, remains normal.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Despite its association with left ventricular obstruction, this disease is characterized by a brisk and bifid pulse, due to the hypertrophic ventricle and its delayed obstruction.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Despite its association with left ventricular obstruction, this disease is characterized by a brisk and bifid pulse, due to the hypertrophic ventricle and its delayed obstruction.

22 What is pulsus paradoxus?

It is an exaggerated fall in systolic blood pressure during quiet inspiration. In contrast to evaluation of arterial contour and amplitude, pulsus paradoxus is best detected in a peripheral vessel, such as the radial. Although palpable at times, optimal detection of the pulsus paradoxus usually requires a sphygmomanometer (see Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 85–103).

30 What is a double-peaked pulse?

It is a pulse characterized by two palpable spikes per cycle (Fig. 10-4). The first peak always occurs in systole, whereas the second may instead occur during either systole (as part of the primary wave: pulsus bisferiens and bifid pulse) or diastole (as part of the secondary wave: dicrotic pulse).

33 What is the diagnostic significance of a pulsus bisferiens?

Double Korotkoff sound: This is heard during measurement of systolic blood pressure, with the cuff being slowly deflated. It coincides with the systolic arterial peak.

Double Korotkoff sound: This is heard during measurement of systolic blood pressure, with the cuff being slowly deflated. It coincides with the systolic arterial peak.

Traube’s femoral sound(s): Reported by Traube in 1867, this is a loud, explosive, and shot-like systolic sound heard over a large central artery (femoral usually, but also brachial or carotid) in synchrony with the arterial pulse. It is detected whenever light pressure is applied with the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the artery, coupled with mild arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head. Although more often single (and thus called pistol shot sound), it can also be double (hence, referred to as Traube’s femoral double sounds) and sometimes even triple. It reflects the sudden systolic distention of the arterial wall—like a sail filling with wind. A single shot occurs in approximately one half of all AR patients, but may also take place in other high output states. Double sounds occur in one fourth of AR patients. Lack of arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head sharply decreases the test’s sensitivity, confining it to cases with severe left ventricular dilation. Like the water hammer pulse, Traube’s sound(s) has 37–55% sensitivity for AR and 63–98% specificity.

Traube’s femoral sound(s): Reported by Traube in 1867, this is a loud, explosive, and shot-like systolic sound heard over a large central artery (femoral usually, but also brachial or carotid) in synchrony with the arterial pulse. It is detected whenever light pressure is applied with the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the artery, coupled with mild arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head. Although more often single (and thus called pistol shot sound), it can also be double (hence, referred to as Traube’s femoral double sounds) and sometimes even triple. It reflects the sudden systolic distention of the arterial wall—like a sail filling with wind. A single shot occurs in approximately one half of all AR patients, but may also take place in other high output states. Double sounds occur in one fourth of AR patients. Lack of arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head sharply decreases the test’s sensitivity, confining it to cases with severe left ventricular dilation. Like the water hammer pulse, Traube’s sound(s) has 37–55% sensitivity for AR and 63–98% specificity.

38 What is the prognostic value of a pulsus bisferiens?

It indicates a very large stroke volume. Hence, it may disappear with left ventricular dysfunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree