Chapter Twenty-Two. The accessory digestive organs

Introduction

The alimentary system contains not only the gastrointestinal tract discussed in Chapter 21 but also the associated and accessory organs for digestion. It is an artificial division to separate out these accessory organs, as their function is integrated into the system. However, the sheer complexity of the physiology may be better understood by this format. This chapter discusses the contribution of the salivary glands, the pancreas and the liver to the process of digestion. The role of the liver in detoxification of drugs and ingested substances and the limitations to the protective role of the placenta are also discussed. Readers are referred to the selection of referenced textbooks if more detailed information is required.

The salivary glands

Three pairs of salivary glands produce the saliva that aids speech, chewing and swallowing. They are the parotid, submaxillary and sublingual glands. The parotid glands are the largest pair and are situated by the angle of the jaw. These glands produce a watery solution forming 25% of the daily saliva secretion. The submaxillary glands lie below the upper jaw and produce thicker saliva which forms 70% of the total daily output. The sublingual glands lie under the tongue on the floor of the mouth and produce only 5% of the daily output. Their solution is rich in glycoproteins, called mucins, which are primarily responsible for the lubricating action of saliva. Salivary glands produce 1–1.5 L of saliva each day. Saliva consists of 99.5% water and 0.5% solutes and has a pH value around 7.0.

The functions of saliva

• It cleanses the mouth. It contains lysozyme, which has an antiseptic action and the immunoglobulin IgA as a defence against micro-organisms.

• It provides oral comfort, reducing friction and allowing speech.

• It facilitates the formation of a bolus of partly broken up food ready to swallow. The mucins present in saliva help to mould and lubricate the bolus.

• It contains a digestive enzyme, salivary or α-amylase (formerly know as ptyalin), which acts upon starch to convert polysaccharides into disaccharides.

Control of saliva production

The secretion of saliva is controlled primarily by parasympathetic supply from the facial (VII cranial) nerve and the glossopharyngeal (IX cranial) nerve. Normally, parasympathetic stimulation produces continuous moderate watery amounts of saliva while sympathetic activity produces a sparse viscid secretion and the dry mouth most of us experience during times of stress or following the administration of atropine or hyoscine, which block receptor sites for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

Saliva is produced as a conditioned reflex in response to the cerebral perception of the thought, sight or smell of food. The salivary nuclei are situated in the reticular formation in the floor of the fourth ventricle and, when stimulated by the thought, sight or smell of food, secretion of saliva occurs. The presence of food in the mouth will also lead to saliva production—an unconditioned reflex where the impulse created by the physical presence of the food in the mouth directly stimulates the salivary nuclei without the cerebral cortex being involved. The process of deglutition propels the food into the stomach and the next stage in the digestion of food can continue.

The pancreas

The pancreas is a gland lying just below the stomach that has both endocrine and exocrine functions. It is a soft friable pink gland, is ‘tadpole’-shaped, with a head surrounded by the C-shaped loop of the duodenum and a tail which extends towards the right side of the abdomen. Most of the pancreas is retroperitoneal. Through the centre of the pancreas runs the pancreatic duct, which fuses with the common bile duct just before it enters the duodenum at the hepatopancreatic ampulla.

Exocrine functions of the pancreas

Within the pancreas are the acini, which are clusters of cells surrounding small ducts. These provide the exocrine function and play a major role in digestion. The cells form and store zygomen granules, consisting of a wide range of digestive enzymes that act on all nutrients. The enzymes are secreted into the pancreatic duct and then into the duodenum.

Pancreatic juice

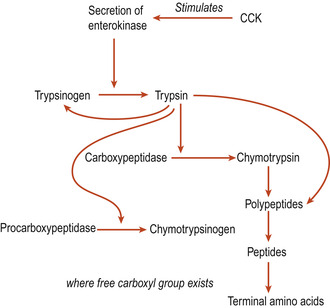

The pancreatic enzymes were briefly mentioned in Chapter 21. About 1.5–2 L of pancreatic juice are secreted daily with a pH of 8–8.4. A mixture of two types of secretions are produced: a copious watery solution and a scanty solution rich in enzymes. The profuse watery solution contains the ions hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate), sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, sulphate, phosphate and some albumin and globulin proteins. The enzyme-rich secretion contains the three proteolytic enzymes trypsinogen, trypsin and carboxypeptidase. Enzyme activity is summarised in Figure 22.1. Other enzymes are pancreatic amylase, pancreatic lipase, ribonuclease and deoxyribonuclease.

|

| Figure 22.1 Summary of activity of the pancreatic proteolytic enzymes. (From Hinchliff S M, Montague S E 1990, with permission.) |

Control of pancreatic juice secretion

The hormones secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK) were mentioned in Chapter 21. Secretin is produced by the S cells in the duodenum and upper jejunum, when acid chyme enters the duodenum. This enters the venous systemic circulation and arrives back at the pancreas via the pancreatic artery. Its presence results in the secretion of the watery component, which is rich in bicarbonate but low in enzymes.

Cholecystokinin secreted by the columnar cells of the duodenum and jejunum in response to the presence of the products of protein and fat digestion, also circulates and returns to the pancreas via the pancreatic artery. Its presence causes the release of the enzyme-rich secretion. CCK has many important functions:

• Stimulation of the enzyme-rich pancreatic secretion.

• The slowing of gastric emptying and inhibition of gastric secretion.

• Stimulation of the secretion of enterokinase.

• Stimulation of glucagon secretion.

• Stimulation of motility of the small intestine and colon.

• Contraction of the gall bladder with the release of bile.

Endocrine functions of the pancreas

Scattered among the acinar cells are approximately a million pancreatic islets (also called islets of Langerhans), which are tiny cell clusters that make up 1% of the pancreas and produce pancreatic hormones (Marieb & Hoehn 2008). There are two types of cells: the α cells synthesise glucagon, and a more numerous population of cells; the β cells, produce insulin. The normal human pancreas produces about 40 international units (IU) of insulin in 24 h. The other cells produce somatostatin, which acts to suppress islet cell hormone production. A hormone called amylin appears to be an insulin antagonist.

Glucagon

Glucagon is a short polypeptide of 29 amino acids and a potent hyperglycaemic agent. One molecule of glucagon causes the release of 100 million molecules of glucose into the blood (Marieb & Hoehn 2008). Glucagon acts mainly in the liver to promote:

• Glycogenolysis (the breakdown of glycogen to glucose).

• Lipolysis.

• Gluconeogenesis (the formation of glucose from fatty acids and amino acids).

The liver releases the glucose into the bloodstream, raising the blood sugar level. There is a fall in serum amino acid levels as the liver then takes up amino acids to synthesise new glucose molecules.

Falling blood sugar levels stimulate secretion of glucagon from α cells. Increasing amino acid levels also stimulates glucagon release. Glucagon release is suppressed by increasing blood sugar levels and by somatostatin.

Insulin

Insulin is also a small polypeptide consisting of 51 amino acids. It begins as the middle part of a larger polypeptide chain called proinsulin. Enzymes cut amino acid bonds to release the functional hormone just before the insulin is secreted from the β cell. Insulin affects the metabolism of fat and protein as well as of glucose (Table 22.1).

| On glucose | On fat | On protein | On electrolytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulates glucose utilisation Stimulates glycogen synthesis Inhibits glycogen breakdown Inhibits gluconeogenesis | Stimulates fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis Inhibits triglyceride breakdown | Stimulates incorporation of amino acids into protein molecules | Stimulates the entry of potassium into cells |

Production of insulin

Insulin production is stimulated by glucose, amino acids and fatty acids in blood and hyperglycaemic agents such as glucagon, adrenaline (epinephrine), growth hormone, thyroxine and glucocorticoids. Insulin production is inhibited by somatostatin. Insulin binds firmly to a receptor site on the cell membrane. It appears to modify cellular activity without entering the cell. The presence of calcium is necessary for its functioning. A high-carbohydrate diet leads to increased sensitivity of tissues to insulin and this may be due to a rise in the number of insulin receptors in the cell walls.

The role of insulin at cellular level

Insulin assists the entry of glucose into muscle cells, connective tissue cells and white blood cells. It does not facilitate entry of glucose into liver, kidney and brain cells. Those cells have easy access to glucose regardless of insulin (Marieb & Hoehn 2008). Insulin counters any metabolic activity that would increase plasma glucose levels such as glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. These last effects are probably due to insulin inhibition of glucagon. Once glucose has entered the cells, insulin triggers enzyme activity which:

• Catalyses the oxidation of glucose to produce ATP.

• Joins glucose molecules together to form glycogen.

• Converts glucose to fat, particularly in adipose tissue.

These processes are considered in more detail in Chapter 23.

The liver and gall bladder

The liver, which is one of the accessory organs and is associated with the small intestine, is one of the body’s most important organs. While it has many metabolic roles (see Ch. 23), its only digestive function is to secrete bile, which it stores in the gall bladder and discharges into the duodenum. Bile acts on fats to emulsify them; i.e. to break fat up into tiny particles so that it is more accessible to digestive enzymes.

Anatomy

The liver is a very large gland and weighs on average 1.4 kg. It is located in the abdominal cavity under the diaphragm, extending more to the right of the midline than the left, obscuring the stomach (Fig. 22.2). It lies totally protected by the rib cage (Fig. 22.3). The liver has four lobes (Fig. 22.4):

1. The right lobe, which is the largest.

2. The smaller left lobe.

3. The caudate lobe, which is the posterior lobe.

4. The quadrate lobe, which lies inferior to the left lobe.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree