84

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH AN ALCOHOL USE DISORDER

■ PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH AN OPIOID USE DISORDER

■ PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH BENZODIAZEPINE USE DISORDER

■ PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH NICOTINE USE DISORDER

■ PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH STIMULANT USE DISORDER

■ ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION IN PATIENTS WITH ADDICTIONS

Surgery may be required for complications of drug and alcohol use such as the management of traumatic injuries, infections of the skin, soft tissue, bones, and joints, infective endocarditis, and certain cancers. Because of the high prevalence of substance use, patients who use substances will be among those who are planning to undergo surgery that is unrelated to drug and alcohol use complications. Substance use and its associated chronic medical conditions can increase the risk of postoperative complications. In a retrospective study of patients presenting with traumatic mandibular fractures in which two-thirds reported of current or past alcohol or drug use disorder, postoperative complications including wound infections and poor healing were up to five times more likely in groups with substance use disorder compared to nonusers (1). Hospitalization for surgery may be the first time that an addicted patient does not have access to alcohol or other drugs, putting him or her at risk for withdrawal. Acute withdrawal syndromes may complicate surgery and the postoperative course by presenting as tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, delirium, pain, and seizures. Therefore, providers of perioperative care must identify addiction disorders and be comfortable with the management of substance withdrawal syndromes. The care of patients with addiction disorders is also complicated by a potential mutual distrust that exists between patients and their medical team, with physician fear of being deceived and patient fear of being mistreated and stigmatized (2). Often, preoperative evaluations can be deceivingly simple in this patient population because they are often without known chronic illnesses. However, careful evaluation may detect clinical signs of chronic diseases secondary to alcohol or drug use that increase surgical risk, such as diseases affecting the heart, lungs, kidney, liver, nervous system, and pancreas. In addition, the physiologic stress associated with surgery may bring out subclinical comorbidities not obvious during routine preoperative evaluation. Treating physicians should not expect to cure the patient’s alcohol or drug problem during the hospitalization, but should focus on getting the patient through the perioperative period safely and then offering the patient referral to long-term addiction treatment. This chapter focuses on relevant perioperative issues in the alcohol- or drug-using patient.

PERIOPERATIVE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH AN ALCOHOL USE DISORDER

Unhealthy alcohol use is common especially in patients seeking medical and surgical care (3). The prevalence of alcohol use disorders is as high as 40% in emergency room and various surgical inpatient settings and up to 50% in patients with trauma (4). Many chronic medical conditions that can complicate or necessitate surgery, including dilated cardiomyopathy, cirrhosis, pancreatitis, and oral and esophageal cancers, are attributable to alcohol. The incidence of symptomatic alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients is as high as 8% and is two to five times higher in hospitalized trauma and surgical patients (5–7). Chronic alcohol use can increase the risk of postoperative complications through immune suppression, reduced cardiac function, and dysregulated homeostasis including alterations in platelet production, aggregation, and changes in fibrinogen levels (5,8,9). Postoperative complications appear to show a dose–response relationship with alcohol consumption, that is, the more alcohol consumed, the higher risk for postoperative complications (10). Therefore, preoperative screening for unhealthy alcohol use and withdrawal risk is important.

Preoperative Evaluation

In addition to a complete history and physical examination, the preoperative evaluation should assess for the risk of acute alcohol withdrawal and the presence of diseases associated with heavy alcohol use. Physicians often fail to identify alcohol use disorders in medical patients (11). In one study, only 16% of people with alcoholism were identified in the perioperative setting (12). The amount of alcohol consumed is a risk factor for hospital admission (13) and postoperative complications (14). When screening for alcohol use disorders, it is important to remember that patients with unhealthy alcohol use are often asymptomatic and often minimize consumption. Quantity and frequency questions are essential, but are generally not sensitive or specific, with the exception of specific items that have been validated for this purpose. Laboratory tests such as blood alcohol levels and liver function tests are not sensitive or specific. Adults undergoing preoperative evaluation should be screened using validated questionnaires such as the CAGE, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), the AUDIT-C, or a single-item screening question. The 3-item AUDIT-C can identify patients at risk for postoperative complications but also for increased postoperative health care utilization (i.e., hospital length of stay, more ICU days, and increased probability to return to the operating room) (15,16).

The CAGE (17) questionnaire is brief and memorizable; however, it is designed to detect alcohol use disorders and focuses on the consequences of drinking and may remain positive in patients who are in recovery. The CAGE mnemonic refers the following questions: Have you ever felt you should Cut down on your drinking? Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about drinking? Have you ever taken a drink first thing in the morning (Eye-opener) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? Two or more positive replies to the CAGE questionnaire have a sensitivity of 74% to 78% and specificity of 76% to 96% and are therefore highly suggestive of an alcohol use disorder (18,19).

Other historical findings suggestive of unhealthy alcohol use include a history of traumatic injuries, marital, social and legal problems, homelessness, and a history of withdrawal and blackout episodes (20). Screening preoperatively in the surgical setting differs from screening in other settings. In the surgical setting, screening for risk of withdrawal and medical comorbidities are the priorities. Consider including one or more of the following questions regarding alcohol withdrawal in the preoperative evaluation:

■ Have you ever gone through alcohol withdrawal, such as having the shakes?

■ Have you ever had problems or gotten sick when you stopped drinking?

■ Have you ever had a seizure or delirium tremens, been confused, after cutting down or stopping drinking?

The spectrum of withdrawal ranges from mild tremor, hallucinosis, to seizures and delirium tremens. In the postoperative period, withdrawal can mimic many postoperative complications including acute pain and sepsis. The incidence of alcohol withdrawal is two to five times higher in hospitalized trauma and surgical patients (5,6). Risk factors associated with severe and prolonged alcohol withdrawal include amount and duration of alcohol use, prior withdrawal episodes, recurrent detoxifications, older age, and comorbid diseases (21). It is also important to note that sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines) and analgesics (e.g., opioids) given during surgery and the postoperative period may delay, partially treat, or obscure some symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. It is important to assess for other drug use as well, because many patients with unhealthy alcohol use other substances such as benzodiazepines and cocaine. Physical examination should evaluate for evidence of liver, pancreatic, nervous system, and cardiac disease. The spectrum of alcoholic liver disease ranges from fatty liver with normal or mild elevations in liver function tests to acute hepatitis and cirrhosis. Clinical evidence of cirrhosis including jaundice, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, spider telangiectases, as well as findings consistent with portal vein hypertension, namely splenomegaly, ascites, hemorrhoids, and caput medusa (dilation of the peri-umbilical veins on the abdominal wall), should be looked for. Pancreatitis can present as acute and chronic abdominal pain as well as exocrine (i.e., malabsorption) and endocrine dysfunction (i.e., glucose intolerance to diabetes mellitus). Pancreatic calcifications seen on abdominal imaging studies are another clue to chronic pancreatitis. Alcohol-associated dementia occurs in approximately 9% of people with alcoholism (22). Korsakoff syndrome, hepatic and Wernicke encephalopathy, myelopathies, and polyneuropathies are other nervous system disorders associated with long-term regular heavy alcohol use. These neurologic conditions can worsen during the perioperative period and may be confused with other postoperative neurologic complications. Therefore, preoperative baseline mental status and cognition should be assessed and documented. Preoperative evaluation for congestive heart failure should be considered because up to one-third of patients with long-standing heavy alcohol use have a decreased cardiac ejection fraction (23). Because of the association between heavy alcohol use/ alcohol use disorders and nicotine use disorder, smoking-related comorbidities such as coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) should also be evaluated for. Up to 20% of alcohol-dependent patients were found to suffer from COPD in one series (24). Preoperative laboratory studies should include electrolytes, liver function and synthetic tests, coagulation studies, and a complete blood count. Anemia is common in patients with alcohol use disorders as well as decreased platelet count from alcohol- associated bone marrow suppression and splenic sequestration. Preexisting anemia may need to be treated preoperatively because these patients are at increased risk of perioperative bleeding secondary to coagulopathies and thrombocytopenia (25). It is also important to identify patients who are in recovery preoperatively because they may have concerns and questions about perioperative exposure to sedative hypnotics and opioid analgesics.

Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

One of the most common complications of hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder is withdrawal, with up to 15% at risk for developing seizures or delirium tremens (26). The spectrum of alcohol withdrawal ranges from minor symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity including diaphoresis, tachycardia, systolic hypertension to tremor, insomnia, hallucinations, nausea, vomiting, psychomotor agitation, anxiety, and grand mal seizures to life-threatening delirium tremens. In one study, 20% of the alcohol-dependent patients admitted to a surgical service developed delirium tremens after admission (27). Withdrawal symptoms may appear within hours of decreased intake; however, during the peri-operative period, the administration of anesthetics, sedatives, and analgesics may delay the onset of withdrawal for up to 14 days (28). Recognizing withdrawal risk and treating early withdrawal can often prevent the complications of severe withdrawal. Because alcohol withdrawal is especially dangerous during the postoperative period, asymptomatic but at-risk patients should receive prophylactic treatment to prevent withdrawal. Although many medications have been used to treat alcohol withdrawal, benzodiazepines are the drugs of choice for both the prevention and management of alcohol withdrawal (29,30). Preferably, benzodiazepines with a long half-life such as diazepam or chlordiazepoxide should be chosen. However, patients with severe liver disease should receive a short-acting agent such as lorazepam to avoid excessive and prolonged sedation. Treatment of withdrawal should be based on the severity of symptoms and signs. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Scale for Alcohol, revised, is a validated tool that can be used to rate the severity for alcohol withdrawal (31). This 10-item scale can be completed rapidly and easily at the bedside. Use of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Scale for Alcohol, revised, may be difficult to use in the postoperative period in patients unable to verbally communicate and may be less reliable in patients with acute medical or surgical illnesses. Goals for management of alcohol withdrawal include treatment of withdrawal symptoms, prevention of initial and recurrent seizures, and prevention and treatment of delirium tremens (26).

Alcohol Use and Surgical Risk

In addition to alcohol withdrawal, numerous observational studies have demonstrated that heavy alcohol use even in the absence of clinical liver disease and even in the absence of alcohol use disorder per se is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications. Higher rates of postoperative complications were seen after transurethral prostatectomy, colonic surgery, and hysterectomy (32–34). There is a dose–response effect, with increased alcohol consumption in grams being associated with both increased postoperative complications and prolonged hospital stay. The most dramatic differences were in groups who drank greater than 60 g of alcohol (>4 drinks) per day (35). The postoperative complications reported were an increased rate of infection, bleeding, and delayed wound healing. In a prospective study of patients having colorectal surgery, Tonnesen et al. (14) found an increase in postoperative arrhythmias. Patients with alcohol dependence also have longer intensive care unit stays, more postoperative septicemia, and pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation as well as increased overall mortality (36). Five possible pathologic mechanisms have been identified to account for the increased rate of postoperative complications including immune incompetence, subclinical cardiac insufficiency, hemostatic imbalances, abnormal stress response, and wound healing dysfunction (5,8). Heavy alcohol use suppresses T-cell–dependent activity and decreases macrophage, monocyte, and neutrophil mobilization, and phagocytosis. This immune dysfunction is reversible after abstinence (35). The decrease cardiac function associated with heavy alcohol use is thought to be secondary to direct alteration in the electromechanical coupling and contractility of cardiac myocytes. This alcohol-associated cardiac dysfunction may be reversible, with 50% of patients showing improvement after 6 months of abstinence (37). The hemostatic dysfunction in people with an alcohol use disorder is due to a modification in coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways as well as a decrease in the number and function of platelets (35). Wound healing problems seems related to poor accumulation of collagen (35). Abstinence before surgery decreases postoperative morbidity. Tonnesen et al. pre-operatively randomized adults who drank at least 5 drinks per day who were scheduled for elective colorectal surgery to abstinence for 1 month before surgery versus a usual-care group (38). They observed fewer complications in the abstinent group compared with the usual-care group; however, there was no difference in length of stay or mortality. This is the first study to demonstrate that preoperative abstinence can lead to improved postoperative outcomes. It suggests that when possible, treatment of alcohol use disorder should occur preoperatively, with treatments proven to decrease alcohol use or achieve abstinence (e.g., pharmacotherapies like disulfiram and proven psychosocial approaches).

Alcoholic Liver Disease

The spectrum of liver disease associated with the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use (i.e., risky use to alcohol use disorder) includes asymptomatic fatty liver, to acute hepatitis, and finally chronic cirrhosis. Each form of liver disease carries some degree of surgical risk and requires special preoperative considerations.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver

Alcoholic fatty liver (hepatic steatosis) occurs in 90% of heavy drinkers and is often asymptomatic and reversible. It can occur after “binge” (heavy-drinking episode) or “social” drinking (excessive but without other recognized consequences). Signs and symptoms when present include nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness. Laboratory tests often demonstrate a mild elevation in liver transaminases but with preserved liver synthetic function with normal bilirubin, albumin, and coagulation studies. These signs and symptoms usually resolve within 2 weeks of abstinence (39). Patients with fatty liver seem to tolerate surgery well (40); however, there are no known studies evaluating perioperative risk in these patients. It is prudent to delay elective surgery until resolution of clinical signs and symptoms, and if possible, abstinence is achieved.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious inflammatory disease of the liver, which occurs in up to 40% of heavy drinkers. The pathologic mechanisms include hepatocyte swelling, liver infiltration with polymorphonuclear cells, and hepatocyte necrosis. These patients often present extremely ill with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, fever, and jaundice. Elevated transaminases and prolonged coagulation studies are common. Surgical risk is very high in this group, with 100% mortality rates reported in older series (41). Therefore, alcoholic hepatitis should be considered a contraindication to elective surgery. It is recommended that elective surgery be delayed until clinical and laboratory parameters normalize, sometimes taking up to 12 weeks.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis occurs in 15% to 20% of heavy drinkers and refers to the irreversible necrosis, nodular regeneration, and fibrosis of the liver. Cirrhosis is associated with abnormal hepatic circulation, resulting in portal vein hypertension. Clinically, patients may present with ascites, peripheral edema, poor nutritional status, muscle wasting, coagulopathies, gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices, encephalopathy, and renal insufficiency as well as hypoxia secondary to hepatopulmonary syndrome and pulmonary hypertension. The need for surgery is common in patients with cirrhosis, with up to 10% requiring a surgical procedure during the last 2 years of life (42). Depending on the stage of cirrhotic disease, surgery can be extremely risky. The most common causes of perioperative mortality in cirrhotic patients are sepsis, hemorrhage, and hepatorenal syndrome (43). Although currently used anesthetic agents are not hepatotoxic, surgical stress in itself causes hemodynamic changes in the liver resulting in postoperative elevations in liver function tests in patients with no underlying liver disease (44). Patients with underlying liver dysfunction are at increased risk for hepatic decompensation during surgical stress because anesthetic agents decrease hepatic blood flow by as much as 50% and therefore decrease hepatic oxygen uptake (45). Intraoperative traction on abdominal viscera may also decrease hepatic blood flow.

Effect of Cirrhosis on Surgical Risk

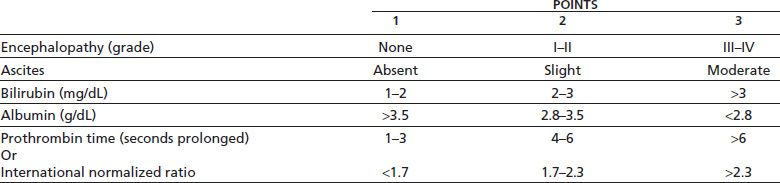

Surgery in patients with cirrhosis is high risk. A study of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty found that both local and systemic complications were as high as 44% in patients with cirrhosis versus 6% in a control group (46). The preoperative factors associated with increased surgical morbidity and mortality include emergent surgery, upper abdominal surgery, poor hepatic synthetic function, anemia, ascites, malnutrition, and encephalopathy (47). These patients are at increased risk for uncontrolled bleeding, infections, and delirium. Coagulopathies and thrombocytopenia result in difficult perioperative hemostasis. Ascites increases the risk of intra-abdominal infections, abdominal wound dehiscence, and abdominal wall herniation. Nutritional deficiencies result in poor wound healing and an increased risk of skin breakdown, and encephalopathy decreases the patient’s ability to effectively participate in postoperative rehabilitation. The action of anesthetic agents may be prolonged and increases the risk of delirium. Cholecystectomy is a particularly risky surgery in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension because of intra-abdominal collateral circulation. This collateral circulation increases the vascularity of the gallbladder bed and places the patient at greater risk for severe perioperative hemorrhage. In a group of patients with cirrhosis undergoing cholecystectomy, those considered decompensated preoperatively by presence of ascites and prolonged coagulation studies had an 83% morality rate compared with 10% in compensated patients (48). In trying to risk stratify patient preoperatively, it is important to look for clinical signs of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. There are two scoring systems in use to predict whether patients with advance liver disease will survive surgery (49). Using a multivariable clinical assessment, the Child and Turcotte Classification made it possible to risk stratify patients with cirrhosis preoperatively. In 1964, the Child and Turcotte Classification stratified cirrhotic patients into three classes based on “hepatic reserve” and therefore surgical risk before portocaval shunt surgery (50). Class A was the most compensated, whereas class C was the most decompensated group. Variables included laboratory values of bilirubin and albumin as well as clinical ascites, encephalopathy, and nutritional status. Garrison found good correlation between Child and Turcotte Classification and abdominal surgical mortality with class A, B, and C mortality rates of 10%, 31%, and 76%, respectively (51). Some of the limitations of the Child and Turcotte Classification scheme included the subjective nature and interobserver variation in the assessment of nutritional status, encephalopathy, and ascites. In addition, there was variability in the assigning of patients to classes A, B, and C and no accounting for the nature and urgency of the surgical procedure. In an attempt to decrease the subjective nature of the classification scheme, Pugh et al. modified the Child and Turcotte Classification (Table 84-1) (52). The Pugh modification separates hepatic encephalopathy into five grades depending on various signs and symptoms (Table 84-2).

TABLE 84-1 PUGH CLASSIFICATION (MODIFIED CHILD AND TURCOTTE CLASSIFICATION)

Class A 5–6 points

Class B 7–9 points

Class C 10–15 points

Adapted from Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646–649.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree