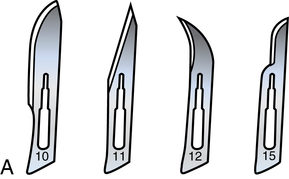

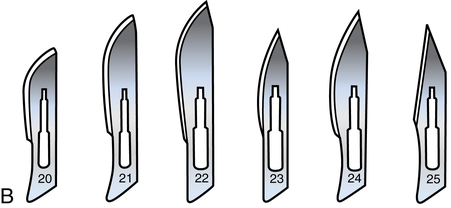

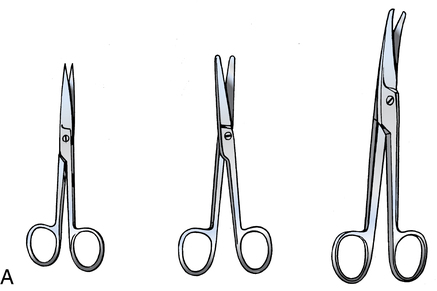

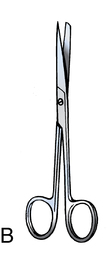

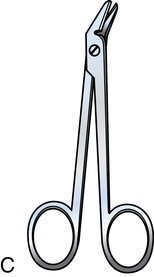

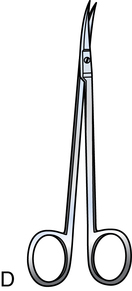

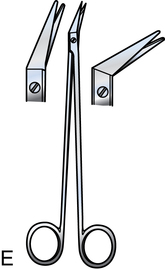

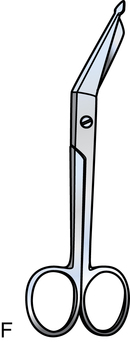

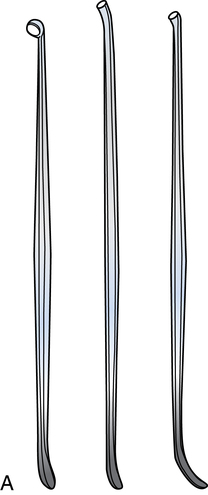

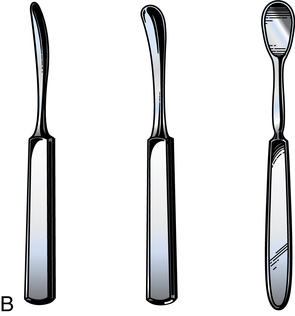

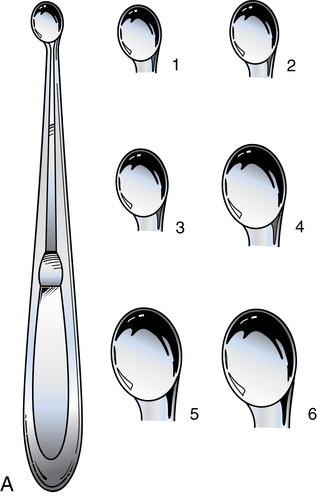

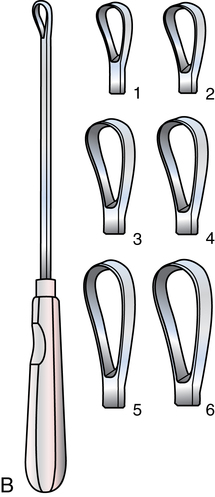

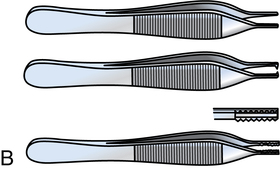

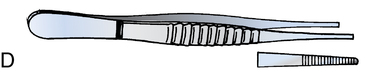

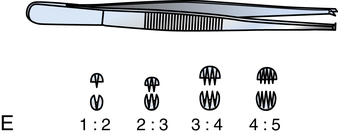

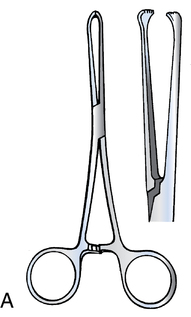

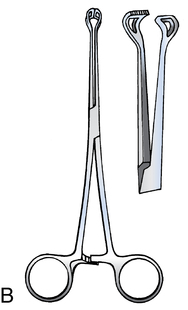

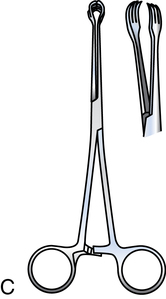

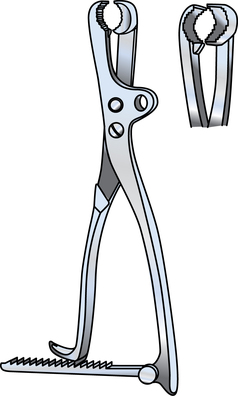

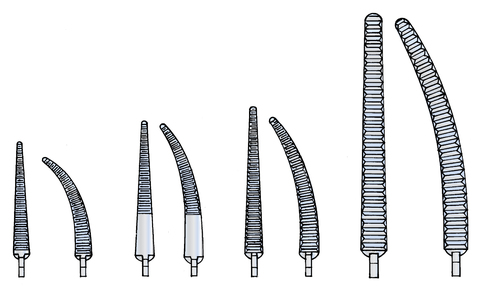

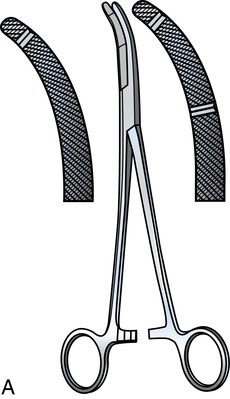

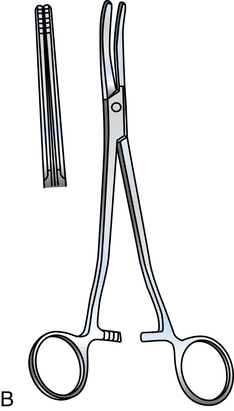

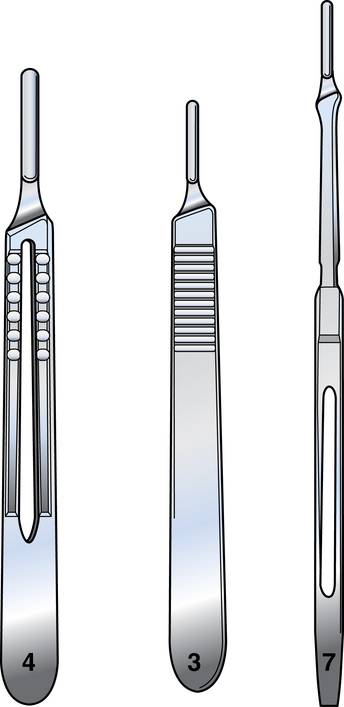

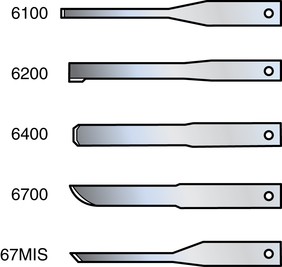

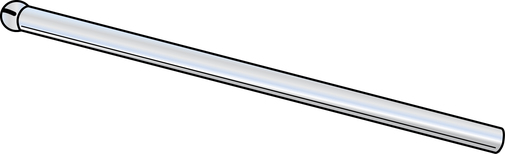

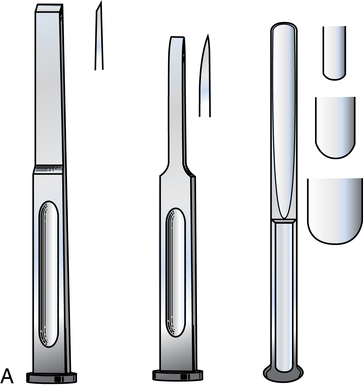

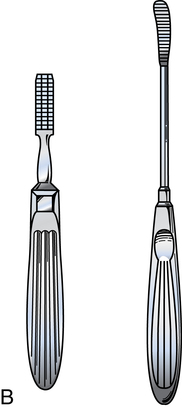

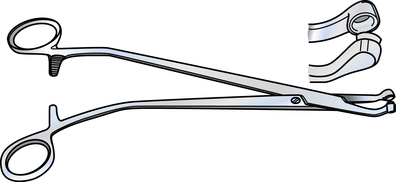

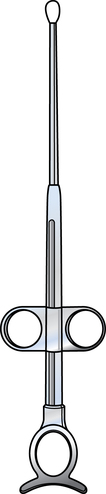

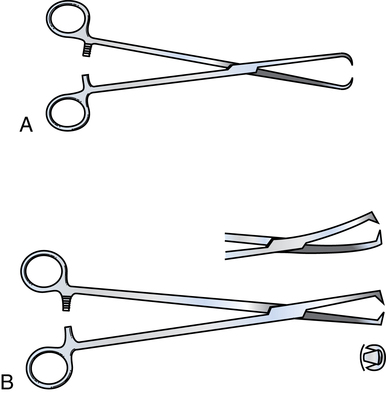

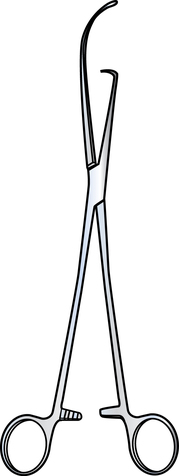

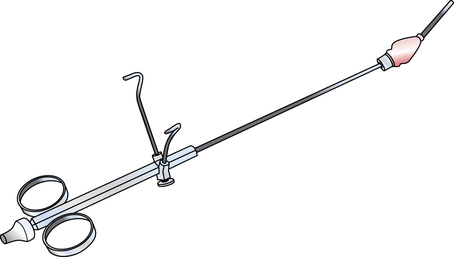

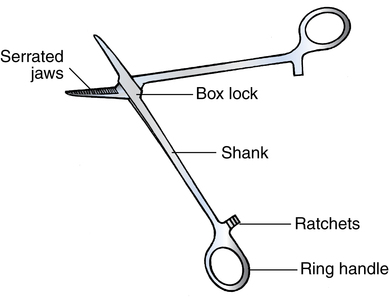

Chapter 19 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Identify the use and function of each type of surgical instrument. • Demonstrate the appropriate methods for passing each type of instrument. • Understand the rationale and methods of decontamination of instrumentation. Metallurgy is the study of metals and their properties. This science enhanced the development of surgical instruments over the centuries. Although some surgical instruments are made of titanium, cobalt-based alloy (Vitallium), or other metals, the vast majority are made of stainless steel. The alloys used must have specific properties to make them resistant to corrosion when exposed to blood and body fluids, cleaning solutions, sterilization, and the atmosphere. The manufacturer chooses the alloy for its durability, functional capacity, and ease of fabrication for the intended purpose. Stainless steel instruments are fabricated with one of three types of finishes before passivation: 1. A mirror finish is shiny and reflects light. This highly polished finish tends to resist surface corrosion, but the glare can be a distraction for the surgeon or an obstruction to visibility. 2. An anodized finish, sometimes referred to as a satin finish, is dull and nonreflective. Protective coatings of chromium and nickel are deposited electrolytically and reduce glare. This type of finish is somewhat more susceptible to surface corrosion than is a highly polished surface, but the corrosion is usually easily removed. 3. An ebonized finish is black, which eliminates glare. The surface is darkened by a process of chemical oxidation. Instruments with an ebony finish are used in laser surgery to prevent beam reflection. In other surgical procedures, instruments with an ebony finish may offer the surgeon better color contrast because they do not reflect the color of tissues. In comparison to stainless steel, the metallurgic properties of titanium are excellent for the manufacture of microsurgical instruments. Titanium is nonmagnetic and inert. Titanium alloy is harder, stronger, lighter in weight, and more resistant to corrosion than is stainless steel. A blue anodized finish of titanium oxide reduces glare. Titanium can be used in MRI procedures.2 The type of scalpel most commonly used has a reusable handle with a disposable blade. Most handles are made of brass; the blades may be made of carbon steel. Blades vary by size and shape (Fig. 19-1); handles vary by width and length (Fig. 19-2). Blades with a numeric prefix of “1” as in a “10” series (e.g., 10, 11, 12, and 15) fit handle size number 3 or 7. Blades with a numeric prefix of “2” as in “20” series (e.g., 20, 22, or 25) fit handle size number 4. Disposable scalpels also are available. • Number 10 blades are rounded toward the tip and are often used to open the skin. • Number 11 blades have a linear edge with a sharp tip. Can be used to make the initial skin puncture for tiny deep incisions. • Number 12 blades have a curved cutting surface like a hook. Commonly used for tonsillectomy. • Number 15 blades have a short rounded edge for shallow short controlled incisions. • Number 20 blades are shaped similar to number 10 blades but larger. • An assortment of blades with angulations and configurations for specific uses, such as a Beaver blade, also are used (Fig. 19-3). These blades insert into a special universal handle that secures by turning a screw-in collar (Fig. 19-4). The blades of scissors may be straight, angled, or curved, as well as either wedge-shaped, sharp, blunt, or combined sharp-blunt tips (Fig. 19-5). The handles may be long or short. Some scissors are used only to cut or dissect tissues; others are used to cut other materials. To maintain sharpness of the cutting edges and proper alignment of the blades, scissors should be used only for their intended purpose: • Tissue/dissecting scissors have sharp or blunt tips. The type and location of tissue to be cut determine which scissors the surgeon will use. Blades needed to cut tough tissues are heavier than those needed to cut fine, delicate structures. Curved or angled blades are needed to reach under or around structures. Tissue scissors with blunt tips can be used to bluntly dissect between individual planes before sharply dissecting. Handles to reach deep into body cavities are longer than those needed for superficial tissues (Fig. 19-5, A). • Suture scissors have sharp-blunt points to prevent structures close to the suture from being cut. The scrub person may use scissors to cut sutures during preparation if needed (Fig. 19-5, B). • Wire scissors have short, heavy serrated blades. Wire scissors are used instead of suture scissors to cut stainless steel sutures. (Fig. 19-5, C). Heavy wire cutters are used to cut bone fixation wires. • Short jaw sharp-tipped scissors are used for deep, confined areas such as the nasal cavity (Fig. 19-5, D). • Sharp-tipped angled scissors with short jaws are used for vascular surgery (Fig. 19-5, E). • Dressing/bandage scissors are used to cut drains and dressings and to open items such as plastic packets (Fig. 19-5, F). The protective tip prevents cutting into concealed structures. • Small scissors with specially wedge-shaped tips such as tenotomy scissors (Fig. 19-5, G) Friable tissues or tissue planes can be separated by blunt dissection. The scalpel handle, the blunt sides of tissue scissors blades, and dissecting sponges may be used for this purpose (Fig 19-6). Elevators, strippers, and dissectors can be used to remove adherent tissue such as periosteum from bone or dura from the inner aspect of the skull. Debulking instruments include chisels, osteotomes, gouges, rasps, and files (Fig. 19-7). The purpose of these instruments is to decrease the bulk of firm tissue and not necessarily cut along defined tissue planes. • Biopsy forceps and punches. A small piece of tissue for pathologic examination may be removed with a biopsy forceps or punch. These instruments may be used through an endoscope (Fig. 19-8). • Curettes. Soft tissue or bone is removed by scraping with the sharp edge of the loop, ring, or scoop on the end of a curette (Fig. 19-9). • Snares. A loop of wire may be put around a pedicle to dissect tissue such as a tonsil or a polyp. The wire cuts the pedicle as it retracts into the instrument. The wire is discarded and replaced with a new one after use (Fig. 19-10). Tissues should be grasped atraumatically and held in position so the surgeon can perform the desired maneuver, such as dissecting or suturing (approximating), without injuring the surrounding subcutaneous tissues or perforating the skin (Fig. 19-11). Forceps without ring handles are commonly referred to as pick-ups. Also referred to as thumb forceps or pick-ups, smooth forceps resemble tweezers. They are tapered and have serrations (grooves) at the tip. They may be straight or bayonet (angled), short or long, and delicate or heavy. Smooth forceps are atraumatic and will not injure delicate structures (Fig. 19-11, D). Toothed forceps differ from smooth forceps at the tip. Rather than being serrated, they have a single tooth on one side that fits between two teeth on the opposing side or they have a row of multiple teeth at the tip. Heavy types are sometimes referred to as rat-toothed forceps. Toothed forceps provide a firm hold on tough tissues, including skin. Finer versions have delicate teeth for holding more delicate tissue (Fig. 19-11, E). Allis forceps have ringed handles and lock with ratchets. Each jaw curves slightly inward, and there is a row of teeth at the end. The teeth grasp tissue edges securely (Fig. 19-12, A). Allis forceps can be short or long. Some of the long forceps have a slight curve, such as those used with a hemorrhoid band ligator. Babcock forceps have ringed handles and lock with ratchets. The end of each jaw of a Babcock forceps is rounded to fit around a tubular structure (i.e., fallopian tube) or to grasp tissue without injury. This rounded section is circumferentially fenestrated (Fig. 19-12, B). Babcock forceps are straight and can be short or long; they are not occlusive or crushing. Tenaculums have ringed handles and lock with ratchets and may have a single tooth or multiple teeth, such as a Jacob tenaculum (Fig. 19-13). The curved or angled points on the ends of the jaws of tenaculums penetrate tissue to grasp firmly, such as when a uterine tenaculum is attached to the cervix and used to manipulate the uterus during laparoscopy. Some uterine tenaculums have a built-in uterine cannula or probe elevator tip, such as a Hulka tenaculum (Fig. 19-14). A uterine cannula, or probe, can be used during laparoscopy to raise the uterus into the visual field (Fig. 19-15). The cannula tip is inserted into the cervical os as the tenaculum is clamped on the anterior aspect of the cervix. Dye or contrast media can be instilled through the cannula into the uterine cavity to visualize tubal patency or the inner configuration of the uterine cavity. Some styles have a tenaculum stabilizer attached. Most clamps used for occluding blood vessels have two opposing jaws (with or without serrations or teeth), ringed handles, and lock with ratchets. Most ring-handled clamps have a common design (Fig. 19-17). The length and shape of the shanks or jaws may vary according to the intended function of the instrument. Hemostats are the most commonly used surgical instruments and are used primarily to clamp blood vessels. They have a crushing action. Hemostats have either straight or curved slender jaws that taper to a fine point. The serrations are longitudinal or horizontal inside the jaws (Fig. 19-18). Many variations of hemostatic forceps are used to crush tissues or clamp blood vessels. The jaws may be straight, curved, or angled, and the serrations may be horizontal, diagonal, or longitudinal. The tip may be pointed or rounded or have a tooth along the jaw such as on a Heaney or hysterectomy clamps (Fig. 19-19). The length of the jaws and handles varies. Many forceps are named for the surgeon who designed the style, such as the Kocher and the Ochsner clamps (Fig. 19-20).

Surgical instrumentation

Fabrication of metal instruments

Stainless steel

Titanium

Classification of instruments

Dissecting and cutting instruments

Scalpels

Scissors

Blunt dissectors

Debulking instruments

Grasping and holding instruments

Smooth tissue forceps

Toothed tissue forceps

Allis forceps

Babcock forceps

Tenaculums

Clamping and occluding instruments

Hemostatic clamps

Hemostats

Crushing clamps

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgical instrumentation

Website

Website