51

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Current interest in office-based approaches to the treatment of opioid addiction springs from a recognition that the numbers and needs of opioid-dependent individuals continue to overwhelm the capacity of the traditional, program-based treatment system. Many such individuals cannot gain access to opioid agonist therapy, which is the most effective intervention yet devised for this disorder (1). Meanwhile, indicators of opioid-related health care costs and criminal justice contacts continue to surge (2,3), as do the number of opioid-related deaths (4). Many opioid-dependent individuals also have unique and serious medical and psychiatric problems that the program-based treatment system cannot always address and that contribute to morbidity and mortality (1). Office-based opioid therapy (OBOT) offers one potential avenue and has made substantial inroads in the drive to ameliorate this unsatisfactory situation.

This chapter reviews some of the historic and regulatory events that shaped the current treatment system in the United States and account for some of the ongoing gaps in services for opioid-dependent individuals. Office-based treatment effectively fills some of these gaps, in part because office-based treatment encompasses two distinct treatment paradigms. First, OBOT offers a less structured, more flexible, and more personalized form of intervention for opioid-dependent patients who have succeeded in the traditional treatment system of opioid agonist clinics licensed by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration but who need to continue in pharmacotherapy. Second, OBOT provides an alternative route of entry into treatment for opioid-dependent individuals who, for a variety of reasons, have not had access to adequate treatment or to reengagement in treatment for individuals who have not achieved their goals in the traditional treatment system.

A summary of the evidence for the benefits of transferring selected, stable methadone-treated patients into office-based settings precedes a synopsis of efforts to apply and evaluate the office-based approach for less stable patients newly entering treatment. Results of these investigations of office-based treatment then guide a discussion of clinical issues pertinent to conducting office-based treatment with opioid-dependent patients.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC AND REGULATORY ISSUES

During the first few years of the 21st century, the purity of heroin sold in the United States continued to increase, while the price decreased (5). Heroin-related emergency department visits have increased from 33,900 in 1990 to 213,118 in 2009 (6). Heroin-related overdose deaths reported to the Drug Abuse Warning Network increased from 2,300 in 1991 to 4,330 in 1998 (7,8). Heroin overdose deaths are no longer reported on a nationwide basis but rather by metropolitan and state areas. As of 2009, these deaths were still occurring in large numbers (9). Overdose accounts for only half the overall observed mortality in heroin users, who exhibit mortality rates 6 to 20 times those of age-matched populations (9,10).

A subset of the heroin-using population engages in repeated criminal activity (11). The Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program (12) provides urine toxicology results of 4,182 male arrestees in 10 counties around the country. These data show that, in 2010, rates of adult male arrestees testing positive for recent opiate use varied around the country from a low of 3% in Charlotte, North Carolina, to a high of 22% in Portland, Oregon, and that rates of testing positive increased at most sites from 2007 to 2010.

The past decade has also seen a surge in the illicit use of and problems with prescription opioid medications. In 2009, the number [416,458] of emergency room visits related to nonmedical use of prescription opioids more than doubled from 2005 and exceeded the number for heroin [213,118] (6). Large numbers of overdoses on prescription opioids have also been noted (4). In 2010, as many people abused OxyContin in the past month (0.2 million) as used heroin, and 5.1 million abused some type of pain reliever (primarily hydrocodone and oxycodone) in the past month (13).

Despite these trends, most opioid-dependent individuals cannot access adequate treatment services. In 2010, approximately 256,000 individuals entered treatment for heroin dependence, but only 27.9% received medication-assisted treatment. Similarly, 157,000 entered treatment for dependence on other opioids, but only 20% received medication-assisted treatment (14). These data reflect a circumstance that has been prevalent throughout the past 100 years. However, these data do not reflect individuals receiving office-based opioid treatment, which is making medication-assisted treatment more widely available.

The mobilization of office-based treatment as a response to this problem does not represent a true innovation but rather a return to a once commonly used strategy. Thousands of untreated opioid-dependent individuals also worried society in the early part of the 20th century. Before the Harrison Narcotic Act was enacted in 1914 (see Chapter 22, “Addiction Medicine in America: Its Birth and Early History (1750–1935) with a Modern Postscript”), no legal restrictions limited the right of physicians to prescribe opioid medications for the care of patients considered addicted. Although controversy raged then, as it does now, about how best to handle opioid-dependent individuals, many experts of that generation already had recognized the high likelihood that opioid-dependent patients would resume opioid use after enforced withdrawal. Physicians in many areas of the country thus viewed opioid addiction as a medical disorder; they advocated and practiced the ongoing prescribing of opioids from their offices as a reasonable and apparently useful way to manage the problem.

Most of these physicians conducted this part of their work in a responsible way. A minority may have allowed their practices to become conduits for controlled substances out of a profit motive without always providing adequate medical care. On the basis of a small number of reports of this type of inappropriate prescribing, concern about the safety and wisdom of prescribing opioids to opioid-dependent individuals increased in the medical profession itself as well as among regulators and the general public. In 1919, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Harrison Act disallowed such physician prescribing to opioid-dependent individuals for “maintenance” purposes (14). This decision effectively ended the first era of office-based treatment for opioid addiction.

Such a wholesale shift in policy left patients without access to the opioids on which they depended. Many municipalities responded by creating publicly funded and administered opioid maintenance clinics (15). For example, when New York City experienced one of its waves of heroin addiction after World War I, a clinic under the auspices of the city health department treated 8,000 heroin-dependent patients with prescribed heroin (16). These pioneer efforts at agonist pharmacotherapy ended within a few years when the Narcotic Division of the Federal Prohibition Unit shut down these maintenance clinics as violators of the Harrison Act (15). Thus, from the 1920s onward, physicians were actively discouraged from treating heroin-dependent individuals, and indeed, medical school curricula provided no training to physicians in this regard. In essence, opioid addiction was reconceptualized as a criminal justice rather than a medical problem. Convicted violators of federal narcotics laws caused an overload in the federal penal system, so the Congress established federal narcotics hospitals at Lexington, KY, and Forth Worth, TX, in the 1930s. Despite high recidivism rates, these isolated facilities remained the only treatment option for opioid-dependent individuals until the advent of methadone maintenance 30 years later (15).

In some respects, the severance of opioid addiction treatment from the general practice of medicine actually was exaggerated in the 1970s when opioid agonist therapy, in the form of methadone maintenance, once again was permitted and, to some extent, promulgated. Federal methadone regulations (21 CFR Part 291) promulgated in 1972 and the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 1974 mandated a closed distribution system for methadone, with special licensing by both federal and state authorities. These regulations effectively made it illegal for physicians not associated with a licensed program to treat opioid-dependent patients with agonist pharmacotherapy in an office setting. Until 2003, a private physician would have to obtain an additional registration from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, annual certification by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and approval by state drug authorities to provide opioid agonist therapy (17). Only a small number of physicians around the country have been willing to negotiate this bureaucratic maze. As a result, the only option for patients who desired opioid agonist pharmacotherapy was to enroll in a specialized, licensed methadone treatment program. Once again, most practicing physicians were deprived of exposure to and experience in treating opioid-dependent patients.

The divergence between mainstream medicine and opioid addiction treatment has had some unfortunate consequences. Opioid addiction causes considerable medical morbidity as a consequence of drug effects and intravenous route of administration (18). Medical problems common in users of illicit opiates include infectious diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, endocarditis, as well as sexually transmitted diseases (19); soft tissue infections (20); bone and joint infections (21); central nervous system infections (22); and viral hepatitis (23), particularly hepatitis C (24). In addition, HIV infection and AIDS pose a massive problem among intravenous drug users (23,25). Noninfectious problems also typically occur in the lungs (26), the central and peripheral nervous systems (22), the vascular system (20), and the musculoskeletal system (20). Licensed opioid agonist treatment programs often lack the resources to provide comprehensive medical care (17), with the result that comorbid medical disorders may be unattended, delaying care and driving up its ultimate cost. Total health care costs related to heroin addiction were $5 billion annually in the United States in 1996 (27).

Similarly, a high prevalence of Axis I psychiatric comorbidity, particularly mood and anxiety disorders, is seen among patients who are addicted to opioids (28,29), and licensed programs typically cannot provide the treatment these conditions require (17).

As the divide between general medical practice and opioid agonist treatment is bridged, patients have improved access to simultaneous care for these serious comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.

Many potential patients who need and desire opioid agonist treatment and are willing to enroll in licensed programs cannot overcome the barriers to entry. Geography creates an impossible hurdle for some. Two states (North Dakota and Wyoming) do not offer licensed opioid agonist treatment programs. Idaho, Mississippi, Montana, and South Dakota just added programs within the last decade. In states that do offer such programs, the licensed clinics, by virtue of economic necessity and neighborhood acceptance, tend to be sited primarily in urban locations (17,30). Even within larger metropolitan areas, specific neighborhoods or communities can bar licensed clinics (17,31). A few patients who reside in states or communities without opioid agonist clinics or in rural areas invest considerable effort in traveling to other states or cities to obtain treatment; most who cannot afford the time or cost simply must forgo it (30).

Inadequate treatment capacity creates another barrier for potential patients who do live in reasonable proximity to a licensed clinic (32). Many clinics have waiting lists that discourage potential patients from even attempting entry (33). Many more potential patients lack the financial resources to pay for their treatment (33). Although OBOT does not necessarily cost less than treatment in a licensed clinic, insurance companies and managed care organizations frequently reimburse at least some of the expense of physician office visits, particularly if comorbid conditions are addressed (32).

Finally, the very nature of licensed opioid agonist treatment clinics, with the potential to be recognized and stigmatized by passersby, waiting lines for medication administration, rigid attendance policies, and lack of privacy, deters some potential patients (34).

Many of the latter concerns pertain most directly to long-term, stable patients who have achieved a measure of rehabilitation in opioid agonist treatment. Such patients have ceased illicit drug use and, in most cases, have employment and family responsibilities (32,35). To make their schedules accommodate frequent clinic visits with waits for medication, to hold up their travel plans to obtain regulatory approval, and to bring them to a locale where unstable patients with residual drug use congregate may undermine rather than support their rehabilitation (32,35). In addition, many of these rehabilitated patients already have derived maximum benefit from counseling and other services available at licensed clinics. Moving stable patients out of the restrictive clinic setting while continuing their agonist pharmacotherapy would permit reallocation of clinic resources to patients who most need them.

Three important developments altered the landscape. Since March 2000, the licensed opioid agonist treatment programs can apply for exceptions so that stable, long-term patients can enter methadone medical maintenance and have visits to obtain medication less frequently than once per week. The Children’s Health Act of 2000, signed into law in October 2000, included a provision waiving the requirements of the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act to permit qualified physicians to dispense or prescribe Schedule III, IV, or V narcotic drugs or combinations of such drugs that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of opioid addiction. This change, termed the Drug Addiction Treatment Act, allows qualified physicians to prescribe certain opioid agonist medications in an office-based setting. In October 2002, the FDA approved buprenorphine and buprenorphine + naloxone for the treatment of opioid dependence. These medications were placed in Schedule III and so are available for use in OBOT.

Clearly, the current US treatment system cannot accommodate all the opioid-dependent individuals who want or need treatment. A century ago, office-based treatment met with some success in the United States. The current resurrection of office-based treatment has helped to remove geographic, social, and regulatory barriers for both new and rehabilitated patients and thus make opioid agonist treatment more widely available. Because of the divide between opioid agonist treatment and general medical practice, some physician education and training in management of opioid-dependent patients with pharmacotherapy have been necessary, have been delivered, and will continue to occur. Considerable data, described in detail in the subsequent text, offer instruction to physicians.

RESEARCH ISSUES

Research Related to Stable, Long-Term Patients in Office-Based Practice

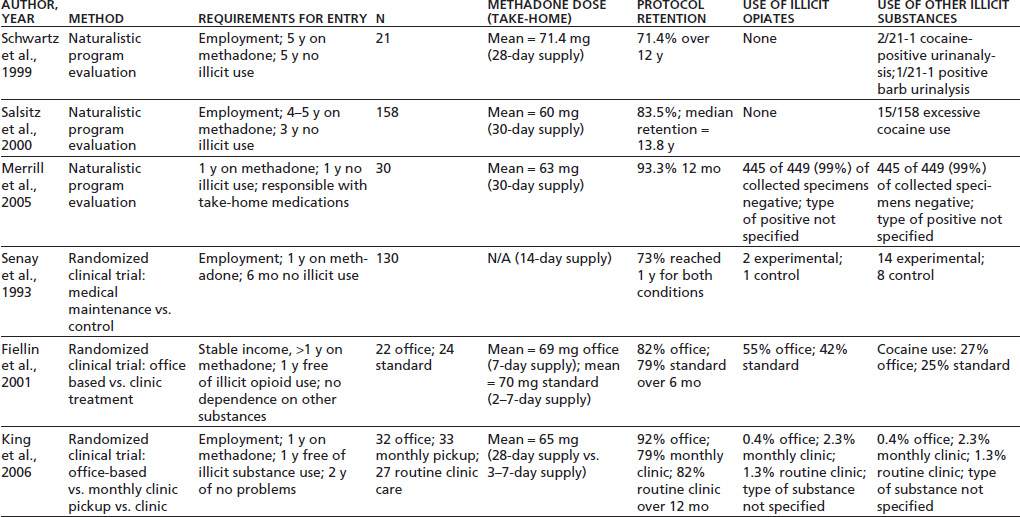

Several investigations have demonstrated the general safety and utility of transferring patients who have achieved specified degrees of stability through initial treatment in a licensed methadone clinic into an office-based setting (Table 51-1). The concept of transferring stable methadone patients to office-based practice originated with Novick et al. (36–38) of New York City, who have used this procedure since 1983 and have documented their findings in several reports over the years.

TABLE 51-1 STUDIES OF STABLE METHADONE-TREATED PATIENTS TRANSFERRED TO OBOT

A summary of their work describes outcomes for 158 total patients (35). Stringent standards were set for patients to participate in the program. Until 1996, patients were required to have completed 5 years of methadone treatment; this requirement subsequently was reduced to 4 years, though all patients actually accepted had at least 6 years of methadone treatment. At the time of entry, all participants had to have at least 3 years without illicit drug use, excessive alcohol use, or criminal activity. All had to verify employment or other productive activity. Additional criteria addressed the need for financial, emotional, and social stability. Patients who met the criteria were transferred from their methadone programs to the care of internists or family physicians in a hospital-based practice. The physicians, most of whom had little familiarity with treating opioid addiction, received specific training from physicians with experience in methadone agonist treatment. The average methadone dose at entry was 60 mg/d. Patients attended two office visits in the first month and then advanced to a monthly reporting and dosing schedule. At each office visit, they provided a specimen for urine toxicology screening and took a dose of methadone under observation to confirm tolerance. They received annual physical examinations from their office-based provider along with routine medical care as needed.

To remain in compliance with the office-based program, patients had to avoid methadone misuse or loss, avoid illicit drug use, attend all appointments, pay fees, and maintain acceptable office comportment. Only 26 patients (16.5%) ever failed to meet these standards, 15 for uncontrollable use of cocaine, and 11 for other violations. Eighteen of the “failed patients” returned to their clinics of origin. Patients had a projected median retention time of 13.8 years in office-based treatment. During the years of this investigation, 12 subjects voluntarily and successfully tapered off methadone. Of 99 active patients, 27 required dose increases, while 10 achieved dose reductions.

A retrospective analysis detected several differences between successful and unsuccessful office-based patients. Successful patients were more likely to be married or in stable relationships, were more likely to have had multiple prior treatment episodes in traditional methadone programs, and had more total years of treatment in traditional methadone programs before entering office-based treatment.

A similar, though smaller, uncontrolled trial was conducted in Baltimore by Schwartz et al. (32). The sample consisted of 21 patients enrolled during a 4-month period in 1985 and 1986. This program required that patients have at least 5 years’ documented abstinence from illicit drug use in a traditional methadone program and a record of no alcohol misuse. Patients also were required to have self-supporting employment and emotional and social stability. Those who used psychotropic medications for psychiatric disorders were excluded. All patients transferred to the private office practice were under the care of a single physician. For the first 6 months, patients visited the office every 2 weeks, at which time they gave a urine specimen, had a brief interview with the physician, and received a 14-day supply of methadone. They subsequently advanced to visits every 28 days and a 28-day supply of medication. Only minor medical problems were addressed by the primary practitioner, with most health care services delivered by outside referral. Average methadone dose over the course of the project was 71.4 mg/d. To remain in compliance with the office-based program, patients had to avoid methadone misuse or loss, have accurate return of outstanding medication doses during a “callback” procedure, avoid illicit drug or alcohol use, attend all appointments, and avoid legal problems leading to arrest.

During 12 years of follow-up, six patients (28.6%) failed to comply and were transferred back to their original methadone program: two for legal problems, three for positive urine tests, and one for a combination of problems. Of all urine specimens collected, only 0.5% showed any positive results. Not a single patient failed any of the 65 random medication callbacks conducted.

A third uncontrolled trial of the transfer of stable clinic-treated patients to an office-based setting was conducted in Seattle (39). The two programs described earlier gained permission to provide methadone treatment outside the established guidelines by obtaining an Investigational New Drug approval by the FDA to conduct research. The Seattle program was the first to obtain extensive FDA waivers to establish a clinical program allowing stabilized patients to receive methadone in a medical setting, with extended take-home privileges. Thirty-one patients who attended the licensed methadone clinic no more often than three times a week and who had 12 months of clinical stability (demonstrating responsibility with take-home medication, no urine drug tests positive for illicit drugs, consistent clinic attendance, and psychiatric stability) were transferred to an internal medicine clinic in a public hospital for primary medical care and methadone treatment. General internal medicine specialists cared for the patients after attending several training sessions on opioid addiction and agonist therapy. Ongoing counseling beyond physician visits was not required but was available through the licensed clinic. Trained pharmacists dispensed the medication through a satellite hospital pharmacy in the medical clinic.

Patients who demonstrated stability in office-based care could be advanced to monthly medication pickups. Subjects supplied monthly urine toxicology specimens and had to comply with periodic medication callbacks. Patients who required intensive monitoring or treatment could be returned immediately to the licensed methadone clinic. Twelve-month results showed that 28 of 30 patients were still in office-based treatment, with 2 patients choosing to leave the program voluntarily. Only two patients provided any drug-containing urine toxicology specimens, and 99% of collected specimens were negative.

An additional recent retrospective study of 127 methadone patients transferred to an office-based setting had similar positive results (40).

Although the investigations described certainly suggest that most highly stable methadone patients can safely transfer to office-based care, the lack of control groups in these open trials precludes conclusions about whether fewer subjects would deteriorate if they remained in traditional methadone clinics. A few controlled investigations of stable methadone patients in office-based practice have been completed. The largest of these controlled trials, although a very worthwhile study that addressed many of the concerns pertinent to office-based practice, did not represent, in the strictest sense, a trial of office-based practice because of the methodology employed. In the study, Senay et al. (41) worked with a group of 130 patients who had received at least 1 year of methadone treatment, who had 6 months of negative urine toxicologies, steady employment or productive activity, no arrests, general program compliance, and no current legal involvement. Patients were assigned randomly to either an experimental (two of three subjects) or a control condition (one of three subjects). The experimental condition consisted of a monthly visit with a physician; observed ingestion of methadone every 14 days, with 13 take-home doses for use between visits; three random urine toxicology screens per year; and random medication callbacks. Patients were required to attend at least one counseling session and leave one nonrandom urine specimen per month in their clinic of origin. Thus, the experimental subjects did continue ongoing contact with their traditional methadone programs, a situation not typical of most office-based paradigms. The control subjects remained in their clinics of origin for 6 months and then entered the experimental program. The report of this study did not provide methadone dose levels. Subjects continued in either the experimental or control conditions if they provided negative urine specimens, paid their fees, and refrained from criminal activity or lateness. During the first 6 months, 89% of experimental and 85% of control subjects remained in the program. At 1 year, 73% of both groups remained. Of the patients removed from the program, 70% were for positive urine specimens, and 30% were for other causes. Removal rates did not differ by condition. The report of this study does not mention the results of the medication callbacks. The advantages of this study derive from its randomized, controlled methodology and from its enrollment of subjects who had far less time in traditional methadone programs and less stable time than did the subjects in the studies described earlier by Salsitz et al. (35) or Schwartz et al. (32). Obviously, subjects of the type in the Senay et al. (41) study comprise a much larger proportion of typical methadone clinic populations than do the exceedingly stable patients in the other studies. The disadvantage of the Senay study resides in the fact that all subjects continued some attendance and counseling at their clinics of origin. Hence, the study really only demonstrates that most moderately stable methadone patients can manage adequately with observed ingestion of medication only once every 14 days and monthly contact with a physician, but it conveys little about office-based practice independent of a traditional methadone program.

Two small controlled studies have, however, assessed office-based practice for stable methadone patients without confounds from ongoing clinic involvement. In one study (42), 46 patients already receiving methadone agonist therapy at a licensed treatment program were randomly assigned to be transferred to office-based treatment with an internal medicine physician (n = 22) or to remain in standard clinic treatment (n = 24). Eligibility requirements for participants included more than a year of methadone treatment; 1-year abstinence from use of illicit opiates, as reflected by negative monthly random urine specimens; no current evidence of dependence on other substances; no significant medical or psychiatric conditions that could be compromised by the transfer; a source of legal income; and stable housing. Of note is the fact that only slightly more than 10% of the clinic’s total population met these criteria, which clearly are less stringent than those employed in the studies by Salsitz et al. (35) and Schwartz et al. (32). The average methadone dose for the subjects assigned to the office-based treatment condition was 69 mg. The average dose for those assigned to remain in standard clinic treatment was 70 mg. The six physicians who provided the office-based treatment and their staff members received training in management of patients on opioid agonist therapy.

Subjects assigned to office-based treatment received a weekly supply of methadone from the physician’s office. They had an initial 1-hour office visit in which a history and physical were performed. They subsequently met with their physician monthly. Subjects assigned to remain in standard clinic treatment came to the clinic one to three times a week to pick up their methadone. All subjects provided monthly urine specimens and quarterly hair specimens for toxicologic analysis. If a patient’s urine was positive for opiates or cocaine or negative for methadone, a repeat urine specimen was obtained within 1 week. If this repeat specimen also tested positive for opiates or cocaine or negative for methadone, patients were considered out of compliance with the protocol, removed from the study, and transferred back to routine care. During a 6-month follow-up interval, 18% of the office-based subjects and 21% of the standard clinic subjects violated the study criteria and were transferred back to routine care. By urinalysis, hair toxicology, or self-report, 55% of office-based and 42% of standard clinic subjects had evidence of illicit opiate use, and 27% and 25%, respectively, had evidence of cocaine use.

Hair toxicology testing at baseline in this study allowed for some valuable observations. Though all subjects had submitted 12 consecutive negative monthly urine specimens before entering the study, hair testing found evidence of illicit drug use in the preceding 90 days by 44% of the subjects. Though the failure of monthly urine testing to detect all substance use does not come as a surprise (43), positive hair testing at baseline did act as a predictor of substance use during follow-up. Among those with positive hair toxicology at baseline, 90% had evidence of illicit use during follow-up. In contrast, only 20% of those with negative baseline hair toxicology had such evidence at follow-up.

In another controlled study (44,45), 98 subjects who were receiving methadone treatment were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (i) medication pickup every 28 days in a physician’s office away from the licensed treatment program; (ii) medication pickup every 28 days, with a monthly physician visit at the licensed treatment clinic; or (iii) continued routine clinic care, with medication pickup once or twice a week at the clinic. Of those randomly assigned, six declined further participation after receiving their treatment assignment and were terminated from the study. Eligibility requirements for participants included continuous methadone treatment and absence of any positive monthly urine specimens over the preceding 12 months, full-time employment, and no failed medication recalls or problems handling medication over the preceding 24 months. About 25% of patients from two different clinics met these criteria. The average methadone dose was 65 mg/d. The four physicians who provided the office-based treatment had previous experience treating patients with methadone agonist therapy. All subjects received a single 20-minute counseling session per month. The 28-day pickup subjects received counseling from their physicians. The routine care subjects received counseling from clinic counselors. All subjects submitted to a monthly random medication recall procedure. All subjects gave two urine specimens per month. The 28-day pickup subjects provided a routine, nonrandom specimen at the time of their scheduled physician visits and also produced a random urine specimen at the time of the medication recall. The routine care patients gave a routine random urine specimen once a month, just as did the other clinic patients, and provided a second random specimen at the time of their medication recall. An innovative stepped-care counseling intensification procedure was used so that subjects who exhibited problems such as a positive urine specimen or failed medication recall could be transferred back to the clinic for five weekly medication visits until they again attained stability. They would then resume treatment in their assigned research condition. Treatment retention at 12 months was 82% for routine clinic care, 79% for clinic-based medical maintenance, and 92% for office-based medical maintenance. Only 12 patients submitted positive urine specimens over 12 months (9 had one positive, 2 had two positives, and 1 had repeated positive specimens for cocaine and benzodiazepines), while nearly 30% of patients failed at least one medication recall. These problems resulted in 33 subjects’ (36%) entering intensified counseling. The three groups did not differ significantly in the likelihood that patients would experience any negative outcome.

Consideration of the overall data obtained from patients who have achieved some measure of stability on methadone therapy delivered in a clinic setting shows fairly convincingly that most can transfer successfully to office-based care. In addition, in virtually all cases, patients who fail in office-based treatment because of substance relapse or rule violations can be returned to routine clinic care to receive intensified counseling and monitoring without undue harm. The controlled studies also suggest that relapse or other problems in previously stable patients in office-based practice occur at rates no greater than those of similarly stable patients who remain in routine clinic care.

Research Related to Patients Entering Directly into Office-Based Practice

Although policies and attitudes in the United States had, until 2000, steered practitioners away from the idea of bringing unstable opioid-dependent individuals directly into office-based treatment, other countries have, out of necessity and an innovative spirit, embraced this concept more quickly (Table 51-2).

TABLE 51-2 STUDIES OF PATIENTS ADMITTED DIRECTLY TO OFFICE-BASED OPIOID TREATMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree