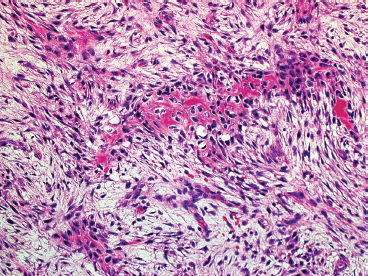

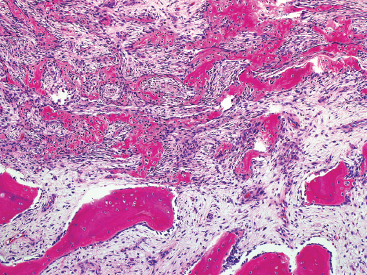

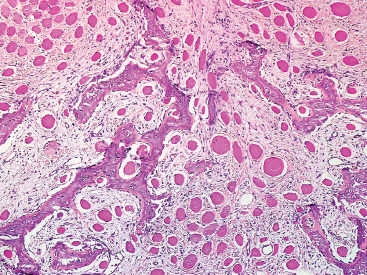

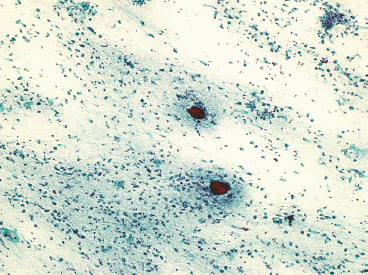

SOFT TISSUE TUMORS WITH OSSEOUS OR CARTILAGINOUS MATRIX 14.2 Phosphaturic Mesenchymal Tumor 14.5 Ossifying Fibromyxoid Tumor of Soft Parts 14.6 Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma and Chondrosarcoma Myositis ossificans (MO) represents one of the “pseudotumors” of soft tissue that was at one time thought to be reactive, but is now known to be a self-limited neoplastic process. MO has a predilection for young, active individuals and occurs in sites that are easily traumatized. One of the most common locations is in the soft tissue of the lower extremity, but MO has been reported on the trunk, chest wall, elbow, and shoulder. A histologically similar lesion, termed fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit (FOPD), occurs in the fingers and toes, most commonly in the proximal phalanx (Figure 14.1.1). In addition, there is a “periostitis ossificans” that occurs on or in the periosteum of the bone, usually one of the long bones. Patients present with a rapidly growing and painful soft tissue mass in the digits; there may be redness and swelling as well. In most instances, there is a history of traumatic injury to the affected region. In those lacking history, the mechanism of formation is thought to be some type of subclinical, repetitive pattern of soft tissue injury. On imaging, MO has a characteristic appearance if the lesion is mature enough to have begun the process of calcification. This occurs variably several weeks after the onset of symptoms, when dense calcifications begin to appear around the periphery of the injured soft tissue. Eventually the calcification coalesces to form an egg-shell type of rim around the lesion. This feature is demonstrable on many types of imaging, including CT, MRI, and plain films (Figure 14.1.2). Given time, the lesion will become completely ossified and may eventually be partially or completely resorbed. Rearrangements of USP6 have been identified in a subset of cases of MO. The histology of MO is variable, depending on the “age” of the biopsied or excised lesion. Very immature lesions may closely resemble nodular fasciitis with an edematous stroma and entrapped skeletal muscle fibers. As the lesion “matures,” fragments of immature woven bone are formed at the periphery of the lesion. The interior of the lesion remains more cellular and disorganized, resulting in the “zonation” phenomenon that is characteristic of MO (Figure 14.1.3). The bone trabeculae are composed of woven bone, often show a rim of plump osteoblasts, and often entrap fibers of skeletal muscle (Figure 14.1.4). There may also be islands of immature-appearing cartilage that undergo ossification. Centrally, the lesion is composed of plump myofibroblastic cells arranged in a haphazard pattern (Figure 14.1.5). The stroma may contain extravasated red blood cells, inflammatory cells, and osteoclast-like giant cells. Mitoses are usually numerous, but atypical mitotic figures should not be identified. Very mature MO may undergo complete ossification, with the central portion of the lesion replaced by normal-appearing marrow fat. FOPD is histologically very similar to MO. The only difference is that the tumor of the digits tends to lack a clear-cut “zonation” pattern. The trabeculae of woven bone tend to be more dispersed throughout FOPD. FOPD tends to show extensive histologic and clinical overlap with bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation, also known as Nora’s lesion. Ancillary studies are of very little use in the diagnosis of MO. Instead, correlation with imaging features is key to making the correct diagnosis of MO. As mentioned earlier, the imaging appearance of MO is virtually pathognomonic. The failure or success of aspirating an MO depends on the thickness and integrity of the ossified periphery. Fine needle biopsy or aspiration is much more likely to yield diagnostic material if either the calcified rim can be successfully penetrated (usually under image guidance) or the shell is thin and incomplete. Successful aspirates are most likely to be composed of the contents of the interior of the lesion and to resemble the cytologic features of nodular fasciitis. Aspirates are most often modestly cellular and comprise individual single cells. Individual cells are usually spindled with abundant cytoplasm, reminiscent of the cellular features seen in association with cytologic repair. The background may have a granular or “dirty” texture with debris and inflammatory cells. Small fragments of entrapped muscle can often be identified in aspirates of MO and are a clue to the nature of the lesion (Figure 14.1.6). Of note, degenerating muscle fibers can display extreme cytologic atypia and should not be overinterpreted as malignant or “sarcomatous” elements. Osteoid is seldom aspirated or identified in cytologic examples of MO. Chondromyxoid matrix material, on the other hand, may occasionally be identified. FIGURE 14.1.1 A lesion similar to myositis ossificans (MO) occurs in the hand and is termed fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit. FIGURE 14.1.2 On imaging, MO often shows an incomplete rim of early calcification within the soft tissues. FIGURE 14.1.3 MO tends to show a “zonation” pattern with more mature bone at the periphery and immature elements in the center of the lesion. FIGURE 14.1.4 Fragments of skeletal muscle entrapped by encroaching ossification. FIGURE 14.1.5 In the central portion of MO, there is often a nodular fasciitis-like arrangement of plump myofibroblasts. In this example, there is early ossification. FIGURE 14.1.6 Aspirates of MO may have an alarming appearance. In this example, degenerating skeletal muscle is present in a background of plump epithelioid and spindled cells. 14.2 Phosphaturic Mesenchymal Tumor Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor (PMT) is an interesting, rare lesion, which may arise in either bone or soft tissue. PMT is also sometimes referred to as “PMT, mixed connective tissue variant.” It has an extremely heterogeneous appearance, and it should be suspected in an individual who presents with “oncogenic” or systemic osteomalacia and has a tumorous mass. The osteomalacia occurs as a result of the secretion of a phosphaturic hormone, fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) by the tumor cells. PMT tends to present in middle-aged adults, usually with a long history of vitamin D-resistant osteomalacia. Lab results include hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphaturia, normocalcemia, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase. FGF-23 appears to inhibit renal tubular phosphate transport. Interestingly, once the PMT is discovered and excised, the lab results normalize very quickly. Occasionally PMT will recur, as will the serum abnormalities and osteomalacia. The mass can be small and can be located in almost any location. About half of all cases are thought to originate within the bone. In the soft tissues, the extremities are a favored site. Because these lesions are sometimes very small, it is often necessary to “hunt” for them using radionucleotide scans. They do not tend to have any specific imaging features that are helpful in diagnosis. There are rare recorded cases of “malignant” PMT. The latter have both aggressive histologic features as well as an aggressive clinical course with multiple recurrences. As alluded to earlier, the histologic appearance of PMT is highly variable and will also depend, to some extent, on whether it is bone centered or soft tissue based. Bone-centered lesions can have numerous giant cells, areas of hemorrhage, and spindled cells (Figures 14.2.1 and 14.2.2). Hemosiderin-laden macrophages may be present in abundance. PMTs can easily be confused with giant cell tumor, nonossifying fibroma, or “brown tumor” of hyperparathyroidism (Figure 14.2.3). In addition, they can have variable amounts of intralesional matrix material, often in the form of irregular, “grungy,” or flocculent calcifications. True tumor-like (sarcomatous) osteoid is not identified. The background may be cellular and spindled or partially hyalinized. In soft tissue, PMTs may have a different appearance. In this location, there is usually a striking vascular pattern, usually with small capillary-like vessels, but occasionally containing hemangiopericytoma-like complex vascular spaces (Figure 14.2.4). Normal-appearing fat is often intimately associated with the tumor, a feature that may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of a lipoma or a liposarcoma variant (Figure 14.2.5). The main cell type is a small, plump, ovoid to spindle cell. These can be arranged in whorling patterns, simulating a myofibroma, or may be more widely dispersed in a chondromyxoid background (Figure 14.2.6). The soft tissue variant also frequently contains numerous osteoclast-type giant cells. Immunohistochemical staining for PMT is not particularly useful. Tumors often express smooth muscle actin, but are negative for desmin, S100 protein, and CD34.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Soft Tissue Tumors With Osseous or Cartilaginous Matrix