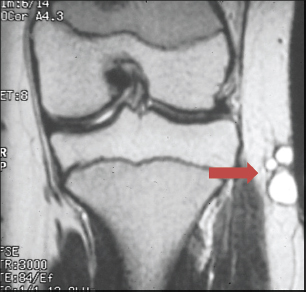

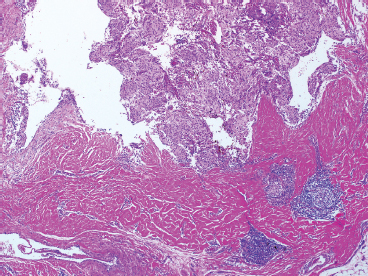

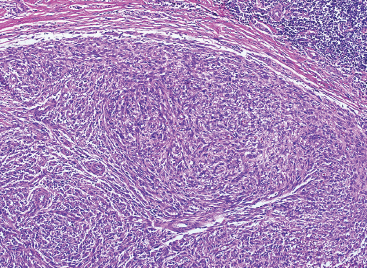

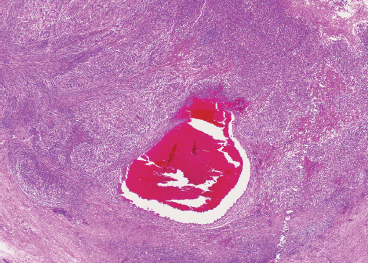

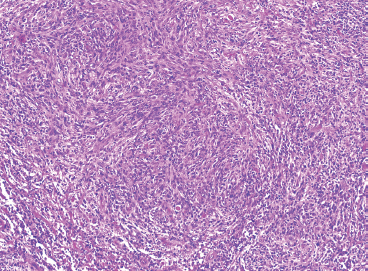

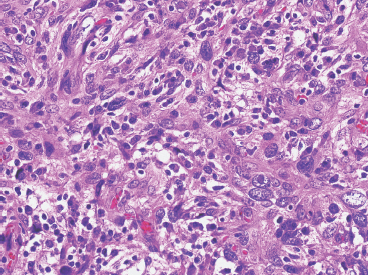

SOFT TISSUE TUMORS WITH INFLAMMATION 11.1 Angiomatoid Fibrous Histiocytoma 11.2 Myxoinflammatory Fibroblastic Sarcoma 11.3 Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor 11.1 Angiomatoid Fibrous Histiocytoma Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (AFH) is a rare tumor of uncertain differentiation that typically occurs in younger individuals, with a mean age of 20 years. Previously, this lesion had been classified as a variant (angiomatoid) of malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH). With the demise of the MFH category and the realization that this tumor seldom metastasizes distantly, it has been reclassified as a lesion of low to intermediate biologic potential. However, there are rare cases of AFH that have recurred and spread to regional lymph nodes. As such, this lesion is sometimes referred to as angiomatoid (malignant) fibrous histiocytoma by some. It is important that pathologists and clinicians alike recognize the ambiguity associated with this lesion and the alternative nomenclature. In addition, there is a tendency by some to confuse this lesion with the aneurysmal variant of fibrous histiocytoma that occurs in the skin. AFH most commonly presents as a small, firm lesion of the subcutaneous tissues (Figure 11.1.1). It tends to occur in sites that are associated with lymph nodes such as the supraclavicular and inguinal regions. In the extremities, it occurs in the popliteal and antecubital fossae. AFH rarely reaches a large size, most lesions measuring from 2 to 4 cm in diameter. More recently, cases of AFH have been described in unusual sites including bone, lung, and mediastinum. AFH is generally cystic and may or may not have a fibrous pseudocapsule associated with it (Figure 11.1.2). The pseudocapsule partially or completely surrounds the majority of the lesion, but there is often some cellular infiltration at the periphery of the lesion. This finding is important, as a favored treatment option is complete surgical removal of the lesion. The periphery of the lesion is also characterized by a heavy lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 11.1.3). Occasionally, the lymphoid infiltrate forms well-developed germinal centers, and the whole lesion can be mistaken for a lymph node. AFH tends to be centrally hemorrhagic and often contains a central blood-filled cystic cavity (Figure 11.1.4). The actual neoplastic cell of AFH is a histiocytoid or spindled cell with indistinct cytoplasmic borders. The spindled cells tend to aggregate in the center of the lesion and to arrange in various configurations: fascicles, whorls, and “storiform” patterns (Figure 11.1.5). Individual cells are usually small, but may often display striking nuclear pleomorphism, a feature that may lead to a misdiagnosis of a more malignant neoplasm (Figure 11.1.6). AFH may be a difficult lesion to diagnose, particularly if one is unfamiliar with its appearance. Because of the prominent lymphoid infiltrate and the presence of a secondary cellular component, AFH may be confused with a metastatic tumor to a lymph node. Fortunately, AFH is one of the many soft tissue tumors characterized by a recurrent chromosomal translocation, a feature that can be exploited for diagnostic purposes. Immunohistochemically, AFH tends to stain for desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD68. As mentioned previously, recurrent chromosomal translocations are identifiable in AFH. The most common translocation involves the EWSR1 gene locus with either the CREB1 or ATF1 gene. Another variant translocation involving FUS and ATF1 is present in a subset of AFH. As a result, lack of detection of a EWSR1 translocation by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe does not absolutely exclude a diagnosis of AFH. FISH for the FUS translocation should be attempted in EWSR1 FISH-negative lesions. Even then, a small subset of AFH will not be positive for either test, probably due to either cryptic rearrangements or variations that cannot be detected by commercially available FISH probe sets. Of interest, the most common translocation, t(2;22)(q33;q12) corresponding to transposition of the EWSR1 and CREB1 genes, is also identified in the rare clear cell sarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract. To date, relatively few case descriptions of the cytologic features of AFH have been documented in the literature. Aspirates of AFH have been described as “nondistinctive,” with cellular smears composed of ovoid to spindled histiocytic cells. Blood in the background may be identified, but sampling of the lymphocytic component is rare. FIGURE 11.1.1 Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (AFH) in the superficial soft tissues of the extremity (arrow). FIGURE 11.1.2 AFH is very frequently cystic. There may be a fibrous capsule surrounding the lesion. FIGURE 11.1.3 Heavy chronic inflammation is invariably present in association with AFH. In this example, the lymphoid infiltrate is present external to the fibrous pseudocapsule (in the upper right-hand corner). FIGURE 11.1.4 Focal areas of hemorrhage are frequently identified within the central portion of the lesion. This tends to simulate some of the other aneurysmal lesions of bone and soft tissue. Alternatively, the lesion may be mistaken for a hematoma. FIGURE 11.1.5 The interior of the lesion is composed of plump histiocytoid to spindled cells that are frequently arranged in a storiform pattern. FIGURE 11.1.6 There may be considerable nuclear atypia and pleomorphism associated with AFH. As such, this lesion is frequently confused with other types of high-grade malignancy. 11.2 Myxoinflammatory Fibroblastic Sarcoma Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma (MIFS) is a clinically distinctive lesion that is also known by several other names: inflammatory myxohyaline tumor of distal extremities with virocyte or Reed-Sternberg-like cells and acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma. Currently, the preferred nomenclature is MIFS, although this name overlaps somewhat with different entities, namely, myxofibrosarcoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Although the nomenclature may be confusing, MIFS represents a distinctive lesion of adults with a strong propensity to occur in the distal extremities, particularly in the hands and feet (Figure 11.2.1). Rare cases have been described in more proximal locations, notably the forearm, thigh, and the trunk. Patients are usually middle-aged adults, and there is an equal gender distribution. MIFS most often presents as an infiltrative, poorly defined superficial soft tissue lesion. It is often associated with pain, local tenderness, and swelling. Clinically and sometimes histologically, MIFS is often confused with a local inflammatory or infectious process. MIFS is a locally destructive lesion with a tendency to recur if not adequately excised. Despite frequent recurrence rates (up to 70%), MIFS does not metastasize widely. Very rare instances of metastases to regional lymph nodes have been described. MIFS are characterized cytogenetically by a translocation t(1;10)(p22;q24). This translocation has also been described in hemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumor (HFLT), leading some to speculate that these two entities represent different histologic variations of a continuous spectrum. Like MIFS, HFLT is a benign but locally infiltrative tumor. It tends to occur in the ankle region of older adult women. Histologically, HFLT tends to have a more prominent lipomatous component than MIFS. MIFS is a poorly circumscribed, locally infiltrative tumor with a vague nodular configuration. Individual tumor nodules are comprised of variably myxoid stroma with a prominent spindle cell and inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 11.2.2). There may be considerable variation from one nodule to the next in overall cellularity, but myxoid stroma should be a prominent feature. Some areas within the tumor may show focal hyalinization. There is also an irregularly distributed but nevertheless prominent inflammatory component. This is comprised of a mixture of neutrophils and eosinophils as well as plasma cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes. The spindle cell component of MIFS often shows moderate nuclear pleomorphism, and atypia and mitoses can easily be identified. One very striking feature of MIFS is the presence of numerous intranuclear cytoplasmic invaginations, reminiscent of the appearance of virally infected cells (Figure 11.2.3). In addition, some tumoral cells often have macronucleoli, a feature that mimics the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin disease (Figure 11.2.4). Another prominent feature is the presence of pseudolipoblasts within the zones of myxoid stroma (Figure 11.2.5). Variable features include small foci of necrosis and hemosiderin deposition (Figure 11.2.6). Occasionally there may be prominent vessels, and inflammatory cells that have a tendency to aggregate around them in the more myxoid foci of MIFS. As with other myxoid tumors, immunohistochemistry is not very useful in the diagnosis of MIFS. There can be nonspecific staining for a variety of markers including vimentin and CD68. Of note, the Reed-Sternberg-like cells do not stain for CD15 or CD30. To date, the presence of the t(1;10) translocation has not been widely exploited for diagnostic purposes.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Soft Tissue Tumors With Inflammation