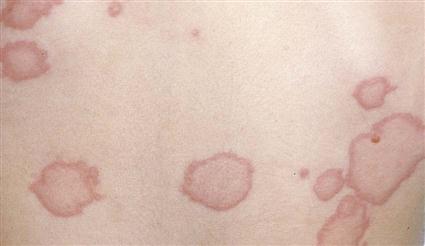

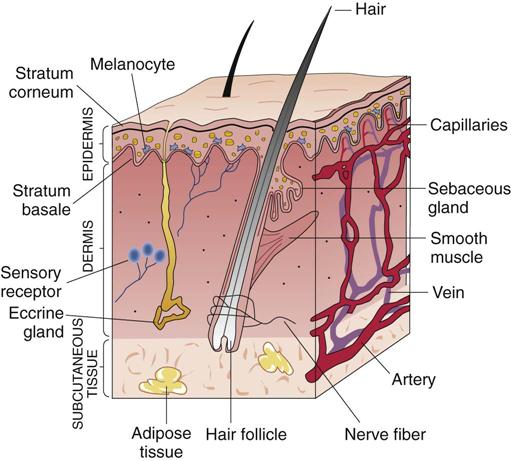

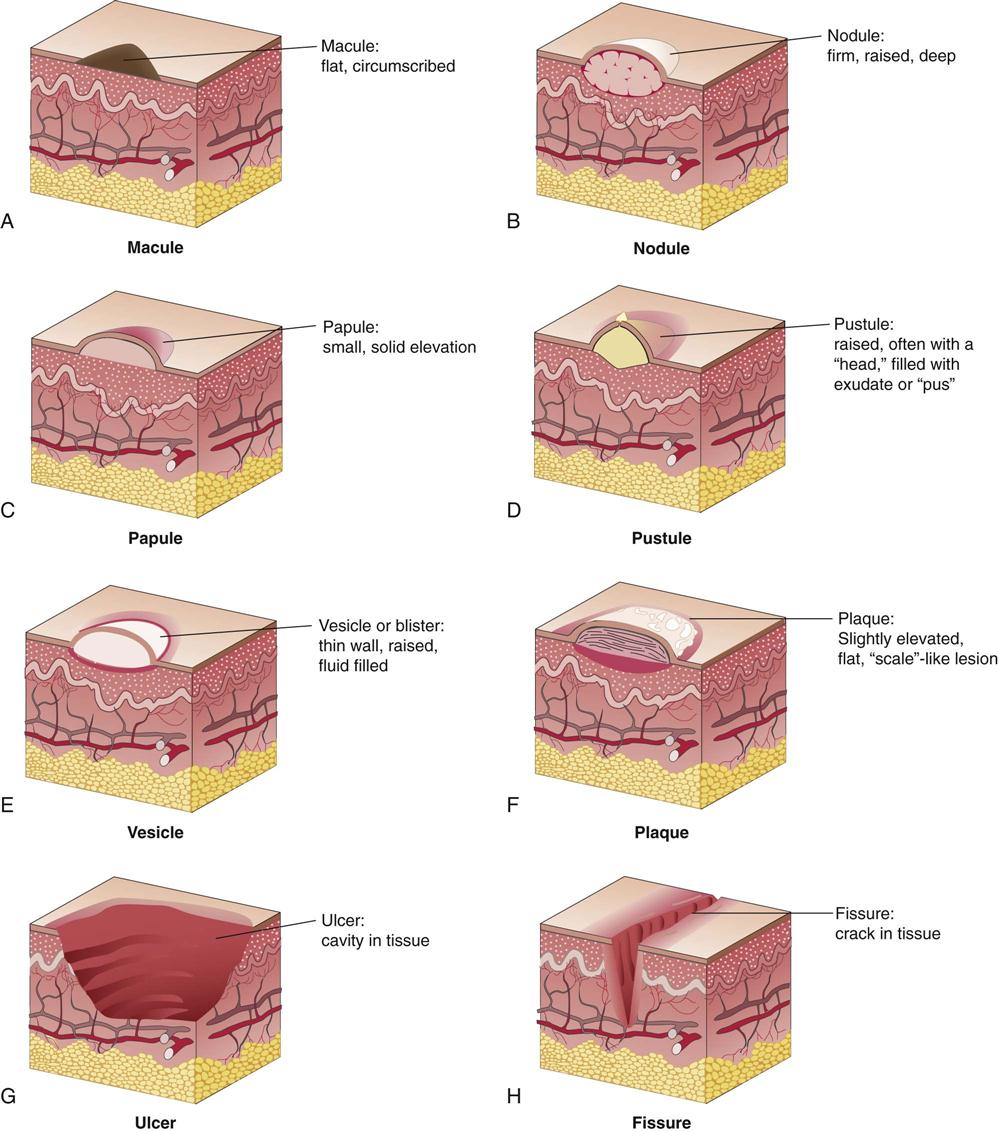

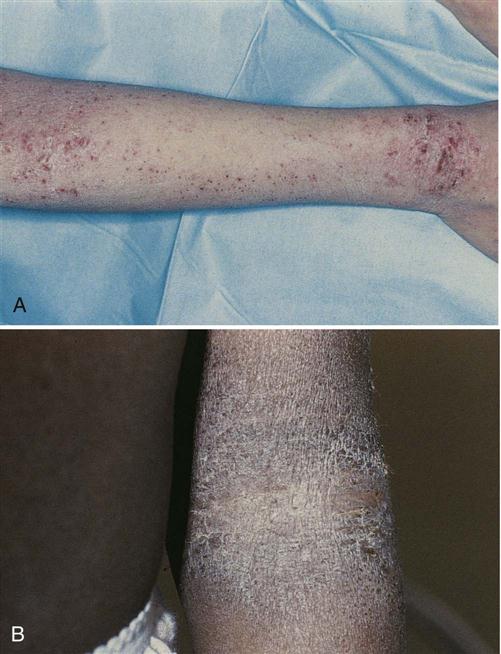

After studying this chapter, the student is expected to: 1. Describe common skin lesions. 4. Distinguish between the bacterial infections impetigo and furuncles. 5. Describe the effects of Streptococcus pyogenes on connective tissue in acute necrotizing fasciitis. 6. Describe the affects and treatment of leprosy. 7. Describe the viral infections herpes simplex and warts. 8. Describe the forms of tinea, a fungal infection. 9. Describe the agent, the infection, and manifestations of scabies and pediculosis. albinism atopic autoinoculation denuded excoriations keratin larvae lichenification sebum As the largest organ in the body, the skin plays significant roles in both the function of the body physically and in how we are perceived in society. The skin, or integument, consists of two layers, the epidermis and the underlying dermis, along with their associated appendages, such as hair follicles and glands (Fig. 8-1). The epidermis consists of five layers, which vary in thickness at different areas of the body. For example, facial skin is relatively thin, but the soles are protected by a thick layer of skin (primarily stratum corneum). There are no blood vessels or nerves in the epidermis. Nutrients and fluid diffuse into it from blood vessels located in the dermis. The innermost layer of the epidermis is the stratum basale, located on the basement membrane. New squamous epithelial cells form by mitosis in the stratum basale (the only layer of the epidermis where mitosis occurs), and one of each pair of cells then moves upward, forming, in turn, the stratum spinosum, the stratum granulosum, and the stratum lucidum (which is present primarily in thick skin), eventually being shed from the outer layer, the stratum corneum. Although these cells are in the stratum granulosum, keratin, a protein found in skin, hair, and nails, is deposited in them. Keratin prevents both loss of body fluid through the skin and entry of excessive water into the body, as when swimming. The epithelial cells become flatter as they progress upward away from the dermis, and they eventually die from lack of nutrients. Thus, the stratum corneum, the top or outer layer of the epidermis, consists of many layers of dead, flat, keratinized cells that are constantly sloughed from the surface a few weeks after being formed in the basal layer. The epidermis also contains melanocytes, specialized pigment-producing cells. The amount of melanin, or dark pigment, produced by these cells determines skin color. Melanin production depends on multiple genes as well as environmental factors such as sun exposure (ultraviolet light). African Americans rarely develop skin cancer as a result of ultraviolet light exposure because of increased melanin in the skin, which acts as a protection from the sun’s rays. Albinism results from a recessive trait leading to a lack of melanin production. A person with this trait has white skin and hair and lacks pigment in the iris of the eye. This individual must avoid exposure to the sun. Vitiligo refers to small areas of hypopigmentation which may gradually spread to involve larger areas. Melasma, or chloasma, refers to patches of darker skin, often on the face, that may develop during pregnancy. An additional pigment, carotene, gives a yellow color to the skin. Pink tones in the skin are increased with additional vascularity or blood flow in the dermis. The dermis is a thick layer of connective tissue that includes elastic and collagen fibers and varies in thickness over the body. These constituents provide both flexibility and strength in the skin and support for the nerves and blood vessels passing through the dermis. Many sensory receptors for pressure or texture, pain, heat, or cold are found in the dermis. The junction of the dermis with the epidermis is marked by papillae, irregular projections of dermis into the epidermal region. More capillaries are located in the papillae to facilitate diffusion of nutrients into the epidermis. Blood flow is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system. Embedded in the skin are the appendages, or accessory structures—the hair follicles, sweat and sebaceous glands, and nails. The secretion, sweat or perspiration, is odorless when formed, but bacterial action by normal flora on the constituents of sweat often causes odor to develop. Beneath the dermis is the subcutaneous tissue or hypodermis, which consists of connective tissue, fat cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, blood vessels, nerves, and the base of many of the appendages. A complex mix of resident (normal) flora is present on the skin, and the components differ in various body areas (see Chapter 6). Microbes residing under the fingernails may infect inflammatory lesions or breaks in the skin, particularly when one scratches the skin. Microbes, primarily bacteria and fungi, are also present deep in the hair follicles and glands of the skin and may be a source of opportunistic infections when there is injury such as burns (see section on burns in Chapter 5) or other inflammatory lesion. Infection may spread systemically from skin lesions. The skin is prone to damage as it is in constant contact with the external environment which includes such threats as toxic chemicals, direct trauma, or animal bites/stings. Systemic disorders additionally may affect the skin. Also, the skin changes with aging, showing loss of elasticity, thinning, and loss of subcutaneous tissue (see Chapter 24). Minor abrasions or cuts of the skin heal quickly with mitosis of the epithelial cells (see Chapter 5 for the healing process). When large areas of the skin are damaged, appendages may be lost, function impaired, and fibrous scar tissue forms, often restricting mobility of joints. See the discussion on burns in Chapter 5 for information on biosynthetic wound coverings or “artificial skin,” useful when large areas of skin are damaged. The characteristics of skin lesions are frequently helpful in making a diagnosis. Skin lesions may be caused by systemic disorders such as liver disease, systemic infections such as chickenpox (typical rash), or allergies to ingested food or drugs, as well as by localized factors such as exposure to toxins. Common types of lesions are illustrated in Figure 8-2 and defined in Table 8-1. The location, length of time the lesion has been present, and any changes occurring over time are significant. Physical appearance, including color, elevation, texture, type of exudate, and the presence of pain or pruritus (itching) are also important considerations. Some lesions, such as tumors, usually are neither painful nor pruritic and therefore may not be noticed. A few skin disorders, such as herpes, cause painful lesions. TABLE 8-1 Description of Some Skin Lesions Pruritus is associated with allergic responses, chemical irritation due to insect bites, or infestations by parasites such as scabies mites. The mechanisms producing pruritus are not totally understood. It is known that release of histamine in a hypersensitivity response causes marked pruritus (see Chapter 7). Pruritus also may result from mild stimulation of pain receptors by irritants. The most common manifestations include redness, and itchiness. Scratching a pruritic area usually increases the inflammation and may lead to secondary infection. Infection results from breaking the skin barrier, thus allowing microbes on the fingers (under the nails) or on the surrounding skin to invade the area. Infection may then produce scar tissue in the area. Bacterial infections may require culture and staining of specimens for identification. Skin scrapings for microscopic examination, sample culturing, direct observation of the infected area and other specific procedures (e.g., ultraviolet light, Wood’s lamp) are necessary to detect fungal or parasitic infections. Biopsy is an important procedure in the detection of malignant changes in tissue and provides a safeguard prior to or following removal of any skin lesion. Blood tests may be helpful in the diagnosis of conditions due to allergy or abnormal immune reactions. Patch or scratch tests are used to screen for allergens and may be followed up by diet restrictions to identify specific food allergens. Drug reactions are assessed utilizing specific antigen–antibody testing. Pruritus may be treated by antihistamines or glucocorticoids, administered topically or orally. Identification and avoidance of allergens reduce the risk of recurrence. With many skin disorders, extremes of heat or cold and contact with certain rough materials such as wool aggravate the skin lesions. Soaks or compresses using solutions such as Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate) or colloidal oatmeal (Aveeno) may cool the skin and reduce itching. Some topical skin preparations contain a local anesthetic to reduce itching and burning sensations. Infections may require appropriate topical antimicrobial treatment. If the infection is severe, systemic medication may be preferred. Precancerous lesions may be removed, by surgery, laser therapy, electrodesiccation (heat), or cryosurgery (e.g., freezing by liquid nitrogen). There are a large number of skin disorders. Only a small number of representative dermatologic conditions are included here. Burns cause an acute inflammatory response. This topic is covered in Chapter 5 along with the processes of healing. Contact dermatitis may be caused by exposure to an allergen or by direct chemical or mechanical irritation of the skin. Allergic dermatitis may result from exposure to any of a multitude of substances, including metals, cosmetics, soaps, chemicals, and plants. Sensitization occurs on the first exposure (type IV cell-mediated hypersensitivity—see Chapter 7), and on subsequent exposures, manifestations such as a pruritic rash develop at the site a few hours after exposure to that allergen. The location of the lesions is usually a clue to the identity of the allergen (Fig. 8-3). For example, poison ivy may cause lesions, often linear, on the ankles or hands, or a necklace may cause a rash around the neck. Typical allergic dermatitis is indicated by a pruritic, erythematous, and edematous area, which is often covered with small vesicles. Direct chemical irritation does not involve an immune response but is an inflammatory response caused by direct exposure to substances such as soaps and cleaning materials, acids, or insecticides. The skin is usually red and edematous and may be pruritic or painful. Removal of the irritant as soon as possible and reduction of the inflammation with topical glucocorticoids are usually effective treatment. Urticaria (hives) results from a type I hypersensitivity reaction, commonly caused by ingested substances such as shellfish or certain fruits or drugs. The subsequent release of histamine causes the eruption of hard, raised erythematous lesions on the skin, often scattered all over the body (Fig. 8-4). The lesions are highly pruritic. Occasionally hives also develop in the pharyngeal mucosa and may obstruct the airway, causing difficulty with breathing. In this case, medical assistance should be sought as quickly as possible. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) is a common problem in infancy and may persist into adulthood in some persons. Atopic refers to an inherited tendency toward allergic conditions. Frequently the family history includes individuals with eczema, allergic rhinitis or hay fever, and asthma, indicating a genetic component. Chronic inflammation results from the response to allergens (Fig. 8-5). Eosinophilia and increased serum IgE levels indicate the allergenic basis for atopic dermatitis (type I hypersensitivity).

Skin Disorders

Learning Objectives

Key Terms

Review of the Skin

Skin Lesions

Macule

Small, flat, circumscribed lesion of a different color than the normal skin

Papule

Small, firm, elevated lesion

Nodule

Palpable elevated lesion; varies in size

Pustule

Elevated, erythematous lesion, usually containing purulent exudate

Vesicle

Elevated, thin-walled lesion containing clear fluid (blister)

Plaque

Large, slightly elevated lesion with flat surface, often topped by scale

Crust

Dry, rough surface or dried exudate or blood

Lichenification

Thick, dry, rough surface (leather-like)

Keloid

Raised, irregular, and increasing mass of collagen resulting from excessive scar tissue formation

Fissure

Small, deep, linear crack or tear in skin

Ulcer

Cavity with loss of tissue from the epidermis and dermis, often weeping or bleeding

Erosion

Shallow, moist cavity in epidermis

Comedone

Mass of sebum, keratin, and debris blocking the opening of a hair follicle

Diagnostic Tests

General Treatment Measures

Inflammatory Disorders

Contact Dermatitis

Urticaria

Atopic Dermatitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine