Chapter 24 Skin disease

Structure and function of the skin

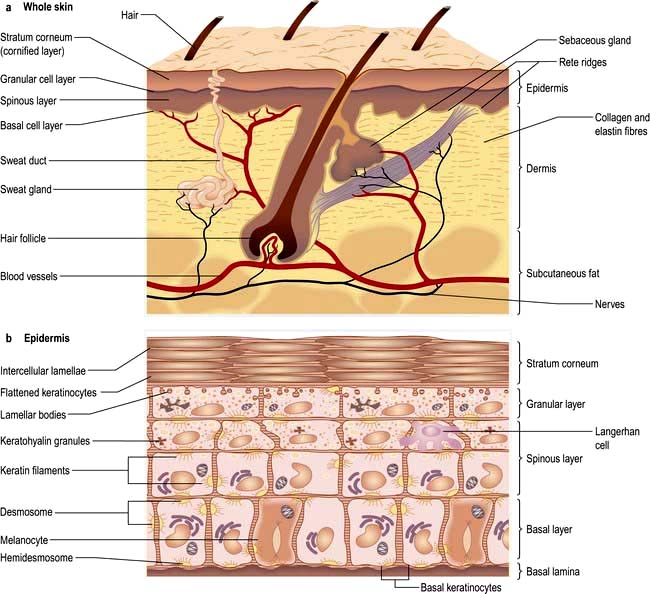

The skin consists of four distinct layers:

The functions of the skin are summarized in Box 24.1.

![]() Box 24.1

Box 24.1

Functions of the skin

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

Antigen presentation/immunological reactions/wound healing

Antigen presentation/immunological reactions/wound healing

Basement membrane zone

The basement membrane zone (see Fig. 24.27) is a complex proteinaceous structure consisting of type IV, VII and XVII collagen, hemidesmosomal proteins, integrins and laminin. Collectively, they hold the skin together, keeping the epidermis firmly attached to the dermis. Inherited or autoimmune-induced deficiencies of these proteins can cause skin fragility and a variety of blistering diseases (see p. 1221).

The dermis

The sweat glands

Eccrine sweat glands are found throughout the skin except the mucosal surfaces.

The sweat glands and vasculature are involved in temperature control.

Hair

Terminal: medullated coarse hair, e.g. scalp, beard, pubic

Terminal: medullated coarse hair, e.g. scalp, beard, pubic

Vellus: non-medullated fine downy hairs seen on the face of women and in prepubertal children

Vellus: non-medullated fine downy hairs seen on the face of women and in prepubertal children

Lanugo: non-medullated soft hair on newborns (most marked in premature babies) and occasionally in people with anorexia nervosa.

Lanugo: non-medullated soft hair on newborns (most marked in premature babies) and occasionally in people with anorexia nervosa.

The subcutaneous layer

FURTHER READING

Borkowski AW, Gallo RL. The coordinated response of the physical and antimicrobial peptide barriers of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:285–287.

Lin JY, Fisher DE. Melanocyte biology and skin pigmentation. Nature 2007; 445:843–850.

Shimomura Y, Christiano AM. Biology and genetics of hair. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2010; 11:109–132.

Approach to the patient

The history should aim to elicit the following points:

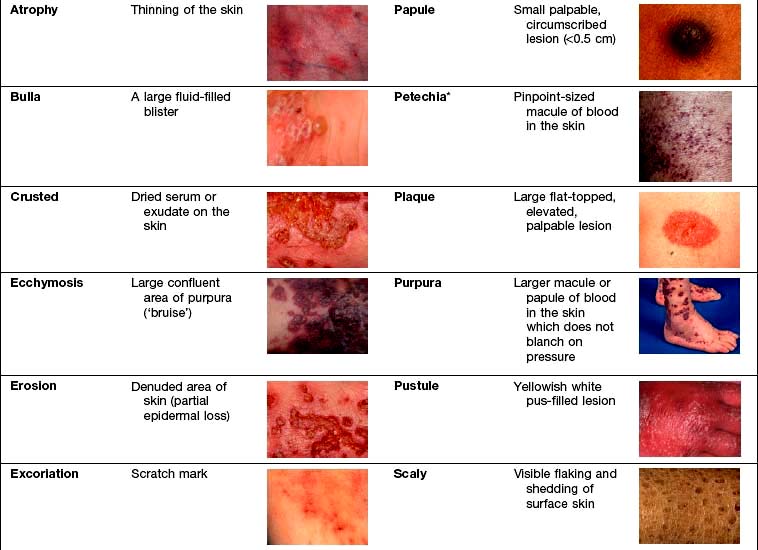

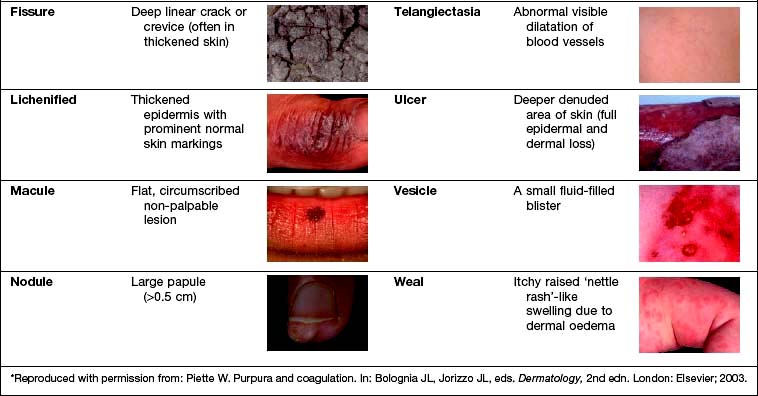

Examination entails looking and feeling a rash (for terminology, see Table 24.1). It should include an assessment of nails, hair and mucosal surfaces even if these are recorded as unaffected. The following terms are used to describe distribution: flexural, extensor, acral (hands and feet), symmetrical, localized, widespread, facial, unilateral, linear, centripetal (trunk more than limbs), annular and reticulate (lacey network or mesh like).

Investigation. With regard to investigation, clinical acumen remains the most useful tool in dermatology but a variety of tests are useful in confirming a diagnosis (Table 24.2).

Table 24.2 Investigations used in skin disorders

| Test | Use | Clinical example |

|---|---|---|

Skin swabs | Bacterial culture | Impetigo |

Blister fluid | Electron microscopy, viral culture and PCR | Herpes simplex |

Skin scrapes | Fungal culture | Tinea pedis |

Microscopy | Scabies | |

Nail sampling | Fungal culture | Onychomycosis |

Wood’s light | Fungal fluorescence | Scalp ringworm |

Erythrasma | ||

Blood tests | Serology | Streptococcal cellulitis |

Autoantibodies | Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

HLA typing | Dermatitis herpetiformis | |

DNA analysis | Epidermolysis bullosa | |

Skin biopsy | Histology | General diagnosis |

Immunohistochemistry | Cutaneous lymphoma | |

Immunofluorescence | Immunobullous disease | |

Culture | Mycobacteria/fungi | |

Patch tests | Allergic contact eczema | Hand eczema |

Urine | Dipstick (glucose) | Diabetes mellitus |

Cytology (red cells) | Vasculitis | |

Dermatoscopy (direct microscopy of skin) | Assessment of pigmented lesions | Malignant melanoma |

Infections

Bacterial infections (see also p. 114)

Impetigo

Impetigo is a highly infectious skin disease most common in children (Fig. 24.2). It presents as weeping, exudative areas with a typical honey-coloured crust on the surface. It is spread by direct contact. The term ‘scrum pox’ refers to impetigo spread between rugby players. Staphylococci or group A β-haemolytic streptococci are the causative agents: skin swabs should be taken.

Treatment

Impetigo is usually treated with oral antibiotics for 7–10 days (flucloxacillin 500 mg four times daily for Staphylococcus; phenoxymethylpenicillin 500 mg four times daily for Streptococcus). Other close contacts should be examined and children should avoid school for 1 week after starting therapy. If impetigo appears resistant to treatment or recurrent, take nasal swabs and check other family members. Nasal mupirocin (three times daily for 1 week) is useful to eradicate nasal carriage, especially in hospital staff. Community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4) is increasingly recognized as a cause of superficial skin infections and treatment should be governed by bacterial sensitivities.

Bullous impetigo/staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Rarely Staphylococcus releases an exfoliating toxin which acts high up in the epidermis: toxin A causes blistering at the site of infection (bullous impetigo), toxin B spreads through the body causing more widespread blistering (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, SSSS). The latter is more common in childhood with very low mortality rates. In adults it is often associated with renal disease or immunosuppression, and mortality rates increase to 50%. Both these toxins cleave desmoglein 1 (a desmosomal protein) so mucosal involvement does not occur (this is analogous to pemphigus foliaceous which has the same target antigen, p. 1222).

SSSS can mimic toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN, see p. 1231). It can be differentiated in two ways: mucosal involvement only occurs in TEN, and skin biopsy shows a more superficial split in SSSS (intraepidermal) than in TEN (subepidermal). Both bullous impetigo and SSSS are treated with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (e.g. flucloxacillin) and supportive care.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis presents as a hot, sometimes tender area of confluent erythema of the skin due to infection of the deep subcutaneous layer. It often affects the lower leg, causing an upward-spreading, hot erythema, and occasionally will blister, especially if oedema is prominent. It may also be seen affecting one side of the face. Patients are often unwell with a high temperature. It is usually caused by a β-haemolytic streptococcus, rarely a staphylococcus, and sometimes community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4). In the immunosuppressed or diabetic patient Gram-negative organisms or anaerobes should be suspected.

Necrotizing fasciitis (see p. 116).

Erythrasma

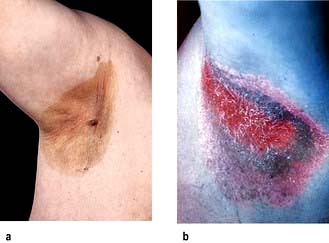

Erythrasma is caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum. It usually presents as an orange-brown flexural rash, and is often seen in the axillae or toe web spaces (Fig. 24.3). It is frequently misdiagnosed as a fungal infection. The rash shows a dramatic coral pink fluorescence under Wood’s (ultraviolet) light.

Treatment is with oral erythromycin 500 mg four times daily for 7–10 days.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Treatment is difficult but weight loss, ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics, oral retinoids, zinc and co-cyprindiol (2 mg cyproterone acetate + 35 µg ethinylestradiol in females only) have been tried. They should be used as for acne vulgaris (p. 1212). Severe recalcitrant cases have been treated with intravenous infliximab, a monoclonal antibody (p. 72). Surgery and skin grafting is sometimes required.

Mycobacterial infections

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) (p. 130)

Tuberculoid leprosy presents with a few larger, hypopigmented (see Fig. 4.28) or erythematous plaques with an active erythematous, often raised, rim. Lesions are usually markedly anaesthetic, dry and hairless, reflecting the nerve damage. Nerves may be enlarged and palpable. Biopsy shows a granulomatous infiltrate centred on nerves but no organisms.

Skin manifestations of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can occasionally cause skin manifestations:

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

Viral infections

Viral exanthem

This is the commonest type of virus-induced rash and presents clinically as a widespread nonspecific erythematous maculopapular rash. It probably arises due to circulating immune complexes of antibody and viral antigen localizing to dermal blood vessels. The rash can be caused by many different viruses (e.g. echovirus, erythrovirus, human herpes virus-6, Epstein–Barr virus; see chapter 4) and so is rarely diagnostic. The rash will resolve spontaneously in 7–10 days.

Herpes simplex virus (see also p. 97)

HSV type 2 infections are discussed on page 97. Other rare complications of HSV infection include corneal ulceration, eczema herpeticum, chronic perianal ulceration in AIDS patients and erythema multiforme.

Varicella zoster virus

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes the common childhood infection called chickenpox. It is discussed on page 98. It also causes herpes zoster.

Herpes zoster (shingles)

‘Shingles’ results from a reactivation of VZV. It may be preceded by a prodromal phase of tingling or pain, which is then followed by a painful and tender blistering eruption in a dermatomal distribution (Fig. 24.4 and Fig. 4.15, p. 98). The blisters occur in crops, may become pustular and then crust over. The rash lasts 2–4 weeks and is usually more severe in the elderly. Occasionally more than one dermatome is involved.

Human papilloma virus

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is responsible for the common cutaneous infection of ‘viral warts’.

Common warts are papular lesions with a coarse roughened surface, often seen on the hands and feet, but also on other sites. Small black dots (bleeding points) are often seen within the lesion (Fig. 24.5). If they occur on the face they are often elongated (‘filiform’) Children and adolescents are usually affected. Spread is by direct contact and is also associated with trauma.

Molluscum contagiosum (‘water blisters’)

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection of childhood caused by the pox virus. Clinically, lesions are multiple small (1–3 mm) translucent papules which often look like fluid-filled vesicles but are in fact solid. Individual lesions may have a central depression called a punctum. They exhibit the Köbner phenomenon (p. 1208). They can occur at any body site including the genitalia. Transmission is by direct contact. Occasionally lesions may be up to 1 cm in diameter (‘giant molluscum’).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree