77

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

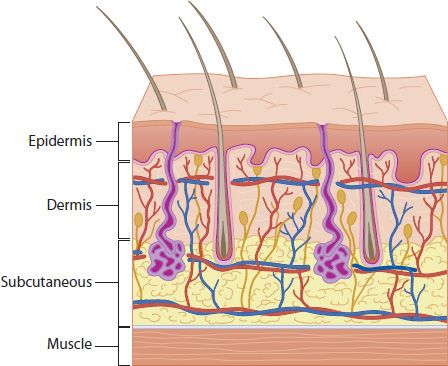

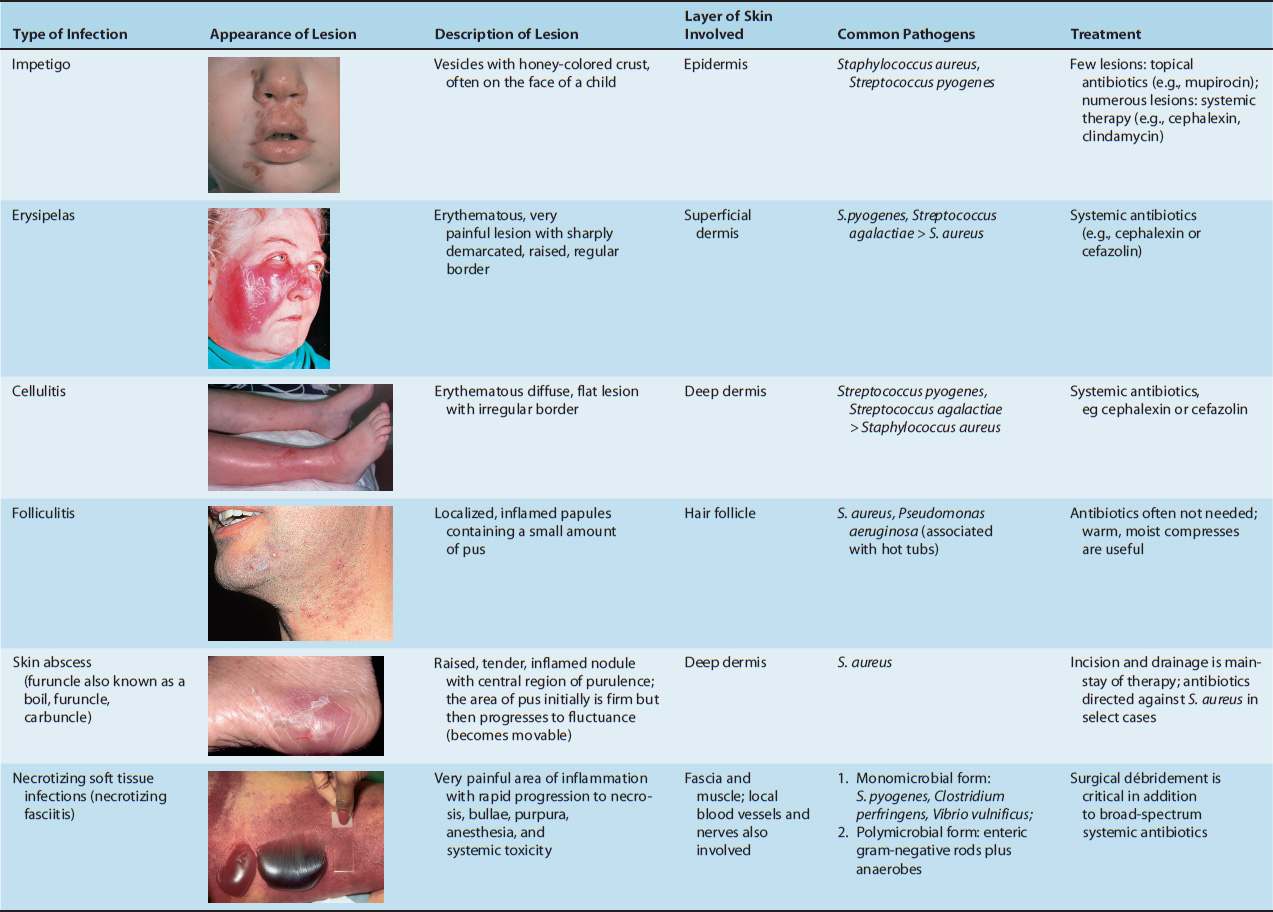

Skin and soft tissue infections are some of the most common infectious diagnoses and result in hundreds of thousands of medical office and emergency room visits each year. These infections often occur following a break in normal skin integrity from either trauma or skin disease (e.g., atopic dermatitis). The vast majority of these infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (Table 77–1). Hematogenous seeding of organisms into the skin can occur but is uncommon. Normal histology of the skin can be seen in Figure 77–1.

FIGURE 77-1 Layers of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Note sebaceous glands (purple) and hair follicles with protruding hair. (Courtesy of Mary Simmons, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Bio-Medical Communications Department.)

TABLE 77-1 Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: Appearance of Lesions, Skin Layers Involved, Common Pathogens, and Treatment Modalities

IMPETIGO

Definition

Impetigo is an infection of the epidermal layer of skin.

Pathophysiology

There are two modes of acquisition of impetigo, primary infection that occurs in otherwise normal skin or secondary impetigo, which occurs following a break in normal skin integrity. Bacteria invade into the epidermal layer and cause local damage. Bullous impetigo occurs when strains of S. aureus secrete exfoliative toxin, a protease that degrades desmoglein, resulting in loss of adhesion of the superficial epidermis. This is the same toxin that causes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Clinical Manifestations

There are three clinical variants of impetigo: (1) classic impetigo, (2) bullous impetigo, and (3) ecthyma. Classic impetigo begins as papules that progress to vesicles surrounded by erythema. Subsequently, the fluid-filled lesions enlarge and break down to form thick, adherent crusts with a characteristic golden “honey-colored” appearance (Figure 77–2). Bullous impetigo is similar to classic impetigo, but bullae form (Figure 77–3) via the mechanism described earlier. Ecthyma is an ulcerating form of impetigo where the lesion penetrates through the epidermis into the dermis (Figure 77–4). Some strains of S. pyogenes that cause impetigo have been associated with poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, and providers should be aware of this potential complication. Rheumatic fever is a less common sequel to streptococcal skin infections.

FIGURE 77–2 Classic nonbullous impetigo. Note lesions with a “honey-colored” crust around the nose and mouth. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson R (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

FIGURE 77-3 Bullous impetigo. Note bullous lesion (arrow). (Used with permission from Ma OJ, Cline DM, Tintinalli JE, et al. Emergency Medicine Manual. 6th ed. © 2004, McGraw-Hill, New York.)

FIGURE 77-4 Ecthyma. Note necrotic lesion on the nose. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson R (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

Pathogens

S. aureus and S. pyogenes are the two main pathogens that cause impetigo. In neutropenic patients, a clinical syndrome termed ecthyma gangrenosum is due to disseminated Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Its cutaneous findings are a result of hematogenous seeding of dermal vessels with bacteria, resulting in thrombosis, ischemia, and focal skin necrosis. This is not a superficial skin infection.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of impetigo is made clinically in most cases. Culture of bullous fluid or pus can be considered when patients do not respond to standard treatment.

Treatment

Antibacterial therapy should be directed against both S. aureus and S. pyogenes. Topical therapy with mupirocin or retapamulin is preferred when only a few lesions are present. In patients with widespread disease, a systemic antimicrobial is preferred. If concern for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) exists, clindamycin is recommended; otherwise, cephalexin or dicloxacillin would be appropriate.

Prevention

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree