Patient Story

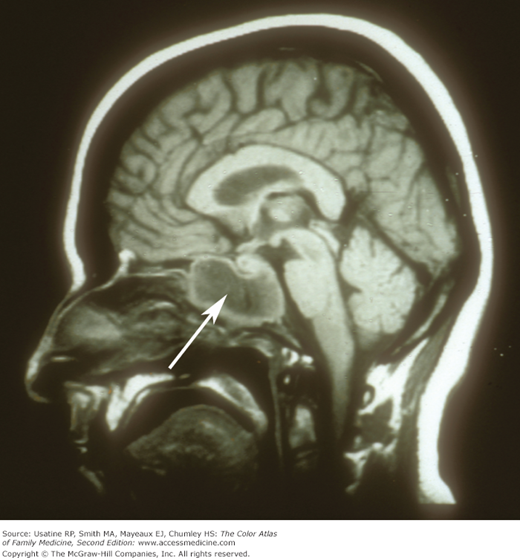

A 55-year-old woman complains of sinus pressure for the past 2 weeks along with headache, rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, and cough. This all started with a cold 3 weeks ago. She has chronic allergic rhinitis, but now the pressure on the right side of her face has become intense and her right upper molars are painful. The nasal discharge has become discolored and she feels feverish. She is diagnosed clinically with right maxillary sinusitis and is prescribed an antibiotic. Two weeks later when her symptoms have persisted, a CT is ordered and she is found to have air-fluid levels in both maxillary sinuses and loculated fluid on the right side. (Figures 31-1 and 31-2.) The antibiotic is changed to amoxicillin/clavulanate and she is given information about nasal saline irrigation for symptom relief. If the symptoms don’t improve the clinician plans to send her to ENT for further evaluation.

Introduction

Rhinosinusitis is symptomatic inflammation of the sinuses, nasal cavity, and their epithelial lining.1 Mucosal edema blocks mucous drainage, creating a culture medium for viruses and bacteria. Rhinosinusitis is classified by duration as acute (<4 weeks), subacute (4 to 12 weeks), or chronic (>12 weeks).

Epidemiology

- Rhinosinusitis is common in the United States, with an estimated prevalence of 14% to 16% of the adult population annually.1,2 The prevalence is increased in women and in individuals living in the southern United States.

- Only one-third to one-half of primary care patients with symptoms of sinusitis actually have bacterial infection.3

- Sinusitis is the fifth-leading diagnosis for which antibiotics are prescribed in the United States.1

- Children average 6 to 8 colds per year. Of those, 0.5% to 8% will develop a sinus infection.4,5

- This problem is responsible for millions of office visits to primary care physicians each year.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Sinus cavities are lined with mucous-secreting respiratory epithelium. The mucus is transported by ciliary action through the sinus ostia (openings) to the nasal cavity. Under normal conditions, the paranasal sinuses are sterile cavities and there is no mucous retention.

- Bacterial sinusitis occurs when ostia become obstructed or ciliary action is impaired, causing mucus accumulation and secondary bacterial overgrowth.

- The causes of sinusitis include:6

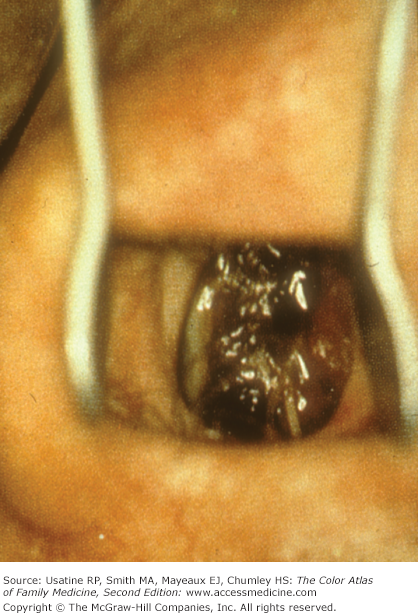

- Infection – most commonly viral (e.g., rhinovirus, parainfluenza, and influenza) followed by bacteria infection (e.g., community-acquired acute cases – about half from S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae followed by Moraxella catarrhalis). In immunocompromised patients, fulminant fungal sinusitis may occur (e.g., rhinocerebral mucormycosis – Figure 31-3).

- Noninfectious obstruction—Allergic, polyposis, barotrauma (e.g., deep-sea diving, airplane travel), chemical irritants, tumors (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, granulomatous disease, inverting papilloma), and conditions that alter mucous composition (e.g., cystic fibrosis).

- Infection – most commonly viral (e.g., rhinovirus, parainfluenza, and influenza) followed by bacteria infection (e.g., community-acquired acute cases – about half from S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae followed by Moraxella catarrhalis). In immunocompromised patients, fulminant fungal sinusitis may occur (e.g., rhinocerebral mucormycosis – Figure 31-3).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the clinical picture with typical symptoms listed below. Symptoms arising from viral infection generally peak by day 5 or before. Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis is diagnosed when symptoms are present for 10 days or longer or when symptoms worsen after initial stability or improvement (“double worsening” or “double sickening”); it can also be presumed in patients with unusually severe presentations or extrasinus manifestations of infection.1 Superimposed bacterial infection is estimated to occur in 0.5% to 2% of cases of viral rhinosinusitis.1

- Most cases are seen in conjunction with viral upper respiratory infections and represent sinus inflammation rather than infection.3

- Nonspecific symptoms include cough, sneezing, fever, nasal discharge (may be purulent or discolored), congestion, and headache.

- The American Academy of Otolaryngology guideline and the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps recommend a diagnosis of rhinosinusitis with a combination (2 or more) of purulent nasal drainage associated with nasal obstruction, facial pain-pressure-fullness, or both; the latter also recognizes reduction/loss of smell as a cardinal feature.1,7 There are no prospective trials that validate this approach.

- Other localizing symptoms include facial pain or pressure over the involved sinus when bending over or supine (i.e., forehead in frontal sinusitis, cheek with maxillary sinusitis, between the eyes with ethmoid sinusitis, and neck and top of the head with sphenoid sinusitis) and maxillary tooth pain, most commonly the upper molars; the latter is seen more often with bacterial sinusitis. Halitosis is also attributed to bacterial causes.

- In a study of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, diagnosis based on symptoms was problematic and only dysosmia (impairment in the sense of smell) and the presence of polyps could distinguish between normal and abnormal radiographs.8

- Most sinus infections involve the maxillary sinus followed in frequency by the ethmoid (anterior), frontal, and sphenoid sinuses; however, most cases involve more than one sinus.5

- Children are more likely to have inflammation in the posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses.9

- Culture of nasal or nasopharyngeal secretions is not recommended as these have not been shown to differentiate between bacterial and viral rhinosinusitis.1

- If culture is needed because of suspected bacterial resistance or persistence of infection, a recent metaanalysis found endoscopically directed middle meatal cultures to be reasonably sensitive (80.9%), specific (90.5%), and accurate (87.0%; 95% confidence interval, 81.3% to 92.8%) compared with maxillary sinus taps.10

- Radiography should not be obtained for patients meeting diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, unless a complication or alternate diagnosis is suspected.1 If performed in cases of clinical uncertainty or for complications (e.g., orbital, intracranial, or soft-tissue involvement), plain sinus radiography is considered positive for acute sinusitis with the presence of air-fluid level, complete opacification, or at least 6 mm of mucosal thickening; it has a reported sensitivity of 76% and specificity 79%.11 There are considerable limitations to the sensitivity of plain films, especially in diagnosing ethmoid and sphenoid disease.

- For children, ultrasound compared favorably to plain film for suspected maxillary sinusitis (94.9% sensitivity, 98.4% specificity).12

- Nasal endoscopy, identifying purulent material within the drainage area of the sinuses, may be comparable to plain sinus radiography in diagnosing acute sinusitis.10 In one case series of patients with suspected chronic rhinosinusitis, the addition of endoscopy to symptom criteria had similar sensitivity (88.7% vs. 84.1%) but significantly improved specificity (66% vs. 12.3%) using CT as the gold standard.13

- In acute disease, CT scanning is generally reserved for persistent or recurrent symptoms to confirm sinusitis, or to investigate infectious complications (Figures 31-4 and 31-5). Radiation dose (about 10 times that of plain radiography) can be lowered with careful choice of technical factors.1