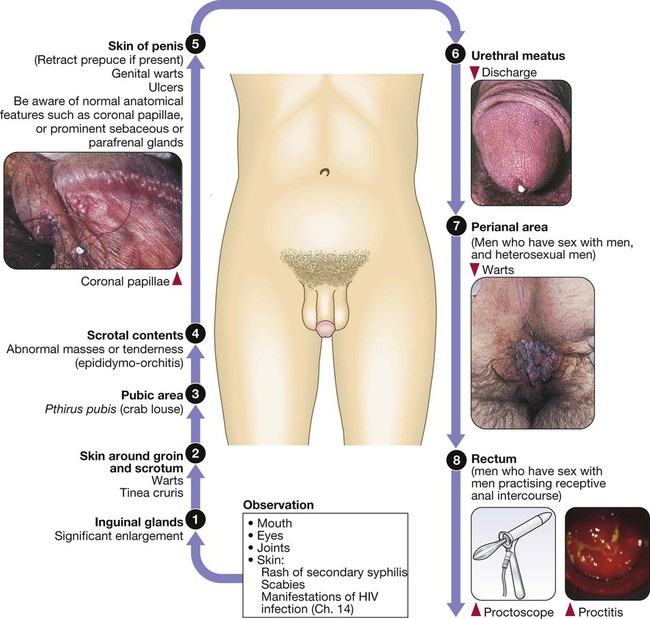

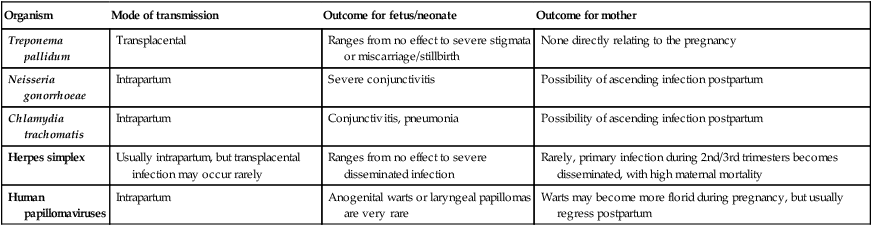

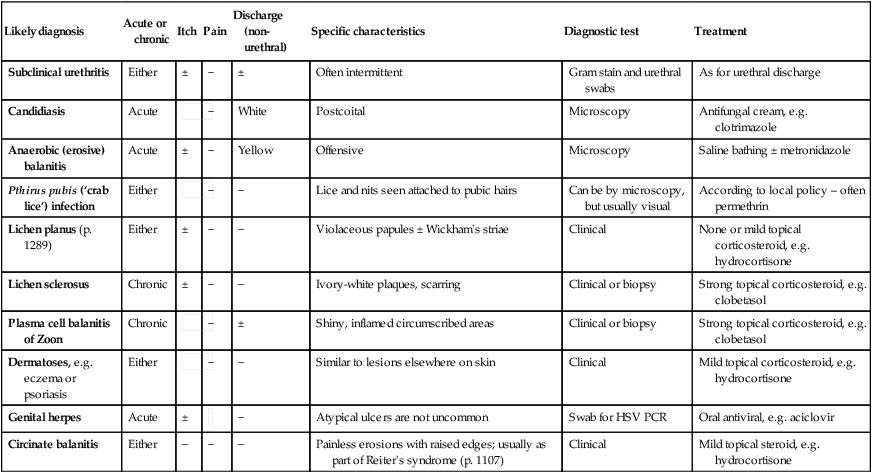

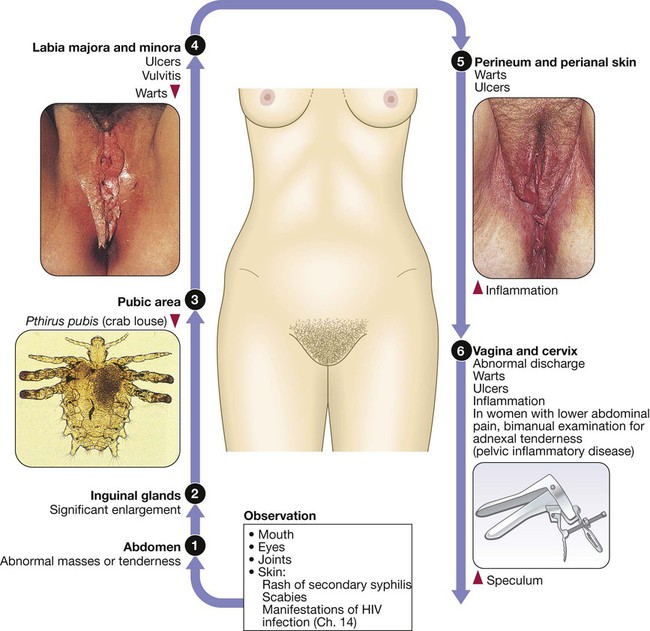

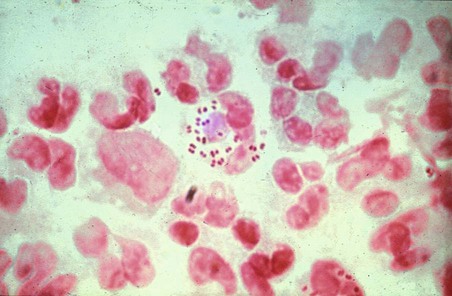

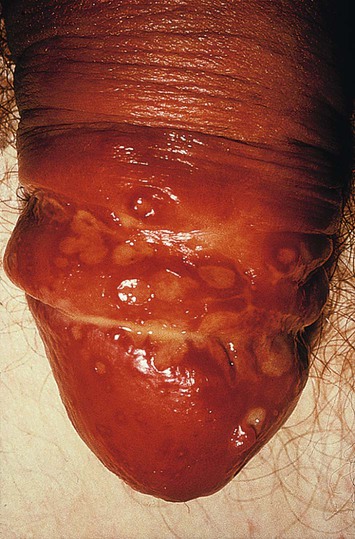

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a group of contagious conditions whose principal mode of transmission is by intimate sexual activity involving the moist mucous membranes of the penis, vulva, vagina, cervix, anus, rectum, mouth and pharynx, along with their adjacent skin surfaces. A wide range of infections may be sexually transmitted, including syphilis, gonorrhoea, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), genital herpes, genital warts, chlamydia and trichomoniasis. Bacterial vaginosis and genital candidiasis are not regarded as STIs, although they are common causes of vaginal discharge in sexually active women. Chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) and granuloma inguinale are usually seen in tropical countries. Hepatitis viruses A, B, C and D (p. 948) may be acquired sexually, as well as by other routes. The World Health Organization estimates that 448 million curable STIs (Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, gonorrhoea and syphilis) occur world-wide each year. In the UK in 2010, the most common treatable STIs diagnosed were chlamydia (more than 200 000 cases) and gonorrhoea (19 000 cases). Genital warts are the second most common complaint seen in genitourinary medicine (GUM) departments. In addition to causing morbidity themselves, STIs may increase the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV infection (Ch. 14). As coincident infection with more than one STI is seen frequently, GUM clinics routinely offer a full set of investigations at the patient’s first visit (pp. 412–413), regardless of the reason for attendance. In other settings, less comprehensive investigation may be appropriate. The extent of the examination largely reflects the likelihood of HIV infection or syphilis. Most heterosexuals in the UK are at such low risk of these infections that routine extragenital examination is unnecessary. This is not the case in parts of the world where HIV is endemic, or for men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. In other words, the extent of the examination is determined by the sexual history (Box 15.1). A detailed sexual history is imperative (see Box 15.1), as this informs the clinician of the degree of risk for certain infections, as well as specific sites that should be sampled; for example, rectal samples should be taken from men who have had unprotected anal sex with other men. Sexual partners, whether male or female, and casual or regular, should be recorded. Sexual practices – insertive or receptive vaginal, anal, orogenital or oroanal – should be noted, as should choice of contraception for women, and condom use for both sexes. The presence of an STI in a child may be indicative of sexual abuse, although vertical transmission may explain some presentations in the first 2 years. In an older child and in adolescents, STI may be the result of voluntary sexual activity. Specific issues regarding the management of STI and other infections in adolescence are discussed in Box 13.27 (p. 313). A presumptive diagnosis of urethritis can be made from a Gram-stained smear of the urethral exudate (Fig. 15.1), which will demonstrate significant numbers of polymorphonuclear leucocytes (≥ 5 per high-power field). A working diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis is made if Gram-negative intracellular diplococci (GNDC) are seen; if no GNDC are seen, a label of NSU is applied. This depends on local epidemiology and the availability of diagnostic resources. Treatment is often presumptive, with prescription of multiple antimicrobials to cover the possibility of gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia. This is likely to include a single-dose treatment for gonorrhoea, which is desirable because it eliminates the risk of non-adherence. The recommended agents for treating gonorrhoea vary according to local antimicrobial resistance patterns (p. 422). Appropriate treatment for chlamydia (p. 423) should also be prescribed because concurrent infection is present in up to 50% of men with gonorrhoea. Non-gonococcal, non-chlamydial urethritis is treated as for chlamydia. The most common cause of ulceration is genital herpes. Classically, multiple painful ulcers affect the glans, coronal sulcus or shaft of penis (Fig. 15.2), but solitary lesions occur rarely. Perianal ulcers may be seen in MSM. The diagnosis is made by gently scraping material from lesions and sending this in an appropriate transport medium for culture or detection of HSV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Increasingly, laboratories will also test for Treponema pallidum by PCR. In the UK, the possibility of syphilis or any other ulcerating STI is much less likely unless the patient is an MSM and/or has had a sexual partner from a region where tropical STIs are more common. The classic lesion of primary syphilis (chancre) is single, painless and indurated; however, multiple lesions are seen rarely and anal chancres are often painful. Diagnosis is made in GUM clinics by dark-ground microscopy and/or PCR on a swab from a chancre, but in other settings by serological tests for syphilis (p. 420). Other rare infective causes seen in the UK include varicella zoster virus (p. 316) and trauma with secondary infection. Tropical STI, such as chancroid, LGV and granuloma inguinale, are described in Box 15.12 (p. 424). Inflammatory causes include Stevens–Johnson syndrome (pp. 1264 and 1302), Behçet’s syndrome (p. 1107) and fixed drug reactions. In older patients, malignant and pre-malignant conditions, such as squamous cell carcinoma and erythroplasia of Queyrat (intra-epidermal carcinoma), should be considered. The most common cause of genital ‘lumps’ is warts (p. 425). These are classically found in areas of friction during sex, such as the parafrenal skin and prepuce of the penis. Warts may also be seen in the urethral meatus, and less commonly on the shaft or around the base of the penis. Perianal warts are surprisingly common in men who do not have anal sex. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum and skin tags. Adolescent boys may confuse normal anatomical features such as coronal papillae (p. 412), parafrenal glands or sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots) with warts. Examination may show mucopus and erythema with contact bleeding (p. 412). In addition to the diagnostic tests on page 412, a PCR test for HSV and a request for identification of the LGV substrain should be arranged if chlamydial infection is detected. Treatment is directed at the individual infections (see below). MSM may also present with gastrointestinal symptoms from infection with organisms such as Entamoeba histolytica (p. 367), Shigella spp. (p. 345), Campylobacter spp. (p. 342) and Cryptosporidium spp. (p. 369). Speculum examination often allows a relatively accurate diagnosis, with appropriate treatment to follow (Box 15.4). If the discharge is homogeneous and off-white in colour, vaginal pH is greater than 4.5, and Gram stain microscopy reveals scanty or absent lactobacilli with significant numbers of Gram-variable organisms, some of which may be coating vaginal squamous cells (so-called Clue cells, Fig. 15.3), the likely diagnosis is BV. If there is vulval and vaginal erythema, the discharge is curdy in nature, vaginal pH is less than 4.5, and Gram stain microscopy reveals fungal spores and pseudohyphae, the diagnosis is candidiasis. Trichomoniasis tends to cause a profuse yellow or green discharge and is usually associated with significant vulvovaginal inflammation. Diagnosis is made by observing motile flagellate protozoa on a wet-mount microscopy slide of vaginal material.

Sexually transmitted infections

Clinical examination in women

Approach to patients with a suspected STI

STI in children

Presenting problems in men

Urethral discharge

Investigations

Gram-negative diplococci are seen within polymorphonuclear leucocytes.

Management

Genital ulceration

Genital lumps

Proctitis in men who have sex with men

Presenting problems in women

Vaginal discharge

Sexually transmitted infections