Patient Story

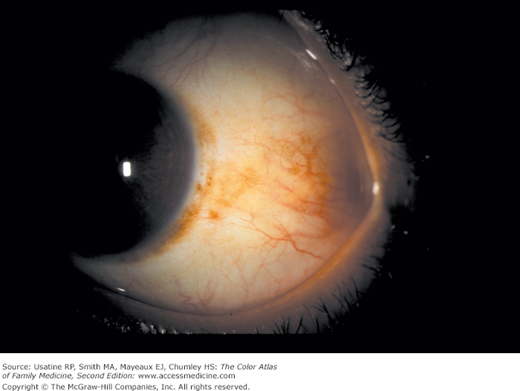

A 40-year-old white man came to see his physician about a brown spot in his eye (Figure 14-1). He noticed this spot many years ago, but after recently reading information on the Internet about brown spots in the eye, became concerned about ocular melanoma. He thinks the spot has changed in size. He denies any eye discomfort or visual changes. He was referred for a biopsy, and the pathology showed a benign nevus that did not require further treatment.

Introduction

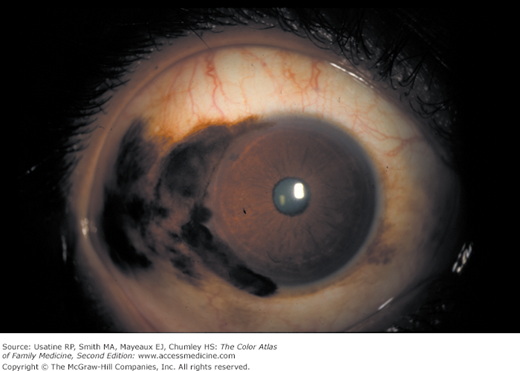

Scleral and conjunctival pigmentation is common and usually benign. Nevi can be observed and referred if they change in size. Primary acquired melanosis (PAM) must be biopsied because PAM with atypia has malignant potential, whereas PAM without atypia does not. Conjunctival melanoma is rare, but deadly.

Epidemiology

Although there is little information on the prevalence of ocular pigmentation other than physiologic (racial) melanosis, in a study of pigmented lesions referred for biopsy, investigators reported that 52% were nevi, 21% were PAM, and 25% were melanoma.1

- Scleral and conjunctival nevi (see Figures 14-1 and 14-2) are the most common cause of ocular pigmentation in light-skinned races. The pigmentation is generally noticeable by young adulthood, and is more common in whites.2

- Physiologic (racial) melanosis (Figure 14-3) is seen in 90% of black patients.3 It can be congenital, and often presents early in life.

- PAM (Figure 14-4) is generally noted in middle-aged to older adults,4,5 and is also more common in whites.

- Conjunctival melanoma (Figures 14-5, 14-6, and 14-7) is rare, occurring in 0.000007% (7 per 1,000,000) of whites; it is even less common in other races.5

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiology of scleral or conjunctival nevi is not well understood. Racial melanosis is genetically determined. Conjunctival melanoma can arise from PAM with severe atypia, nevi, or de novo.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree