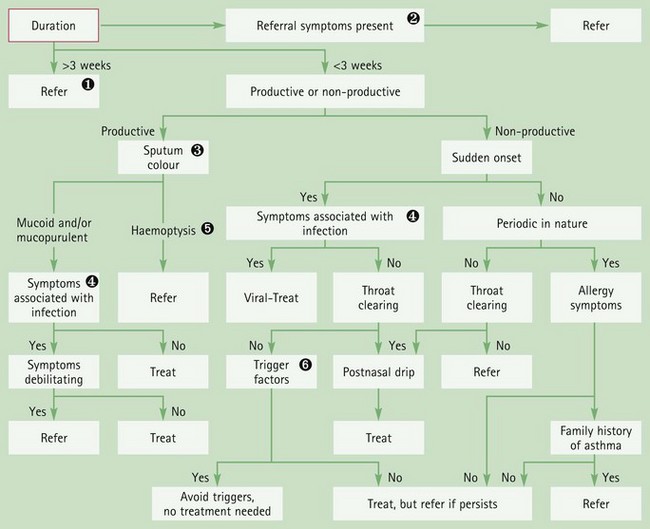

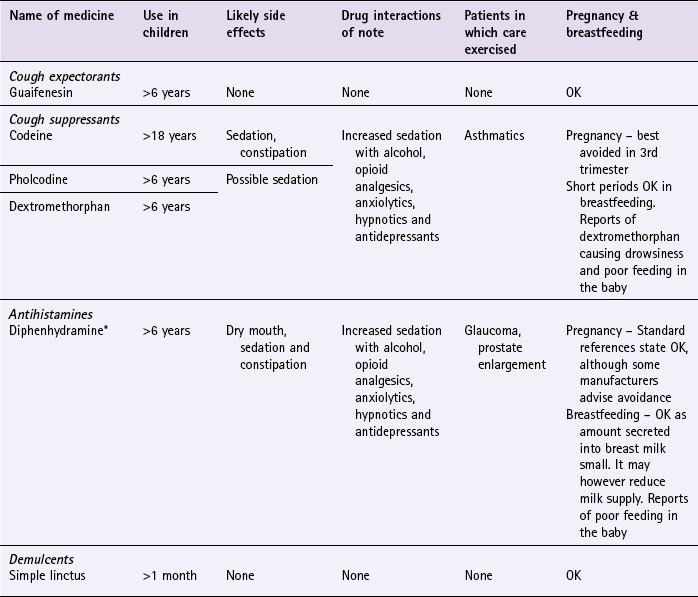

Chapter 1 Background The pharynx is divided into three sections: • nasopharynx, which exchanges air with the nasal cavity and moves particulate matter toward the mouth • oropharynx and laryngopharynx, which serve as a common passageway for air and food • laryngopharynx, which connects with the oesophagus and the larynx and, like the oropharynx, serves as a common pathway for the respiratory and digestive systems. The most likely cause of acute cough in primary care for all ages is viral URTI. Recurrent viral bronchitis is most prevalent in preschool and young school-aged children and is the most common cause of persistent cough in children of all ages. Table 1.1 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence. Table 1.1 Causes of cough and their relative incidence in community pharmacy As viral infection is the most likely cause of cough encountered by pharmacists it is logical to ask questions that help to confirm or refute this assumption. However, it is important to differentiate other causes of cough from viral causes and also refer those cases of cough that might have more serious pathology. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 1.2). Specific questions to ask the patient: Cough Upper airways cough syndrome (previously referred to as postnasal drip): Postnasal drip has recently (2006) been broadened to include a number of rhinosinus conditions related to cough. The umbrella term of upper airways cough syndrome (UACS) is being adopted. Acute bronchitis: Most cases are seen in autumn or winter and symptoms are similar to viral URTI but patients also tend to exhibit dyspnoea and wheeze. The cough usually lasts for 7–10 days but can persist for three weeks. The cause is normally viral, but sometimes bacterial. Symptoms will resolve without antibiotic treatment, regardless of the cause. Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup): Symptoms are triggered by a recent viral infection, with parainfluenza virus accounting for 75% of cases, although other viral pathogens implicated include the rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus. It affects infants aged between 3 months and 6 years old and affects 2 to 6% of children. The incidence is highest between 1 and 2 years of age and occurs in boys more than girls; it is more common in autumn and winter months. It often follows on from an URTI and occurs in the late evening and night. The cough can be severe and violent and described as having a barking (seal-like) quality. In between coughing episodes the child may be breathless and struggle to breathe properly. Typically, symptoms improve during the day and often recur again the following night, with the majority of children seeing symptoms resolve in 48 hours. Warm moist air as a treatment for croup has been used since the 19th century. This is either done by moving the child to a bathroom and running a hot bath or shower or by boiling a kettle in the room. However, UK guidelines (Prodigy, 2011) do not advocate humidification as there is no evidence to support its use. Chronic bronchitis: Chronic bronchitis (CB), along with emphysema, is characterised by the destruction of lung tissue and collectively known as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) The prevalence of COPD in the UK is uncertain. However, figures from the Health and Safety Executive (2010) estimate that over a million individuals currently have a diagnosis of COPD, and accounts for 25 000 deaths each year. Asthma: The exact prevalence of asthma is unknown due to differing terminologies and definitions plus difficulties in correct diagnosis, especially in children, and co-morbidity with COPD in the elderly. Best estimate of asthma prevalence in adults is approximately 4%, but it may be up to 10%. In children the figures are higher (10–15%) because a proportion of children will ‘grow out’ of it and be symptom free by adulthood. Pneumonia (community acquired): Bacterial infection is usually responsible for pneumonia and most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (80% of cases), although other pathogens are also responsible, e.g. Chlamydia and Mycoplasma. Initially, the cough is non-productive and painful (first 24 to 48 hours), but rapidly becomes productive, with sputum being stained red. The intensity of the redness varies depending on the causative organism. The cough tends to be worst at night. The patient will be unwell, with a high fever, malaise, headache, breathlessness, and experience pleuritic pain (inflammation of pleural membranes, manifested as pain to the sides) that worsens on inspiration. Urgent referral to the doctor is required as antibiotics should be started as soon as possible. Medicine-induced cough or wheeze: A number of medicines may cause bronchoconstriction, which presents as cough or wheeze. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are most commonly associated with cough. Incidence might be as high as 16%; it is not dose related and time to onset is variable, ranging from a few hours to more than 1 year after the start of treatment. Cough invariably ceases after withdrawal of the ACE inhibitor but takes 3 to 4 weeks to resolve. Other medicines that are associated with cough or wheeze are NSAIDs and beta-blockers. If an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is suspected then the pharmacist should discuss alternative medication with the prescriber, for example the incidence of cough with angiotension II receptor blockers is half that of ACE Inhibitors. Heart failure: Heart failure is a condition of the elderly. The prevalence of heart failure rises with increasing age; 3 to 5% of people aged over 65 are affected and this increases to approximately 10% of patients aged 80 and over. Heart failure is characterised by insidious progression and diagnosing early mild heart failure is extremely difficult because symptoms are not pronounced. Often, the first symptoms patients experience are shortness of breath, orthopnoea and dyspnoea at night. As the condition progresses from mild/moderate to severe heart failure patients might complain of a productive, frothy cough, which may have pink-tinged sputum. Bronchiectasis: Bronchiectasis is caused by irreversible dilation of the bronchi. Characteristically, the patient has a chronic cough of very long duration, which produces copious amounts of mucopurulent sputum (green-yellow in colour) that is usually foul smelling. The cough tends to be worse in the morning and evening. In long-standing cases the sputum is said to display characteristic layering with the top being frothy, the middle clear and the bottom dense with purulent particles. Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is transmitted primarily by inhalation. After many decades of decline, the number of new TB cases occurring in industrialised countries is now starting to increase. In 2009, UK figures showed that over 9000 cases were notified – an increase of 4% on the previous year and the highest number for nearly 30 years. The incidence is higher in inner city areas (especially London and the West Midlands), among the elderly and immigrants from developing countries. TB is characterised by its slow onset and initial mild symptoms. The cough is chronic in nature and sputum production can vary from mild to severe with associated haemoptysis. Other symptoms of the condition are malaise, fever, night sweats and weight loss. However, not all patients will experience all symptoms. A patient with a productive cough for more than 3 weeks and exhibiting one or more of the associated symptoms should be referred for further investigation, especially if they fall into one of the groups listed above. Chest X-rays and sputum smear tests can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Carcinoma of the lung: A number of studies have shown that between 20 and 90% of patients will develop a cough at some point during the progression of carcinoma of the lung. The possibility of carcinoma increases in long-term cigarette smokers who have had a cough for a number of months or who develop a marked change in the character of their cough. The cough produces small amounts of sputum that might be blood streaked. Other symptoms that can be associated with the cough are dyspnoea, weight loss and fatigue. Lung abscess: A typical presentation is of a non-productive cough with pleuritic pain and dyspnoea. It is more common in the elderly. Signs of infection such as malaise and fever can also be present. Later the cough produces large amounts of purulent and often foul-smelling sputum. Spontaneous pneumothorax (collapsed lung): Rupture of the bullae (the small air or fluid filled sacs in the lung) can cause spontaneous pneumothorax but normally there is no underlying cause. It affects approximately 1 in 10 000 people, usually tall, thin men between 20 and 40 years old. Cigarette smoking and a family history of pneumothorax are contributing risk factors. This can be a life-threatening disorder causing a non-productive cough and severe respiratory distress. The patient experiences sudden sharp unilateral chest pain that worsens on inspiration. The symptoms often begin suddenly, and can occur during rest or sleep. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) does not usually present with cough but patients with this condition might cough when recumbent (lying down). The patient might show symptoms of reflux or heartburn. Patients with GORD have increased cough reflex sensitivity and respond well to proton pump inhibitors. It should always be considered in all cases of unexplained cough. Nocardiasis: Nocardiasis is an extremely rare bacterial infection caused by Nocardia asteroides; it is transmitted primarily by inhalation. It is very unlikely a pharmacist will ever encounter this condition and is included in this text for the sake of completeness. It has a higher incidence in the elderly population, especially men. The sputum is purulent, thick and possibly blood tinged. Fever is prominent and night sweats, pleurisy, weight loss and fatigue might also be present. Figure 1.1 will aid the differentiation between serious and non-serious conditions of cough in adults. A number of active ingredients have been formulated to help expectoration, including guaifenesin, ammonium salts, ipecacuanha, creosote and squill. The majority of products marketed in the UK for productive cough contain guaifenesin, although products containing squill (e.g. Buttercup Syrup) are available. The clinical evidence available for any active ingredient is limited. Older ingredients such as ammonium salts, ipecacuanha and squill were traditionally used to induce vomiting as it was believed that at subemetic doses they would cause gastric irritation, triggering reflex expectoration. This has never been proven and belongs in the annals of folklore. Guaifenesin is thought to stimulate secretion of respiratory tract fluid, increasing sputum volume and decreasing viscosity so assisting in removal of sputum. Guaifenesin is the only active ingredient that has any evidence of effectiveness. Two studies identified by Smith, Schroeder & Fahey (Cochrane Review 2008) found conflicting results for guaifenesin as an expectorant. In the largest study (n = 239) participants stated guaifenesin significantly reduced cough frequency and intensity compared to placebo. In the smaller trial (n = 65) guaifenesin was stated to have an antitussive not expectorant effect. Codeine is generally accepted as a standard or benchmark antitussive against which all others are judged. A review by Eddy et al (1970) showed codeine to be an effective antitussive in animal models, and cough-induced studies in humans have also shown codeine to be effective. However, these findings appear to be less reproducible in acute and pathological chronic cough. More recent studies have failed to demonstrate a significant clinical effect of codeine compared with placebo in patients suffering with acute cough. Greater voluntary control of the cough reflex by patients has been suggested for the apparent lack of effect codeine has on acute cough. Pholcodine, like codeine, has been subject to limited clinical trials, with the majority being either animal models or citric-acid-induced cough studies in man. These studies have shown pholcodine to have antitussive activity. A review by Findlay (1988) concluded that, on balance, pholcodine appears to possess antitussive activity but advocates the need for better, well-controlled studies. Citric-acid-induced cough studies have demonstrated significant antitussive activity compared to placebo and results from chronic cough trials support an antitussive activity for diphenhydramine. However, trials that showed a significant reduction in cough frequency suffered from having small patient numbers, thus limiting their usefulness. Additionally, poor methodological design of trials investigating the antitussive activity of diphenhydramine in acute cough makes assessment of its effectiveness difficult. A recent review concluded ‘Presumptions about efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans are not unequivocally substantiated in literature’ (Bjornsdottir et al 2007). Less-sedating antihistamines, have also not been shown to have any benefit in treating coughs compared to placebo (Smith et al 2008). In 2008 a Cochrane review examining the treatment of acute cough in both adults and children concluded there was no good evidence to support the effectiveness of cough medicines in acute cough (Smith et al 2008). In addition, there has been growing evidence of the potential harm that these agents can pose to young children, either due to adverse effects, or from accidental inappropriate dosing (Isbister et al 2010; Vassilev et al 2010). Based on the lack of efficacy and potential harm, the MHRA/CHM (in 2008 and 2009 respectively) recommended that cough and cold mixtures should not be used in children under 6 years of age, and should only be used in children aged 6 to 12 on the advice of a pharmacist or doctor and treatment limited to 5 days or less. Prescribing information relating to the cough medicines reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 1.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with cough are given in Hints and Tips Box 1.1. Bjornsdottir, I, Einarson, TR, Guomundsson, LS, et al. Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(6):577–583. Eddy, NB, Friebel, H, Hahn, KJ, et al. Codeine and its alternatives for pain and cough relief. Geneva: World Health Organ; 1970. [1–253]. Findlay, JWA. Review Articles: Pholcodine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1988;13:5–17. Isbister, GK, Prior, F, Kilham, HA. Restricting cough and cold medicines in children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2012;48:91–98. Smith, SM, Schroeder, K, Fahey, T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001831. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub3]. Vassilev, ZP, Kabadi, S, Villa, R. Safety and efficacy of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines for use in children. Expert Opinion Drug Safety. 2010;9(2):233–242. Dicpinigaitis, PV, Colice, GL, Goolsby, MJ, et al. Acute cough: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cough. 2009;5:11. Knutson, D, Aring, A. Viral croup. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:535–540. 541–2 MeReC Bulletin. The management of common infections in primary care Volume 17 Number 3 December 2006. Morice, AH, McGarvey, L, Pavord, I. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006;61:S1–24. NICE Guidance on TB. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG117, 2011. Available at (accessed 1 November 2012) Pratter, MR. Overview of common causes of chronic cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):59S–62S. Russell, KF, Liang, Y, O’Gorman, K, et al. Glucocorticoids for croup. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001955. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub3 Sahn, S, Heffner, J. Spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:868–874. SIGN and BTS, British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline (revised 2011). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and The British Thoracic Society 2011. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/101/index.html. (accessed 1 November 2012) The common cold It is extremely likely that someone presenting with cold symptoms will have a viral infection. Table 1.4 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence. Table 1.4 Causes of cold and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Most people will accurately self-diagnose a common cold and it is the pharmacist’s role to confirm this self-diagnosis and assess the severity of the symptoms as some patients, for example the elderly, infirm and those with existing medical conditions might need greater support and care. In the first instance, the pharmacist should make an overall assessment of the person’s general state of health. Anyone with debilitating symptoms that effectively prevents them from doing their normal day-to-day routine should be managed more carefully. Whilst it is likely that a patient will have a common cold, severe colds can mimic the symptoms of flu, which is the only condition of any real significance that has to be eliminated before treatment can be given, although secondary complications can occur. Asking symptom specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 1.5). Specific questions to ask the patient: The common cold

Respiratory system

General overview of the anatomy of the respiratory tract

Upper respiratory tract

Pharynx

Cough

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most Likely

Viral infection

Likely

Upper airways cough syndrome (formerly known as postnasal drip and includes allergies), acute bronchitis

Unlikely

Croup, chronic bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, ACE inhibitor induced

Very unlikely

Heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, pneumothorax, lung abscess, nocardiasis, GORD

![]() Table 1.2

Table 1.2

Question

Relevance

Sputum colour

Mucoid (clear and white) is normally of little consequence and suggests that no infection is present

Yellow, green or brown sputum normally indicates infection. Mucopurulent sputum is generally caused by a viral infection and does not require automatic referral

Haemoptysis can either be rust coloured (pneumonia), pink tinged (left ventricular failure) or dark red (carcinoma). Occasionally, patients can produce sputum with bright red blood as one-off events. This is due to the force of coughing causing a blood vessel to rupture. This is non-serious and does not require automatic referral

Nature of sputum

Thin and frothy suggests left ventricular failure

Thick, mucoid to yellow can suggest asthma

Offensive foul-smelling sputum suggests either bronchiectasis or lung abscess

Onset of cough

A cough that is worse in the morning may suggest upper airways cough syndrome, bronchiectasis or chronic bronchitis

Duration of cough

URTI cough can linger for more than 3 weeks and is termed ‘postviral cough’. However, coughs lasting longer than 3 weeks should be viewed with caution as the longer the cough is present the more likely serious pathology is responsible; for example, the most likely diagnoses of cough are as follows:

at 3 days duration will be a URTI;

at 3 weeks duration will be acute or chronic bronchitis;

and at 3 months duration conditions such as chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis and carcinoma become more likely

Periodicity

Adult patients with recurrent cough might have chronic bronchitis, especially if they smoke

Care should be exercised in children who present with recurrent cough and have a family history of eczema, asthma or hay fever. This might suggest asthma and referral would be required for further investigation

Age of the patient

Children will most likely be suffering from a URTI but asthma and croup should be considered

With increasing age conditions such as bronchitis, pneumonia and carcinoma become more prevalent

Smoking history

Patients who smoke are more prone to chronic and recurrent cough. Over time this might develop in to chronic bronchitis and COPD

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

Expectorants

Cough suppressants (antitussives)

Codeine

Pholcodine

Antihistamines

Cough medication for children

Practical prescribing and product selection

References

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Viral infection

Likely

Rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, otitis media

Unlikely

Influenza

![]() Table 1.5

Table 1.5

Question

Relevance

Onset of symptoms

Peak incidence of flu is in the winter months; the common cold occurs any time throughout the year

Flu symptoms tend to have a more abrupt onset than the common cold – a matter of hours rather than 1 or 2 days

Summer colds are common but they must be differentiated from seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever)

Nature of symptoms

Marked myalgia, chills and malaise are more prominent in flu than the common cold. Loss of appetite is also common with flu

Aggravating factors

Headache/pain that is worsened by sneezing, coughing and bending over suggests sinus complications

If ear pain is present, especially in children, middle ear involvement is likely![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Respiratory system