Renal Arteries

Renal ArteriesSurgical Anatomy of the Renal Arteries

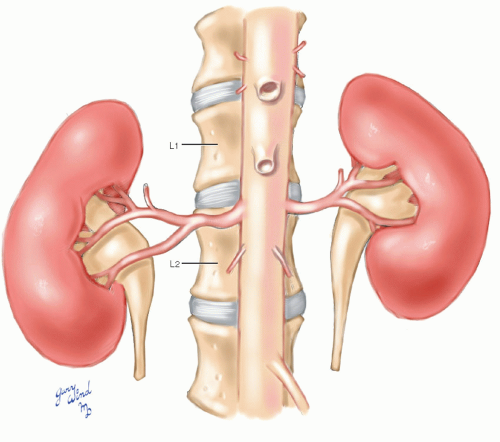

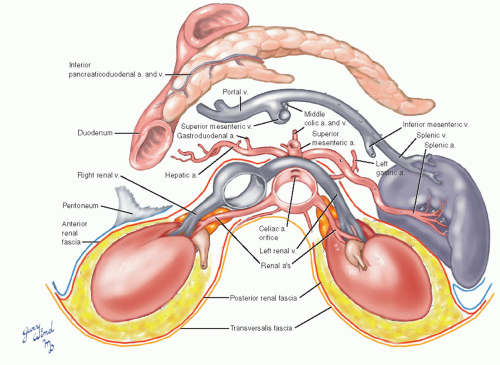

The renal arteries arise from the abdominal aorta at approximately the level of the disc between the first two lumbar vertebrae (Fig. 11-1). The left is usually slightly more cephalad than the right, and supernumerary vessels are not uncommon. Because the aorta is elevated on the promontory of the spinal

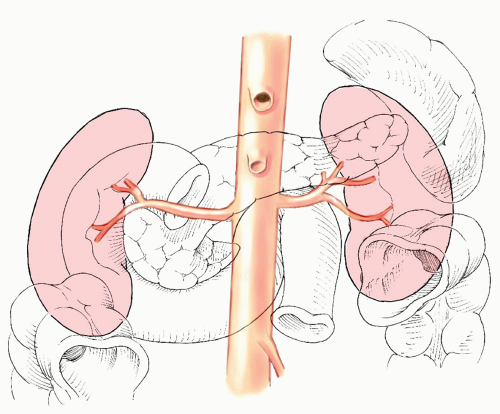

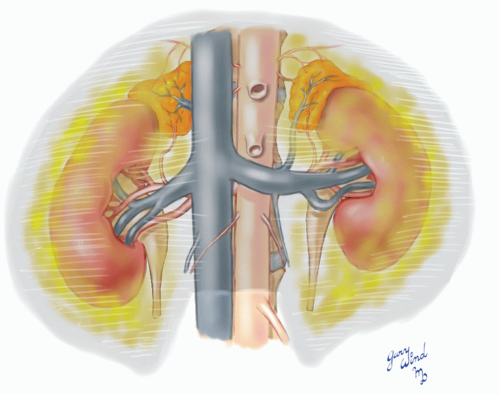

column and the kidneys rest in the adjacent gutters, the angle formed by the renal vessels with the aorta is almost 90° (Fig. 11-2). The position of the aorta to the left of midline makes the right renal artery longer than the left.

column and the kidneys rest in the adjacent gutters, the angle formed by the renal vessels with the aorta is almost 90° (Fig. 11-2). The position of the aorta to the left of midline makes the right renal artery longer than the left.

Fig. 11-2 The renal arteries drape posteriorly over the spinal column. The right renal artery often divides behind the inferior vena cava. |

Fasciae

The kidneys are embedded in a layer of fat and enclosed by fascial layers in front and back. These anterior and posterior renal fasciae fuse laterally with

each other and with the posterior parietal peritoneum. The anterior and posterior renal fasciae continue loosely across the midline ventral and dorsal to the great vessels, respectively. The posterior layer lies on the transversalis fascia.

each other and with the posterior parietal peritoneum. The anterior and posterior renal fasciae continue loosely across the midline ventral and dorsal to the great vessels, respectively. The posterior layer lies on the transversalis fascia.

Fig. 11-3 The kidneys and perinephric fat are enclosed by an envelope of renal fascia that tapers around the adrenals above and the ureters below. |

The layers of the renal fascia taper above to enclose the adrenal glands on each side and taper below to ensheath the proximal ureters (Fig. 11-3). The anterior renal fascia is partly covered by the posterior parietal peritoneum. The remaining part of

the fascia over the right kidney is covered by the second portion of the duodenum and the hepatic flexure of the colon (Fig. 11-4). On the left, the part of the anterior renal fascia not in contact with the peritoneum is covered by the tail of the pancreas, the spleen, and the splenic flexure of the colon.

the fascia over the right kidney is covered by the second portion of the duodenum and the hepatic flexure of the colon (Fig. 11-4). On the left, the part of the anterior renal fascia not in contact with the peritoneum is covered by the tail of the pancreas, the spleen, and the splenic flexure of the colon.

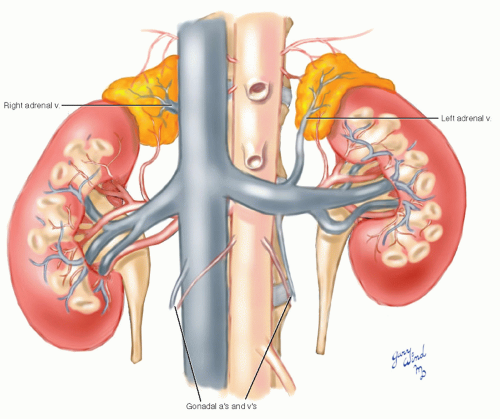

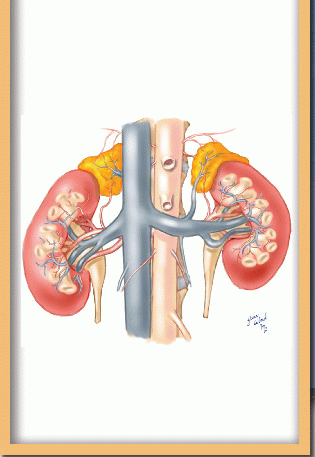

Vessels

The renal arteries lie posterior to the corresponding renal veins on each side, and the right renal artery passes behind the inferior vena cava where the first branch points are commonly found (Fig. 11-5). The left renal artery is most commonly found near the cephalad border of the long left renal vein. Each renal artery usually sends a small branch to the ipsilateral adrenal gland, complementing the aortic and inferior phrenic artery branches to those organs. Near the hilum of each kidney, the renal artery divides into four or five branches that enter the kidney between the vein branches anteriorly and the calyces posteriorly.

The left renal vein serves as a landmark for locating the level of the renal artery origins. The left renal artery is usually found beneath the left renal vein near the cephalad margin of the vein. The right renal vein and artery junctions with the inferior vena cava and aorta are slightly caudal to the left. Both renal veins may receive a lumbar vein. In addition, the left renal vein receives the left adrenal and left gonadal veins.

Exposure of the Renal Arteries

Surgical exposure of the renal arteries may be necessary to treat traumatic injuries, aneurysms, or chronic stenoses. A common indication for isolation of the renal artery in the traumatized patient is to obtain vascular control before exploring a parenchymal injury. Vascular repair of a renal artery injury is indicated only for pseudoaneurysms or dissection with preserved flow. Because most injuries result in thrombosis and irreversible ischemia, reported outcomes for vascular repair are similar to nephrectomy.1,2 The indications for repair of renal artery aneurysms are detailed elsewhere.3,4 These lesions are often located in the distal arterial branches or the renal hilum; therefore, advanced techniques such as extracorporeal repair should be available when surgery is indicated.5 Chronic renal artery stenoses may be due to fibromuscular dysplasia (10%) or atherosclerosis (90%). Percutaneous balloon angioplasty without a stent is considered the treatment of choice for renovascular hypertension due to fibromuscular dysplasia.6 Regardless of the type of intervention, long-term cure rates are lower for atherosclerotic lesions. The clinical evidence summarizing the effectiveness of angioplasty versus medical therapy for treating atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis is published elsewhere.7 Many surgeons favor open renal artery revascularization over angioplasty and stenting, especially after failed percutaneous therapy.8,9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree