95

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ ACTIVE PHYSICAL THERAPY (PT)

■ PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS AS PART OF A PAIN REHABILITATION PLAN

■ MODALITIES USED IN ACUTE AND CHRONIC PAIN CONDITIONS

Rehabilitation may be described as a “return to ability … the return to the fullest physical, mental, social, vocational, and economic usefulness that is possible for the individual.” The focus is placed more on one’s abilities rather than his or her disabilities (1). The patient with substance abuse or addictive disorder may also be faced with an additional challenge of comorbid chronic pain. A recent systematic review found that nonmedical users of prescription opioids had two to three times greater mental health problems and pain than did the general population (2). Incorporating a rehabilitation-based approach to treating chronic pain can serve as a valuable tool for managing chronic pain patients with and without addictive disease (3,4).

A number of chronic and acute pain conditions can benefit from a wide range of nonpharmacologic interventions. A rehabilitation-based approach focuses on a staged approach to addressing the range of acute to chronic pain conditions. A focused history and physical exam can help to identify areas of impairment and guide subsequent treatment interventions and the development of a comprehensive rehabilitation plan. More chronic presentations may need psychological and vocational interventions as well. In carefully selected patients, some interventional procedures (i.e., epidural injections for acute radicular pain or trigger point injections for myofascial pain complaints) may provide additional tools for the pain clinician but will not be the focus of this chapter. The chapter overviews active and passive therapies for acute and chronic pain conditions, including modalities, active physical and occupational therapy, and team approaches to comprehensive care.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has embraced the concept of a “biopsychosocial model” for assessing and treating chronic pain patients, including those with substance abuse or other psychiatric disorders (5). A rehabilitation approach for assessing and treating pain is based on a conceptualization of the experience of pain as only one part of the dynamic interplay between physical changes in the nervous system and psychological factors. Nociceptive pathways can be affected by tissue-related changes as well as psychosocial factors including stress, anxiety, depression, external factors such as the environment, and past experiences. The resulting pain experienced by the patient will be manifested by overt pain behaviors and suffering (6). From a rehabilitation perspective, all of these biopsychosocial factors should be considered when developing and delivering a pain management treatment program.

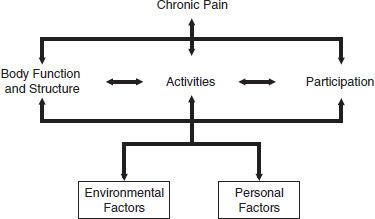

In assessing complaints, one should focus on the patient’s individual “impairments” (i.e., physical or psychological abnormality), his or her effect on function or “disability” (i.e., a restriction or lack of ability to perform a function), and how that affects his or her place in society or creates a “handicap” (7). The WHO has broadened the concept of “chronic pain” to include the unique relationship among an individual patient’s pain and related activities, function, and participation in society, including the influence of related environmental and personal factors (8) (see Fig. 95-1).

FIGURE 95-1 The WHO model of factors interacting with chronic pain and activity.

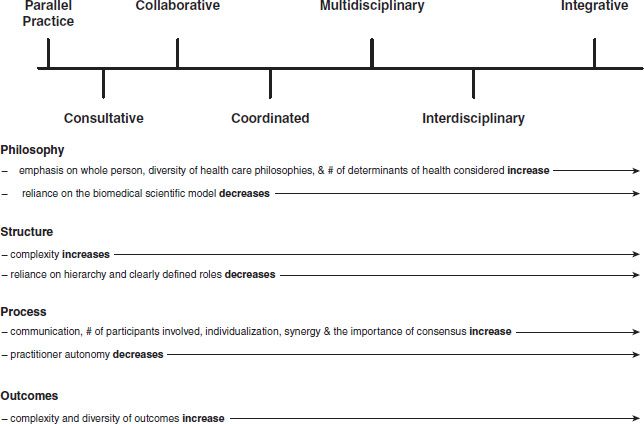

A conceptual model based on disease management approaches similar to those for diabetes, heart disease, and asthma can be applied to the treatment of many chronic pain conditions (9) (see Fig. 95-2). In this model, moving from left (parallel practice) to right (integrative) includes moving from a biomedical, disease-focused approach to a collaborative integrative team-based treatment model. Moving across the continuum, the philosophy emphasizes the whole person, with little reliance on hierarchy and flexible roles among clinicians. Acute pain conditions typically respond to a biomedical approach focused on acute management, decreasing local soft tissue swelling, and immobilization. Similarly, parallel practice, for example, could involve an emergency team working efficiently on a patient presenting with cardiac pain. Individual roles are specifically defined, and extensive communication is not necessary. Collaborative models may involve a physician referring a patient to a different specialist for consultation. Coordinated models may include the additional use of a case manager to help coordinate delivery and communication of care. A “multidisciplinary” approach includes the use of one or a number of allied health disciplines, such as physical therapy (PT) or occupational therapy (OT) directed by a senior provider. In a multidisciplinary care, clinicians need not be in the same facility, and communication may vary, as may the transfer of records and reports. As the presenting complaint becomes more chronic, a more collaborative approach involving the coordination of multiple caregivers defines an “interdisciplinary approach” (10).

FIGURE 95-2 Models of medical care. From Boon H, et al. From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework. BMC Health Serv Res 2004;4:15.

In an interdisciplinary model, care is usually provided at one facility, where patients participate in a number of therapies, working with multiple disciplines and health care providers. Treatments may include physical and occupational therapy, psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive–behavioral therapy) and relaxation training, aerobic conditioning, education, vocational rehabilitation, and medical management. These programs can vary from 1 to 2 days per week to more comprehensive, 6 to 8 hours per day, 4 to 5 day per week, 15- to 20-day programs. Such programs are usually provided in an outpatient setting (11).

Treatments focus on helping the patient to acquire pain management skills, decrease pain, improve psychosocial functioning, and return to leisure and vocational function. We will describe allied health disciplines that can be used in a unimodal manner or as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation-based treatment plan.

ACTIVE PHYSICAL THERAPY (PT)

Physical therapy includes, among other functions, the application of modalities, physical agents (see modalities below), therapeutic exercise, functional training in home and work activities, and manual therapy (http://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/BOD/Practice/ScopeofPractice.pdf Amer Phys Therapy Association).

Physical therapy treatment primarily includes 1-hour sessions, which can include patient education, instruction in exercises and stretches, core strengthening, gait training, manual therapy, and pool or aquatic therapy, with progression of activities over several therapy visits. Patients are given short- and long-term therapy goals and instruction in exercises and stretches. The PT may also dispense equipment, braces, and supports.

The addiction clinician can refer patients for evaluation and treatment to a physical therapist. Follow-up should include monitoring for compliance. Many times, reviewing a patient’s exercise program and stretches will help to reinforce with the patient the importance of the patient’s active role in the rehabilitation process.

The goal of any referral to a physical therapist is to establish a patient in an independent therapeutic exercise program. The basic principles of a therapeutic exercise prescription include the following:

1. Functional evaluation and assessment of dysfunction and impairments

2. Evaluation and management of motor control (i.e., strength and balance)

3. Identification and management of bony and joint kinematic limitations (i.e., joint contracture, soft tissue restrictions)

4. Assessments of movement patterns followed by strategies for improvement or facilitation of synergistic movement patterns (12)

Physical Therapy Approaches to Stretching

The physical therapist can assess joint range of motion, soft tissue changes, and strength deficits as they relate to a functional unit, such as the shoulder, knee, and cervical or lumbar spine. Joint hypomobility is a frequent cause of pain and many times can be the result of poor posture, weak and inhibited muscles, and tight soft tissue. Muscle surrounding the affected area may also develop compensatory activation patterns and neural dysfunction. Various stretching techniques can be used and guided by the therapist and over time performed individually by the patient. Basic types of stretching include ballistic, passive, static, and neuromuscular facilitation. Ballistic stretching uses repetitive rapid application of force in a jerking or bouncing manner in which momentum helps to carry the body part through a range of motion until muscles are stretched to their physiologic maximums. More commonly used stretching for chronic pain includes static stretching and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF).

Static stretching techniques involve stretching an antagonist muscle passively by putting the segment in a maximal position of stretch and holding for 10 to 60 seconds. This stretching is repeated four to six times and often incorporates the patient’s own body weight, the assistance of a therapist, or stretching equipment (13). PNF techniques can be also useful for improving flexibility. Different types of PNF exercises include contract–relax, useful when range of motion is limited by muscle or soft tissue tightness, and hold–relax, which includes additional light pressure from the therapist, producing maximal stretch of the involved antagonist muscle groups. Myofascial release is a physical or occupational therapy technique that requires specific training and can accomplish stretching of deeper fascia and connective tissue. In some states, therapists may also be licensed in such interventional approaches for myofascial pain as dry needle insertion and trigger point injections (14,15).

A growing area of therapy includes stretching the peri-neural tissues or “neurodynamic therapy,” commonly used in cervical and lumbar radicular pain or peripheral nerve compression disorders (e.g., ulnar neuropathy of the elbow, median neuropathy at the wrist) (16). Here, neural tissue may become constrained in tight muscle or soft tissue causing increased nerve excitability and such symptoms as paresthesias and dysesthesias in the distribution of specific nerves. Butler and others have eloquently described stretching techniques that can be taught to a patient as part of a therapy program (17).

Aquatic Therapy

Numerous studies have found aquatic therapy to be beneficial in a variety of acute and chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia, spinal cord injury, osteoarthritis, and various orthopedic injuries (18). Therapy is usually supervised by a physical therapist, occupational therapist, or trainer. Treatment is usually in a group setting with the goal of instructing patients in the performance of exercises that can be performed in the water and continued independently. The beneficial effects of aquatic therapy include decreases in joint compression forces, the counteraction of gravitational obstacles by buoyancy, decreased pain, and reduced protective muscle spasm (19).

The physical properties of water that are useful include “weightlessness” and resistive forces against which patients can apply force.

Common indications for therapy include peripheral edema, decreased range of motion and strength, impaired balance, weight-bearing restrictions due to injury or surgery, gait abnormalities, and cardiovascular deconditioning (20,21). In chronic neck and low back pain, aquatic therapy may be provided initially, until improved conditioning permits successful application of land-based therapy. Aquatic therapy may help to eliminate fear-related avoidance of movement, to improve range of motion, and to initiate stretching and strengthening.

A significant percentage of chronic pain conditions involves disorders of the neck and lumbar spine, which accounts for a large proportion of those in need of treatment. Besides passive modalities used for acute pain management (see below), physical therapy–directed exercises may help patients improve function and decrease pain. Acute and chronic low back pain patients may benefit from referral to a physical therapist for instruction in one of a number of programs, such as lumbar stabilization or core strengthening, or for specialized directional preference treatments such as McKenzie-based therapy.

Lumbar and Cervical Stabilization

Stabilization exercises focus on strengthening weak and inhibited muscles and strengthening or “stabilizing” muscles that surround the spine, thereby improving muscular support (22). Assessing and improving the “core” is the cornerstone of any stabilization program for the lumbar spine, and similar principles can be applied to cervical and joint-related pain conditions (23). The core is defined as the lumbopelvic– hip complex, thought to include over 29 muscles attaching in this region of the body. Key lumbopelvic–hip muscles include those attaching to the lumbar spine (transversospinalis group, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and latissimus dorsi), abdominal muscles (rectus abdominus, external and internal obliques, and transversus abdominus), and key hip muscles (gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and psoas) (24). Cervical stabilization focuses on improving spine mechanics (i.e., cervical flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation), improving maladaptive postures, increasing cervical extensor and posterior scapular muscle strength, and usually stretching restricted anterior pectoralis and shoulder muscles.

The goals of core training include improving dynamic postural control, establishing optimal muscular balance and joint movement around the complex, maximizing functional strength and endurance, and increasing postural control (25). Core stabilization also provides proximal stability in the spine for more efficient movement in the lower extremities.

Common muscle impairment patterns seen with many acute and chronic low back pain patients include weak buttock muscles (i.e., gluteus medius), weak abdominals (rectus and transverse abdominus), overactive synergist muscles such as piriformis and hamstring, and shortened antagonist muscles (thigh adductors and iliopsoas) (26). In the cervical spine, many neck pain patients present with weak trapezius and scapular muscles, overactive levator scapulae, and shortened antagonists, such as the pectoralis. They often show maladaptive postures and positions of the cervical spine. All of these impairments may contribute to pain and disability and may be specific areas of assessment and treatment by the properly trained therapist. A therapy program could include strengthening exercises on an exercise ball or without specific equipment.

Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (McKenzie Therapy)

Mechanical diagnosis and therapy, commonly referred to as McKenzie therapy, is a common, specialized approach in which specially trained therapists instruct patients through a number of active positions of motion in the lumbar spine and determine whether patients are able to decrease or change the pain referral pattern from the extremities to more “centralized” low back or neck pain. This is based on the theory that an intact nucleus pulposus (cervical or lumbar), responsible for generating referred pain to a limb, will produce different symptoms in certain positions with repeated standardized end range test movements (e.g., lumbar extension [seated or standing], lumbar flexion, side bending). The most common movement is lumbar extension, although a small percentage of patients may “centralize” their symptoms with repeated flexion or trunk side bending. Those patients who respond to repeated positioning (such as lumbar extension, flexion, or side bending) are given those same exercises to do on a daily basis to help decrease symptoms (27,28).

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY (OT)

OT consists of assessment and training of patients in areas related to functional activities. Areas addressed may include specific activities of daily living (ADLs), posture, ergonomics, and body mechanics. Work site analyses may be conducted. Patients may be fitted for braces and splints. In the United States, occupational therapy may be provided in postoperative orthopedic care, such as after carpal tunnel release or upper limb fracture. An occupational therapist assesses range of motion, strength, and strength with an emphasis on improving functional, vocational, avocational (leisure), or sports-specific activities.

Posture and Body Mechanics

Many chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions of the cervical and lumbar spine, large joints (shoulder, hip), small joints (hand, wrist, ankle), and soft tissue structures (i.e., tendon, muscle, and ligaments) may be aggravated by poor posture. Basic assessment of sitting and standing posture and retraining may be a focus of individual OT sessions and can be applied at home and work. Proper standing and sitting posture will help reduce stress and strain over bony and soft tissue structures.

Body mechanics assessment and retraining can be an important clinical focus of OT in many chronic pain conditions. Proper lifting and reaching mechanics, similar to posture training, can help to improve function, decrease pain, increase tolerance for an activity, and limit injury. Simple instructions to patients to improve posture and decrease pain are included below:

Standing:

Feet shoulder width apart, shoulders even over hips

Even weight distributed over both feet

Knees straight and unlocked

Pelvis level Stomach muscles slightly engaged

Ears lined up over shoulders

Sitting:

Pelvis level, and weight is even over ischial tuberosities

Hips and knees at 90 degrees or greater

Knees and feet shoulder/hip width apart

Feet flat on floor or stable surface

Knees over ankles

Stomach muscles slightly engaged

Shoulders evenly aligned over hips (29)

Ergonomics is the science of designing equipment with the aim of increasing productivity and reducing fatigue and discomfort. This is an additional area in which OT can be of value to a patient with chronic pain. With the increased use of computers, keypads, handheld devices, and prolonged sedentary work, mostly on a computer, there has been an increase in chronic neck, shoulder, upper limb musculo-skeletal conditions, as well as low back pain. An ergonomic evaluation helps the OT to optimize positioning of equipment, keyboards, and other work site tools to help improve function and tolerance, decrease pain, and prevent injury. Physical rehabilitation programs that include ergonomic interventions for upper limb and neck pain have been found to be effective in decreasing pain and improving function in a number of studies (30,31). See figure on proper sitting/ computer setup.

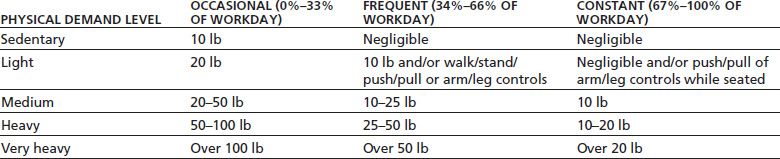

Occupational Work Rehabilitation

OT can assist in addressing patient-specific work goals. Occupational therapists can review job descriptions, perform job site analyses, and thereby help to determine whether job site or specific job modifications are needed to enable a worker or patient to perform a job safely. Occupational therapists can perform functional baseline testing to clarify an individual’s specific physical abilities and tolerances or can provide more structured and extensive testing via a functional capacity evaluation (FCE) (32). FCEs are done by specially trained physical or occupational therapists and usually take place over a 3- to 4-hour period. They help determine physical tolerances for lifting, pulling, and pushing capabilities and are typically integrated with validity testing (33). The FCE can help to determine whether a patient can meet specific job demands as defined by the U.S. Department of Labor (34). Work or physical demand levels include sedentary, light, medium, and heavy and clarify both the amount of time an activity is done (i.e., infrequent, occasional, frequent, and constant) as a percentage of the work day as well as the frequency of repetitions (see Table 95-1).

TABLE 95-1 DICTIONARY OF OCCUPATIONAL TITLES SYSTEM FOR CLASSIFYING THE STRENGTH DEMANDS OF WORK

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree