Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

Demonstrate an understanding of the formulary system and its application in a purchasing and inventory system.

Demonstrate an understanding of the formulary system and its application in a purchasing and inventory system.

Execute lending and borrowing pharmaceutical transactions between pharmacies.

Execute lending and borrowing pharmaceutical transactions between pharmacies.

Apply the proper principles and processes when receiving and storing pharmaceuticals.

Apply the proper principles and processes when receiving and storing pharmaceuticals.

Identify key techniques for reviewing packaging, labeling, and storage considerations when handling pharmaceutical products.

Identify key techniques for reviewing packaging, labeling, and storage considerations when handling pharmaceutical products.

Demonstrate an understanding of pharmaceutical products that require special handling within the purchasing and inventory system.

Demonstrate an understanding of pharmaceutical products that require special handling within the purchasing and inventory system.

Demonstrate both an understanding and the application of appropriate processes for maintaining and managing a pharmaceutical inventory.

Demonstrate both an understanding and the application of appropriate processes for maintaining and managing a pharmaceutical inventory.

Complete the appropriate processes in the handling of pharmaceutical recalls and the disposal of pharmaceutical products.

Complete the appropriate processes in the handling of pharmaceutical recalls and the disposal of pharmaceutical products.

Key Terms

| bar code medication administration (BCMA) | A process in which the nurse scans a bar code on a patient’s ID band and the bar code specific to the medication prior to medication administration. Documentation of the administration is automatically entered into the patient’s electronic health record. |

| direct purchasing | Buying directly from a manufacturer. It typically involves the execution of a purchase order from the pharmacy to the manufacturer of the drug. |

| group purchasing organization (GPO) | An organized group that contracts with manufacturers to purchase pharmaceuticals at discounted prices, in return for a guaranteed minimum purchase volume. Hospitals, independent community pharmacies, and other retail chain pharmacies become members of a GPO to leverage buying power and take advantage of the lower prices that manufacturers offer to the GPOs. |

| just-in-time inventory management | An inventory method in which products are ordered and delivered at just the right time—when they are needed for patient care. The goal is minimizing wasted steps, labor, and cost. |

| manufacturer | A company that manufacturers or makes products such as drugs. |

| maximizing inventory turns | An inventory turn occurs when stock is completely depleted and reordered. Ideally, products should not sit on the shelf unused for long periods; they should be purchased and used many times throughout the course of a year. Inventory turns can be calculated by dividing the total purchases in a period by the value of physical inventory taken at a reasonable single point in time. |

Pharmaceutical Purchasing Groups

Drug Wholesaler and Prime Vendor Purchasing

Receiving and Storing Pharmaceuticals

Product Handling Considerations

Products Requiring Special Handling

Business Philosophies and Models Proper Disposal and Return of Pharmaceuticals Return of Other Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceutical Waste Management Role of the Food and Drug Administration Role of Manufacturers, Distributors, and Pharmacies |

|

P harmaceutical products flow into the pharmacy through a sophisticated and highly regulated distribution channel. Once they arrive in the pharmacy, these (often expensive) items become assets, and the inventory management process begins. Proper storage and availability of these products are essential to the delivery of patient care and the efficient operation of the pharmacy.

An effective pharmaceutical purchasing and inventory control system requires the understanding and active participation of all pharmacy staff. Certain staff members are often designated to be responsible for managing the pharmacy inventory and purchasing activities. Pharmacy technicians are often the principal buyers of medications and supplies for the pharmacy. Many hospitals strive to maintain accreditation of The Joint Commission. Its standards on medication management are intended to guide operational procedures and promote consistently safe practices related to the procurement, storage, dispensing, and administration of pharmaceuticals. Because pharmacy technicians are such an important part of preparation and dispensing of medications, their knowledge and performance are critical to the success of purchasing and inventory control procedures.

This chapter describes the basic principles of pharmaceutical purchasing and inventory control. It applies to all types of pharmacy settings, including institutional, home infusion, and ambulatory care pharmacy operations. For technicians who are interested in pursuing a specialized position within purchasing and inventory control, and for readers desiring more in-depth study, a reading list is included in the Resources section of this chapter.

Ordering Pharmaceuticals

Some pharmacies employ a dedicated purchasing agent to manage the procurement and inventory of pharmaceuticals. Others employ a more general approach, whereby several staff members are involved in ordering pharmaceuticals. The state-of-the-art practice involves the use of automated technology to manage the processes of purchasing and receiving pharmaceuticals from drug wholesalers. This technology includes using bar codes and handheld scanning devices for online procurement, purchase order generation, and electronic receiving processes (figure 19-1). Some pharmacies use sophisticated inventory management carousel systems to manage portions of their inventory (figure 19-2). Using computer and mechanical technology for these purposes has many benefits, including up-to-the-minute product availability information, comprehensive reporting capabilities, accuracy, reduced training time, and improved operational efficiency. It also encourages compliance with various pharmaceutical purchasing contracts.

The National Drug Code

All commercial pharmaceutical manufacturers are required to register pharmaceuticals with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This FDA Drug Registration and Listing System (DRLS) is a database that utilizes a unique identification number, called the National Drug Code (or NDC number), to identify drug products that are intended for human consumption or use.

The NDC number appears on the manufacturer’s label and follows a 10-digit format, either 4-4-2 (four digits-four digits-two digits), 5-3-2, or 5-4-1, as shown in figure 19-3. The first set of digits identifies the specific drug manufacturer or labeler of the product and is assigned by the FDA. The next segment of digits is the product code, denoting the formulation, dosage form, and strength. The final segment identifies package type and size. The NDC number is particularly useful in precisely identifying drug products in the processes of dispensing, placing orders, and addressing drug recalls.

Figure 19–1. Handheld bar code scanning device.

Figure 19–2. Medication dispensing carousel.1

The Formulary System

Most hospitals and health care systems develop a list of medications that may be prescribed for patients in the institution or health care system. This list, usually called a formulary, serves as the cornerstone of the purchasing and inventory control system. The formulary is developed and maintained by a committee of medical and allied health staff called the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. This group generally comprises physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and administrators, although individuals from other disciplines may be present, such as dieticians, risk managers, and case managers. They collaborate to ensure that the safest, most effective, and least costly medications are included on the formulary. The products on the hospital formulary dictate what the hospital pharmacy should keep in inventory.

Third-party prescription pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs) also establish plan-specific formularies for their ambulatory patients. In serving their patients, community (retail) pharmacy staff frequently encounter drug formularies that are specific to particular insurance plans; they adjust their inventory accordingly. Most retail pharmacies do not restrict items in their inventory as a hospital pharmacy does because, in this setting, inventories are largely dependent on the dynamic needs of their patient population and, to some degree, their patients’ respective insurance plans. Therefore, the concept of formulary management differs greatly depending on the pharmacy setting (e.g., hospital versus retail pharmacy).

Formats and Updates. The hospital formulary is usually available electronically and/or in print form. The formulary is produced exclusively for health practitioners involved in prescribing, dispensing, administering, and monitoring medications. It is generally formatted to inform users of product availability, the appropriate therapeutic uses, and recommended dosing and administration of medications. Some formularies are organized alphabetically by the generic drug’s name, which is typically cross-referenced with the trade name products; others may be organized by therapeutic drug class. In most cases, the drug storage areas in the pharmacy are arranged alphabetically, by either the generic or trade name of the drug. Therefore, the formulary can help the pharmacy technician determine whether a product is stocked in the pharmacy and where it would be located.

It is important for pharmacy technicians to understand how the formulary is updated and, how and when changes to the formulary are communicated to the staff. Drugs are added and deleted from the formulary on a regular basis, but the frequency of these changes varies among organizations. Printed formularies are typically updated every 12 to 18 months. Loose-leaf formularies and those maintained online can be updated continuously in a more timely manner, whereas bound formulary handbooks rely on supplementary updates or publication of serial editions. A sample formulary listing is shown in figure 19-4.

Other important information that may be available in the formulary, specified under each listing, is the dosage form, strength, and concentration; package size(s); common side effects; and administration instructions. Some institutions also indicate the actual or relative cost of a given item. When selecting a drug product from inventory, the technician must consider all product characteristics, such as name, dosage form, strength or concentration, and package size. Detailed review and consideration of each listing helps minimize errors in product selection.

Non-Formulary Protocol. In keeping with the standards and controls created by an organized formulary system, most hospitals employ a formal procedure to manage appropriate drug use. The use of products that are not on the official hospital formulary is considered non-formulary drug use. Typically, when a prescriber orders a non-formulary product, the pharmacist requests verbal or written justification for its use and challenges the request, as appropriate, if a comparable or therapeutically equivalent product is available on the hospital formulary. In certain cases, the utilization of a nonformulary product is warranted when its benefit is believed to be superior to that of the other alternative formulary items that may exist (usually for a patient-specific or diseasespecific reason).

The pharmacy’s non-formulary procedure may or may not restrict the use of various dosage forms of a given chemical entity, so pharmacy technicians need to understand the policy in place at their specific institutions. The P&T committee regularly reviews non-formulary drug utilization to identify trends and review concerns, and this process may prompt the addition of new products to the formulary over time.

Figure 19–4. Sample formulary listing.

Pharmaceutical Purchasing Groups

Most health system pharmacies are members of a group purchasing organization (GPO). The GPO contracts with manufacturers to purchase pharmaceuticals at discounted prices, in return for a guaranteed minimum purchase volume. Hospitals, independent community pharmacies, and other retail chain pharmacies typically become members of a GPO to leverage buying power and take advantage of the lower prices that manufacturers offer to the GPOs.

Purchasing contracts can involve sole-source or multisource products. Sole-source branded products are available from only one manufacturer, whereas multisource generic products are available from numerous manufacturers. Although sole-source products may be produced by only one manufacturer, they may be included in what is known as a competitive market basket. For example, the echinocandin antifungal agent class contains all of the sole-source branded competing products in the market basket, including caspofungin (Cancidas), micafungin (Mycamine), and anidulofungin (Eraxis).

GPOs negotiate purchasing contracts that are mutually favorable to members of the group and to manufacturers. In addition to lower prices, pharmacies also benefit because this reduces the time staff spent establishing and managing purchasing contracts with product vendors. A GPO guarantees the price of pharmaceuticals over the established contract period, which may be one year or more. With the purchase price predetermined, the pharmacy can order the product directly from the manufacturer or from a wholesale supplier.

Occasionally, manufacturers are unable to supply a given product that the pharmacy is buying on contract, which may require the pharmacy to buy or substitute a competing product that is not on contract at a higher cost. Most purchasing contracts include provisions that protect the pharmacy from incurring additional expenses in the event this occurs. Generally, the manufacturer is responsible for rebating the difference in cost back to the pharmacy when this occurs. Therefore, it is important that the pharmacy technician documents any resulting off-contract purchases and communicates the information to the pharmacist-in-charge for reconciliation with the contracted product vendor.

Direct Purchasing

Direct purchasing from a manufacturer involves the execution of a purchase order (PO) from the pharmacy to the manufacturer of the drug. A purchase order is a document, executed by a purchaser and forwarded to a supplier, that is considered a legal offer to buy products or services. It usually indicates descriptive information, such as the item description, package size, desired quantity, and listed price. The advantages of direct purchasing include not having to pay handling fees to a third-party wholesaler, the ability to order on an infrequent basis (e.g., once a month), and a less demanding system for monitoring inventory. Some disadvantages include the following: a large storage capacity is needed; a large amount of cash is invested in inventory; the pharmacy’s return/credit process becomes more complicated; and staff resources required in the pharmacy and accounts payable department to prepare, process, and pay purchase orders to more companies are increased. Other disadvantages include the likelihood that the manufacturer’s warehouse is not local in relation to the pharmacy, which creates a dependency on the shipping firms used by the manufacturers to ship products reliably. In addition, the delivery schedule is often unpredictable or not available on weekends, and there may be delays in delivery.

For most pharmacies, the disadvantages of direct ordering outweigh the advantages. As a result, most pharmacies primarily purchase through a drug wholesaler. The wholesaler (also known as distributor) usually operates a large-scale warehouse in various geographic regions and exists to help bring pharmaceutical products closer to the market. This helps local pharmacies buy in smaller quantities and receive drugs in a timely manner (i.e., often same day), as opposed to ordering products directly from the manufacturer, in which case shipping and product delivery may take many days. It helps pharmacies manage their expenses and more effectively turn over their shelf inventories. Some drugs, however, can only be purchased directly from the manufacturers. These products generally require unique control or storage conditions and may be very costly, relative to others. An example is Botulinum Immune Globulin Intravenous (also known as BabyBIG®. This product is used to treat suspected infant botulism and must be ordered under a strict protocol from the Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program (IBTPP), operated by the State of California. Once the BabyBIG® treatment indication is established and approved (on a patient-by-patient basis), the ordering pharmacy must complete an invoice and purchase agreement in order to initiate shipment of this life-saving product. In 2010, the current price per vial of BabyBIG® was approximately $45,300. Once purchased, funds must be wired to the IBTPP within five business days to satisfy the terms of the order. Consequently, most pharmacies use a combination of direct purchases from manufacturers and drug wholesalers.

Drug Wholesaler and Prime Vendor Purchasing

Purchasing from a drug wholesaler permits the acquisition of drug products from different manufacturers through a single vendor. When a health system pharmacy agrees to purchase most (e.g., 90 to 95%) of its pharmaceuticals from a single wholesale company, a prime vendor arrangement is established, and, customarily, a contract between the pharmacy and the drug wholesaler is developed. Usually, wholesalers agree to deliver 95 to 98% of the items on schedule and offer a 24-hour/7-day-per-week emergency service. They also provide the pharmacy with electronic order entry/receiving devices, a computer system for ordering, bar coded shelf stickers, and a printer for order confirmation printouts. They may also offer a highly competitive discount (minus 1 to 2%) below product cost/contract pricing and competitive alternate contract pricing.

Some wholesalers offer even larger discounts to pharmacies that may prefer a prepayment arrangement. In these situations, the wholesaler monitors the aggregate purchases of the pharmacy (e.g., a rolling three-month average) and bills the pharmacy this amount in advance (prepayment). This may be attractive to both the wholesaler and the pharmacy because it creates larger cash flow and investment capital for the wholesaler while saving the organization money on its pharmaceutical purchases through discounted pricing.

These wholesaler services make the establishment of a prime vendor contract appealing and result in the following advantages: more timely ordering and delivery, less time spent creating purchase orders, fewer inventory carrying costs, less documentation, computer-generated lists of pharmaceuticals purchased, and overall simplification of the credit and return process. Purchasing through a prime vendor customarily allows for drugs to be received shortly before use, supporting a just-intime ordering philosophy (which is described later in the chapter). Purchasing from a wholesaler is a highly efficient and cost-effective approach toward pharmaceutical purchasing and inventory management.

Borrowing Pharmaceuticals

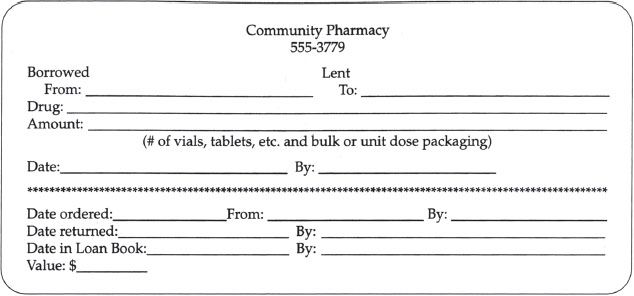

No matter how effective a purchasing system is, there are times when the pharmacy must borrow drugs from other pharmacies. Most pharmacies have policies and procedures addressing this situation. Borrowing or lending drugs between pharmacies is usually restricted to emergency situations and limited to authorized staff. Borrowing is also limited to products that are commercially available, thus eliminating items such as compounded products or investigational medications. Most pharmacies have developed forms to document and track merchandise that is borrowed or loaned (figure 19-5). These forms also help staff document the details that are needed to prevent errors in the transactions.

Figure 19–5. Sample borrow/lend form.

The pharmacy department’s borrow and lend policies and procedures should provide detailed directions on how to borrow and lend products, which products may be borrowed or loaned, sources for the products, and reconciliation of borrow and lend transactions (the payback process). Securing the borrowed item may require the use of a transport or courier service or may include the use of security staff or other designated personnel. Some states have established strict limits on the quantities of products that can be borrowed or loaned under casual sale protocol, such as interpharmacy borrowing, lending, or even donating to a charity cause such as a legitimate medical mission. This information is vital for pharmacy technicians to understand so that they can fulfill their responsibility when borrowing or lending products.

RX for Success

Purchasing and inventory staff should keep up with returning borrowed items in order to remain in good standing with those pharmacies that participate in this practice. Reconciliation of these items should be done at least quarterly.

Receiving and Storing Pharmaceuticals

One of the most useful experiences for a new pharmacy technician is to observe the way that the pharmacy department receives pharmaceuticals. This experience is useful for a number of reasons:

It helps the pharmacy technician become familiar with the various processes involved with the ordering and receiving of pharmaceuticals.

It helps the pharmacy technician become familiar with the various processes involved with the ordering and receiving of pharmaceuticals.

It helps the technician become familiar with formulary items.

It helps the technician become familiar with formulary items.

It demonstrates the system used to ensure that only formulary items are put into inventory.

It demonstrates the system used to ensure that only formulary items are put into inventory.

It familiarizes the technician with the various locations in which drugs are stored.

It familiarizes the technician with the various locations in which drugs are stored.

Receiving is one of the most important parts of the pharmacy operation. A poorly organized and executed receiving system can put patients at risk and elevate health care costs. For example, if the wrong concentration of a product were received in error, it could lead to a dosing error or a delay in therapy. Misplaced products or out-ofstock products also jeopardize patient care, as well as the efficiency of the department—both are undesirable and costly outcomes. To avoid these unfavorable outcomes, pharmacy technicians need to become familiar with the process of receiving and storing pharmaceuticals.

The Receiving Process

Some pharmacies create processes whereby the person receiving pharmaceuticals is different from the person ordering them. This process is especially important for controlled substances, because it effectively establishes a check in the system to minimize potential drug diversion opportunities. Drug diversion is the theft of a pharmaceutical by an individual for illicit personal use or gain.

In a reliable and efficient receiving system, the receiving personnel verify that the shipment is complete and intact (i.e., they check for missing or damaged items) before putting items into circulation or inventory. The receiving process begins with the verification of the boxes containing pharmaceuticals delivered by the shipper. The person receiving the shipment begins the process by verifying that the name and address on the boxes are correct and that the number of boxes matches the shipping manifest. Many drug wholesalers use rigid plastic totes because they protect the contents of each shipment better than foam or cardboard boxes. These totes are also environmentally friendly; they are returned to the wholesaler for cleaning and reuse. Each tote should be inspected for gross damage.

Products with a cold storage requirement (i.e., refrigeration or freezing) should be processed first. The shipper is responsible for taking measures to ensure that the cold storage environment is maintained during the shipment process and generally packages these items in a shippable foam cooler that includes frozen cold packs to keep products at the correct storage temperature during shipment.

Figure 19–6. Electronic purchase order.

Receiving personnel play a critical role in protecting the pharmacy from financial responsibility for products damaged in shipment, products not ordered, and products not received. Any obvious damage or other discrepancies with the shipment, such as a breach in the cold storage environment or an incorrect product, should be noted on the shipping manifest, and, if warranted, that part of the shipment should be refused. Ideally, identifying gross shipment damage or incorrect tote counts should be performed in the presence of the delivery person and should be well documented when signing for the order. Other problems identified after delivery personnel have left, such as mispicks (i.e., products sent in error by the vendor), product dating, or internally damaged goods, must be resolved according to the vendor’s policies. Most vendors have specific procedures to follow in reporting and resolving such discrepancies. The technician can also identify packages that are received containing broken tablets, defective seals, etc., so that the wholesaler/shipper can be alerted to weaknesses in the delivery system. Quality issues can often be identified first by the technicians working the receiving area.

The next step of the receiving process entails checking the newly delivered products against the receiving copy of the purchase order. This generally occurs after the delivery person has left. A purchase order, created when the order is placed, is a complete list of the items that were ordered. Some pharmacies may still use a traditional paper purchase order. However, the state-of-the-art practice employs electronic, Web-based technology to place orders with respective wholesale distributors (figure 19-6). In this case, the order is transmitted and received in an instant, and the wholesaler’s inventory of particular products is available in near real-time. This technology allows for more efficient operations and effective communication between the pharmacy and wholesaler and simplifies order reconciliation and billing processes.

The contemporary practice of receiving employs bar code technology, which simplifies the process of receiving—to the extent that invoice reconciliation against the contents of shipment totes can be accomplished with a bar code scanner.

The person responsible for checking products into inventory uses the receiving copy of the purchase order that is included in each wholesaler tote to ensure that the products ordered have been received. The name, brand, dosage form, size of the package, concentration or strength, and quantity of product must match the purchase order.

Once the accuracy of the shipment is confirmed, the packing list is generally signed and dated by the person receiving the shipment. At this point, the product’s expiration date should be checked to ensure that it meets the department’s minimum expiration date requirement. Frequently, departments require that products received have a minimum shelf life of 6 months remaining before they expire.

Bar Code Medication Administration (BCMA) is a novel technology that has slowly emerged in health care institutions. It is meant to improve the safety of medication administration at the bedside and improve medication administration documentation in the patient’s electronic health record.

Figure 19–7. Receipt of pharmaceutical on blank paper.

Figure 19–8. Receipt of pharmaceutical on packing slip/invoice.

If a hospital uses a BCMA system, it is critical that each bar code be scanned at the time that each product is received. This ensures that the product bar code is in the BCMA system so that it can scan correctly when it gets to the bedside. This applies even if the product has been received before from the same manufacturer. Some bar codes contain lot and expiration date information, which could change with each manufacturer batch production. In the event that a bar code does not scan, it is customary for the receiving technician to add the item to the BCMA system manually or to overlay an internal bar code on the product prior to shelving it. It is noteworthy to mention that, on occasion, the manufacturer/wholesaler may inadvertently ship an excess quantity of an ordered product to the pharmacy. The ethical response is to immediately notify the manufacturer or wholesaler of this situation and arrange for the return of any excess quantity.

If a pharmacist or pharmacy technician other than the receiving technician removes a product from a shipment before it has been properly received and cannot locate the receiving copy of the purchase order, a written record of receipt should be created. This is done by listing the product, dosage form, concentration/strength, package size, and quantity on a blank piece of paper (figure 19-7) or on the supplier’s packing slip/invoice and checking off the line item received (figure 19-8). In both cases, the name of the person receiving the product should be included, and the document should be given to the receiving technician, to avoid confusion and an unnecessary call to the wholesaler or manufacturer.

The Storing Process

Once the product has been received properly, it must be stored properly. Depending on the size and type of the pharmacy operation, the product may be placed in a bulk central storage area or into the active dispensing area of the pharmacy. In any case, the expiration date of the product should be compared with that of the products currently in stock. Products already in stock that have expired should be removed. Products that will expire in the near future should be highlighted and placed in the front of the shelf or bin. This is a common practice known as stock rotation. The newly acquired products generally have longer shelf lives and should be placed behind packages that will expire before them.

Stock rotation is an important inventory management principle that encourages the use of products before they expire and helps prevent the use of expired products and waste.

Stock rotation is an important inventory management principle that encourages the use of products before they expire and helps prevent the use of expired products and waste.

Table 19-1 identifies the optimal storage temperatures and humidity.

The use of automated dispensing devices in inpatient hospital nursing units, clinics, operating rooms, and emergency rooms has facilitated the use of computers for inventory management. Similar devices are evolving in retail pharmacy and hold promise for not only making the dispensing process safer and more efficient, but also serving to assist in inventory management. These devices are essentially repositories, or pharmaceutical vending machines, for medications that are dispensed directly from a patient care area.

A variety of manufacturers of automated dispensing devices are in the current market. The Pyxis Medstation and Omnicell are common examples of devices available to institutions. These machines generally are networked via a dedicated computer file server within the facility, and they allow both unit-dose and bulk pharmaceuticals to be stocked securely on a given patient care unit location. Each unit’s inventory is configurable and allows for variation and flexibility from device to device, depending on the unit’s location.

Product Handling Considerations

Pharmacy technicians usually spend more time handling and preparing medications than the pharmacists. This presents pharmacy technicians with the critical responsibility of assessing and evaluating each product from both a content and labeling standpoint. It also provides the technician with an opportunity to confirm that the receiving process was performed properly.

Table 19–1. Defined Storage Temperatures and Humidity†

| Freezer | -25º to -10º C | -13º to 14º F |

| Cold (Refrigerated) | 2º to 8º C | 36º to 46º F |

| Cool | 8º to 15º C | 46º to 59º F |

| Room Temperature | The temperature prevailing in a working area. | |

| Controlled Room Temperature | 20º to 25º C | 68º to 77º F |

| Warm | 30º to 40º C | 86º to 104º F |

| Excessive Heat | Any temperature above 40ºC (104º F) | |

| Dry Place | A place that does not exceed 40% average relative humidity at controlled room temperature or the equivalent water vapor pressure at other temperatures. Storage in a container validated to protect the article from moisture vapor, including storage in bulk, is considered a dry place. | |

† United States Pharmacopeia 26/The National Formulary 21, pp. 9–10;2003. United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc., Rockville, MD.

Just as checking the product label carefully when a prescription or medication order is filled is important, taking the same care when receiving pharmaceuticals and accurately placing them in their storage location are essential. The pharmacy technician should read product packaging carefully rather than relying on the general appearance of the product (e.g., packaging type, size or shape, color, logo), because a product’s appearance can change frequently and may be similar to that of other products. Technicians play a vital role in minimizing dispensing errors that can occur because of human fallibility. They are generally the first in a series of checks involved in an accurate dispensing process.

When performing purchasing or inventory management roles, the technician must pay close attention to the product’s expiration date. For liquids or injectable products, the color and clarity of the items should also be checked for consistency with the product standard. Products with visible particles, an unusual appearance, or a broken seal should be reported to the pharmacist.

Look-Alike/Sound-Alike Products

Because pharmacy technicians handle so many products each day, they are in an ideal position to identify packaging and storage issues that could lead to errors. Technicians should pay close attention to these three main issues of product similarity:

1. Similar drug names. Various drugs with similar names (e.g., niCARdipine, NIFEdipine, cycloSPORINE, cycloSERINE) can cause problems when stored in an immediately adjacent shelf position. Although the use of tall man lettering can help draw attention to the dissimilarities in the product name, extra precaution in shelf positioning may be warranted (figure 19-9).

2. Similar package sizes. Stocking products of similar name, color, shape, and size can result in error if someone fails to read the label carefully. Sometimes the company name or logo is emphasized on the label instead of the drug name, concentration, or strength (figure 19-10). Pharmacy repackaged items often look the same as a result of the nature of the packaging process implemented.

3. Similar label format. Storing products that are similar in appearance adjacent to one another can result in error if someone fails to read the label (figure 19-11).

The convention of labeling pharmaceuticals with tall man lettering is also known as mixed case labeling, and it is an important tactic employed in the interest of calling attention to similarities in drug names. Research on this approach has demonstrated effectiveness in distinguishing similarities and preventing look-alike, sound-alike drug mix-ups2.

The convention of labeling pharmaceuticals with tall man lettering is also known as mixed case labeling, and it is an important tactic employed in the interest of calling attention to similarities in drug names. Research on this approach has demonstrated effectiveness in distinguishing similarities and preventing look-alike, sound-alike drug mix-ups2.