Patient Story

A 52-year-old woman developed acute shortness of breath 3 weeks after a hysterectomy. She denied leg pain or swelling. She has no chronic medical problems and takes no medications. Her pulse is 105 beats/min, respiratory rate is 20 breaths/min, and the rest of her examination is unremarkable. She had an elevated hemidiaphragm on chest X-ray (CXR). These findings placed her at moderate risk for pulmonary embolism (PE) based on the Geneva score. Chest CT demonstrated a moderate-sized PE similar to the one shown in Figure 57-1. She was treated with anticoagulation without complications.

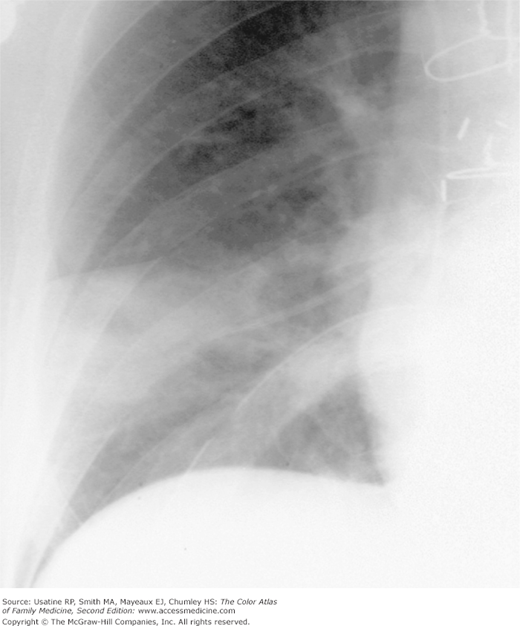

Figure 57-1

CXR showing a wedge-shaped pulmonary infarction with the base on the pleural surface and the apex at the tip of a pulmonary artery catheter; the catheter caused the occlusion of a peripheral artery. (From Miller WT Jr. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:272, Figure 5-61. Copyright 2006.)

Introduction

Epidemiology

- Population estimate of the age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of DVT is 48 per 100,000 and 69 per 100,000 for PE; the incidence increases with age.1

- PEs are noted as incidental findings in 1% to 4% of chest CT studies.2

- One metaanalysis concluded that nearly 1 in every 4 to 5 patients presenting with an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has a PE; presenting signs and symptoms did not distinguish patients with and without PE.3

- In a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of patients on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, the pooled rates of symptomatic DVT were 0.63% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47% to 0.78%) following knee arthroplasty and 0.26% (95% CI, 0.14% to 0.37%) following hip arthroplasty. The pooled rates for PE were 0.27% (95% CI, 0.16% to 0.38%) following knee arthroplasty and 0.14% (95% CI, 0.07% to 0.21%) following hip arthroplasty.4

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- PE is most commonly caused by embolization of a thrombus from a proximal leg or pelvic vein that enters the pulmonary artery circulation and obstructs a vessel. PE may also be caused by:1

- An upper-extremity thrombus (from indwelling catheters or pacemakers) (Figure 57-1).

- Fat embolus (following surgery or trauma).

- Hair/talc/cotton embolus (from intravenous drug use).

- Amniotic fluid embolus (from a tear at the placental margin in a pregnant woman).

- An upper-extremity thrombus (from indwelling catheters or pacemakers) (Figure 57-1).

- PE results from vascular endothelial injury, which promotes platelet adhesion, blood flow stasis, and/or hypercoagulation causing more coagulants to accumulate than usual and resulting obstruction. Although most PEs are asymptomatic and do not alter physiology, PE can cause:

- Increased pulmonary, vascular, and airway resistance (from obstruction of vessels or distal airways).

- Impaired gas exchange (from increased dead space and right to left shunting).

- Alveolar hyperventilation (from stimulation of irritant receptors).

- Decreased pulmonary compliance (from lung edema, hemorrhage, or loss of surfactant).

- Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction (from increased pulmonary vascular resistance, increased RV wall tension, and reduced right coronary artery flow).

- Only approximately 10% of emboli cause pulmonary infarction; most PEs are multiple and involve the lower lobes.5

- Increased pulmonary, vascular, and airway resistance (from obstruction of vessels or distal airways).

Risk Factors

- Surgery (odds ratio [OR], 21.7; 95% CI, 9.4 to 49.9).

- Trauma (OR, 12.7; 95% CI, 4.1 to 39.7).

- Hospital or nursing home confinement (OR, 8.0; 95% CI, 4.5 to 14.2).

- Malignant neoplasm with (OR, 6.5; 95% CI, 2.1 to 20.2) or without (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.9 to 8.5) chemotherapy.

- Central venous catheter or pacemaker (OR, 5.6; 95% CI, 1.6 to 19.6).

- Superficial vein thrombosis (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.8 to 10.6). A recent study found a slightly higher OR, 6.3 (95% CI, 5.0 to 8.0) for DVT and 3.9 (95% CI, 3.0 to 5.1) for PE.7

- Neurologic disease with extremity paresis (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.3 to 7.4).

- Other risk factors for PE include hormonal treatment (i.e., combined estrogen/progestogen oral contraceptives [OCs] or menopausal hormone therapy), pregnancy, obesity, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, immobility, bed rest for more than 3 days, and clotting disorders. In a Danish population study, the risk of venous thrombosis in current users of combined OCs decreased with duration of use (OR <1 year 4.17 [95% CI, 3.73 to 4.66]; OR 1 to 4 years 2.98 [95% CI, 2.73 to 3.26] and OR >4 years 2.76 [95% CI, 2.53 to 3.02]) and decreasing oestrogen dose.8 OCs with desogestrel, gestodene, or drospirenone were associated with a significantly higher risk of venous thrombosis than those with levonorgestrel, while progestogen-only pills and hormone-releasing intrauterine devices were not associated with an increased risk.

- Genetic predisposition includes factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutations.

- Use of an antipsychotic agent (particularly atypical antipsychotics) increased risk of DVT in a population nested case-control study (OR 1.32, 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.42).9

Diagnosis

A history and physical examination should be completed to assess risk factors and determine whether the patient is clinically stable. If unstable (e.g., hemodynamic instability [including systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, or a drop of 40 mm Hg], syncope, severe hypoxemia, or respiratory distress), thrombolytic therapy should be considered (Figure 57-1).2,10

Diagnostic strategy begins with the determination of a patient’s (pretest) probability of PE using a clinical decision rule (Figure 57-2). The two most frequently used rules are the Geneva and the Wells score.11,12 Online calculators are available for the Wells score (http://www.mdcalc.com/wells-criteria-for-pulmonary-embolism-pe/). The Geneva score appears to be the most consistent across experience of examiner;13 and the revised Geneva scoring system performs as well as the Wells and does not require laboratory testing or imaging.14 A score of 0 to 3 indicates a low probability of PE (8%); 4 to 10 indicates intermediate probability of PE (28%); and greater than 10 indicates a high probability of PE (74%). The revised Geneva score is derived by summing the following points:

- Age older than 65 years (+1).

- Previous DVT or PE (+3).

- Surgery or fracture within 1 month (+2).

- Active malignant condition (+2).

- Unilateral lower limb pain (+3).

- Hemoptysis (+2).

- Heart rate 75 to 94 beats/min (+3) or equal to or greater than 95 beats/min (+5).

- Pain on lower-limb deep venous palpation and unilateral edema (+4).

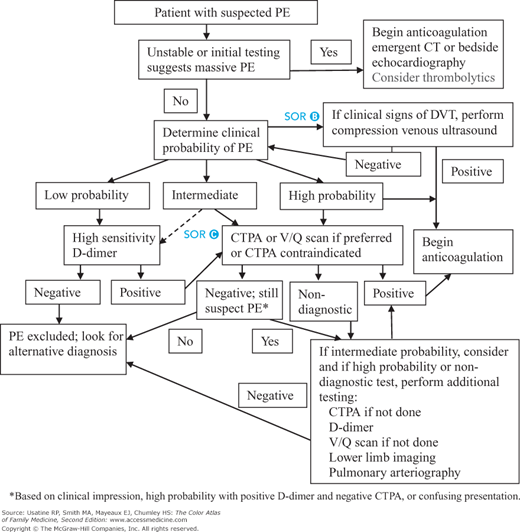

Figure 57-2

Approach to the patient with suspected pulmonary embolus. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; CTPA, computed tomographic pulmonary arteriography; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; V/Q, ventilation-perfusion. (Dotted lines indicate differences in guidelines). (Information from Fesmire FM, Brown MD, Espinosa JA, et al.; American College of Emergency Physicians. Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(6):628-652; Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosis and Treatment. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2011 Mar. 93 p. Available at http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=32482&search= pulmonary+embolism.)

The Wells score is derived by summing the factors below; a score less than 2 indicates a low probability of PE (15%); 2 to 6 indicates intermediate probability of PE (29%); and greater than 6 indicates a high probability of PE (59%). Alternatively, the Wells score can be dichotomized as PE less likely or likely (the latter with score >4):2

- Clinically suspected DVT (+3).

- Alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE (+3).

- Tachycardia (+1.5).

- Immobilization/surgery in previous 4 weeks (+1.5).

- History of DVT or PE (+1.5).

- Hemoptysis (+1.0).

- Malignancy (treatment for within 6 months, palliative) (+1.0).

Patients with a high pretest probability of PE or high risk because of comorbidities (e.g., pulmonary hypertension) should be started on anticoagulation during the workup.2,10

- Dyspnea—The most common symptom; tachycardia is the most common sign. Sudden onset of dyspnea is the best single predictor (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] 2.7).

- Chest pain—May be caused by a small, peripheral PE with pulmonary infarction.

- Other signs—Include fever, neck vein distention, and accentuated pulmonic component of the second heart sound.

- Massive PE—May present with shock, syncope, and cyanosis.

- The combination of clinical decision rules and sensitive plasma D-dimer is used to rule out a PE (sensitive but not specific).15,16 SOR B The test is suggested for patients with a low or moderate probability of a PE: if low probability and negative (<500 ng/mL), there is only approximately a 0.4% chance that the patient has a PE.14 If low or intermediate probability, a negative D-dimer concentration is associated with a posttest probability of PE below 5% (negative likelihood ratio [LR−] 0.08 [0.04 to 0.18]).17 Of patients with a PE, 90% will have a value greater than 500 ng/mL. Use of an age-adjusted D-dimer (patient’s age × 10 mcg/L) was shown in one study to increase the percentage of patients in whom PE could be safely excluded (from 13% to 14% to 19% to 22%).18 If the D-dimer is positive, further testing is needed (Figure 57-2).2

- An ECG may be indicated to search for alternative diagnoses. The most frequent, sensitive, and specific ECG finding for PE is T-wave inversion in leads V1 to V4, which is indicative of RV strain. Other findings include tachycardia, new-onset atrial fibrillation or flutter, S in Lead I, Q and inverted T in lead III, and a QRS axis greater than 90 degrees.

- Arterial blood gas is obtained if clinically indicated. A platelet count should be obtained prior to initiation of fondaparinux.10

- CXR is often nonspecific; dyspnea with a near normal CXR should suggest PE. Findings that may be seen on CXR include:

- Triad of basal infiltrate, blunted costophrenic angle, and elevated hemidiaphragm.

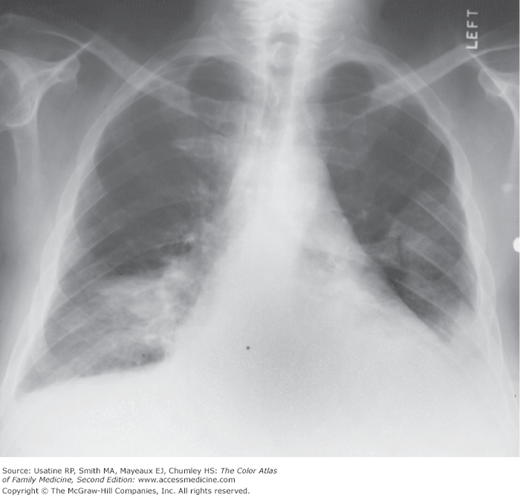

- Infiltrates similar to pneumonia (Figure 57-3) that may be diagnosed using CT (Figure 57-4).

- A peripheral wedge-shaped density (Figure 57-1).

- Decreased vascular markings (Figure 57-5).

- When a patient has an intermediate or high PE probability score, PE is confirmed by a positive CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) or high-probability lung scan, and ruled out by a negative CTPA or normal lung scan (Figure 57-1). The American College of Radiology (ACR) and Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommend CTPA over ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan for patients with suspected PE, unless the former is contraindicated or nondiagnostic (Figure 57-1).2,19 CT (Figure 57-4) can also provide evidence of alternate diagnoses.

- A V/Q scan is considered the initial test for patients with high probability of PE who have renal insufficiency or dye allergy. A high-probability scan for PE (positive predictive value of 90%) has 2 or more segmental perfusion defects with normal ventilation.

- For pregnant women with suspected PE, the American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology recommend CXR as the initial study followed by lung scintigraphy (V/Q scan) if the CXR is normal, and CTPA if the V/Q scan is nondiagnostic.20

- If the CTPA or lung scan is nondiagnostic, a leg ultrasound with compression is usually performed. If positive for a DVT, proceed with treatment as below. If normal or nondiagnostic, other testing such as a pulmonary angiogram is suggested (Figure 57-1).

- Pulmonary angiography is generally reserved for patients with nondiagnostic CTPA, lung scans, or leg ultrasound, and for patients who will undergo embolectomy or catheter-directed thrombolysis. ACR also recommends pulmonary angiography in circumstances where a specific diagnosis (i.e., PE) is considered necessary for the proper patient management and before placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter.10 An intraluminal filling defect may be seen along with truncated arteries associated with regions of diminished perfusion (Figure 57-6).

- Although MRI is not indicated in the routine evaluation of suspected PE, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is used in certain centers with particular interest and expertise, and in patients in whom contrast administration for CTPA or pulmonary angiography is thought to be contraindicated because of renal failure, prior reaction to iodinated contrast, pulmonary hypertension, or for other reasons.19

- Triad of basal infiltrate, blunted costophrenic angle, and elevated hemidiaphragm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree