Chapter 23 Psychological medicine

Introduction

Epidemiology (Box 23.1)

![]() Box 23.1

Box 23.1

The approximate prevalence of psychiatric disorders in different populations

| Approximate percentage | |

|---|---|

Community | 20 |

Neuroses | 16 |

Psychoses | 0.5 |

Alcohol misuse | 5 |

Drug misuse | 2 (an underestimate) |

(total in community 20% due to co-morbidity) |

|

Primary care | 25 |

General hospital outpatients | 30 |

General hospital inpatients | 40 |

The psychiatric history

As in any medical specialty, the history is essential in making a diagnosis. It is similar to that used in all specialties but tailored to help to make a psychiatric diagnosis, determine possible aetiology, and estimate prognosis. Data may be taken from several sources, including interviewing the patient, a friend or relative (usually with the patient’s permission), or the patient’s general practitioner. The patient interview also enables a doctor to establish a therapeutic relationship with the patient. Box 23.2 gives essential guidance on how to safely conduct such an interview, although it is unlikely that a patient will physically harm a healthcare professional. When interviewing a patient for the first time, follow the guidance outlined in Chapter 1 (see pp. 10–12).

![]() Box 23.2

Box 23.2

The essentials of a safe psychiatric interview

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Components of the history are summarized in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 Summary of the components of the psychiatric history

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

Reason for referral | Why and how the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

Present illness | How the illness progressed from the earliest time at which a change was noted until the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

Past psychiatric history | Prior episodes of illness, where were they treated and how? Prior self-harm |

Past medical history | Include emotional reactions to illness and procedures |

Family history | History of psychiatric illnesses and relationships within the family |

Personal (biographical) history | Childhood: Pregnancy and birth (complications, nature of delivery), early development and attainment of developmental milestones (e.g. learning to crawl, walk, talk). School history: age started and finished; truancy, bullying, reprimands; qualifications |

Adulthood: Employment (age of first, total number, reasons for leaving, problems at work), relationships (sexual orientation, age of first, total number, reasons for endings of relationships), children and dependants | |

Reproductive history | In women: include menstrual problems, pregnancies, terminations, miscarriages, contraception and the menopause |

Social history | Current employment, benefits, housing, current stressors |

Personality | This may help to determine prognosis. How do they normally cope with stress? Do they trust others and make friends easily? Irritable? Moody? A loner? This list is not exhaustive |

Drug history | Prescribed and over-the-counter medication, units and type of alcohol/week, tobacco, caffeine and illicit drugs |

Forensic history | Explain that you need to ask about this, since ill-health can sometimes lead to problems with the law. Note any violent or sexual offences. This is part of a risk assessment. Worst harm they have ever inflicted on someone else? Under what circumstances? Would they do the same again were the situation to recur? |

Systematic review | Psychiatric illness is not exclusive of physical illness! The two may not only co-exist but may also have a common aetiology |

The mental state examination (MSE)

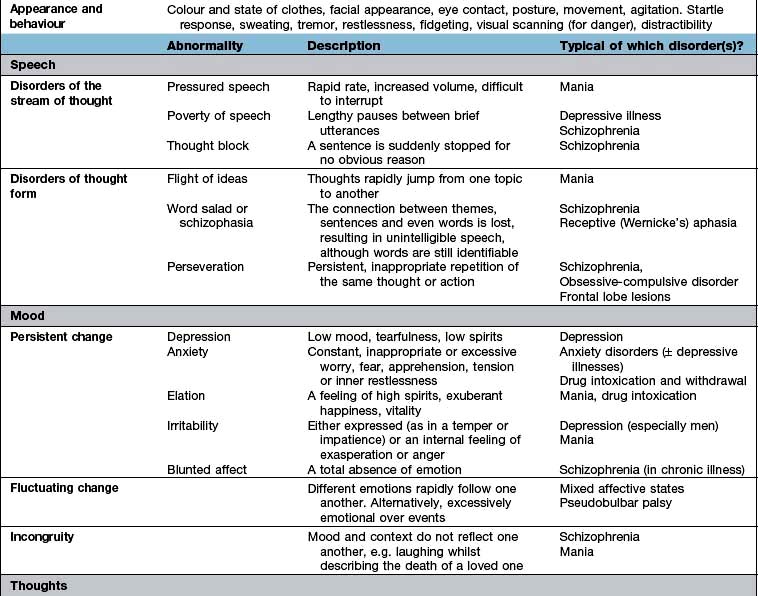

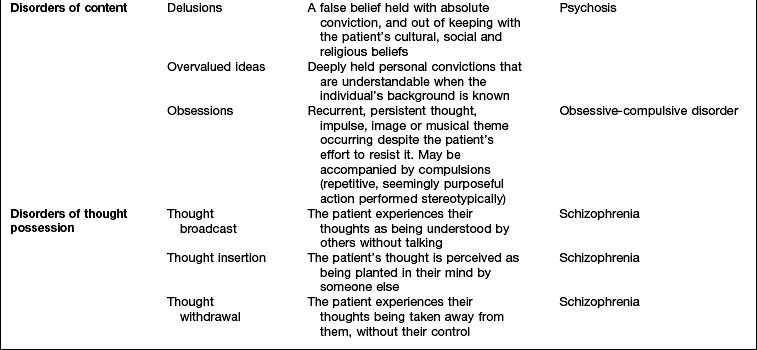

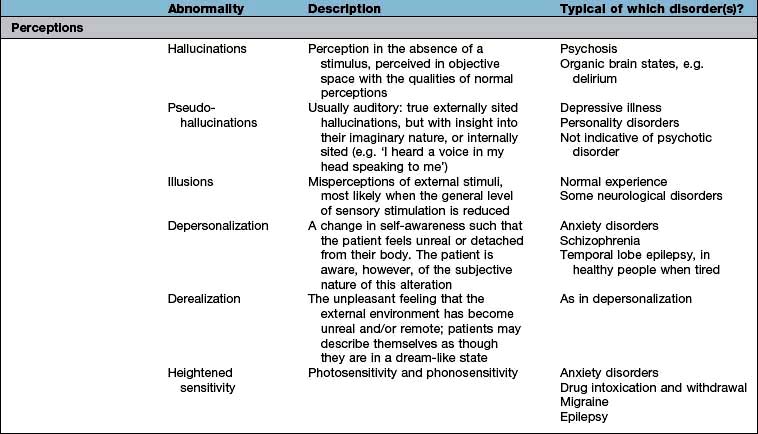

The history will already have assessed several aspects of the MSE, but the interviewer will need to expand several areas as well as test specific areas, such as cognition. The MSE is typically followed by a physical examination and is concluded with an assessment of insight, risk and a formulation that takes into account a differential diagnosis and aetiology. Each domain of the MSE is given below; abnormalities that might be detected and the disorders in which they are found are summarized in Table 23.2. The major subheadings are listed below.

Thoughts

In addition to those abnormalities looked at under ‘speech’ (see above), abnormalities of thought content and thought possession are discussed here. Delusions (Table 23.2) can be further categorized as primary or secondary. Depending on whether they arise de novo or in the context of other abnormalities in mental state.

Cognitive state

Testing can be divided into tests of diffuse and focal brain functions.

Diffuse functions

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Risk

Risk can be broken down into two parts: the risk that the patient poses to themselves and that which they pose to others (Table 23.3). You will have already made an appraisal of risk in your initial preparations for seeing the patient (Box 23.2) and in checking ‘forensic history’ (Table 23.1). It may be necessary to obtain additional information from family, friends or professionals who know the patient – this may save time and prove invaluable.

Table 23.3 The assessment of risk

| Risk to self | Risk to others | |

|---|---|---|

Active | Acts of self-harm or suicide attempts | Aggression towards others – this may be actual violence or threatening behaviour |

Look for prior history of self-harm and what may have precipitated or prevented it | A past history of aggression is a good predictor of its recurrence. Look at the severity and quality of and remorse for prior violent acts as well as identifiable precipitants that might be avoided in the future (e.g. alcohol) | |

Passive | Self-neglect | Neglect of others – always find out whether children or other dependants are at home |

Manipulation by others |

Severe behavioural disturbance

Patients who are aggressive or violent cause understandable apprehension in all staff, and are most commonly seen in the accident and emergency department. Information from anyone accompanying the patient, including police or carers, can help considerably. Box 23.3 gives the main causes of disturbed behaviour.

Defence mechanisms

Although not strictly part of the mental state examination, it is useful to be able to identify psychological defences in ourselves and our patients. Defence mechanisms are mental processes that are usually unconscious. Some of the most commonly used defence mechanisms are described in Table 23.4 and are useful in understanding many aspects of behaviour.

Table 23.4 Common defence mechanisms

| Defence mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

Repression | Exclusion from awareness of memories, emotions and/or impulses that would cause anxiety or distress if allowed to enter consciousness |

Denial | Similar to repression and occurs when patients behave as though unaware of something that they might be expected to know, e.g. a patient who, despite being told that a close relative has died, continues to behave as though the relative were still alive |

Displacement | Transferring of emotion from a situation or object with which it is properly associated to another that gives less distress |

Identification | Unconscious process of taking on some of the characteristics or behaviours of another person, often to reduce the pain of separation or loss |

Projection | Attribution to another person of thoughts or feelings that are in fact one’s own |

Regression | Adoption of primitive patterns of behaviour appropriate to an earlier stage of development. It can be seen in ill people who become child-like and highly dependent |

Sublimation | Unconscious diversion of unacceptable behaviours into acceptable ones |

Classification of psychiatric disorders

Psychiatric classifications have traditionally divided up disorders into neuroses and psychoses.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders published by the World Health Organization has largely abandoned the traditional division between neurosis and psychosis, although the terms are still used. The disorders are now arranged in groups according to major common themes (e.g. mood disorders and delusional disorders). A classification of psychiatric disorders derived from ICD-10 is shown in Table 23.5, and this is the classification mainly used in this chapter (ICD-11 will be available in 2014).

Table 23.5 International classification of psychiatric disorders (ICD-10)

FURTHER READING

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. Text Revision (DSM-5). Washington, DC: APA; 2013.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Causes of a psychiatric disorder

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Psychiatric aspects of physical disease

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Table 23.6 Psychiatric conditions sometimes caused by physical diseases

| Psychiatric disorders/symptom | Physical disease |

|---|---|

Depressive illness | Hypothyroidism |

Cushing’s syndrome | |

Steroid treatment | |

Brain tumour | |

Anxiety disorder | Thyrotoxicosis |

Hypoglycaemia (transient) | |

Phaeochromocytoma | |

Complex partial seizures (transient) | |

Alcohol withdrawal | |

Irritability | Post-concussion syndrome |

Frontal lobe syndrome | |

Hypoglycaemia (transient) | |

Memory problem | Brain tumour |

Hypothyroidism | |

Altered behaviour | Acute drug intoxication |

Postictal state | |

Acute delirium | |

Dementia | |

Brain tumour |

Factors that increase the risk of a psychiatric disorder in someone with a physical disease are shown in Table 23.7.

Table 23.7 Factors increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders in the general hospital

Patient factors |

Setting |

Physical conditions |

Treatment |

Differences in treatment

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

Functional or psychosomatic disorders

So-called functional (in contrast to ‘organic’) disorders are illnesses in which there is no obvious pathology or anatomical change in an organ and there is a presumed dysfunction of an organ or system. Examples are given in Table 23.8. The psychiatric classification of these disorders would be somatoform disorders, but they do not fit easily within either medical or psychiatric classification systems, since they occupy the borderland between them. This classification also implies a dualistic ‘mind or body’ dichotomy, which is not supported by neuroscience. Since current classifications still support this outmoded understanding, this chapter will address these conditions in this way.

Table 23.8 ‘Functional’ somatic syndromes

Because epidemiological studies suggest that having one of these syndromes significantly increases the risk of having another, some doctors believe that these syndromes represent different manifestations of a single ‘functional syndrome’, indicating a global somatization process. Functional disorders also have a significant association with depressive and anxiety disorders. Against this view is the evidence that the majority of primary care people with most of these disorders do not have either a mood or other functional disorder. It also seems that it requires a major stress or the development of a co-morbid psychiatric disorder in order for such sufferers to see their doctor, which might explain why doctors are so impressed with the associations with both stress and psychiatric disorders. Doctors have historically tended to diagnose ‘stress’ or ‘psychosomatic disorders’ in people with symptoms that they cannot explain. History is full of such disorders being reclassified as research clarifies the pathology. An example is writer’s cramp (p. 1122) which most neurologists now agree is a dystonia rather than a neurosis.

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)

Clinical features

Aetiology

Functional disorders often have some aetiological factors in common with each other (Table 23.9), as well as more specific aetiologies. For instance, CFS can be triggered by certain infections, such as infectious mononucleosis and viral hepatitis. About 10% of patients who have infectious mononucleosis have CFS 6 months after the onset of infection, yet there is no evidence of persistent infection in these patients. Those fatigue states which clearly do follow on a viral infection can also be classified as post-viral fatigue syndromes.

Table 23.9 Aetiological factors commonly seen in ‘functional’ disorders

Management

The general principles of the management of functional disorders are given in Box 23.4. Specific management of CFS should include a mutually agreed and supervised programme of gradually increasing activity. However, only a quarter of patients recover after treatment. It is sometimes difficult to persuade a patient to accept what are inappropriately perceived as ‘psychological therapies’ for such a physically manifested condition. Antidepressants do not work in the absence of a mood disorder or insomnia.