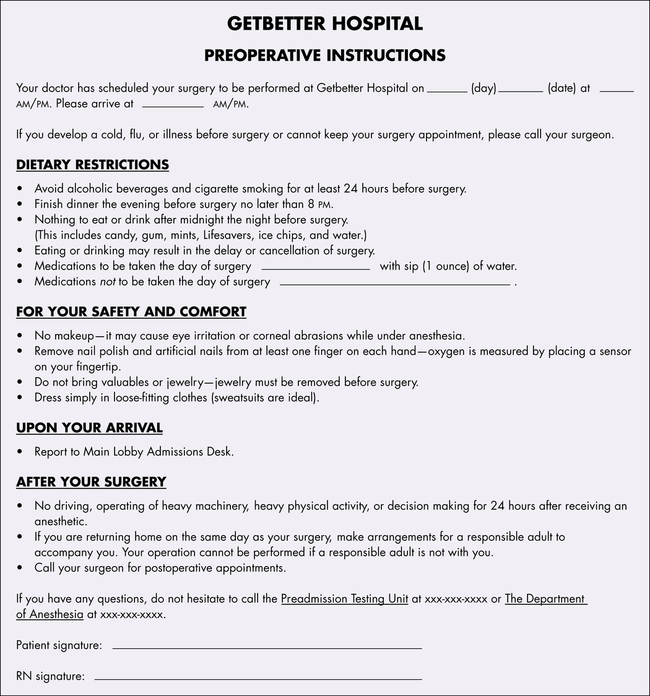

Chapter 21 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Discuss the importance of preoperative preparation. • Describe the content of preoperative patient teaching. • List several preoperative assessment factors relevant to all presurgical patients. • Identify the key elements in a successful presurgical interview. Regardless of the physical setting in which an invasive or surgical procedure will be performed, each patient should be adequately assessed and prepared so that the effects and potential risks of the surgical intervention are minimized. This involves both physical and emotional preparation. Perioperative caregivers should establish a baseline for the patient’s preoperative condition so that changes that occur during the perioperative/perianesthesia care period can be easily recognized. Some of the preoperative preparations can be performed in the surgeon’s office. Patients are then referred to the preoperative testing center of the hospital or ambulatory care facility. Tests and records should be completed and available before the patient is admitted the day of the surgical procedure. Preadmission tests (PATs) are scheduled according to the guidelines of each facility. Some tests are acceptable only for a 30-day period or are repeated before admission. The type of testing performed depends on the patient’s known or suspected condition and the complexity of the surgical procedure.1 The preoperative preparations include the following: 1. Medical history and physical examination. These are performed and documented by a physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant (PA), or the registered nurse first assistant (RNFA). Allergies and sensitivities should be noted.7 The preoperative nurse establishes the baseline for the patient’s vital signs (Fig. 21-1). 2. Laboratory tests. Testing should be based on specific clinical indicators or risk factors that could affect surgical management or anesthesia.1 Tests include age, sex, preexisting disease, magnitude of surgical procedure, and type of anesthesia. Ideally these tests should be completed 24 hours before admission so the results are available for review. Some facilities perform laboratory studies the morning of the procedure.8 a. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and blood glucose may be routinely tested for patients ages 60 years or older. b. Hematocrit is usually ordered for women of all ages before the administration of a general anesthetic. c. Complete blood count and blood chemistry profile may be indicated. Differential, platelet count, activated partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time also may be ordered. d. Urinalysis may be indicated by the type of surgical procedure, medical history, and/or physical examination. 3. Blood type and crossmatch. If a transfusion is anticipated, the patient’s blood is typed and crossmatched. Many patients prefer to have their own blood drawn and stored for autotransfusion.8 Patients should be advised that blood banks charge an additional fee to store and preserve blood for personal use. Even if the patient is to have an autotransfusion, his or her blood should still be typed and crossmatched in the event that additional transfusions are needed. If the patient refuses to accept blood transfusions, the appropriate documentation of refusal should be completed according to the policies and procedures of the facility. 4. Chest x-ray. A preoperative chest x-ray study is not routinely required for all patients. It may be required by facility policy or medically indicated as an adjunct to the clinical evaluation of patients with cardiac or pulmonary disease and for smokers, patients age 60 years or older, and cancer patients.12 5. Electrocardiogram (ECG). If the patient has known or suspected cardiac disease, an ECG is mandatory. Depending on the policy of the facility, an ECG may be routine for patients ages 40 years or older. 6. Diagnostic procedures. Special diagnostic procedures are performed when specifically indicated (e.g., Doppler studies for vascular surgery).9,10 7. Written instructions. The patient should receive written preoperative instructions to follow before admission for the surgical procedure. These instructions should be reviewed with the patient in the surgeon’s office or in the preoperative testing center (Fig. 21-2). a. To prevent regurgitation or emesis and aspiration of gastric contents, the patient should not ingest solid foods before the surgical procedure. These instructions are usually stated as NPO after midnight. (NPO is the Latin abbreviation for nil per os, or nothing by mouth.) Solid foods empty from the stomach after changing to a liquid state, which may take up to 12 hours. Clear fluids may be unrestricted until 2 to 3 hours before the surgical procedure, but only at the discretion of the surgeon or anesthesia provider in selected patients. NPO time usually is reduced for infants, small children, patients with diabetes, and older adults prone to dehydration. b. The physician may want the patient to take any essential oral medications that he or she normally takes. These can be taken as prescribed with a minimal fluid intake (a few sips of water) up to 1 hour before the surgical procedure. c. The skin should be cleansed to prepare the surgical site. Many surgeons want patients to clean the surgical area with an antimicrobial soap preoperatively or have the patient shower with an antimicrobial sponge, commonly chlorhexidine, the morning of surgery.2 Patients should be told not to allow the soap to get in the eyes. Chlorhexidine preparations can harm the corneas and tympanic membranes. Patients who will undergo a surgical procedure on the face, ear, or neck are advised to shampoo their hair before admission, because this may not be permitted for a few days or weeks after the procedure. d. Nail polish and acrylic nails should be removed to permit observation of and access to the nailbed during the surgical procedure. The patient should be advised to uncover at least one fingernail if the anesthesia provider will use these monitoring devices during the procedure. Either the finger or toe can be used when a digit is desired, but the finger is usually more accessible. Some sensors are adhesive and can be placed on an earlobe or across the bridge of the nose. The nailbed is a vascular area, and the color of the nailbed is one indicator of peripheral oxygenation and circulation. The Oxisensor (optode) of a pulse oximeter may be attached to the nailbed to monitor oxygen saturation and pulse rate. A finger cuff may be used for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Nail polish or acrylic nails inhibit contact between these devices and the vascular bed. e. Jewelry and valuables should be left at home to ensure safekeeping. If electrosurgery will be used, patients should be informed that all metal jewelry, including wedding bands and religious artifacts, should be removed to prevent possible burns. Loss prevention is a consideration as well. f. Patients should be given other special instructions about what is expected, such as when to arrive at the surgical facility. A responsible adult should be available to take the patient home if the procedure, medication, or anesthetic agent renders the patient incapable of driving. Family members or significant others should know where to wait and where the patient will be taken after the surgical procedure. 8. Informed consent. The physician should obtain informed consent from the patient or legal designee. After explaining the surgical procedure and its risks, benefits, and alternatives, the surgeon should document the process and have the patient sign the consent form. This documentation becomes part of the permanent record and accompanies the patient to the OR. Policy and state laws dictate the parameters for ascertaining an informed consent. 9. Nurse interview. A perioperative/perianesthesia nurse should meet with the patient to make a preoperative assessment.11 Ideally an appointment with the perioperative nurse is arranged when the patient comes to the facility for preoperative tests. Through physiologic and psychosocial assessments, the nurse collects data for the nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes, and plan of care. From the assessment data and nursing diagnoses, the nurse establishes expected outcomes with the patient. The nurse develops the plan of care, which becomes a part of the patient’s record. The nurse reviews the written preoperative instructions and consent form with the patient to assess the patient’s knowledge and understanding. The nurse also provides emotional support and teaches the patient in preparation for postoperative recovery. Before or after the interview, the patient may view a videotape to reinforce information. 10. Anesthesia assessment. An anesthesia history and physical assessment are performed before a general or regional anesthetic is administered.11 The history may be obtained by the surgeon, and/or the patient may be asked to complete a questionnaire for the anesthesia provider in the surgeon’s office or in the preoperative testing center. An interview by an anesthesia provider or nurse anesthetist may be conducted before admission if the patient has a complex medical history, is high risk, or has a high degree of anxiety. All patients should understand the risks of and alternatives to the type of anesthetic to be administered. After discussion with the anesthesia provider, the patient should sign an anesthesia consent form. 1. Bowel preparation. “Enemas till clear” may be ordered when it is advantageous to have the bowel and rectum empty (e.g., gastrointestinal procedures such as bowel resection or endoscopy, and surgical procedures in the pelvic, perineal, or perianal areas). An intestinal lavage with an oral solution that induces diarrhea may be ordered to clear the intestine of feces. Solutions such as GoLYTELY or Colyte normally will clear the bowel in 4 to 6 hours. Because potassium is lost during diarrhea, serum potassium levels should be checked before the surgical procedure.4,5,8,9 Geriatric, underweight, and malnourished patients are prone to other electrolyte disturbances from intestinal lavage. The broadened scope of perioperative nursing encompasses the phases of preoperative and postoperative care that contribute to the continuity of patient care. Preoperative visits to patients are made by RNFAs or perioperative/perianesthesia nurses skilled in interviewing and assessment. These interviews afford nurses an opportunity to learn about the patients, establish rapport, and develop a plan of care before the patients are brought to the perioperative environment.3,11 The advantages of preoperative visits with patients include the following: 1. An experienced perioperative/perianesthesia nurse is well qualified to discuss a patient’s OR experience. The nurse can orient and prepare the patient and family for the procedure and for the postoperative period. 2. The perioperative/perianesthesia nurse can review critical data before the procedure and assess the patient before planning care. The surgical site is marked by the surgeon or surgeon’s designee. 3. Visits improve and individualize intraoperative care and efficiency and prevent needless delays in the OR. 4. Visits foster a meaningful nurse-patient relationship. Some patients are reluctant to reveal their feelings and needs to someone in a short-term relationship. 5. Visits make intraoperative observations more meaningful by establishing a baseline for the measurement of patient outcomes. 6. Visits contribute to patient cooperation and involvement by facilitating communication. Mutual goals and expected outcomes are more easily developed. 7. Visits enhance the positive self-image of the perioperative nurse and contribute to job satisfaction, which in turn reduce job turnover and are thus benefits to the hospital. Because of increased patient contact, visits make perioperative and perianesthesia nursing more attractive to those who enjoy patient proximity and teaching. The disadvantages associated with preoperative visits include: 1. Cost-containment measures may not provide adequate staffing or allow time to visit patients. 2. The admission of patients on the day of the surgical procedure or late the day before the procedure makes the timing of visits difficult. 3. Visits may produce friction among different team factions if the program is not well planned and executed. 4. Repetitious use of interviewing terminology may lead to a lack of enthusiasm and spontaneity on the part of nurse interviewers. 5. If the nurse’s interviewing skills are not practiced, patients may feel their privacy is being invaded. 6. Barriers to visits may arise from the nurse’s inability to do the following: a. Verbalize and communicate effectively. b. Handle or accept a patient’s illness. c. Handle emotionally stressed persons. d. Understand cultural, ethnic, and value system differences. e. Function efficiently outside of his or her customary environment. f. Recognize how personal beliefs and biases can influence objectivity. Determine the level of patient understanding about the surgical procedure. One method is to ask, “Can you tell me what we will be doing for you during your surgical procedure?” Some patients will not be able to articulate the terms or adequately describe the procedure.3 Direct inquiry about specific procedures may be necessary, but give the patient plenty of opportunities to describe the anticipated procedure in his or her own words. 1. Review the patient’s chart and records. Focus on medical and nursing diagnoses and the surgical procedure to be performed. Collect any information relevant to planning care in the OR. If the patient is admitted to the hospital, discuss the assessment data and the plan of care with the unit nurses before visiting the patient. Nursing data include the following pertinent information; these baseline parameters are essential for accurate intraoperative and postoperative assessment. a. Biographic information (name, age, sex, family status, ethnic background, educational level, patterns of living, previous hospitalization and surgical procedures, religion). b. Physical findings (vital signs; height; weight; skin integrity; allergies; the presence of pain, drainage, or bleeding; state of consciousness and orientation; sensory or physical deficits; assistive aids or prosthetics). c. Special therapy (tracheostomy, inhalation therapy, hyperalimentation). d. Emotional status (understanding, expectations, specific problems concerning comfort, safety, language barrier, and other concerns). 2. Choose an optimal time and place without interruptions. a. Patients who will be admitted on the day of the surgical procedure may be interviewed in the preoperative testing center several days before the surgical procedure. If this is not feasible, a telephone call to the patient may provide an alternative means of contact. b. Patients who have been admitted to the hospital may be visited on a patient care unit the day before the surgical procedure. The best time to visit a patient is early evening—after dinner and before visiting hours. c. Allow adequate time for the interview, usually 10 to 20 minutes unless the patient has complex problems or special needs that require more time. Give the patient time to think and respond and to ask questions. d. If the patient is in acute physical or psychological distress, offer support and consider rescheduling the visit. The visit may need to be canceled or conducted through a family member or significant other. An emergency surgical patient may be assessed in the preoperative holding area. e. Do not conduct the interview on the morning of the procedure unless there is no other choice. Patients are not psychologically receptive to preoperative teaching at this time. Premedicated patients may be susceptible to suggestions such as “You will have minimal discomfort after the surgical procedure.” 3. Greet the patient by introducing yourself and explaining the purpose of the visit. Tell the patient that the visit is a routine part of care so the patient does not feel singled out because of his or her medical diagnosis. Unless specifically requested to use a first name, demonstrate respect at all times by addressing the patient by his or her last name, preceded by Mr., Mrs., or Ms. Terms such as honey, dear, or sweetheart are unacceptable. Children are usually addressed by their given first name unless the family uses a nickname.3 a. Put the patient at ease. Sit close so the patient can easily see and hear you. b. Secure the patient’s attention and cooperation. Establish eye contact. c. Speak first with the patient alone (unless the patient is a small child, an individual who needs an interpreter, or an individual who is mentally impaired). This affords the patient privacy so he or she may feel free to talk. Then, if the patient is willing, the family may be invited to participate and ask questions. The family should be present during the preoperative teaching to learn how to assist the patient postoperatively. d. Allow the patient to maintain self-respect and dignity. e. Instill confidence in the patient by having a neat appearance and a positive attitude. Establish rapport by demonstrating warmth and genuine interest. Avoid displaying an authoritative manner. f. Use language at the patient’s level of development, understanding, and education. 4. Obtain information by asking about the patient’s understanding of the surgical procedure. Disfiguring or palliative procedures can be stressful to the patient. Psychological counseling may be indicated.6 a. Assess the patient’s level of information and understanding and check its accuracy to determine whether further instruction or clarification is needed. Ask questions such as, “What has your surgeon told you about the surgical procedure?” Correct any misconceptions about the surgical procedure as appropriate within the scope of nursing. b. Permit the patient to talk openly. The objective is to gather data that will generate the plan of care to be implemented by the perioperative team. c. Direct questions should be used with caution and are not suitable for collecting all objective data. Construct open-ended questions to elicit information more detailed than one-word answers. d. Listen attentively. To preserve self-esteem, the patient may tell you what he or she thinks you want to hear. A patient’s statement that ends in a question may be either a request for more information or an expression of a feeling or attitude. 5. Orient the patient to the environment of the OR suite, and interpret policies and routines. a. Tell the patient the scheduled time of the surgical procedure, the approximate length of the procedure, and the probable length of stay in the PACU. Explain the procedures that will be performed in the preoperative holding area before the surgery if this is the routine. b. Ask the patient if family members or friends will be at the facility during the surgical procedure. They should be informed how early to be there to see the patient before sedation is given. Tell the patient and family where the waiting room is located. c. Tell the patient that the family will be updated on the progress of the surgical procedure and informed when he or she arrives in the PACU if this is hospital policy. Communicating the progress of the procedure, especially if it is prolonged, provides emotional support, and decreases the family’s anxiety. 6. Review the preoperative preparations that the patient will experience. a. Familiarize the patient with whom and what will be seen in the perioperative environment. Many perioperative nurses wear OR attire and laboratory coats with name tags when they visit patients, which familiarizes patients with the way they will see personnel the next day. Attire should be changed if the nurse reenters the OR suite after the visit. b. Use discretion regarding how much the patient should know and wants to know. Use words that do not evoke an anxiety-inducing state of mind. Do not use words with unpleasant associations, such as knife, needle, or nausea. c. Postoperative recovery begins with preoperative teaching, but keep the explanations short and simple. Excessive detail can increase patient anxiety, which reduces the attention span. d. Give practical information about what the patient should expect, such as withholding fluids, drowsiness, and/or dry mouth caused by preoperative medications; transportation to the OR and the holding area; and where he or she will be taken after the surgical procedure. Instruct the patient not to hesitate to ask for assistance at any time. Explain any other relevant special precautions. e. Give the basic reasons for procedures and regulations; this reduces patient anxiety. With children and older adults, the nurse may have to repeat information as reinforcement. f. Explain only the procedures of which the patient will be aware. g. If patient will be going to the ICU after the procedure, tell the family what they will see there, such as monitors and machines.

Preoperative preparation of the patient

Hospitalized patient

Preoperative preparation of all patients

Preadmission procedures

Evening before an elective surgical procedure

Preoperative visit by the perioperative/perianesthesia nurse

Pros of preoperative visits.

Cons of preoperative visits.

Interviewing skills.

Structured preoperative visits

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Website

Website