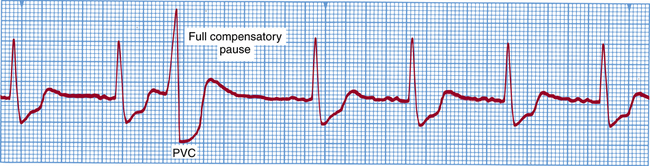

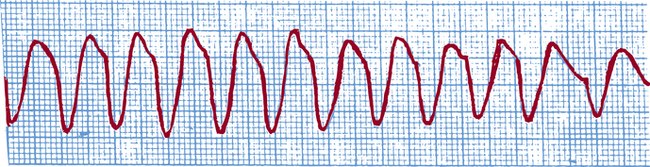

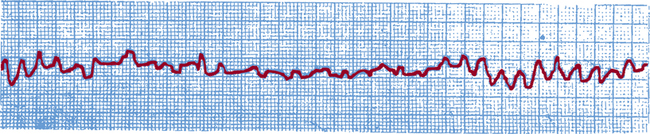

Chapter 31 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe several respiratory complications that are possible in the perioperative period. • Identify three potential dysrhythmias that may complicate the patient’s perioperative course. • Demonstrate the procedure for weighing surgical sponges in the operating room. • List the primary drugs used in the management of an acute malignant hyperthermic crisis. • Identify three methods for preventing hypothermia in the perioperative patient. • Types of preoperative medications • Type and duration of anesthesia • Type and duration of assisted ventilation • Position of the patient during the surgical procedure Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a major cause of death during a surgical procedure and in the immediate postoperative period. Some intraoperative problems may extend into postoperative recovery.8 PE is an obstruction of the pulmonary artery or one of its branches by an embolus, most often a blood clot, but can be fat or other material. The most common cause of PE is stasis of blood, particularly in the low-pressure regions such as deep veins of the legs and pelvis, where the majority of thrombi arise.8 These clots become detached and are carried to the lungs. Nonspecific symptoms depend on whether the embolism is mild or massive. The patient may have dyspnea, pleural pain, hemoptysis, tachypnea, crackles, tachycardia, mild fever, or persistent cough. Patients with massive emboli have air hunger, hypotension, shock, and central cyanosis.11 Treatment of pulmonary emboli consists of bed rest, oxygen therapy, anticoagulant therapy, thrombolytic agents, and sometimes a surgical procedure to remove the emboli or place a vena cava filter to prevent additional clots from reaching the lungs. Other causes of hypotension include the following: • Volume depletion and/or hemorrhage • Circulatory abnormalities (e.g., cardiac tamponade, heart failure) • Cerebral or pulmonary embolism (fat embolism from fracture sites, amniotic fluid emboli during delivery, or air emboli from introduction of air into the circulation during an infusion or procedure) • Myocardial ischemia or infarction • Changes in position, especially if executed rapidly or roughly • Excessive preanesthetic medication (postural hypotension may follow narcotic administration) • Epidural or spinal anesthesia above the level of T6 (sympathetic block) • Potent therapeutic drugs (e.g., tranquilizers, adrenal steroids, antihypertensives) given before the anesthetic An ectopic focus in the ventricles stimulates the heart to contract or beat prematurely before the regularly scheduled sinoatrial impulse arrives (Fig. 31-1). Primary precipitating factors are electrolyte or acid-base imbalance, myocardial infarction, digitalis toxicity, and caffeine. The premature ventricular contraction (PVC) must be distinguished from a premature atrial contraction (PAC). Isolated PVCs may not require treatment, but those occurring in clusters of two or more or more than five or six per minute require therapy. The aim is to quiet the irritable myocardium and restore adequate cardiac output. A rapid heart rate (100 to 220 beats per minute) may be caused by ventricular ischemia or irritability, anoxia, or digitalis intoxication. The heart rate does not allow time for ventricular filling (Fig. 31-2). The resultant reduced cardiac output predisposes the patient to ventricular fibrillation or cardiac failure. Ventricular tachycardia is treated by prompt IV administration of lidocaine or procainamide, or intramuscular quinidine. The most serious of all dysrhythmias, fibrillation is characterized by total disorganization of ventricular activity (Fig. 31-3). There are rapid and irregular, uncoordinated, random contractions of small myocardial groups without effective ventricular contraction or cardiac output. Circulation ceases. The patient in fibrillation is unconscious and possibly convulsing from cerebral hypoxia. 1. Precordial thump: In a monitored patient a fast, sharp, single blow to the midportion of the sternum (using the nipple line as a landmark) may be delivered with the bottom fleshy part of a closed fist struck from 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 cm) above the chest. The blow generates a small electrical stimulus in a heart that is reactive. It may be effective in restoring a beat in cases of asystole or recent onset of dysrhythmia. 2. Asynchronous cardioversion: Prompt defibrillation by short-duration electric shock to the heart produces simultaneous depolarization of all muscle fiber bundles, after which spontaneous beating (conversion to spontaneous normal sinus rhythm) may resume if the myocardium is oxygenated and not acidotic. Defibrillation of an anoxic myocardium is difficult. The time that fibrillation is started should be noted. The electric shock is coordinated with controlled ventilation and cardiac compression. CPR begins as soon as fibrillation is identified. Many variables may affect defibrillation, such as body weight, paddle position, electrical waveform, and resistance to electric current flow. Procedures follow an established protocol. 3. Adjunct drug therapy: Drugs are given as necessary: vasopressor, cardiotonic, and myocardial stimulant drugs to maintain a useful heartbeat; vasodilator or antidysrhythmic drugs to prevent recurrence; and sodium bicarbonate to combat acidosis. Continuous monitoring of the heart and laboratory analysis of arterial blood gases is essential. 1. Standard position: One electrode is placed just to the right of the upper sternum below the clavicle. The other is positioned to the left of the cardiac apex (i.e., left of the nipple at the fifth intercostal space along the left midaxillary line). The delivered current flows through the long axis of the heart. 2. Anterior-posterior position: One electrode is placed anteriorly over the precordium between the left nipple and the sternum. The other is positioned posteriorly behind the heart immediately below the left scapula, avoiding the spinal column. This allows for more energy passage through the heart, but placement is more difficult. 1. Monitoring of the heart rhythm and rate: The ability to recognize the rhythms that precede arrest permits intervention that may prevent arrest. If the cardiac status is not under constant monitoring, hypoxia and acidosis may be present and require correction before other therapeutic modalities can be used effectively. 2. Establishment of an IV lifeline: Venous cannulation provides access to peripheral and central venous circulation for administering drugs and fluids, obtaining venous blood specimens for laboratory analysis, and inserting catheters into the right side of the heart and pulmonary arteries for physiologic monitoring and electrical pacing. If cardiac arrest appears imminent or has occurred, cannulation of a peripheral or femoral vein should be attempted first so as not to interrupt CPR. To keep the infusion open, the rate should be kept slow. The usual complications to all IV techniques should be guarded against. Some of the specific precipitating factors are dysrhythmias, emboli, extreme hypotension or hypovolemia, respiratory obstruction, aspiration, effects of drugs, anesthetic overdosage, excessively rapid or unsmooth induction, sepsis,6 pharyngeal stimulation, metabolic abnormalities (acidosis, toxemia, electrolyte imbalance), poor cardiac filling caused by positioning, manipulation of the heart, central nervous system trauma, anaphylaxis, and electric shock from ungrounded or faulty electrical equipment. • ECG and temperature monitoring • No stimulation during induction • Maintenance of an adequate airway • Oxygen and carbon dioxide monitoring • Arterial blood pressure monitoring • Appropriate positioning and slow position changes with the patient under anesthesia; no weight on the patient • Gentle handling of tissues with minimal traction and manipulation Sympathomimetics are used most often for the following purposes: • To increase force (inotropic effect), maintain contractility (noninotropic effect), or decrease the stroke volume of myocardial contractions • To increase or decrease arterial blood pressure • To increase renal blood flow • To stimulate the central nervous system • To prolong the effect of local anesthetics Patients receiving any of the following drugs must be carefully monitored.

Potential perioperative complications

Respiratory complications

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

Cardiovascular complications

Hypotension

Etiology

Ventricular dysrhythmias

Premature ventricular contraction

Ventricular tachycardia

Ventricular fibrillation

Treatment.

Defibrillation: equipment and technique.

Prevention.

Cardiac arrest

Etiology

Prevention

Intravenous cardiovascular drugs

Drugs by classification

Website

Website