, Arthur H. Cohen2, Robert B. Colvin3, J. Charles Jennette4 and Charles E. Alpers5

(1)

Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

(2)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

(3)

Department of Pathology Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(4)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

(5)

Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Abstract

Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis is a kidney disease that follows an infection. The most common and best-understood form of acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis is poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, but other infectious organisms may also be the cause of this disorder.

Introduction/Clinical Setting

Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis is a kidney disease that follows an infection. The most common and best-understood form of acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis is poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, but other infectious organisms may also be the cause of this disorder.

A large number of bacterial and mycotic infections may be followed by acute glomerulonephritis. Especially after persistent extrarenal bacterial infections such as bacterial endocarditis, deep abscesses, cellulitis, and infected atrioventricular shunts in hydrocephalus or some chronic viral infections including some cases of Hepatitis B or C, proliferative and inflammatory patterns of glomerulonephritis can occur and these broadly can be categorized as infection-related glomerulonephritis. Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis can be considered as a distinct subset within this group, characterized clinically by a preceding bacterial infection that is usually of streptococcal or staphylococcal type, a commonly self-limited course, and a typical constellation of pathologic findings. Most cases of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis are caused by group A streptococci and follow upper airway infections, such as pharyngitis or tonsillitis, by 14–21 days [1]. Especially in warmer climates acute glomerulonephritis also may follow skin infections. In recent decades the number of patients with poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis has decreased considerably in the United States and Europe. In developing countries the incidence of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis has remained high with an annual incidence that has been estimated to be in a range of 9.5–28.5 cases per 100,000 individuals [2–7]. In addition to the declining incidence, the number of biopsies demonstrative of acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis has decreased. In part this is due to the reluctance of clinicians to obtain a biopsy in a patient with classical or typical symptoms of acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis since the typical clinicopathologic features have become so well established, particularly in uncomplicated cases involving children, and because resolution of this disease commonly occurs within weeks of first presentation.

The disease occurs most commonly in children between the ages of 2 and 12 years and young adults and more often in males than in females [2, 3, 8, 9]. Recently it has been appreciated that adult diabetics and the elderly also have increased risk for this disorder [5]. Clinically the disease is characterized by an acute nephritic syndrome (acute glomerulonephritis). The symptoms include an abrupt onset of macroscopic hematuria, oliguria, acute renal failure manifested by a sudden decrease in the glomerular filtration rate, and fluid retention manifested by edema and hypertension [8]. Edema probably results from renal sodium retention caused by the sudden decrease in the glomerular filtration rate, rather than occurring as a consequence of hypoalbuminemia as in the nephrotic syndrome [8, 9]. Milder clinical presentations, such as asymptomatic microscopic hematuria, also can occur. Laboratory studies are directed at the urine sediment, which reveals red blood cells (which may be dysmorphic) with or without red blood cell casts, and with proteinuria; at measures of impaired renal function; and at measures that establish evidence of an immune response to streptococcal or viral antigens. In cases of streptococcal infection, elevated titers of antistreptolysin O antibodies or other streptococcal antigens (streptozyme assay) often suggest or confirm the diagnosis, but these can be falsely negative in a minority of affected patients [8]. In most cases, complement levels (either C3 or CH50 as a measure of the total complement activity) are low [5]. However, many cases demonstrate concomitantly normal C4 levels, suggesting that complement activation in these cases occurs primarily via the alternative pathway.

Pathologic Findings

The classic pathologic alterations in glomeruli include an exudative component (a term which refers to an influx of neutrophils) and hypercellularity (due to the influx of leukocytes—both neutrophils and monocytes—and concurrent proliferation of intrinsic renal cells), all of which is readily identifiable by light microscopy. In conjunction with the histologic findings, there are accumulations of discrete subepithelial immune deposits in glomerular capillary walls that have a highly specific ultrastructural appearance as “humps” [7, 10, 11]. In viral, parasitic, or treponemal infections, membranous or membranoproliferative patterns of glomerulonephritis are seen more often.

Light Microscopy

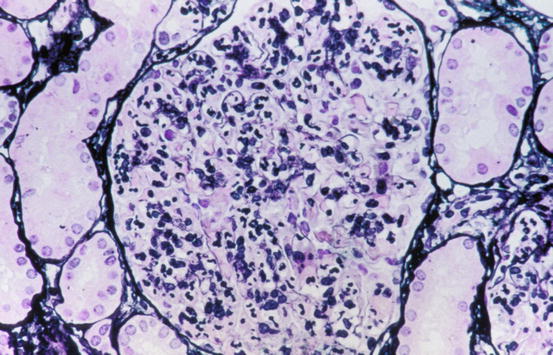

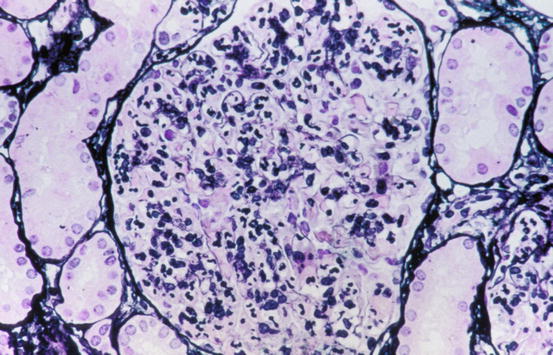

In acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis usually all glomeruli are affected (“diffuse”) and generally all to a similar extent. The glomerular capillaries are dilated and hypercellular, without necrosis. In many cases there is an increase of endothelial and/or mesangial cells, and the endothelial cells in particular appear swollen (a constellation of findings termed “endocapillary proliferation”). Glomerular capillaries typically demonstrate a prominent influx of inflammatory cells, especially neutrophils and monocytes (Fig. 5.1). Because of the large numbers of neutrophils, the descriptive term exudative glomerulonephritis has been applied to these lesions. Eosinophils and lymphocytes may be present, but they are usually scarce. The glomerular capillary walls are sometimes slightly thickened. In some biopsies, small nodules on the epithelial side of the glomerular capillary walls may be seen, when using high magnification in conjunction with trichrome or toluidine blue stains. These correspond to the subepithelial deposits (“humps”) that are seen by electron microscopy (see below). In severe cases, extracapillary proliferation with formation of crescents and/or adhesions (synechiae) can be seen. Erythrocytes and sometimes neutrophils may be present in Bowman’s space. In renal biopsies taken a few weeks after the appearance of clinical symptoms, the picture is often less inflammatory. The number of neutrophils will have decreased, the swelling of endothelial cells will have subsided, and the number of humps will have decreased. In this stage diffuse mesangial hypercellularity may still be seen, and this can remain for several months. Evidence of resolving or largely healed postinfectious glomerulonephritis may be overlooked or misdiagnosed as a mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis resulting from a noninfectious etiology [12]. This supports the contention that postinfectious glomerulonephritis occurs more frequently than is clinically appreciated [13].

Fig. 5.1

Diffusely hypercellular glomerulus in acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis with massive influx of neutrophils (Jones silver stain)

Tubular changes are less prominent than glomerular alterations. When proteinuria occurs, reabsorption droplets can be seen in the proximal tubular epithelial cells. Erythrocytes and sometimes neutrophils may be present in the lumen of some tubules. The extent of interstitial damage varies but is usually not extensive unless due to some other cause. Interstitial edema may be present, and mixed interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrates are common. Arteries and arterioles are usually unaffected.

Due to the combination of expansion of glomerular lobules, hypercellularity of the glomerular capillaries, and focal thickening of the capillary walls, postinfectious glomerulonephritis may be difficult to distinguish from membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis by light microscopy. Immunofluorescence and electron microscopy usually allow the distinction between the two diseases to be made. Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include lupus nephritis, which usually can be distinguished on clinical grounds and by the constellation of associated immunofluorescence and electron microscopic findings. Some cases of acute glomerulonephritis morphologically indistinguishable from postinfectious glomerulonephritis but with an atypical, non-resolving clinical course have proven to be cases of the recently recognized entity C3 glomerulopathy [14] or, in cases of recurrent hematuria, IgA nephropathy (see Chaps. 3 and 6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree