Portal Venous System

Portal Venous SystemSurgical Anatomy of the Portal Vein

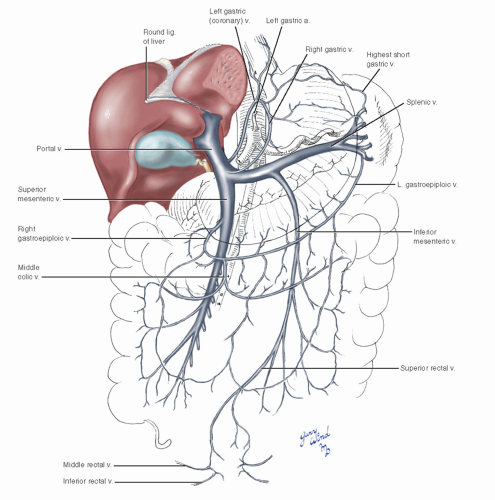

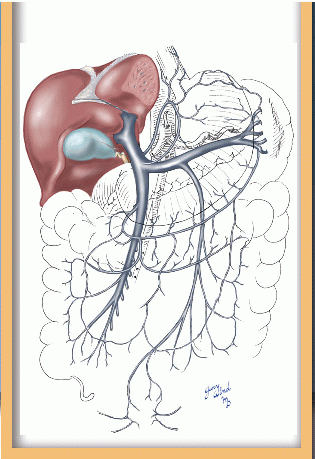

The portal venous system drains the viscera supplied by the celiac, superior, and inferior mesenteric arteries and normally carries the blood to the liver (Fig. 14-1). The portal vein is formed by the confluence of splenic and superior mesenteric veins at the level of the second lumbar vertebra. Most commonly, the inferior mesenteric vein joins the proximal splenic vein, but it may alternatively join the superior mesenteric vein or form a common junction with the other two veins. These three veins drain the areas supplied by their corresponding named arteries.

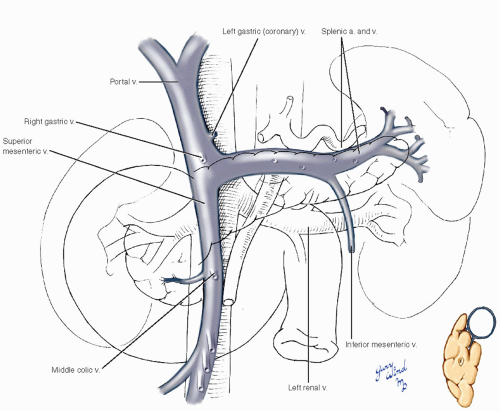

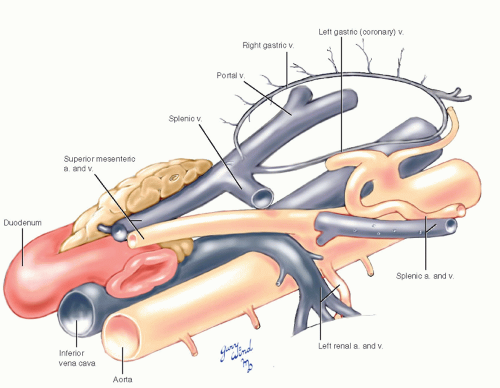

Anatomically, the superior mesenteric and splenic veins lie close to their corresponding arteries (Fig. 14-2). The superior mesenteric vein lies to the right of the artery in the root of the small bowel mesentery and ascends over the third portion of the duodenum and uncinate process of the pancreas. The vein passes behind the neck of the pancreas and is joined by the splenic vein near the cephalad border of the gland. The splenic vein is cradled in a groove running the length of the upper border of the posterior surface of the pancreas (inset). Numerous small branches drain from the tail and body of the pancreas into the apposed surface of the vein.

Fig. 14-2 The relationships of the main trunks of the portal system to the surrounding structures are shown. |

The inferior mesenteric vein lies deep to the left posterior parietal peritoneum and ascends in close proximity to the underlying infrarenal aorta.

It courses beneath the root of the transverse mesocolon and dives under the inferior border of the pancreas where it joins the splenic or superior mesenteric vein or their junction. From the confluence of these branches, the portal vein ascends within the thickened edge of the gastrohepatic ligament accompanied by the hepatic artery and common bile duct.

It courses beneath the root of the transverse mesocolon and dives under the inferior border of the pancreas where it joins the splenic or superior mesenteric vein or their junction. From the confluence of these branches, the portal vein ascends within the thickened edge of the gastrohepatic ligament accompanied by the hepatic artery and common bile duct.

Another component of the portal system is the circuit formed by the left (coronary) and right gastric veins that empty into the left side of the portal vein just proximal to the junction of splenic and superior mesenteric veins (Fig. 14-3). The right gastric vein lies along the lesser curvature of the stomach beneath the gastric root of the gastrohepatic omentum. The left gastric vein spans the distance between the esophagogastric junction and the posterior wall of the omental bursa lying alongside the left gastric artery. It descends diagonally over the celiac trunk beneath the posterior peritoneum of the omental bursa to reach the portal vein. The apex of this loop receives drainage from the lower esophageal veins. Small pyloric and duodenal veins also enter the portal vein near the gastric veins.

Fig. 14-3 The gastric vein circuit consists of the right gastric vein along the lesser curve of the stomach and the left gastric or coronary vein beneath the posterior peritoneum of the lesser sac. |

Secondary Portal Venous Connections

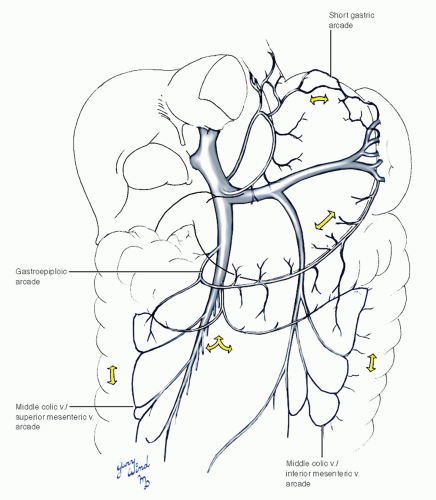

There are three more peripheral circuits through which major branches of the portal system communicate (Fig. 14-4). The gastroepiploic arch connects the terminal splenic vein with the superior mesenteric vein and runs in the gastrocolic omentum where it receives drainage from the omentum and greater curvature of the stomach. The second of these circuits is formed by connections between peripheral branches of the superior mesenteric, inferior mesenteric, and middle colic veins around the mesenteric margin of the colon. The final connection is between the short gastric branches of the terminal splenic vein and branches of the gastric circuit across the cardia of the stomach.

Portosystemic Venous Connections

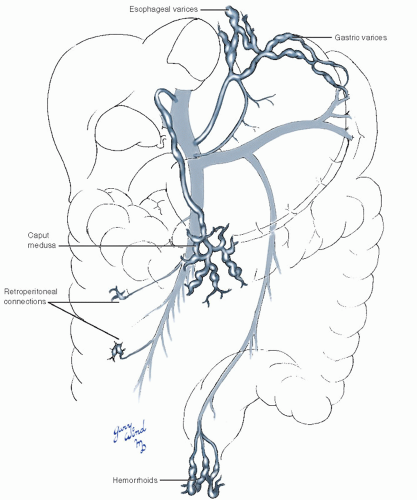

Portal hypertension occurs as a result of increased portal vein resistance or, on rare occasions, from increased portal vein flow. It is associated with a number of hepatic and extrahepatic disorders that have been well described elsewhere.1 Among other consequences of increased pressure in the portal system, the thin-walled veins become engorged. Normally small connections between the portal and systemic venous circulations often become clinically apparent.

There are several peripheral connections between the portal system and the systemic circulation that become enlarged as a result of abnormally elevated portal pressure (Fig. 14-5). Peripheral dilation is most dangerous in the submucosal esophageal plexus connecting the portal circulation to the azygous system. Resultant esophageal varicosities are in danger of erosion and massive hemorrhage.

Hemorrhoids are visible manifestations of the connection between superior rectal veins and middle and inferior rectal veins. Caput medusae results from engorgement of connections between the paraumbilical veins and veins of the anterior abdominal wall, connecting to the portal system via the recanalized umbilical vein in the edge of the falciform ligament. Multiple small retroperitoneal connections between the two systems (veins of Retzius) may lead to increased bleeding during retroperitoneal dissection and tissue mobilization.

Hemorrhoids are visible manifestations of the connection between superior rectal veins and middle and inferior rectal veins. Caput medusae results from engorgement of connections between the paraumbilical veins and veins of the anterior abdominal wall, connecting to the portal system via the recanalized umbilical vein in the edge of the falciform ligament. Multiple small retroperitoneal connections between the two systems (veins of Retzius) may lead to increased bleeding during retroperitoneal dissection and tissue mobilization.

Exposure of the Portal Circulation

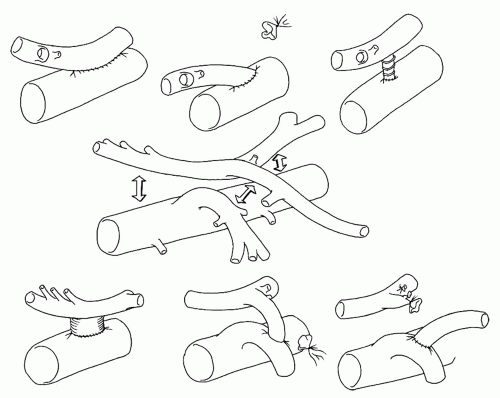

Historically, the main indication for exposure of the portal circulation was to create a portosystemic shunt for surgical decompression of portal hypertension. The management of patients with bleeding esophageal varices has evolved significantly in the past two decades, however. Liver transplant is now considered definitive therapy for portal hypertension, and there are numerous temporizing options that can achieve hemostasis and prevent rebleeding, including endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy or banding, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPs), and devascularization procedures.1,2,3 Operative shunts are rarely performed in the modern era, and may be contraindicated because they interfere with the anatomy in patients who may be eligible for liver transplant. However, some surgeons believe that surgical shunts represent a reasonable alternative in patients who are not candidates for liver transplant or who fail attempts at TIPs.1,3 A wide variety of surgical options is available for the treatment of patients who have had one or more variceal bleeds3 (Fig. 14-6). Surgical outcome is better when operations are performed

electively in patients with less advanced liver disease.

electively in patients with less advanced liver disease.

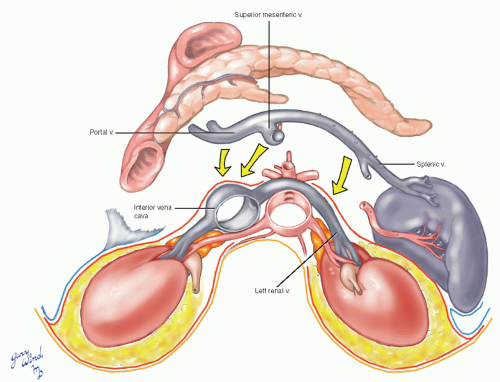

Therapeutic portal decompression shunts can generally be divided into two categories: nonselective and selective. Nonselective shunts include portacaval (both end-to-side and side-to-side), mesocaval, and proximal splenorenal anastomoses (Fig. 14-7). These shunts prevent recurrent bleeding if they remain patent but do not improve survival rates or quality of life because of the high associated rates of hepatic encephalopathy.1,3 Selective shunts include the Warren distal splenorenal shunt4

(Fig. 14-8) and variations of the nonselective shunts (e.g., Sarfeh small-diameter portacaval H graft5 and Johansen small-diameter portacaval anastomosis6).

(Fig. 14-8) and variations of the nonselective shunts (e.g., Sarfeh small-diameter portacaval H graft5 and Johansen small-diameter portacaval anastomosis6).

Beyond portal decompression surgery, there are two modern indications for exposure of the portal venous system: repair of traumatic injuries7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree