Patient Story

Max is a 65-year-old man who presents with a “terrible cough” and fever of several days’ duration. He has just returned from a business trip and is feeling quite run down. His cough is productive with rusty colored sputum. He is otherwise healthy and is a nonsmoker. His chest x-ray is similar to the one shown in Figure 53-1. He is diagnosed with probable bacterial pneumonia and is placed on antibiotics. You note that he has never had vaccinations against influenza or pneumococcus and you offer these to him at a follow-up visit when he is well.

Introduction

Pneumonia refers to an infection in the lower respiratory tract (distal airways, alveoli, and interstitium of the lung). Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has traditionally referred to pneumonia occurring outside of the hospital setting. More recently, a subgroup of CAP has been identified that is associated with healthcare risk factors (e.g., prior hospitalization, dialysis, nursing home residence, immunocompromised state); this form of pneumonia has been classified as a healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP), although definitions of HCAP vary. While severity and excess mortality are associated with HCAP, as well as a slight increase in multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogens, most studies do not support either a causal relationship between MDR and excess mortality or demonstrate benefit from broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage.1 It is likely that excess mortality is a result of underlying patient-related factors (e.g., older age, comorbidities, higher initial severity).1,2

Epidemiology

- Three to 4 million adults per year in United States are diagnosed with CAP (8 to 15 per 1000 persons/year).3,4

- Annual incidence rate of CAP requiring hospitalization: 267 per 100,000 population and 1012 per 100,000 individuals older than 65 years of age.5

- Ten percent to 20% of patients are admitted to the hospital.3,4,6 Of those, 10% to 20% are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).7

- Increased incidence in men and in blacks versus whites.3

- CAP is the most frequent cause of death caused by infectious disease in the United States and the eighth leading cause of death overall (2007).7,8

- Economic burden associated with CAP is estimated at more than $12 billion annually in the United States.7

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- In a study of children hospitalized with CAP (N = 254), the cause of the disease (identified in 85% of cases) was most often viral (62%, with 30% having evidence of both viral and bacterial pathogens).9 The most common pathogens were Streptococcus pneumoniae (37%), respiratory syncytial virus (29%), and rhinovirus (24%). Dual bacterial infections were found in 19 patients; only 1 patient of 125 tested had a positive blood culture.

- In a single U.S. hospital study, pathogens identified in adult patients with CAP separate from HCAP (N = 208) were S. pneumoniae (40.9%), Haemophilus influenzae (17.3%), Staphylococcus aureus (13.5%) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA, 12%).10 For HCAP, the most common pathogens were MRSA (30.6%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (25.5%). This distribution of pathogens for HCAP may be unique to this setting.

- Most common route of infection is microaspiration of oropharyngeal secretions colonized by pathogens. In this setting, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae are the most common pathogens.

- Pneumonia secondary to gross aspiration occurs postoperatively or in those with central nervous system disorders; anaerobes and Gram-negative bacilli are common pathogens.

- Hematogenous spread, most often from the urinary tract, results in Escherichia coli pneumonia, and hematogenous spread from intravenous catheters or in the setting of endocarditis may cause S. aureus pneumonia.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), fungi, Legionella, and many respiratory viruses are spread by aerosolization. Reported incidence rates of atypical pathogens vary greatly; for example, Legionella species were identified in patients with CAP in 1.3% (defined as positive urine antigen),10 1.4% (defined as 4-fold rise in antibody titer or a single titer of ≥400),11 and 18.9% (defined as 4-fold rise in antibody titer of 128),12 with coinfection with another pathogen in approximately 10%.

- Etiology is unknown in up to 70% of cases of CAP.

Risk Factors

- Age older than 70 years (relative risk [RR], 1.5 vs. 60- to 69-year-olds).

- Smoking more than 20 cigarettes/day (odds ratio [OR], 2.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 6.7)

- Alcohol consumption (RR, 9).

- Asthma (RR, 4.2), chronic bronchitis (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.13 to 4.37), and other chronic lung diseases or pulmonary edema.

- Previous respiratory infection (OR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.75 to 4.26).

- Uremia.

- Immune suppression (RR, 1.9).

- Malnutrition.

- Acid-suppressing drugs (proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonist; OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.46 and OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.36, respectively).14

Diagnosis

- Alcoholism—Consider S. pneumoniae, Klebsiella, S. aureus, and anaerobes.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—Consider S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and Moraxella.

- Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus—Consider S. pneumoniae and S. aureus.

- Sickle-cell disease—Consider S. pneumoniae.

- HIV with low CD4 count—Consider S. pneumoniae, Pneumocystis carinii, H. influenzae, Cryptococcus, and TB.

- Constellation of symptoms includes cough, fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain, and sputum production. Patients may also complain of fatigue, myalgia, and headache.4 Patients with viral or atypical pathogens (e.g., Mycoplasma, Chlamydia) often present with fever, nonproductive cough, and constitutional symptoms developing over several days; patients with Legionella pathogens may present initially with GI symptoms.4

- Signs include increased respiratory rate, dullness to percussion, bronchial breathing, egophony, crackles, wheezes, and pleural-friction rub. Lung findings in atypical pneumonia may be more diffuse.

- Sputum Gram stain may be helpful in determining etiology in hospitalized patients. Pretreatment Gram stain and culture of expectorated sputum should be performed only if a good-quality specimen is obtained; indications are the same as for blood cultures listed below.15 An adequate specimen has a more than 25 white blood cells (WBCs) and less than 10 epithelial cells per high-powered field. For intubated patients with severe CAP, an endotracheal aspirate sample should be obtained.15

- Testing of induced sputum has established merit primarily for detection of TB and P. carinii. SOR A Special stains are needed for detecting TB, P. carinii, and fungi.

- Blood cultures are not recommended routinely for nontoxic, fully immunized children with CAP managed in the outpatient setting.16 SOR B Blood cultures should be obtained in children who fail to demonstrate clinical improvement, and in those who have progressive symptoms or clinical deterioration after initiation of antibiotics.16 SOR B

- Blood cultures are recommended for children requiring hospitalization for presumed bacterial CAP that is moderate to severe, particularly those with complicated pneumonia.16 SOR C

- Routine diagnostic tests to identify an etiologic agent are optional for adult outpatients with CAP.15 SOR C Blood cultures should be considered in ambulatory patients with a temperature higher than 38.5°C (101.3°F) or lower than 36°C (96.8°F) and in those who are homeless or abusing alcohol.3 SOR C

- Blood cultures (2 sets prior to administration of antibiotics) are suggested for hospitalized patients who meet clinical indications (i.e., cavitary infiltrates, leukopenia, active alcohol abuse, chronic severe liver disease, asplenia, positive pneumococcal urinary antigen, or pleural effusion) or are admitted to the ICU.15 SOR A Blood cultures are positive in 6% to 20% of hospitalized patients.3 Investigators in a Canadian study found that blood cultures had limited usefulness in the routine management of patients admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated CAP; only 1.97% (15 of 760 patients) had a change of therapy directed by blood culture results.17

- Sensitive and specific tests for the rapid diagnosis of influenza virus and other respiratory viruses should be used in the evaluation of children with CAP.16 A positive influenza test may decrease both the need for additional diagnostic studies and antibiotic use, while guiding appropriate use of antiviral agents in both outpatient and inpatient settings.16 SOR A Serology (4-fold rise in immunoglobulin [Ig] M titer) may also be useful in diagnosing Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and other viral pneumonia.15 SOR C

- Urinary antigens may be useful in diagnosing Legionnaires disease (L. pneumophila) and S. pneumoniae, and are recommended in patients with severe CAP.15 SOR B Urinary antigen detection tests are not recommended for the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia in children as false-positive tests are common.16

- Procalcitonin, a peptide precursor of calcitonin used as a biomarker of bacterial infection and sepsis, has been used in the emergency room setting to distinguish between pneumonia (increased level) and an exacerbation of asthma 18 In one study, use of guidelines including measurement of procalcitonin versus standard guidelines in patients with lower respiratory infection reduced exposure to antibiotics (mean duration: 5.7 vs. 8.7 days).19

- Pulse oximetry should be performed in patients with pneumonia and suspected hypoxemia. The presence of hypoxemia should guide decisions regarding site of care and further diagnostic testing. SOR B

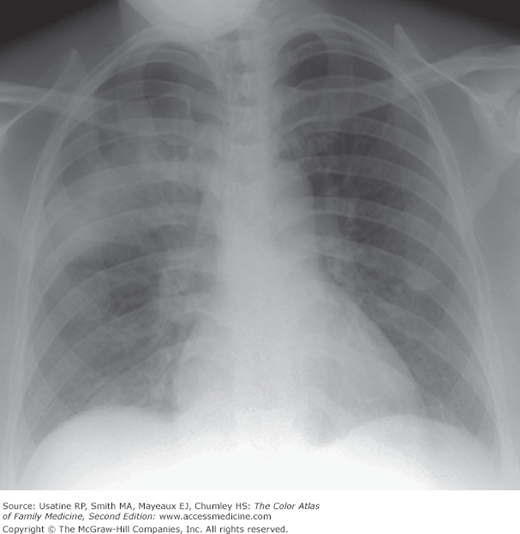

Routine chest x-ray (CXR) is not necessary for the confirmation of suspected CAP in children who are well enough to be treated in the outpatient setting (after evaluation in the office, clinic, or emergency department setting).16 SOR A CXR, posteroanterior and lateral, should be obtained in patients with suspected or documented hypoxemia, significant respiratory distress, those who failed initial antibiotic therapy, and hospitalized patients. SOR B

The diagnosis of pneumonia in adults based on clinical history and examination is only 47% to 69% sensitive and 58% to 75% specific, thus CXR is considered a standard part of evaluation.3,15 The presence of new infiltrate in conjunction with clinical features is diagnostic.6 If the initial CXR is negative in a patient with clinical features of pneumonia, the CXR should be repeated in 24 to 48 hours or a chest CT be considered. SOR C Ultrasound may be useful for evaluation of pleural effusion.20

There are 4 general patterns of pneumonia seen on CXR3:

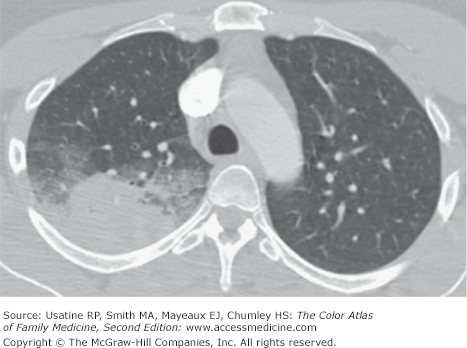

- Lobar—Consolidation involves the entire lobe (Figures 53-1, 53-2, 53-3, 53-4, and 53-5). A cavity with an air-fluid level is sometimes seen within the area of consolidation representing abscess formation (Figure 53-5).

- Bronchopneumonia—Patchy involvement of one or several lobes that may be extensive (Figures 53-6 and 53-7), usually in the dependent lower and posterior lungs (Figure 53-3).

- Interstitial pneumonia—Inflammatory process involves the interstitium; usually patchy and diffuse (Figure 53-8). A nodular interstitial pattern is seen in patients with histoplasmosis (Figure 53-9), miliary TB, pneumoconiosis, and sarcoidosis.

- Miliary pneumonia—Numerous discrete lesions from hematogenous spread (see tuberculosis) (see Chapter 54, Tuberculosis).

Figure 53-2

CT scan of the patient in Figure 53-1 demonstrating a confluent region of lung consolidation with ground-glass opacification on the margins of the consolidated lung commonly seen in bacterial pneumonia. (From Miller WT Jr. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2006:218, Figure 5-1 C. Copyright 2006.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree