105

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Although the fields of adolescent treatment in general and adolescent treatment outcomes research in particular are still in their early stages, recent progress has been considerable. Advances have been made in assessment, appreciation of adolescent-specific treatment needs, and development of particular adolescent treatment modalities and techniques. Over the past 25 years, much has been learned about the effectiveness and limitations of current adolescent treatment methods and programs.

Compared to the state of the field before 1990—when the effectiveness of adolescent treatment was largely a matter of clinical anecdote, intuition, and deeply held conviction—treatment for adolescent substance use disorders now has clearly and repeatedly been shown to be effective. Reviews of the published literature have shown favorable outcomes out to 1 year following treatment and beyond, across various modalities and levels of care. These results are further enhanced by favorable comparisons of treatment groups to waiting-list controls, substance-specific treatments to nonspecific treatment controls, treatment completers to noncompleters, treatment engagers to nonengagers, and carefully organized research-based treatment to loosely organized “treatment as usual” (1–7).

It also is well established that favorable outcomes in treatment of adolescent substance use (including both abstinence and reductions in substance use short of abstinence) are associated with substantial reductions in adolescent morbidity and improvements in psychosocial function. Such improvements in function extend to school, family, criminal behaviors, psychological adjustment, and other psychosocial domains (5,8).

While the research to date on adolescent addiction treatment has been very encouraging, there has been very little comparative examination of the broad range of current treatment modalities, levels of care, and program models. Little is known about the differential effectiveness of various treatment strategies, intensities, and treatment program components (9). Perhaps most important, little empirical work has been done to explore hypotheses of adolescent treatment matching and placement. Nevertheless, questions of which patient should receive what treatment have been the subject of extensive expert consideration, with progressive agreement on fundamental principles and approaches. For example, work with adults consistently shows that assessment-based stratification of severity can predict treatment response (10,11). Using insights such as this, consensus-based “best practices” in the area of adolescent treatment matching and placement are steadily improving. This chapter provides an introduction to the developing area of adolescent treatment matching and placement, with special attention to one particular placement tool, the adolescent patient placement criteria developed by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM).

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS IN ADOLESCENT PLACEMENT

One of the most important advances in the field of adolescent treatment is the articulation of approaches that are developmentally specific to the adolescent population. These respond to the principle that adolescents must be approached differently from adults because of differences in their levels of emotional, cognitive, physical, social, and moral development.

Examples of developmental issues that are fundamental to adolescent assessment and treatment include the extremely potent influence of peers and family. Thus, it is critical that adolescent assessments include collateral informants, to augment and clarify (and, often, correct) the history as presented by the adolescent patient. Such key informants may include family, peers, adult friends or surrogate parent figures, school and court officials, court-appointed special advocates, social service workers, and previous treatment providers.

Adolescents’ use of substances frequently impairs their emotional and intellectual growth. Substance use can prevent a young person from completing the maturational tasks of adolescence, which involve formation of personal relationships, acquisition of social skills, psychological development, identity formation, individuation, education, employment, and family role responsibilities. It is one of the special challenges and unique opportunities of adolescent treatment to modify risk factors that are still actively evolving. Adolescent treatment thus often requires habilitative rather than rehabilitative approaches, emphasizing the acquisition of new capacities, rather than the restoration of lost ones.

Younger adolescents have a very narrow view of the world, with little capacity to think of future implications of present actions. Some adolescents may adopt a pseudo-mature (“streetwise”) posture, despite their overall immaturity. Adolescents who live in a chaotic family system may have difficulties with normative expectations of behavioral contingency. Adolescents who have various cognitive difficulties may be delayed or impaired in acquiring abstract thinking. Attempts to reason with an adolescent about the long-term health effects of substance use usually are futile because the adolescent is unable to appreciate such long-term consequences.

These and other developmental issues make adolescents particularly vulnerable. They typically require greater amounts of external assistance and support than adult patients, both to protect them from the sequelae of substance use and to engage them in the recovery process. Most have not yet acquired the skills for independent living and, even without the impairments associated with substance use, must rely heavily on the guidance of adults.

In general, for a given degree of severity or functional impairment, adolescents require greater intensity of treatment than adults. This is reflected in clinical practice by a greater tendency to place adolescents in more intensive levels of care.

Transitional Age Youth

The definition of adolescence is better understood as a matter of a dimensional developmental stage, rather than a categorical cutoff of chronologic age. Some youth transition out of adolescence into more adultlike functioning earlier than average, some later. On the other hand, it is useful to have some approximate age range in mind for practical purposes, even if somewhat arbitrary. Also, age range definitions may be written into local regulatory language. In general, most regulatory definitions encompass the ranges of 13 to 18 or 13 to 21, with some local variation. From a clinical perspective, these ranges should be viewed flexibly. Although payers or regulators may sometimes choose to apply a definition based on a rigid application of an age cutoff, such as age 18, there are many cases where individual variation and the functional immaturity of a particular patient dictate that the adolescent criteria would be more appropriately applied to a 20- or 21-year-old than the adult criteria.

Additionally, there are another whole set of issues that distinguish an intermediate group of young people—young adults or transitional age youth. These are a group of older, maturing adolescents and younger “20-somethings” who have a foot in both worlds, adolescence and adulthood, and are making a messy, inexact transition. The age range might roughly be considered 17 to 26, with a great deal of individual variation, depending on the functional maturity level. They often are often simultaneously emerging into independence while still relying in large part on the support of parents or other caregiving adults.

The mixed features of both adolescence and adulthood for transition age youth require a special approach. Some providers have begun to develop specialized programming for this group and its unique clinical needs. Eventually, the separation of a third category (adolescent, adult, and transition age youth) of developmental programming may become standard. The tensions inherent in their transition often require a balancing act, especially between emerging independence and persistent dependence. For example, issues of confidentiality versus open sharing of information with parents/caregivers are common. Other common issues include financial support, shared living environments with parents, and extension of standard insurance coverage under parental policies until age 26 with the Affordable Care Act. These tensions and the dynamic interplay between youth and parents are dramatized in the caricatured quotes: “I’m old enough to take care of myself…” versus “You may think you’re all grown up, but as long as you’re living under my roof…”

THE ASAM PATIENT PLACEMENT CRITERIA

The ASAM’s Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders, Second Edition—Revised (ASAM PPC-2R; 12) is a clinical guide that has been widely adopted to assist in matching patients to appropriate treatment settings. It contains separate sets of criteria for adolescents and adults. The criteria, which have undergone evolutionary change and improvement since publication of the first edition in 1991, rest on the concept of enhancing the use of multidimensional assessments in placement decisions by organizing the assessment of the substance-using adolescent into six dimensions and specifying appropriate placements according to gradations of problem severity within each dimension.

Assessment-Based Treatment Matching and Clinical Appropriateness

The ASAM criteria use decision rules to guide placement in specified levels of care, which exist along a continuum. They also attempt to standardize some of the program specifications for each level of care, including some guidelines for minimum staffing levels and general program components. They do not, however, specify these in detail, nor do they attempt to prescribe program models, approaches, or techniques.

Because the elements of assessment in the PPC-2R are not concretely operationalized (as they would be, for example, in standardized instruments of known psychometrics), they certainly allow for and require the use of considerable clinical judgment. They are best used as illustrations of underlying principles of matching, rather than as exact prescriptions or rigid rules.

The ASAM criteria also attempt to avoid assumptions regarding the length of service and treatment dose. Rather, they provide guidelines in the form of general decision rules for continued service and discharge/transfer, which are applied to the original admission problems in the six assessment dimensions that led to the initial treatment placement. Under these decision rules, a patient should remain at a given level of care as long as the problems that created the need for admission persist (or new problems requiring that level of care emerge). We may eventually develop knowledge about minimal or optimal doses for various modalities or levels of care, but little work has been done in that area.

The principal goal of the ASAM criteria is to facilitate the process of matching patients in need of treatment for substance use disorders with appropriate treatment services and settings, in order to maximize the accessibility, effectiveness, and efficiency of the treatment experience. The principle of matching on which the criteria are based is that of clinical appropriateness, which emphasizes quality and efficiency over cost. The concept of “clinical appropriateness” contrasts with the more familiar concept of “medical necessity,” which has become associated with restrictions on utilization. “Medical necessity” has typically been interpreted in terms of avoiding life-threatening imminent danger and is related primarily to acute medical or psychiatric concerns (Dimensions 1, 2, and 3). In contrast, “clinical appropriateness” conveys the notion that patients should be treated in the most suitable placements, defined by the extent of their problems and priorities in all six of the ASAM assessment dimensions.

The criteria reflect a tension between an attempt to promote a broader continuum of treatment services on the one hand and an attempt to reflect the real world of treatment service delivery on the other. As a result, the criteria do not articulate some of the innovative sublevels of intensity and treatment settings that should exist (and in some places already do exist). However, even the “limited” continuum of treatment settings described in the criteria is not yet available in most communities.

The reality of limited availability of services is, of course, a major problem, particularly in the treatment of adolescents. One or more of the levels of care may not exist or be accessible in a given community, in either rural or urban settings. Funding limitations and other resource constraints also are barriers to the availability of a needed treatment setting. Even logistical issues such as waiting lists can render a treatment setting unavailable, and the individual variations in programs within the level of care categories might sometimes mean that specific needed treatment services are unavailable even if an available setting meets the criteria more generally.

When the criteria designate a treatment placement that is not available to a given patient, a strategy must be crafted to provide the patient the needed services in another placement or combination of placements, always erring on the side of safety and effectiveness. This may require increasing the intensity of services, usually through placement at a more intensive level of care.

One of the criticisms of previous editions of the criteria has been that it was too heavily oriented toward private sector and managed care environments. All too frequently, the continuum of services described and the range of benefits implied in the criteria are not available to disadvantaged or public sector populations. However, the ASAM PPC-2R outlines a full range of treatment services appropriate to the needs of all drug-involved adolescents, whether they are privately insured, publicly insured, underinsured, or uninsured. Although they may not have access to it, many indigent adolescents may need an even broader continuum of services than those with greater resources. In general, adolescents with fewer supports, less resiliency, and lower levels of baseline functioning may need a higher intensity of services and longer lengths of service at all levels of care than do those with the benefits conferred by economic advantage.

One goal of the ASAM criteria has been to more explicitly encompass the circumstances of adolescents in the public sector. For example, there are specific references to adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system, where many adolescents may have had extended periods of enforced abstinence, but usually have not had active treatment. In this context, the ascertainment of severity and treatment needs should not be made by a narrow standard based on recency of use, but rather by a full multidimensional assessment that emphasizes the adolescent’s acquisition of recovery skills and capacity for reintegration into the community. Hopefully, active treatment, including the full continuum of care reflected in the ASAM PPC-2R, will increasingly become the rule rather than the exception for adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system.

Treatment at every level of care requires coordination of a broad array of interrelated treatment services to respond to the needs of the individual patient. This is sometimes accomplished by direct provision of multiple treatment services, and sometimes by linkages with other service providers, usually through referral. Examples include psychiatric assessment and treatment, medical assessment and treatment, establishment of a primary care medical “home,” psychological and/or educational testing for learning disorders, special or alternative education services, family therapies, juvenile justice probation and supervision, foster care support services, public benefit coordination or other social service agency interventions, vocational and prevocational training, child care, and transportation. In general, the greater the adolescent’s severity, the greater the need for such broad and diverse adjunctive services. To deliver this array of services, treatment programs at all levels of care should develop active affiliations with programs and agencies that offer other services or levels of care and should help patients access treatment fluidly across the continuum. Barriers to treatment integration remain a fundamental and profound problem for the field, which are only recently beginning to be addressed, at least partially in response to adoption of the ASAM criteria by state agencies, third-party payers, and treatment providers.

Placement and Treatment Considerations by Assessment Dimension

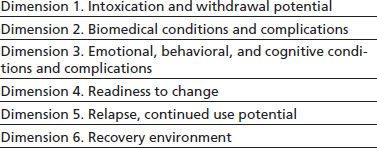

As discussed earlier, the ASAM criteria organize the assessment of the substance-using adolescent into six dimensions, specifying appropriate placements according to gradations of problem severity within each dimension (Table 105-1).

TABLE 105-1 ASAM PPC ASSESSMENT DIMENSIONS

Dimension 1: Intoxication and Withdrawal

The PPC-2R includes expanded details of the Dimension 1 assessment elements with some breakdown by specific drug classes. This highlights the range of intoxication and withdrawal symptoms, which all too often are overlooked in adolescents, and emphasizes the importance of their treatment. Some clinically prominent examples include memory impairment caused by marijuana intoxication, which can persist for many weeks following abstinence (substance-induced persisting amnestic disorder); sensory disturbance or “flashbacks” caused by hallucinogens, which can persist for weeks to months following abstinence (substance-induced perceptual distortion); and delirium and other states of cognitive disorganization caused by inhalants, which can persist for weeks or more following abstinence. Another very common example is insomnia as a symptom of extended subacute withdrawal from various substances (including marijuana, opioids, and alcohol), which, although not typically thought of as a very severe problem, can be a powerful trigger for relapse.

The approach to detoxification services in the ASAM adolescent criteria is different from that used in the adult criteria, where such services are described in a separate, discrete set of detoxification criteria. Detoxification is integrated into the adolescent criteria because severe physiologic withdrawal and the need for its management are seen less frequently in adolescents than in adults, given typical patterns of use and duration of exposure. Therefore, the provision of detoxification as an “unbundled” or stand-alone service is less common and less needed with adolescents. Nevertheless, withdrawal does occur in adolescents and should not be overlooked. In such cases, the provision of services to manage the withdrawal in a setting separate from other treatment services is clinically undesirable because of the developmental issues involved in the care of adolescents. Moreover, there is no evidence that the kinds of ambulatory detoxification treatments that have become increasingly common for severe withdrawal in adults are effective or desirable in the adolescent population.

While most adolescents do not develop classic or well-defined physiologic withdrawal symptoms, they may be more susceptible than adults to the development of substance dependence syndromes, including physiologic tolerance. Adolescents have a one in four chance of developing one of the DSM-IV symptoms of dependence later in life if exposed to alcohol, marijuana, or nicotine before the age of 15 and four to eight times the risk of those not exposed until after age 17 (13). Also, the progression from casual use to dependence can be more accelerated in adolescents than in adults, as well as the progression from dependence on one substance to others (14).

The process of detoxification includes not only the attenuation of the physiologic and psychological features of intoxication and withdrawal syndromes but also the process of interrupting the momentum of habitual compulsive use in adolescents. Because of the force of this momentum and the inherent difficulties in overcoming it even when no clear physiologic withdrawal syndrome is seen, this phase of treatment frequently requires a greater initial intensity in order to establish treatment engagement and patient role induction. This is critical to the success of treatment because it is so difficult for patients to engage or participate in treatment while caught up in the cycle of frequent intoxication and recovery from intoxication.

Dimension 2: Biomedical Conditions and Complications

While the medical sequelae of addiction generally are not as common or as severe in adolescents as in adults, they certainly need to be considered in treatment placement decisions. Some of the more severe acute and subacute medical complications of substance use include seizures caused by stimulant and inhalant intoxication, traumatic injuries (either accidental or due to victimization) associated with any substance intoxication, and respiratory depression caused by opioid overdose (which is increasingly common with cheaper, purer supplies of heroin as well as the increased popularity of diverted prescription opioids, such as sustained-release oxycodone [OxyContin]). Acute alcohol poisoning is a severe medical complication that is more typical of adolescents than adults. The sequelae of injection drug use are well known, including cellulitis, HIV, endocarditis, and hepatitis B and especially hepatitis C.

Some of the less severe but more common (and often underrecognized) medical sequelae of substance use include gastritis caused by alcohol use, exacerbation of reactive airway disease caused by smoking marijuana, dental disease caused by poor self-care, and weight loss and malnourishment caused by self-neglect and/or the appetite-suppressing properties of certain drugs. Another notable area of medical complication in adolescents is the exacerbation of chronic illness (such as diabetes, asthma, or sickle cell disease) that results from impaired self-care and poor compliance with indicated medical treatments.

High-risk sexual behaviors are a major problem in adolescents. The associated sexually transmitted diseases commonly seen include chlamydial and gonococcal infections, syphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, HIV, and hepatitis B (HBV). Both urethritis in boys and cervicitis in girls are relatively common, but frequently overlooked because they are often asymptomatic. The special needs and medical vulnerabilities of pregnant substance-using teenagers require particular care in selecting treatment services. Overall, the need for contraception and other medical prevention and treatment services related to sexual behaviors in drug-involved adolescents cannot be overemphasized.

Dimension 3: Emotional, Behavioral, and Cognitive Conditions and Complications

Drug-involved adolescents typically demonstrate a very high degree of co-occurring psychopathology, which frequently does not remit with abstinence. Many experts estimate that rates of psychiatric comorbidity, or dual diagnosis, are higher in adolescents than in adults (15). Comorbidity should be considered the rule rather than the exception. As in adults, the line between substance abuse treatment and mental health treatment is increasingly blurring, and the need for co-occurring enhanced, or combined behavioral health programming, is great. Although our evidence base for co-occurring treatment is limited compared to that for adults, it is growing. For example, there is mounting evidence that identifying and treating depression in substance-involved youth improve substance use outcomes and vice versa. Another example is our growing awareness of the psychiatric sequelae of marijuana use in youth and our growing clinical suspicions that these problems are much worse with synthetic cannabinoids (“K2,” “spice,” etc.)

Even adolescents who have not been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (either because they have not yet had a formal psychiatric evaluation or because subsyndromal symptoms do not meet diagnostic criteria) often have problems in Dimension 3 that need to be considered in making treatment decisions. Examples include hyperactivity or distractibility without a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mood lability and explosive temper without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, or dysphoric mood and loss of interests without a diagnosis of depression. Various nonspecific symptoms—such as problems with anger management or impulse control, suspiciousness, and social withdrawal—also may be substance induced or substance exacerbated. And the nonspecific features of immature and/or impaired executive functioning are very common in drug-involved adolescents, including impulsiveness, explosiveness, poor affective self-regulation, poor strategic planning, disinhibition, and the like, even if the descriptive taxonomy of the psychiatric DSM is still primitive in this regard.

The inclusion of cognitive conditions in Dimension 3 emphasizes the importance of cognitive abilities, as well as global or focal cognitive impairments, in an adolescent’s functional capacity. Whether cognitive problems are due to preexisting conditions (such as borderline intellectual functioning, fetal alcohol effects, assorted attentional deficits, or learning disorders) (16,17) or are complications of substance use (such as marijuana-induced amnestic disorder), they often contribute to the severity of substance use disorders and interfere significantly with treatment and recovery.

To be most effective, physicians and treatment programs must adapt their methods and strategies to respond to adolescents’ cognitive vulnerabilities and strengths. It also is critical to consider cognitive function in a developmental perspective, because cognition evolves dynamically over time.

One of the keys to treating adolescents is to use methods that take into account the ways that they learn, responding to issues of normal adolescent development, as well as the delayed development and immaturity that often accompany drug use and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. In general, the delivery of most therapies should be broken down into time-limited components, with frequent breaks, taking into account limitations in youngsters’ attention spans. Adolescent engagement and learning are promoted by the use of experiential recovery activities that involve active participation rather than passive reception of information and that are somewhat energetic, noisy, and fun while at the same time delivering serious therapeutic content. Engagement also is enhanced by the acknowledgement and even partial endorsement of adolescent culture, including its typical stance of nonconformity with adult and mainstream norms.

Behavior and its management are another prominent developmental feature of adolescent treatment in Dimension 3. While the expectation of adult, or mature, behavior may be questionable in adult treatment settings, it is certainly absurd in adolescent settings. The acquisition of self-regulation skills is an essential goal of treatment for substance users of all ages, but it also is a work in progress for all adolescents, even without substance use. Adolescent treatment programs must constantly seek a balance between an emphasis on limit setting and some degree of tolerance for chaos, as part of the necessary recognition that adolescents still are partly children. Moreover, the penchant for mischief among youngsters is not always an indicator of antisocial traits. On the other hand, careful assessment of the broad range of adolescent misbehavior forms the basis of very powerful treatment interventions that target improvements in family monitoring, supervision, and behavioral management.

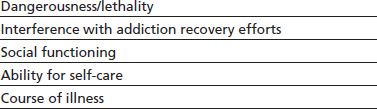

In the ASAM PPC-2R, Dimension 3 has been expanded and divided into new subdomains for greater emphasis on psychiatric comorbidity or “dual diagnosis” issues. These subdomains are intended to enrich the detail and guide the assessment of risk and treatment needs for emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems. The organization of the Dimension 3 severity specifications by subdomains emphasizes that placement decisions emerge out of the assessment of symptomatic functional impairment rather than any specific categorical diagnosis (Table 105-2).

TABLE 105-2 DIMENSION 3 SUBDOMAINS

For example, the subdomain titled “Dangerousness/ Lethality” refers to the extent of risk of imminent harm to self or others. Assessment considerations may include suicidality, assaultiveness, risk of victimization, and exposure to the elements. Treatment decisions in this subdomain focus on safety and protection from dangerous consequences and may include such interventions as residential containment or high-intensity family monitoring between outpatient sessions.

The subdomain titled “Interference with Addiction Recovery Efforts” refers to the extent to which psychological and behavioral symptoms are a distraction from treatment participation or engagement. Examples include difficulty attending to treatment sessions because of problems with concentration, difficulty in completing recovery assignments or absorbing treatment materials because of problems with memory or comprehension, inability to attend treatment consistently because of running away, inability to participate in treatment because of disruptive behavior, and distraction caused by preoccupying worries.

The subdomain titled “Social Functioning” refers to the extent to which emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems cause impairments in meeting responsibilities in major social arenas such as family, school, work, and personal relationships. Examples of assessment considerations in this subdomain include problems managing peer or family conflict, legal and conduct problems, problems with truancy or school performance, ungovernability at home, and narrowing of social repertoire and isolation.

The subdomain titled “Ability for Self-Care” refers to the extent to which the adolescent has problems in managing activities of daily living and personal care. Assessment considerations in this subdomain include behaviors associated with patterns of victimization, high-risk or indiscriminate sexual behaviors, disorganization that interferes with emerging independent living skills, poor self-regulation (or poor cooperation with external regulation) of daily routine, and problems with hygiene or nutrition.

The subdomain titled “Course of Illness” refers to an interpretation of the adolescent’s present situation and symptoms in the context of his or her history and response to treatment, with a goal of predicting future course and relative stability. For example, the adolescent’s history may suggest that a mood disorder decompensates rapidly with medication noncompliance, suggesting a higher instability and severity than would be the case if the course deteriorates more slowly and suggesting the need for a more urgent and/or more intensive treatment response. Other examples include an adolescent who has tended to run away soon after an episode of family conflict or an adolescent who tends to relapse to substance use following recurrence of depressive symptoms.

Dimension 4: Readiness to Change

Assessment of treatment readiness is an essential component of treatment matching for adolescents. In the ASAM PPC-2R, Dimension 4 “Readiness to Change” highlights the active, dynamic concept of treatment engagement. Placement decisions based on Dimension 4 will include consideration of whether the adolescent (and related systems, such as the family) is in the “precontemplation,” “contemplation,” “preparation,” or “action” stage of change.

In general, it is likely that effective interventions will be different at various stages of readiness for change. On the whole, adolescents tend to present at earlier stages of readiness to change than do adults because of developmental context. For example, it is external pressures that push them into treatment even more so than adults (18).

It is important to emphasize that engagement and role induction are critical components of treatment. Significant advances have been made in expanding the treatment engagement repertoire from simply and inflexibly attempting to overcome the adolescent’s resistance to appreciating the adolescent’s own set of motivations and goals and attempting to enroll those into an evolving treatment agenda. Motivational interviewing and other motivational enhancement techniques have formed the basis of a variety of intervention models at various levels of care, including early intervention (19) and outpatient treatment (20).

Assessments of readiness to change should take into account a variety of change processes, including the processes used by adolescents themselves in effecting self-change (21), the processes used by families in effecting change (22), and the processes used by the external systems that interact with adolescents and their families, such as the coercive influence of the juvenile justice system. It is common to consider readiness for change as a balance of internal experiential contingency motivations (such as social frustrations; symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal; loss of achievements, interests, and enjoyment; unpleasant or frightening experiences, including violence, victimization, high-risk motor vehicle use, or unwelcome sexual experiences) and external contingency motivations (such as parental mandates, legal threats, drug testing, peer group affiliations and influences, and loss of status). The question is which of these factors (and others) will have salience and how and in what setting to make best use of them in enhancing the adolescent’s motivation for treatment and change. Additional factors in treatment engagement include problem identification, help-seeking orientation, self-efficacy, and hopefulness. Cultural factors also are important components in assessing readiness to change, as they influence likelihood of seeking and receiving treatment, likelihood of perceiving treatment as helpful, and consideration of cultural context in devising treatment engagement strategies.

Dimension 5: Relapse, Continued Use, or Continued Problem Potential

Dimension 5 entails an estimation of the likelihood of resumption or continuation of substance use. The assessment of relapse potential (or, reciprocally, remission potential) should include a number of key factors. Although not incorporated directly into the criteria, a schema for incorporating four subdomains for more detailed PPC-2R Dimension 5 assessments has been proposed (11, p. 345). These subdomains are as follows: (a) historical pattern of use (including amount, frequency, chronicity, and treatment response), (b) pharmacologic response to the effects from particular substances (including positive reinforcement such as pleasure with use and cravings and negative reinforcement such as relief from withdrawal or other negative experiences), (c) response to external stimuli (including reactivity to environmental triggers and acute or chronic stress), and (d) cognitive and behavioral vulnerability and resiliency factors (including traits of impulsivity, passivity, locus of control, and overall coping capacities).

The “historical pattern of use” concept is similar to the “course of illness” subdomain in Dimension 3. That is, history and treatment response are likely to predict the future course of illness, including relapse potential. For example, some adolescents are more likely to have a rapid course of full reinstatement of dependence with severe impairment following a single lapse episode, while others are likely to have a more indolent course, with only gradual escalation of use. This suggests one means of informing treatment- and placement-matching decisions on an individualized basis. Response to past treatment also may be a way of using individualized treatment effectiveness as a guide to placement: If a particular dose of treatment or modality or level of care led to a significant period of improvement for an adolescent in the past, then it may suggest the appropriateness of repeating that treatment following a relapse or exacerbation. On the other hand, if a particular dose or placement was not effective in the past, this history may suggest the need for a more intensive intervention.

Dimension 6: Recovery/Living Environment

Dimension 6 aims to assess the ability of the adolescent’s home environment to support or impede treatment and recovery. For adolescents, the most important features of the recovery environment generally involve family and peers. The need for inclusion of families or other caretakers in assessment and treatment is paramount. In many cases, it is unreasonable to expect that the adolescent will be the initial or most important locus of change. Rather, it often is more effective to help the family improve its approach to monitoring, supervision, and home intervention, with the expectation that the family as the primary locus of change will in turn change the adolescent.

Families, and their needs and involvement, should be considered broadly to encompass a wide range of circumstances, such as extended families, surrogate families, and other caretakers. It also is important to address cultural context and to use cultural competence as a critical tool for engaging families in treatment.

Problems in Dimension 6 that typically affect placement include chaotic home environments in which substance use, illegal behaviors, abuse, neglect, and lack of supervision are prominent or a broader community in which substance use and crime are endemic. Many adolescents have a social network composed primarily or even exclusively of family members or peers who are involved in substance use or criminal behaviors. This social context may portray deviance as normative. There may not be readily apparent role models for the rewards of abstinence. Some adolescents may have had no experience of living in an environment that fosters healthy prosocial development and functioning.

There is an acute shortage of availability of services that provide recovery environment support for youth. These structured, protective living environments are frequently vital to support ongoing treatment that might be integrated into the living environment itself or more commonly coordinated with programming off-site. Frequently, they serve the function of a supervised context where adolescents can sustain and rehearse therapeutic gains initiated at a more intensive level of care. This need for step-down, lower-intensity residential support is perhaps even more vital in the continuum of care for youth than for adults because of their lack of independence and reliance on the support or partial support of caregiving adults. For younger adolescents, these programs would typically be level 3.1 (see below for description of that level of care), often group homes or similar programs. For young adults, these programs could also be level 3.1. But there is also a need for less intensive Recovery Housing programs, with more supervision than typical adult-style self-organized sober housing (e.g., Oxford Houses), or adult-style Recovery House boarding houses that have minimal supervision, but perhaps with less intensity than the typical 3.1 or halfway house.

Placement and Treatment Considerations by Levels of Care

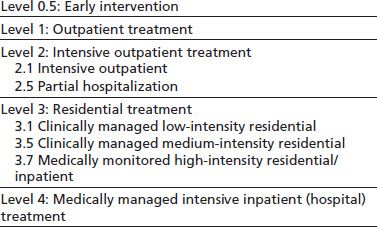

The adolescent levels of care in the ASAM PPC-2R are similar to the levels of care described and endorsed in other expert consensus documents (23) (Table 105-3).

TABLE 105-3 ASAM PPC2-R ADOLESCENT LEVELS OF CARE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree