Physiology of Cells

MOVEMENT OF SUBSTANCES THROUGH CELL MEMBRANES

If a cell is to survive, it must be able to move substances to where they are needed. We already know one way that cells move organelles within the cytoplasm: pushing or pulling performed by the cytoskeleton. A cell must also be able to move various molecules in and out through the plasma membrane, as well as from one membranous compartment to another within the cell. In this first part of the chapter, we explore some of the basic mechanisms a cell uses to move substances across its membranes.

Before beginning a discussion of individual processes, we must realize that membrane transport processes can be labeled as passive or active. Passive processes do not require any energy expenditure or “activity” of the cell membrane—the particles move by using energy that they already have. Active processes, on the other hand, do require the expenditure of metabolic energy by the cell. In active processes the transported particles are actively “pulled” across the membrane. Keep this distinction in mind as we explore the basic mechanisms of cell membrane transport.

Passive Transport Processes

DIFFUSION

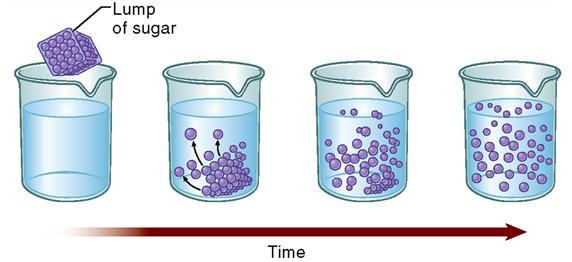

Often, molecules simply spread or diffuse through the membranes. The term diffusion refers to a natural phenomenon caused by the tendency of small particles to spread out evenly within any given space. All molecules in a solution bounce around in short, chaotic paths. As they collide with one another, they tend to spread out, or diffuse. Think of the example of a lump of sugar dissolving in water (Figure 4-1). Right after the lump is placed in the water, the sugar molecules are very close to one another—the sugar concentration in the lump is very high. As the sugar molecules dissolve, they begin colliding with one another and thus push each other away. Given enough time, the sugar molecules eventually diffuse evenly throughout the water.

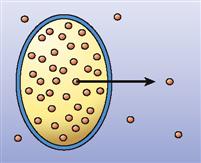

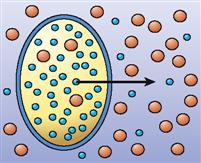

Notice that during diffusion, molecules move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. It is not surprising, then, that molecules tend to move from the side of the membrane with high concentration to the side of the membrane with a lower concentration of that molecule. Another way of stating this principle is to say that diffusion occurs down a concentration gradient. A concentration gradient is simply a measurable difference in concentration from one area to another. Because molecules spread from the area of high concentration to the area of low concentration, they spread down the concentration gradient.

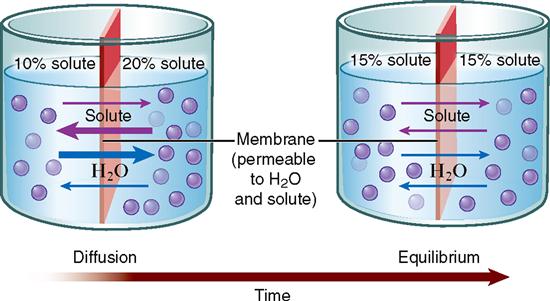

Perhaps the best way to learn the principle of diffusion across a membrane is to look at the example illustrated in Figure 4-2. Here we have different mixtures of a solute (dissolved substance) in water. Suppose a 10% solute mixture is separated from a 20% solution by an artificial membrane. Suppose further that the membrane has pores in it that allow solute molecules to pass through, as well as pores that allow water molecules to pass. Solute particles and water molecules darting about the solution collide with each other and with the membrane. Some inevitably hit the membrane pores from the 20% solute side, and some hit the membrane pores from the 10% side. Just as inevitably, some pass through the pores in both directions. For a while, more solute particles enter the pores from the 20% side simply because they are more numerous there than on the 10% side. More of these particles, therefore, move through the membrane from the 20% solute solution into the 10% solute solution than diffuse through it in the opposite direction. In other words, the overall direction of diffusion is from the side where the concentration is higher (20%) to the side where the concentration is lower (10%).

During the time that diffusion of solute particles is taking place, diffusion of water molecules is also going on. Remember, the direction of diffusion of any substance is always down that substance’s concentration gradient. Water molecules are more concentrated on the 10% solute solution side because the solution is more dilute—or watery—on that side. Thus water molecules move from the 10% solute solution side to the 20% solute solution side. As Figure 4-2 shows, diffusion of both kinds of molecules eventually produces a dynamic form of equilibrium in which both solutions have equal concentrations. We say that equilibration has occurred.

Dynamic equilibrium is not a static state with no movement of molecules across the membrane. Instead, it is a balanced state in which the number of molecules of a substance bouncing to one side of the membrane exactly equals the number of molecules of that substance that are bouncing to the other side. Once equilibration has occurred, overall diffusion may have stopped, but balanced diffusion of small numbers of molecules may continue.

SIMPLE DIFFUSION

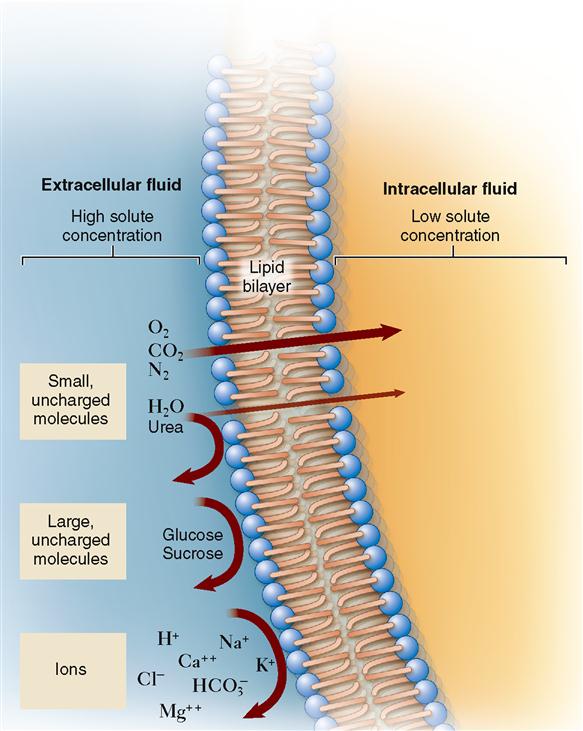

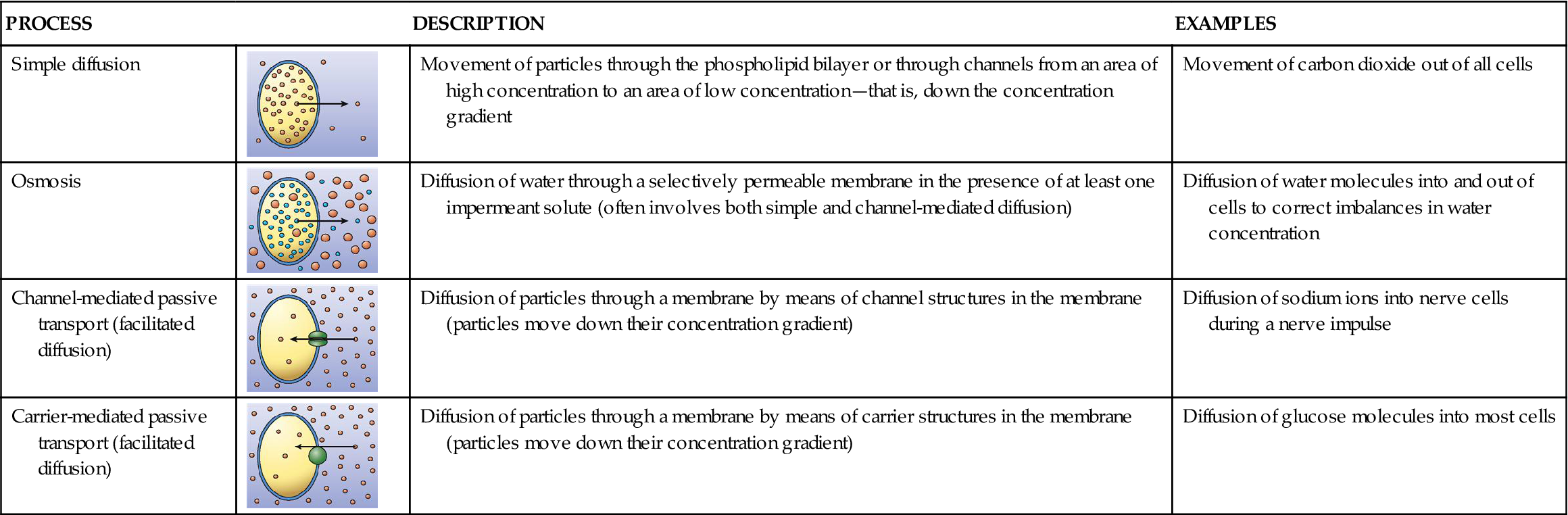

Now that we know that concentration gradients drive diffusion, we can explore how the molecules actually find a way through a cell membrane (Table 4-1). Sometimes molecules diffuse directly through the bilayer of phospholipid molecules that forms most of a cell membrane. As discussed in Chapter 3, lipid-soluble molecules can pass through easily. As Figure 4-3 shows, small hydrophobic molecules such as oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) can diffuse directly through the phospholipid bilayer. Small, uncharged particles such as water (H2O) and urea can diffuse only slightly. Such molecules simply dissolve in the phospholipid fluid, diffuse through this fluid, and then move into the water solution on the other side of the membrane. When molecules pass directly through the membrane, the process is called simple diffusion.

TABLE 4-1

| PROCESS | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLES | |

| Simple diffusion |  | Movement of particles through the phospholipid bilayer or through channels from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration—that is, down the concentration gradient | Movement of carbon dioxide out of all cells |

| Osmosis |  | Diffusion of water through a selectively permeable membrane in the presence of at least one impermeant solute (often involves both simple and channel-mediated diffusion) | Diffusion of water molecules into and out of cells to correct imbalances in water concentration |

| Channel-mediated passive transport (facilitated diffusion) |  | Diffusion of particles through a membrane by means of channel structures in the membrane (particles move down their concentration gradient) | Diffusion of sodium ions into nerve cells during a nerve impulse |

| Carrier-mediated passive transport (facilitated diffusion) |  | Diffusion of particles through a membrane by means of carrier structures in the membrane (particles move down their concentration gradient) | Diffusion of glucose molecules into most cells |

When molecules are allowed to cross a membrane, they are said to permeate the membrane. Thus a particular membrane is permeable to a particular molecule only if it can pass through that membrane. We say that a molecule is permeant if it is able to diffuse across a particular membrane. It is impermeant if it is unable to diffuse across the membrane.

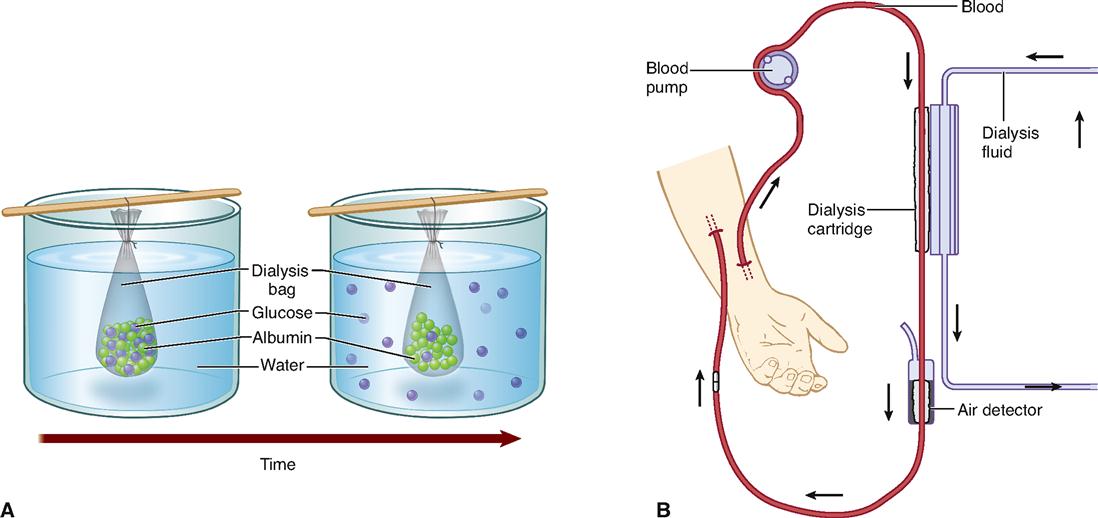

Box 4-1 shows how the process of diffusion can be harnessed to “clean up” the blood after a person’s kidneys fail.

OSMOSIS

A special case of diffusion is called osmosis. Osmosis is the diffusion of water through a selectively permeable membrane. Often, water is able to diffuse across a living membrane that does not allow diffusion of one or more other substances. Thus water is permeant and therefore can equilibrate its concentration on both sides of the membrane, but the impermeant solutes cannot.

But how can this be? If you look at Figure 4-3, you see that water barely passes through phospholipid membranes! In 1988 Peter Agre finally solved this mystery by proving the existence of small water channels in cell membranes called aquaporins (meaning “water pores”). It is the presence of aquaporins that make membranes permeable to water. We will see how such channels allow other substances to move easily across membranes later. For now, let us focus on osmosis—a very important type of diffusion in the body.

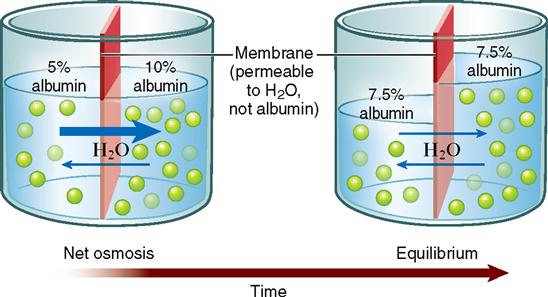

First, let us look at an example of osmosis. Imagine that you have a 10% albumin solution separated by a membrane from a 5% albumin solution (Figure 4-4). Assume that the membrane has water pores and is freely permeable to water but impermeable to albumin. The water molecules diffuse or osmose through the membrane from the area of high water concentration to the area of low water concentration. That is, the water moves from the more dilute 5% albumin solution to the less dilute 10% albumin solution. Although equilibrium is eventually reached, the albumin does not diffuse across the membrane. Only the water diffuses. Because of this osmosis, one solution loses volume and the other solution gains volume (see Figure 4-4).

Unlike the open container pictured in Figure 4-4, cells are closed containers. They are enclosed by their plasma membranes. Actually, most of the body is composed of closed compartments such as cells, blood vessels, tubes, and bladders. In closed compartments, such as a toy water balloon, changes in volume also mean changes in pressure. Adding volume to a cell by osmosis increases its pressure, just as adding volume to a water balloon increases its pressure. Water pressure that develops in a solution as a result of osmosis into that solution is called osmotic pressure. Taking this principle a step further, we can state that osmotic pressure develops in the solution that originally has the higher concentration of impermeant solute.

Potential osmotic pressure is the maximum osmotic pressure that could develop in a solution when it is separated from pure water by a selectively permeable membrane. Actual osmotic pressure, on the other hand, is pressure that already has developed in a solution by means of osmosis. Actual osmotic pressure is easy to measure because it is already there.

Because potential osmotic pressure is a prediction of what the actual osmotic pressure would be, it cannot be measured directly. What determines a solution’s potential osmotic pressure? The answer, simply put, is the concentration of particles of impermeant solutes dissolved in the solution. Thus one can predict the direction of osmosis and the amount of pressure it will produce by knowing the concentrations of impermeant solutes in two solutions.

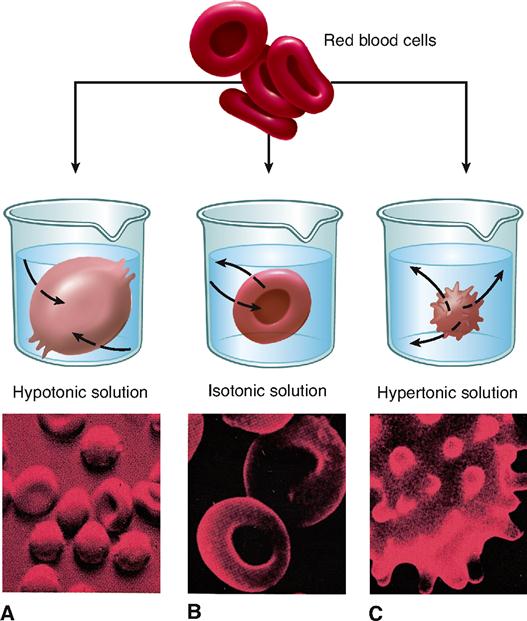

The concept of osmosis and osmotic pressure has very important practical consequences in human physiology and medicine. Homeostasis of volume and pressure is necessary to maintain the healthy functioning of human cells. The volume and pressure of body cells tend to remain fairly constant because intracellular fluid (fluid inside the cell) is maintained at about the same potential osmotic pressure as extracellular fluid (fluid outside the cell). A fluid that has the same potential osmotic pressure as a cell is said to be isotonic to the cell (Figure 4-5, B). Isotonic comes from the word parts iso-, meaning “same,” and -tonic, referring to “pressure.” The isotonic solution and cytosol have the same potential osmotic pressure because they have the same concentration of impermeant solutes.

A human cell placed in a concentrated solution of impermeant solutes will shrivel up. Look at the example of a red blood cell in Figure 4-5, C. The pictured cell is in a solution with a higher concentration of impermeant solutes than that found in the cell and, therefore, has a higher potential osmotic pressure. The extracellular solution is said to be hypertonic (higher pressure) to the intracellular solution (cytosol). Cells placed in solutions that are hypertonic to intracellular fluid always shrivel. If cells shrivel too much, they may become permanently damaged—or even die. Obviously, this fact is medically important. Large amounts of solutes cannot be introduced into the body without considering the effect they will have on the concentration of impermeant solutes in the extracellular fluid. If a treatment or procedure causes extracellular fluid to become hypertonic to the cells of the body, serious damage may occur.

If a human cell is placed in a very dilute solution, such as pure water, the cell may swell. If it expands enough, the cell may burst, or lyse. Look at the example of a red blood cell in Figure 4-5, A. This cell is placed in a solution that is hypotonic (lower pressure) to the intracellular fluid. Hypotonic solutions tend to lose pressure because they have a lower concentration of impermeant solutes, and thus a higher water concentration, than the opposite solution. Water always osmoses from the hypotonic solution to the cytosol.

In summary, we can make several generalizations about osmosis. First, osmosis is the diffusion of water across a membrane that limits the diffusion of at least some of the solute molecules. That is, at least one impermeant solute must be present. Second, osmosis results in the gain of volume (and thus pressure) on one side of the membrane and loss of volume (and pressure) on the other side of the membrane. Third, the direction of osmosis and the resulting changes in pressure can be predicted if you know the potential osmotic pressure or tonicity of the solution outside the plasma membrane.

FACILITATED DIFFUSION

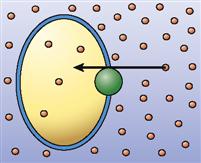

For a long time, biologists thought that simple diffusion was the only way that molecules could diffuse through a cell membrane. They found that water-soluble molecules such as sodium ions (Na+) and glucose molecules could not pass through an artificial phospholipid bilayer easily (see Figure 4-3). However, they also found that indeed such small, water-soluble molecules could pass through living cell membranes quickly. Even water molecules, which pass through the thin phospholipid membrane only rarely, diffuse very rapidly through most living cell membranes. It was not until the presence of various transport proteins, such as membrane channels and membrane carriers, was discovered that we understood how these molecules diffuse across cell membranes. These membrane transporters enable a kind of mediated passive transport that is often called facilitated diffusion.

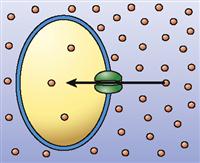

Channel-Mediated Passive Transport

As you already know, cell membranes possess protein “tunnels,” better known as membrane channels (see Table 3-4, p. 72, and Figure 4-6). Membrane channels are pores through which water molecules, specific ions, or other small, water-soluble molecules can pass. For example, sodium ions (Na+) pass only through sodium channels and chloride ions (Cl−) pass only through chloride channels. Recall that water diffuses through aquaporins, which are water-specific channels, during osmosis. Membrane channels can exhibit such specificity because their molecular structure prevents molecules of the wrong shape and the wrong pattern of charges to pass through the channel. Thus living membranes can be permeable to some molecules but not to others, depending on the type of channels present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree