41

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ CHARACTERISTICS OF ADDICTED PHYSICIANS

■ THEORIES OF ADDICTION AMONG PHYSICIANS

■ IDENTIFICATION, INTERVENTION, AND ASSESSMENT

The available research about addiction among physicians and physician health programs (PHPs) is extensive and has been well documented in several excellent overviews (1–6,127). Bissell and Haberman (7), Angres et al. (8), Nace (9), and Coombs (10) have written complete texts about addiction in physicians and other health professionals. Physicians are a convenient population to study; they are accessible both prior to and after treatment and are articulate about their disease. Research on physician addiction elucidates the natural course of addiction in a highly regulated and monitored population. At the same time, physicians differ from the general population in terms of education, income, and regulatory oversight; therefore, conclusions about the efficacy of addiction treatment among physician-patients cannot simply be generalized to the population at large. However, the highly structured and consistent treatment model developed for the care of this population does provide clues for treatment improvement. DuPont et al. (11) have suggested that a model that utilizes the PHP experience should be an integral part of the gold standard for effective treatment.

PREVALENCE

We have 20 years of debate about the actual and changing prevalence of addiction among physicians (12). Kessler et al. (13) reported that 3.8% of the general population at any given time has any substance use disorder and 1.3% meets criteria for alcohol dependence and 0.4% for drug dependence. Lifetime prevalence has been estimated at between 8% and 13% in the general population. Studies that attempt to determine the prevalence of addiction in physicians are based upon anonymous questionnaires (12,14–21). Hughes et al. (19) reported a lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence and drug abuse or dependence in physicians at 7.9%, somewhat less than the percentage reported in the general population by Kessler (13). However, methodologic differences may account for the observed differences. The Hughes study surveyed 9,600 physicians by mail with a lower response rate (59%) and relied on honest and denial-free reports by the physician self-report; the Kessler general population study utilized face-to-face interviews with trained interviewers.

In 1970, Vaillant et al. (22) reported on the types of substances physicians use. At that time, he noted that physicians were just as likely to smoke cigarettes and drink alcohol as the general population but more likely to take tranquilizers and sedatives. In a more comprehensive study 29 years later, Hughes et al. (17) noted that physicians were less likely to smoke cigarettes than nonphysicians and more likely to consume benzodiazepines and opioids. The change in cigarette use was presumably due to increasing medical data about the health risks and changes in physician attitude regarding tobacco. The decrease in smoking was also found by Mangus et al. in 1998 (23). Hughes et al. (19) stated that physicians drink more alcohol than the general population; the authors attributed this in part to their higher socioeconomic status. They also noted that 11.4% of physicians had used unsupervised benzodiazepines and 17.6% reported the unsupervised use of opioids. Vaillant (24), in his commentary on the Hughes study, rang an alarm bell by stating “physicians are five times as likely [than the general population] to take sedatives and minor tranquil-izers without medical supervision.” The use of opioids and minor tranquilizers commonly begins prior to or in medical school, since medical students use more of these drugs than age-matched cohorts (25). Clark examined substance abuse in medical students using a 4-year longitudinal study (26). Eighteen percent met the study’s criteria for alcohol abuse in the first 2 years of medical school. They reported that a family history of alcoholism was associated with alcohol abuse in the medical student.

Another view of physician abuse of alcohol and drugs can be derived from complaints reviewed by state medical boards. Morrison and Wickersham (27) noted that 14% of board disciplinary actions were alcohol or drug related, and another 11% were due to inappropriate prescribing practices—many of which are also addiction related. In 2003, Clay and Conatser (28) reported similar disciplinary rates, with 21% due to alcohol and drug issues and 10% due to inappropriate prescribing or drug possession.

Alcohol- and drug-related work impairment was the primary impetus for the formation of state PHPs in the United States and continues to account for the majority of physician impairment cases seen by most PHPs today (2). David Canavan, MD started the first PHP (New Jersey) in 1982. Since that time, “all but three of the 54 US medical societies of all states and jurisdictions had authorized or implemented impaired physician programs” (29). The most recent PHP (Georgia) opened its doors in 2012. In 2008, California moved against this trend by dissolving its PHP (30).

Ethnic variation in substance abuse in the general population is described in the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions: Whites, Native Americans, and Hispanics have a higher prevalence of dependence than Asians; but no published data about physician addiction have been reported to date using ethnicity as an independent variable.

In summary, though the prevalence of addiction to all chemicals appears to be about the same as in the general population, currently physicians consume less tobacco and more opioids and sedatives. Research data suggest that physicians consume more alcohol than the general population.

CHARACTERISTICS OF ADDICTED PHYSICIANS Age

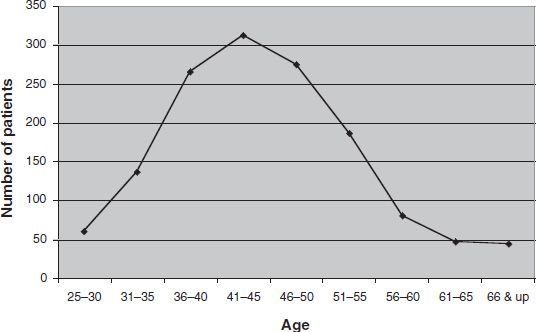

Berry (31) has suggested a bimodal distribution of age at first presentation for treatment; physicians in training and early practice comprise the first wave, and physicians in mid- to late career comprise the second. Talbott et al. (32) reported a decrease in the age of presentation in treatment from 51 to 44 years between 1975 and 1985. In a 2008 analysis of more than 1,400 medical students, residents, and physicians at the same southeastern treatment program, Earley and Weaver (unpublished) noted an age range from 25.3 to 83.7 years, with a median age of 45.8, the ages distributed in a bell curve (Fig. 41-1).

FIGURE 41-1 Distribution of physician age at presentation to treatment.

Gender

Males account for the majority of treated physician addiction cases, with reported ratios approximately 7 to 1 (33). This contrasts with the 3-to-1 male-to-female ratio in the physician population at large (34). Although fewer females than males have drinking problems, female physicians are more likely to report problematic drinking by the end of medical school (5) and are more likely to have alcohol problems later in life than their nonmedical counterparts (35). At intake into one of four PHP programs, female physicians were more likely to be younger and to have medical and psychiatric comorbidity (36). Female physicians were more likely to have past or current suicidal ideation and were more likely to have attempted suicide regardless of whether or not they were under the influence at the time. Wunsch et al. (36) report that female physicians are more likely to abuse sedative/hypnotics than are men. Interestingly, woman physicians are the subject of more severe sanctions by medical boards than their male counterparts (27).

Specialty

Bissell and Jones (35), writing in 1976 about 98 physicians, were among the first to systematically study this cohort. Using a follow-up questionnaire of physicians in Alcoholics Anonymous, she noted that psychiatrists and emergency medicine physicians were overrepresented in Alcoholics Anonymous (overrepresentation defined as a percentage of a cohort that is higher than predicted by the percentage of that cohort in the population of physicians at large). Hughes et al. (17) surveyed 5,426 physicians regarding substance use through an anonymous survey. A self-report of substance abuse or dependence to alcohol or other drugs was highest in psychiatrists and emergency medicine physicians and lowest in surgeons and pediatricians. This question did not break down the substance used or its legality.

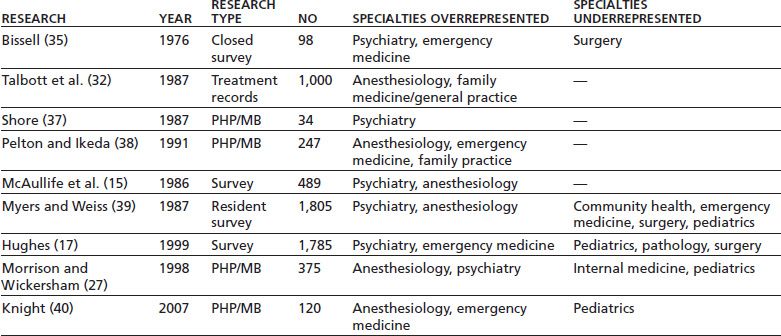

A synopsis of the literature on addiction rates by spe-cialty appears in Table 41-1, which covers multiple authors and modes of analysis. The combined literature looks at the breakdown by specialty from multiple angles (treatment presentation, self-report, and medical board and PHP data); the data consistently validate that psychiatry and emergency medicine physicians have higher rates of substance abuse. Table 41-1 also suggests that family practice physicians might be overrepresented, and pediatricians and pathologists appear to have a lower prevalence of addiction.

TABLE 41-1 REVIEW OF RESEARCH ON ADDICTION RATES BY SPECIALTY

PHP/MB, physician health program or medical board record study.

The problem of addiction in anesthesiologists continues to attract research and debate. Lutsky et al. (16) noted that anesthesiologists were heavier users of marijuana and psychedelics when compared with medicine and surgery physicians but suggested caution in the interpretation of these data owing to age differences between the medicine and surgery cohort and the anesthesiology cohort. Talbott et al. (32) note that anesthesiologists account for 5% of all physicians, yet they account for 13% of all physician-patients in a residential treatment program. In contrast, Hughes et al. (18) noted a low overall rate of substance use in anesthesiology, both in residency and after completing training (17). In their study, Lutsky et al. (16) found that the use of fentanyl (and its relatives) occurred only in anesthesiologists. Hughes et al. (17) noted a trend toward more frequent use of the major opioids, such as fentanyl, in anesthesiologists, but the finding did not reach statistical significance. Propofol use, although infrequent, appears to plague health care professionals who work in settings with high access.

Gold et al. (41) and McAuliffe et al. (42) have recently hypothesized that anesthesiologists may be sensitized to opioids and propofol through the inhalation of picograms of these potent agents in the operating room air. Assays of operating room air detected these agents, especially when taken near the expiration point of the anesthetized patient. This hypothesis rests on an uncertain foundation (the assumption that the quantities of these agents are sufficient to produce sensitization and that the resultant sensitization directly contributes to the etiology of addiction) but does introduce additional avenues of research.

With one significant exception in the data (17), anes-thesiologists appear to be frequent users of highly potent opioids and are strikingly overrepresented in treatment settings. Access to large quantities of these high-potency opioids (and other drugs) in the day-to-day practice of anesthesia is the most likely culprit for the prevalence of anesthesia personnel in treatment settings.

DRUGS ABUSED

Alcohol

Two types of studies are used to assess the types of drugs abused by physicians: anonymous questionnaires (12, 15–21) and self-reports of drugs of choice of physicians as they appear in treatment or monitoring programs (32). Both types of research underscore that alcohol is, as expected, the most frequent primary substance of abuse by physicians, just as it is in the general population.

Nicotine

Tobacco dependence has been suggested as a risk factor for alcohol and other drug dependence in physicians (43) as in the general population (44). Tobacco use in physicians has decreased over time. Vaillant (22) reported that 39% of physicians reporting 10 or more cigarettes per day in 1953, decreasing to 25% in 1968 (22). Nelson et al. reported that smoking among physicians declined from 18.8% in 1976 to 3.3% in 1991 (45). In a 1996 study, Mangus reported 2% of medical school graduates were current smokers (23). From the earlier data, emergency medicine and surgery physicians are twice as likely to smoke as were other physicians (17). Preliminary data from Stuyt et al. (46) strongly correlate the continued use of tobacco with subsequent relapse into other drug or alcohol use, underscoring the relationship of tobacco use with addiction in physicians.

Opioids

Opioids are the second most frequently abused substance by physicians presenting for treatment (47). This finding has been remarkably stable over time, but the type of opioids used continues to change. Hughes et al. (17) differentiate opioid use into the major opioids (morphine, meperidine, fentanyl, and other injectable narcotics) and the minor opioids (hydrocodone, lower dose forms of oxy-codone, codeine, and other oral drugs). Distinguishing in this manner, they reported that family practice and obstetrics and gynecology specialists have a higher probability of abusing minor opioids. When compared with all physicians, the study reports that anesthesiologists were less likely to use minor opioids, with a trend toward an increased use of major opioids. If one assumes that use of major opioids results in a more aggressive manifestation and progression of addiction, this would partly account for the overrepresentation of anesthesiologists over other specialties in physician treatment programs (32). Several authors (17,19,48) posit that exposure to drugs of abuse in the workplace leads to higher abuse of those workplace drugs. This postulate is supported by the frequent abuse of major opioids by anesthesiologists. In a similar manner, family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology physicians are frequent prescribers and use more minor opioids than other specialties (17).

Cocaine

In one study, professions that use cocaine medicinally (ophthalmology, head and neck surgery, plastic surgery, and oto-laryngology) had a (not statistically significant) trend to higher cocaine use (17). Hyde and Wolfe (49) noted that when cocaine is abused by surgery residents, it often comes from hospital sources, but this study is from older literature and does not reflect the current pharmacy controls over this substance.

Benzodiazepines

One hypothesis of substance misuse among physicians suggests that the physicians themselves might more commonly abuse drugs that are used and helpful in a physician’s line of work. Survey-based studies report that psychiatrists have a greater misuse of benzodiazepines; 26.3% report using unsupervised benzodiazepines in the past year, in comparison with 11.4% in other physician groups (17). This high rate of benzodiazepine misuse is reflected in the overrepre-sentation of psychiatrists in treatment.

Propofol

Eighteen percent of anesthesia training programs report cases of propofol abuse (50). The prevalence of propofol abuse in such programs has increased fivefold in the past decade (50). Wischmeyer et al. identified 25 anesthesia personnel with propofol abuse; seven died as a direct result. This study described a positive correlation between hospitals with easy availability and subsequent propofol misuse. High availability was defined as little or no control over drug access within the training hospital. Although common among anesthesiologists in training, this propofol abuse pattern also occurs in physicians (and nurse anesthetists) in practice. In contrast, propofol use in nonmedical personnel is extremely rare; only one such case has been reported (51).

Propofol use has recently gained the national attention after the death of pop star Michael Jackson in 2009. Increasing reports of propofol abuse (52) and research about its addicting qualities have resulted in the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) placing fospropofol (53) under Schedule IV and a proposed Schedule IV for propofol as well (54). As of this writing, propofol remains unscheduled (55).

Illicit Drugs

The most common street drug of abuse among medical residents is marijuana (18). Physicians from all specialties abuse marijuana, with emergency medicine, anesthesiol-ogy, family practice, and psychiatry physicians displaying elevated odds of marijuana abuse over physicians as a whole (17). Cocaine use is more common in emergency medicine physicians, presumably from street sources. Several authors (48,56,57) have postulated that the personality style of these specialties attracts them to these drugs of abuse.

Other Drugs

Physicians are also found to abuse drugs that are not generally available or not recognized as having an abuse potential by the general public. Skipper (58) reported that tramadol was the third most frequent opioid mentioned by physicians (behind hydrocodone and meperidine) “although it was rarely the primary drug of choice” in a study of 595 physicians from two state PHPs over an 8-year period. Moore and Bostwick (59) described two cases of ketamine abuse in anesthesiologists; some professional treatment programs see several ketamine-dependent physicians per year.

RISK FACTORS

The risk for addiction in physicians is an area rich in speculation and poor in research.

Genetics

The strongest predictor of alcohol or drug problems in physicians is the same as in the general population: a family history of alcoholism or drug dependence (5). Of importance in this regard is the work of Moore (43) who observed several genetic and substance use factors in medical students that later correlated with alcohol abuse including non- Jewish ancestry (relative odds [RO] = 3.1), cigarette use of one pack or more per day (RO = 2.6), and regular use of alcohol (RO = 3.6).

Personality

All physician specialties are burdened with common stereotypes, and it has long been tempting to speculate about causal personality factors in the development of physician addiction. At the outset, it must be noted that in the general population, decades of research have failed to support an “addictive personality.” Observed physician personality dynamics may be a consequence or an epiphenomenon to the true etiology of the addictive process. With the preceding caveats, it is still interesting to review published speculations about physician personality types and addiction. Although personality issues may or may not be causative in addiction, they often play an important role in the progression, presentation, and treatment of addiction disorders and therefore are covered below.

McAuliffe et al. (60) noted “sensation seeking” as a personality factor that is correlated with recreational drug use among physicians in training. These authors speculate that such individuals gravitate to specialties such as emergency medicine. Emergency medicine physicians may self-select high-risk or illicit drugs owing to the same personality characteristics that draw them to their specialty. Emergency medicine physicians, as reported by Hughes et al. (17), were twice as likely to use marijuana as other specialties. Their data also suggested cocaine use was higher in this cohort. However, this hypothesis is not supported by data from other specialties also thought to attract sensation-seeking individuals, such as surgery, which is not overrepresented in treatment settings.

Bissell and Jones (35) suggest perfectionist behavior and a high-class ranking are risk factors for addiction. This is supported by the work of Higgins Roche (61), who noted that addicted anesthesiologists are often in the top 10% to 20% of their class. Udel (62) notes that compulsive personality disorder (or traits) is the most common personality diagnosis of physicians presenting for treatment. No data differentiating the occurrence of compulsive traits in addicted or nonaddicted physicians are available. Many consider compulsive traits beneficial in physician training and work. Zeldow (48) and Yufit et al. (56) speculate that the introverted and introspective qualities as well as a drive for an internal locus of control are partially responsible for the drug of choice selection in this population.

Drug Access

O’Connor and Spickard (1) described a subset of physicians who began abusing benzodiazepines and opioids only after receiving prescribing privileges. Drug access may also account for changing drugs of abuse within the opioid class over time. Green et al. (63) in 1976 and Talbott et al. (32) in 1987 reported the predominant opioid abused by physicians at the time was meperidine (Demerol). A more recent (2004) review of the Michigan and Alabama Physicians Health Programs reports hydrocodone as the number 1 opioid abused (40% of all opioid cases), meperidine dropping to 10% of cases (58). The most likely hypothesis for shifts in the drug of choice by physicians over time is the changing prescribing patterns and availability of these drugs in the marketplace.

Biologic Effect of the Drug of Choice

The neurobiologic effects of drugs used by those with an addiction color the characteristics of the addiction disorder itself. Drug-of-choice characteristics also skew the characteristics of the physician-patients arriving in treatment programs. For example, all opioids produce intense tolerance, resulting in histories of ever-increasing doses. Drug hunger drives the progressively tolerant physician to divert increasing quantities of opioids from work and, in doing so, increases the probability of detection. This partially explains why treatment-seeking or treatment-mandated physicians tend to present disproportionately with opioid abuse histories.

Major anesthetic opioids (such as fentanyl) when consumed parenterally produce a rapid downhill course owing to the development of remarkable levels of tolerance. The accelerated course of addiction from the most potent opi-oids can be postulated as contributing to deaths and the high percentage of anesthesiologists seen in physician treatment programs. Collins (3) has suggested that rapid onset (and the resolution of tolerance with brief periods of abstinence) and/or low therapeutic ratio may account for the high mortality rate in propofol-, fentanyl-, sufent-anil-, alfentanil-, and remifentanil-abusing anesthesiolo-gists. Increased awareness along with checks and balances to account for the remaindered volumes of fentanyl used in hospitals may detect diversion more rapidly and save lives of anesthesia personnel (16).

ADDICTION COMORBIDITY

Thought and Mood Disorders

Physicians suffer from a spectrum of emotional and psychiatric problems similar to the general population. However, addicted physicians rarely have comorbid primary schizophrenia and related thought disorders. Although it is unclear whether physicians have higher or lower rates of unipolar depression, physicians who successfully complete suicide are more likely to have a drug abuse problem in their lives, self-prescribed psychoactive substances, a recent alcohol-related problem, a history of emotional problems prior to 18 years of age, and/or a family history of alcohol abuse and/ or mental illness (64). Substance dependence, self-criticism, and dependent personality characteristics are associated with depression in physicians (65). Bipolar disorder (types I and II) may contribute to the intensity of addictive disease in physicians, particularly for drinking during manic intervals (66).

Pain

PHPs are working with an increasing number of physicians with chronic pain and analgesic opioid use, many of whom have become physiologically dependent. In turn, an unknown percentage of those go on to become addicted. Eventual addiction is thought to be more common in patients with pain disorders (67) and, when combined with the 25% of physicians who self-prescribe (15), a perfect storm of high-risk factors emerges. Physicians who have significant pain and addiction disorders pose diagnostic, treatment, and management difficulties for assessors, treatment providers, and the PHPs. Regulatory issues cloud the treatment of addicted physicians with pain: Should a formerly addicted physician on opioid drugs be allowed to practice? Is it logical for state boards to prohibit methadone or buprenorphine maintenance for addiction treatment but permit potent opioids for pain management? These complex questions often result in ideologic or political decisions rather than evidence-based answers. Scientific data on the safety of physicians practicing on opioids, whether addicted or not, are sorely lacking. Insufficient data are available for a definitive decision, but appropriate concern remains (68).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcoholism are closely intertwined (69), and PTSD increases the probability of addiction relapse in PTSD-related contexts (70). However, no studies about the prevalence of PTSD in physicians have been published. Physicians, like anyone else, are not immune from prior trauma histories. Several physician specialties, including emergency medicine physicians, trauma surgeons, and military psychiatrists, treat the immediate and chronic consequences of trauma. Although combat exposure is known to increase the statistical risks of addiction in veterans, no data exist to indicate whether such trauma increases the likelihood of substance abuse disorders in military physicians. Treating trauma can be, in itself, traumatizing to the caregiver.

THEORIES OF ADDICTION AMONG PHYSICIANS

The natural history of addiction is, on the surface, similar in physicians to that of any other drug- or alcohol-dependent person. McAuliffe (57) reports that 27% of medical students and 22% of physicians had family histories of alcohol dependence. Lutsky et al. (16) and Domino et al. (71) put this figure at almost 75%. Moreover, the genetic research literature now supports inherited genetic vulnerabilities for all major classes of addictive drugs.

Clark et al. (21) reported that excessive alcohol consumption in medical students was positively associated with better grades in the first year and a strong tendency toward better scores on Part One of the National Board of Medical Examiners test. Alcohol abuse was found to have no discernible impact on clinical rotations in years 3 and 4 of medical school in this study. This led Clark to speculate that hard-drinking students may be prone to discount warnings and feel invulnerable to the effects of alcohol; their own internal experience does not match cautionary information provided to them during their medical education. This may exacerbate an emerging “us” (doctors) and “them” (patients) view of the world. These findings mirror extensive research by Schuckit, who consistently demonstrated that less intense, early-life responses to alcohol increase the risk for the later development of alcoholism (72,73).

Stress is often cited by the physician-patient as the primary agent that drives self-medication. Stress is an elusive concept; its exact correlation with substance use and addiction is unclear. Physicians report similar levels of stress as other health professionals (74). Physicians in treatment for chemical dependency report that the stress of medical training, when combined with social isolation, provides a fertile soil for the growth of drug consumption (3). Jex (75) suggests that the physician’s unhealthy response to stress is a more important determinant of addiction than the ubiquitous presence of stress itself.

No evidence supports a specific professional personality type as being determinant in addiction. Personality dynamics specific to physicians naturally must play a role in the course of the illness and its treatment (76,77). Vaillant et al. (78) have suggested that physicians commonly experience an emotionally barren childhood. Johnson and Connelly (79), who identified 72% of a 50-physician sample hospitalized for addiction as experiencing parental deprivation in their childhood, echo this postulate. Khantzian (80) eloquently depicts the physician’s efforts at caring for others as a partially successful transformation of the conflict about being cared for themselves and an attempt to correct the barren nature of their parental nurturance. Tillet (76) described this dynamic in helping professionals as a drive to “compulsively give to others what he (she) would like to have for himself (herself).” When this transformation fails, the addiction-prone physician, lacking other methods of self-care, has a propensity to turn to substance use.

Physicians in the act of saving human lives develop a varying degree of omnipotence (4). This omnipotence, when combined with knowledge of the drugs they prescribe, may produce feelings of invulnerability regarding drug or alcohol use. Vaillant (24) has speculated that self-prescribing (related to physician self-sufficiency and false omnipotence) plays a permissive role in the development of addiction in physicians. Physicians’ illusion of mastery over pharmaceuticals keeps them from distinguishing their lack of control over chemical use, opening the door to experimentation and, if continued, a progressive deterioration in their drug use.

Genetic vulnerability and the priming effects of the drug itself remain the most evidence-based etiologies of addiction. Childhood experiences, medical school training about pharmaceuticals, and the life-and-death nature of a physician’s work certainly modify the quality and progression of a nascent addiction problem. Physicians are taught in medical school and residency (and often in their childhood) to appear self-sufficient and in control. This façade of competence establishes the framework for a secretive and duplicitous personality and, once abusing drugs or alcohol, his or her secret garden provides a fertile soil for additional chemical use. Concealment and lying are not qualities that support a mature approach to marriage, life, and work. The illicit and secretive qualities of addiction promulgate additional personality regression.

The physician’s behavior deteriorates first at home, then with friends, and finally surfaces at the workplace. By the time a physician exhibits problems at work, significant familial discord (marital strife, divorce, difficulties with acting out in children) commonly exists. Rarely does the family “turn in” an addicted spouse or other family member (81). Often, hospital staff or a colleague becomes publi-cally worried first. The physician is then confronted at work when an undeniable incident occurs or a series of smaller incidents push colleagues and the hospital medical staff to confront the doctor. An active PHP, especially one that is supportive and confidential, can be very beneficial in reducing the threshold for reporting to punitive agencies and, thus, can promote early detection. Most physicians arrive in treatment with thin scraps of their façade remaining. They exhibit a demeanor of superiority and knowledge, deny any loss of control, and have a need to appear competent, in stark contrast to their crumbling lives.

IDENTIFICATION, INTERVENTION, AND ASSESSMENT

Identification

Physicians present with a broad spectrum of symptom severity, from a physician self-identifying his alcoholism while in couples’ therapy, all the way to an apneic and asystolic physician on the floor of the operating room bathroom. In the past, denial, shame, and fear of reprisal tended to keep the physician from seeking proper help until significant external consequences coalesced (2). In more recent years, the emergence of clinically oriented, supportive, and confidential PHPs has stimulated earlier reporting, by either self- or colleague referral. Physician-patients have often had years of familial and social discord while struggling to maintain acceptable work performance, until this last refuge, too, collapses. Thus, disturbances of social or familial functioning may be more sensitive indicators of early substance dependence in the physician. Unfortunately, the family often protects the alcohol- or drug-dependent “bread winner” physician.

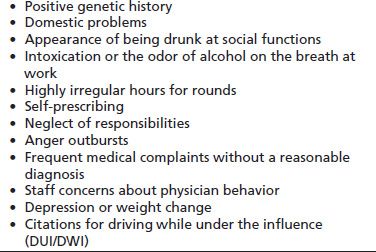

A variety of work-related behaviors can be clues to substance use. O’Connor and Spickard (1) describe conditions and warning signs that can help detect addiction (Table 41-2). Talbott and Wright (81) and Talbott and Benson (128) have independently reported a similar list of behavioral signs of addiction in the physician.

TABLE 41-2 WARNING SIGNS OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE IN PHYSICIANS

Adapted from O’Connor PG and Spickard A. Physician impairment by substance abuse. Med Clin North Am 1997;81(4):1037–1052.

If problems are not addressed early, the doctor’s work quality and attendance often suffer. In contrast, if a physician obtains drugs at work (e.g., samples from a drug closet or drugs diverted from the OR or ICU), he or she displays the opposite behavior—volunteering for additional shifts, arriving early for work, and signing up for more complex (i.e., easier drug access) cases.

Modes of Intervention

Several comprehensive guides to physician intervention have been published (2,82). In recent years, PHPs have become very skilled at directing the physician-patient into treatment without overly aggressive confrontation and ultimatums. Tension involved in the intervention process can be reduced by directing the physician suspected of addictive disease to undergo an evaluation rather than insisting that addiction exists and treatment is indicated. The physician in question is told about existing concerns (often without divulging the source of information) and the importance of resolving said concerns by undergoing a thorough and authoritative evaluation. Ultimately, the goal of intervention is early detection of whatever problem is causing concerns. The immediate goal is to get the physician in question into a “safe harbor,” to undergo appropriate evaluation.

If handled with tact, as is common with experienced PHPs, physicians can usually be “gently coerced” into an evaluation, given the alternative of possible medical board referral and possible legal action. However, some physicians, especially those who have in the past felt assaulted by a legal process or have undergone previous interventions, require additional external pressure to begin the evaluation and/or treatment process. Regardless of the level of encouragement needed to get physician-patients into evaluation, they often arrive with a thinly fabricated story depicting their entry into evaluation or treatment as self-motivated.

Most states have reporting laws (“snitch laws”) that require hospitals and colleagues to report to the state PHP or their state medical board a physician who is suspected of being impaired by alcohol or drugs. Treating physicians must have knowledge of the laws in their state before embarking down the road of caring for physician-patients. In 2001, the Joint Commission pressured hospital organizations to address the wellness of their medical staff through standard MS2.6 (83). This Joint Commission standard has helped formalize a physician health process in most hospitals and formalize the support and intervention network in hospitals. In most states, the PHP is willing to take on or assist the hospital in meeting this standard (84,85). Hospital wellness committees can be effective in early identification and referral of addicted physicians if the process maintains a balance of compassion with a firm directive hand. Wellness committees are distinct in their focus and agenda from a hospital credentialing or executive committee whose primary agenda is managing a hospital’s greater risk management strategy. Therefore, a firewall should be maintained between the wellness and credentialing/executive committees.

If substance dependence is not caught in its early stages, the possibility of impairment arises. Thus, the primary public health goal of PHPs is to diagnose and treat physicians early in the course of their illness. In a study of impairment of all types (not focused solely on substance-induced impairment), Igartua (86) reported that 7% of residents in her survey reported working with an impaired physician supervisor. Impaired supervisory physicians are no longer protected and enabled by their juniors. Reuben and Noble (87) reported that 72% of house officers would report an impaired attending physician.

Assessment

Physicians vary on their need for assessment. Some are quickly identified and agree to cooperate with their treatment needs or at least with an outpatient evaluation. Physicians who are more entrenched in their addiction, who have more complex presentations, or who are frankly resistant need formal and more extensive assessment and a methodical, nonshaming confrontation of their denial complex. In these cases, timely and proper diagnosis is best made by a multidisciplinary evaluation using the guidelines established by the Federation of State PHPs (88). Assessment can be completed at the least intensive level of care that results in a comprehensive view of the patient and his or her family and social system. The examination process must prevent the assessed physician from hiding continued drug use and withdrawal as well as addiction-related interpersonal behaviors. Because of the complexity and comprehensive nature of these evaluations, many evaluators conduct them in a residential or partial hospitalization setting where the physician remains under continuous observation. A comprehensive evaluation is best performed by removing the doctor from his or her work role to a center with expertise and willingness to take on the sometimes laborious and difficult task of physician evaluation. Allowing physicians to self-select an evaluator commonly results in their choosing a friend or colleague or someone who lacks the necessary expertise in the nuances of a physician addiction evaluation. This results in an inadequate or limited evaluation and thus a missed chance at early diagnosis. Therefore, most PHPs have established criteria and maintain a list of competent evaluators.

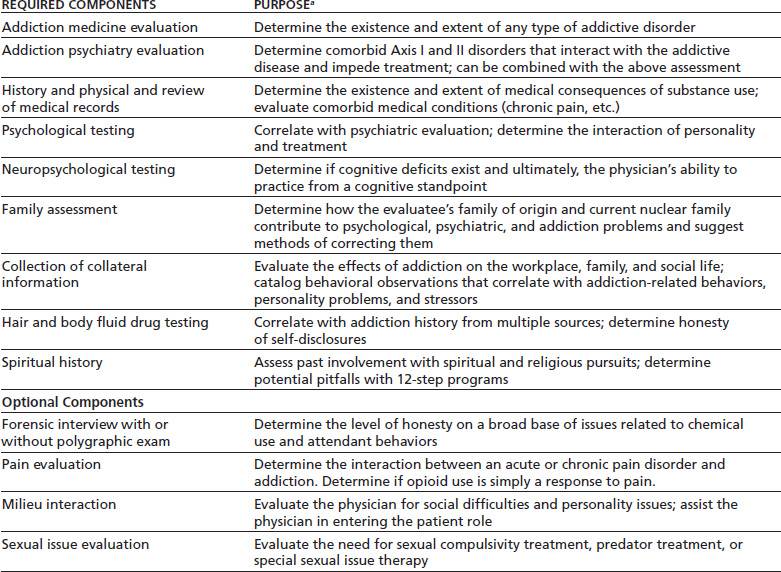

The evaluation should include information from, but should not be carried out by, a current or past therapist, psychiatrist, or other caregiver (9). Many PHPs direct the evaluation to a multidisciplinary team composed of an addiction medicine physician and an addiction psychiatrist and include psychological and neuropsychological testing, family assessment, review of previous medical records, and the collection of collateral information from coworkers, hospital employees, friends, and PHPs themselves. A broad array of information from all available resources is critical to an accurate assessment. Table 41-3 outlines the purpose of each component of a comprehensive physician addiction evaluation.

TABLE 41-3 COMPONENTS OF A SUGGESTED COMPREHENSIVE PHYSICIAN ADDICTION ASSESSMENT

aAll components of the evaluation contribute to determination of whether an addictive disease exists, the level of care needed, and treatment planning for eventual care, if any.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree